Congenital hyperinsulinism

| Congenital hyperinsulinism | |

|---|---|

| Other names | CHI |

| |

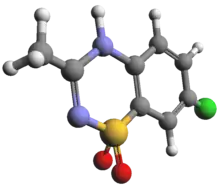

| Insulin (which this condition creates in excess) | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, gastroenterology, endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Hypoglycemia[1] |

| Causes | ABCC8 gene mutations (most common)[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood sample[3] |

| Treatment | Octreotide, and nifedipine [4] |

Congenital hyperinsulinism is a medical term referring to a variety of congenital disorders in which hypoglycemia is caused by excessive insulin secretion.[5][4] Congenital forms of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia can be transient or persistent, mild or severe. These conditions are present at birth and most become apparent in early infancy. Mild cases can be treated by frequent feedings, more severe cases can be controlled by medications that reduce insulin secretion or effects.[5][1]

Signs and symptoms

Hypoglycemia in early infancy can cause jitteriness, lethargy, unresponsiveness, or seizures.[2] The most severe forms may cause macrosomia in utero, producing a large birth weight, often accompanied by abnormality of the pancreas. Milder hypoglycemia in infancy causes hunger every few hours, with increasing jitteriness or lethargy. Milder forms have occasionally been detected by investigation of family members of infants with severe forms, adults with the mildest degrees of congenital hyperinsulinism have a decreased tolerance for prolonged fasting.

Other presentations are:[5][1][4][6]

- Dizziness

- Intellectual disability

- Hypoglycemic coma

- Cardiomegaly

The variable ages of presentations and courses suggest that some forms of congenital hyperinsulinism, especially those involving abnormalities of KATP channel function, can worsen or improve with time. The potential harm from hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia depends on the severity, and duration. Children who have recurrent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in infancy can suffer harm to the brain.[5]

Cause

The cause of congenital hyperinsulinism has been linked to anomalies in nine genes.[7] The diffuse form of this condition is inherited via the autosomal recessive manner (though sometimes in autosomal dominant).[2]

Pathophysiology

In terms of the mechanism of congenital hyperinsulinism one sees that channel trafficking requires KATP channels need the shielding of ER retention signal.E282K prevents the KATP channel surface expression, the C-terminus (SUR1 subunit) is needed in KATP channel mechanism.R1215Q mutations (ABCC8 gene) affect ADP gating which in turn inhibits KATP channel.[7][8]

Diagnostic

In terms of the investigation of congenital hyperinsulinism, valuable diagnostic information is obtained from a blood sample drawn during hypoglycemia, detectable amounts of insulin during hypoglycemia are abnormal and indicate that hyperinsulinism is likely to be the cause.[3] Inappropriately low levels of free fatty acids and ketones provide additional evidence of insulin excess. An additional piece of evidence indicating hyperinsulinism is a usually high requirement for intravenous glucose to maintain adequate glucose levels, the minimum glucose required to maintain a plasma glucose above 70 mg/dl. A GIR above 8 mg/kg/minute in infancy suggests hyperinsulinism. A third form of evidence suggesting hyperinsulinism is a rise of the glucose level after injection of glucagon at the time of the low glucose.[9][10][11][12]

Diagnostic efforts then shift to determining the type- elevated ammonia levels or abnormal organic acids can indicate specific, rare types. Intrauterine growth retardation and other perinatal problems raise the possibility of transience, while large birthweight suggests one of the more persistent conditions. Genetic screening is now available within a useful time frame for some of the specific conditions. It is worthwhile to identify the minority of severe cases with focal forms of hyperinsulinism because these can be completely cured by partial pancreatectomy. A variety of pre-operative diagnostic procedures have been investigated but none has been established as infallibly reliable. Positron emission tomography is becoming the most useful imaging technique.[13]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of congenital hyperinsulinism is consistent with PMM2-CDG, as well as several syndromes. Among other diagnoses, the following are listed:[14]

Types

Congenital hyperinsulinism has two types, diffuse and focal,[5] as indicated below:

- Diffuse hyperinsulinism

- Focal hyperinsulinism

Treatment

_CRUK_287.svg.png.webp)

In terms of treatment, acute hypoglycemia is reversed by raising the blood glucose, but in most forms of congenital hyperinsulinism hypoglycemia recurs and the therapeutic effort is directed toward preventing falls and maintaining a certain glucose level.[5][4] Some of the following measures are often tried:

- Chlorothiazide[4]

- Recombinant IGF-1[5]

- Continuous feeding with formula through a nasogastric tube or gastrostomy[5]

- Dextrose[4]

- Glucocorticoid[5]

- Diazoxide[19]

- Octreotide[19]

- Glucagon[19]

- Nifedipine or other calcium channel blocker[4]

- Pancreatectomy[19]

Corn starch can be used in feeding; unexpected interruptions of continuous feeding regimens can result in sudden hypoglycemia, gastrostomy tube insertion (requires a minor surgical procedure[20]) is used for such feeding. Prolonged glucocorticoid use incurs the many unpleasant side effects of Cushing's syndrome, while diazoxide can cause fluid retention requiring concomitant use of a diuretic, and prolonged use causes hypertrichosis. Diazoxide works by opening the KATP channels of the beta cells. Octreotide must be given by injection several times a day or a subcutaneous pump must be inserted every few days, octreotide can cause abdominal discomfort and responsiveness to octreotide often wanes over time. Glucagon requires continuous intravenous infusion, and has a very short half-life.[4][5][21]

Nifedipine is effective only in a minority, and dose is often limited by hypotension. Pancreatectomy (removal of a portion or nearly all of the pancreas) is usually a treatment of last resort when the less-drastic medical measures fail to provide prolonged normal blood sugar levels. For some time, the most common surgical procedure was removal of almost all of the pancreas; this cured some infants but not all. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus commonly develops, though in many cases it occurs many years after the pancreatectomy. Later it was discovered that a sizeable minority of cases of mutations were focal, involving overproduction of insulin by only a portion of the pancreas. These cases can be cured by removing much less of the pancreas, resulting in excellent outcomes with fewer long-term problems.[4][5][21]

History

This condition has been referred to by a variety of names in the past 50 years; nesidioblastosis and islet cell adenomatosis were favored in the 1970s, beta cell dysregulation syndrome or dysmaturation syndrome in the 1980s, and persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (PHHI) in the 1990s.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Familial hyperinsulinism | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center(GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Reference, Genetics Home. "congenital hyperinsulinism". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- 1 2 Hussain, K. (August 2005). "Congenital hyperinsulinism". Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 10 (4): 369–376. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2005.03.001. PMID 15916932. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Congenital Hyperinsulinism: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2016-07-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Glaser, Benjamin (1 January 1993). "Familial Hyperinsulinism". GeneReviews. Retrieved 9 October 2016.update 2013

- ↑ G.P, TALWAR (2016). TEXTBOOK OF BIOCHEMISTRY, BIOTECHNOLOGY, ALLIED AND MOLECULAR MEDICINE. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 240. ISBN 9788120351257. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- 1 2 Rahman, Sofia A.; Nessa, Azizun; Hussain, Khalid (1 April 2015). "Molecular mechanisms of congenital hyperinsulinism". Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 54 (2): R119–R129. doi:10.1530/JME-15-0016. ISSN 0952-5041. PMID 25733449.

- ↑ James, C.; Kapoor, R. R.; Ismail, D.; Hussain, K. (1 May 2009). "The genetic basis of congenital hyperinsulinism". Journal of Medical Genetics. 46 (5): 289–299. doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.064337. ISSN 1468-6244. PMID 19254908. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ↑ Arnoux, Jean-Baptiste; Verkarre, Virginie; Saint-Martin, Cécile; Montravers, Françoise; Brassier, Anaïs; Valayannopoulos, Vassili; Brunelle, Francis; Fournet, Jean-Christophe; Robert, Jean-Jacques; Aigrain, Yves; Bellanné-Chantelot, Christine; de Lonlay, Pascale (1 January 2011). "Congenital hyperinsulinism: current trends in diagnosis and therapy". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 6: 63. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-63. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 3199232. PMID 21967988.

- ↑ "Blood Glucose Monitoring - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Cloherty, John P.; Eichenwald, Eric C.; Stark, Ann R. (2008). Manual of Neonatal Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 546. ISBN 9780781769846. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ↑ Sprague, Jennifer E.; Arbeláez, Ana María (2017-01-27). "Glucose Counterregulatory Responses to Hypoglycemia". Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews. 9 (1): 463–475. ISSN 1565-4753. PMC 3755377. PMID 22783644.

- ↑ Yang, Jigang; Hao, Ruirui; Zhu, Xiaohua (April 2013). "Diagnostic role of 18F-dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography in patients with congenital hyperinsulinism: a meta-analysis". Nuclear Medicine Communications. 34 (4): 347–353. doi:10.1097/MNM.0b013e32835e6ac6. ISSN 1473-5628. PMID 23376859. S2CID 30804790.

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Congenital isolated hyperinsulinism". www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 602485 - HYPERINSULINEMIC HYPOGLYCEMIA, FAMILIAL, 3; HHF3". omim.org. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 606762 - HYPERINSULINEMIC HYPOGLYCEMIA, FAMILIAL, 6; HHF6". omim.org. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 256450 - HYPERINSULINEMIC HYPOGLYCEMIA, FAMILIAL, 1; HHF1". omim.org. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 601820 - HYPERINSULINEMIC HYPOGLYCEMIA, FAMILIAL, 2; HHF2". omim.org. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- 1 2 3 4 Yorifuji, Tohru (28 November 2016). "Congenital hyperinsulinism: current status and future perspectives". Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 19 (2): 57–68. doi:10.6065/apem.2014.19.2.57. ISSN 2287-1012. PMC 4114053. PMID 25077087.

- ↑ "Feeding tube insertion - gastrostomy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- 1 2 Welters, Alena; Lerch, Christian; Kummer, Sebastian; Marquard, Jan; Salgin, Burak; Mayatepek, Ertan; Meissner, Thomas (1 January 2015). "Long-term medical treatment in congenital hyperinsulinism: a descriptive analysis in a large cohort of patients from different clinical centers". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 10: 150. doi:10.1186/s13023-015-0367-x. ISSN 1750-1172. PMC 4660626. PMID 26608306.

Further reading

- Hoyme, Louanne Hudgins; Toriello, Helga V.; Enns, Gregory M.; Hoyme, H. Eugene (2014). Signs and symptoms of genetic disease : a handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199930975.

- Hertz, David E., ed. (2005). Care of the newborn a handbook for primary care. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781755856.