Hip dislocation

| Dislocation of hip | |

|---|---|

| |

| X-ray showing a joint dislocation of the left hip. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Hip pain, trouble moving the hip[1] |

| Complications | Avascular necrosis of the hip, arthritis[1] |

| Types | Anterior, posterior[1] |

| Causes | Trauma[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Confirmed by X-rays[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Hip fracture, hip dysplasia[3] |

| Prevention | Seat-belts[1] |

| Treatment | Reduction of the hip carried out under procedural sedation[1] |

| Prognosis | Variable[4] |

| Frequency | Uncommon[5] |

A hip dislocation is a disruption of the joint between the femur and pelvis.[1] Specifically it is when the ball–shaped head of the femur comes out of the cup–shaped acetabulum of the pelvis.[1] Symptoms typically include pain and an inability move the hip.[1] Complications may include avascular necrosis of the hip, injury to the sciatic nerve, or arthritis.[1]

Dislocations are typically due to significant trauma such as a motor vehicle collision or fall from height.[1] Often there are also other associated injuries.[2][6] Diagnosis is generally confirmed by plain X-rays.[2] Hip dislocations can also occur follow a hip replacement or from a developmental abnormality known as hip dysplasia.[7]

Efforts to prevent the condition include wearing a seat-belt.[1] Emergency treatment generally follows advanced trauma life support.[2] This is generally followed by reduction of the hip carried out under procedural sedation.[1] A CT scan is recommended following reduction to rule out complications.[8] Surgery is required if the joint cannot be reduced otherwise.[2] Often a few months are required for healing to occur.[1] [9]

Hip dislocations are uncommon.[5] Males are affected more often than females.[3] Traumatic dislocations occurs most commonly in those 16 to 40 years old.[4] The condition was first described in the medical press in the early 1800s.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The affected leg is virtually immovable by the person, and is usually extremely painful.[10] Dislocations are categorized as either posterior or anterior, based on the location of the head of the femur (see classification above).[11]

Posterior dislocation

Nine out of ten hip dislocations are posterior.[12] The affected limb will be in a position of flexion, adduction, and internally rotated in this case.[13] The knee and the foot will be in towards the middle of the body.[10] A sciatic nerve palsy is present in 8%-20% of cases.[13]

Anterior dislocation

In an anterior dislocation the limb is held by the person in externally rotated with mild flexion and abduction.[14] Femoral nerve palsies can be present, but are uncommon.[13]

Cause

Dislocations of the hip typically take a high degree of force.[2] About 65% of cases are related to motor vehicle collisions, with falls and sports injuries being the cause of many of the rest.[2]

Mechanism

The hip joint includes the articulation of the femoral head (of femur) and the acetabulum of the pelvis. In hip dislocation, the femoral head is dislodged from this socket. Posterior dislocation is the most prevalent, in which the femoral head lies posterior and superior to the acetabulum. This is most common when the femur is adducted and internally rotated. The opposite is true for the shoulder, where the most common dislocation occurs in the anterior and inferior directions.[15] Motor vehicle traffic collisions are responsible for almost all posterior hip dislocations.[4] The posterior side of the hip exhibits primarily hip extension, dealing with the muscles: gluteus maximus, hamstring muscles (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus), and the six deep external rotators (piriformis, obturator externus, obturator internus, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and quadrates femoris).[16]

To actually dislocate a healthy hip, a great amount of force needs to be applied. Falls from a height, such as a ladder, can also generate enough force to dislocate a hip. In older individuals, even a slight fall could cause this type of injury. Wear and tear that the body undergoes throughout the years leads to increased incidents of hip dislocation in the older population.[17]

Several other injuries are also associated with hip dislocation. Fractures in the pelvis and legs, and minor back or head injuries can also occur, along with a hip dislocation, that is caused by a fall or athletic of injury.

Diagnosis

Anterior-posterior (AP) X-rays of the pelvis, AP and lateral views of the femur (knee included) are ordered for diagnosis.[13] The size of the head of the femur is then compared across both sides of the pelvis. The affected femoral head will appear larger if the dislocation is anterior, and smaller if posterior.[14] A CT scan may also be ordered to clarify the fracture pattern.

.png.webp) Hip dislocation

Hip dislocation.jpg.webp) Congenital hip dislocation

Congenital hip dislocation.jpg.webp) Anterior dislocation of the hip

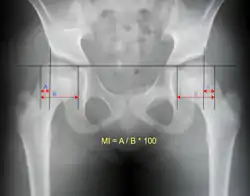

Anterior dislocation of the hip Reimer's migration index can be used to indicate hip dislocation. The migration index (MI) is normally less than 33%.[18]

Reimer's migration index can be used to indicate hip dislocation. The migration index (MI) is normally less than 33%.[18]

Classification

Posterior dislocation

Posterior dislocations with an associated fracture are categorised by the Thompson and Epstein classification system, the Stewart and Milford classification system, and the Pipkin system (when associated with femoral head fractures).[19][14]

Anterior dislocation

There is also a Thompson and Epstein classification system for anterior hip dislocations.[19][14]

Central dislocation

Central dislocation is an outdated term for medial displacement of the femoral head into a displaced acetabular fracture.[14] It is no longer used.

Hip dysplasia

Hip dysplasia is a condition in which a child is born with a hip problem. Hip dysplasia is when the formation of the hip joint is abnormal. The ball at the top of the thighbone which is known as the femoral head is not stable within the socket (which is also known as the acetabulum).

Hip dysplasia is the preferred term because it provides a more accurate description of the spectrum of abnormalities that affect the immature hip.[20] The term "congenital" dislocation is no longer recommended, except for very rare conditions, in which there is a ("teratologic") fixed dislocation location present at birth.[13]

Management

Uncomplicated

The hip should be reduced as quickly as possible to reduce the risk of osteonecrosis of the femoral head.[4] This is done via inline manual traction with procedural sedation and analgesia (PSA) or general anesthesia and muscle relaxation.[14] Fractures of the femoral head and other loose bodies should be determined prior to reduction.

Common closed reduction methods include the Allis method and Stimson method. Once reduction is completed management becomes less urgent and appropriate workup including CT scanning can be completed.[14] Post-reduction, people may begin early crutch-assisted ambulation with weight bearing as tolerated.

Complicated

If the dislocated hip cannot be reduced by manipulation alone, an immediate open (surgical) reduction is necessary. A CT scan or Judet views should be obtained prior to transfer to the surgical suite.[14]

Rehabilitation

Hip dislocation rehabilitation can take anywhere from two to three months, depending on the person. Complications to nearby nerves and blood vessels can sometimes cause loss of blood supply to the bone, also known as osteonecrosis. The protective cartilage on the bone can also be disturbed from this type of injury. For this reason, it is important for people to contact a physician and get treatment immediately following injury.[17]

- The first step to recovering from a hip dislocation is reduction. This refers to putting the bones back into their intended positions. Normally, this is done by a physician while the person is under a sedative. Other times, a surgical procedure is required to reduce the hip bones back into their natural state.[21]

- Next, rest, ice, and take anti-inflammatory medication to reduce swelling at the hip.[21]

- Weight bearing is allowed for the type one posterior dislocation, but should only be done as pain allows and person is comfortable.[21]

- Within 5–7 days of the injury occurrence, people may perform passive range of motion exercises to increase flexibility.[21]

- A walking aid should be used until the person is comfortable with both weight bearing and range of motion.[21]

Exercises

Individuals suffering from hip dislocation should participate in physical therapy and receive professional prescriptive exercises based on their individual abilities, progress, and overall range of motion. The following are some typical recommended exercises used as rehabilitation for hip dislocation. It is important to understand that each individual has different capabilities that can best be assessed by a physical therapist or medical professional, and that these are simply recommendations.[21]

- Bridge- Lie flat on back. Place arms with palms down beside body. Keep feet hip distance apart and bend knees. Slowly lift hips upward. Hold position for three to five seconds. This helps strengthen the glutes and increase stability of the hip joint.[21]

- Supine leg abduction- Lie flat on back. Slowly slide leg away from body and then back in, keeping the knees straight. This exercises the gluteus medius and helps to maintain stability in the hip while walking.[21]

- Side Lying Leg abduction- Lie on one side with one leg on top of the other. Slowly lift the top leg towards the ceiling and then lower it back down slowly.[21]

- Standing Hip abduction- Standing up and holding on to a nearby surface, slowly lift one leg away from the midline of the body and then lower it back to starting position. This is simply a more advanced way to do any of the lying hip abduction exercises, and should be done as the person progresses in rehab.[21]

- Knee raises- While standing and holding onto a chair, slowly lift one leg off the ground and bring it closer to the body while bending the knee. Then lower the leg back down slowly. This helps to strengthen the hip flexor muscles and retain stability in the hip.[21]

- Hip flexion and extensions- Standing, hold on to a nearby chair or surface. Swing one leg forwards away from you, and hold the position for three to five seconds. Then swing the leg slowly backwards and behind your body. Hold for three to five seconds. This exercise helps to increase range of motion, as well as strengthening the hip flexor and hip extensor muscles that control much of the hip joint.[21]

- Adding ankle weights to any exercises can be done as progress is made in rehabilitation.[21]

Epidemiology

16-40 year-old males are responsible for the majority of hip dislocations. These hip dislocations are typically posterior, and a direct result of motor vehicle traffic collisions.[4]

Other animals

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Hip Dislocation". AAOS. June 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Beebe, MJ; Bauer, JM; Mir, HR (July 2016). "Treatment of Hip Dislocations and Associated Injuries: Current State of Care". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 47 (3): 527–49. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2016.02.002. PMID 27241377.

- 1 2 Blankenbaker, Donna G.; Davis, Kirkland W. (2016). Diagnostic Imaging: Musculoskeletal Trauma E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 495. ISBN 9780323442954. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 1967-, Egol, Kenneth A. (2015). Handbook of fractures. Koval, Kenneth J., Zuckerman, Joseph D. (Joseph David), 1952-, Ovid Technologies, Inc. (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health. p. Chapter 27. ISBN 9781451193626. OCLC 960851324.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Hip Dislocation". www.orthobullets.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Clegg, TE; Roberts, CS; Greene, JW; Prather, BA (April 2010). "Hip dislocations--epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes". Injury. 41 (4): 329–34. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.08.007. PMID 19796765.

- ↑ Callaghan, John J.; Rosenberg, Aaron G.; Rubash, Harry E. (2007). The Adult Hip. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1032. ISBN 9780781750929. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Hip Dislocations". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. August 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Clarke, Sonya; Santy-Tomlinson, Julie (2014). Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing: An Evidence-based Approach to Musculoskeletal Care. John Wiley & Sons. p. 292. ISBN 9781118438848. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Hip Dislocation-OrthoInfo - AAOS". orthoinfo.aaos.org. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Goddard, N. J. (August 2000). "Classification of traumatic hip dislocation". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 377 (377): 11–14. doi:10.1097/00003086-200008000-00004. ISSN 0009-921X. PMID 10943180.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Michael (June 2022). "Managing Posterior Hip Dislocations". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 79 (6): 554–559. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.01.027. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Sarwark, John F. Rosemont, Ill.: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010. ISBN 9780892035793. OCLC 706805938.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Browner, Bruce D.; Jupiter, Jesse B.; Krettek, Christian; Anderson, Paul (9 December 2014). Skeletal trauma : basic science, management, and reconstruction. Browner, Bruce D.,, Jupiter, Jesse B.,, Krettek, Christian, 1953-, Anderson, Paul, 1952-, ClinicalKey. (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455776283. OCLC 898159499.

- ↑ Hip Dislocation in Emergency Medicine at eMedicine

- ↑ Floyd, R.T. (2009). Manual of structural kinesiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

- 1 2 "Hip Dislocation-OrthoInfo - AAOS". Orthoinfo.aaos.org. 1 June 2014. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ Pietro PERSIANI; Iakov MOLAYEM; Alessandro CALISTRI; Stefano ROSI; Marco BOVE; Ciro VILLANI (2008). "Hip subluxation and dislocation in cerebral palsy: Outcome of bone surgery in 21 hips" (PDF). Acta Orthop. Belg. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Thompson, Vernon P.; Epstein, Herman C. (1951). "Traumatic Dislocation of the Hip". The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 33 (3): 746–792. doi:10.2106/00004623-195133030-00023.

- ↑ Jackson, Jonathan C.; Runge, Melissa M.; Nye, Nathaniel S. (15 December 2014). "Common Questions About Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip". American Family Physician. 90 (12). ISSN 0002-838X. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hip Dislocation Treatment & Management at eMedicine

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |