Intraosseous infusion

| Intraosseous infusion | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Intraosseous vascular access | |

| |

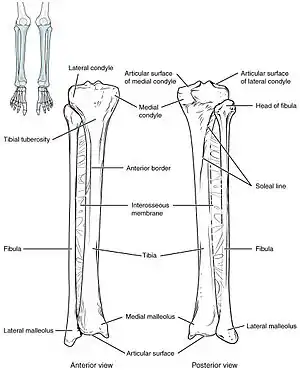

| The tibia IO insertion sites are just below the tibial tuberosity and just above the medial malleolus.[1] | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Indications | Requirement for immediate vascular access[1] |

| Contraindications | Cellulitis or fracture at the site[1] |

| Steps | 1) Sterilize +/- freeze the area 2) Push the needle through the skin until bone is contacted 3) Activate the drill and apply downwards pressure 4) Remove the needle stylet 5) Aspirate marrow, give 2% lidocaine, and than flush[2][1] |

| Success | Stable needle, aspiration of bone marrow, abile to flush normal saline[1] |

| Complications | Fracture, osteomyelitis[1] |

Intraosseous infusion (IO) is an injection through a specialized needle into the marrow of a bone.[1] It is used to give fluids and medication when intravenous access is not easily or rapidly available.[3] It is generally faster than intravenous access, with evidence that it can be placed in under 20 seconds.[1] Blood tests may also be run from an IO sample.[1]

Preparation involve sterilizing the area and potentially using local anesthesia.[1] When using the drill, the first step is to push the needle through the skin perpendicular to the bone until bone is contacted.[2] At this point the drill is activated with some downwards pressure.[2] In adults the proximal tibia and humeral head are most commonly used, while in babies the distal femur and proximal tibia are most commonly used.[1] The site for the proximal tibia is a finger width below the tibial tuberosity and a bit to the inside.[1]

Signs of success include a stable needle, ability to aspirate bone marrow, and the ability to flush normal saline (NS).[1] To reduce injection pain, place 20 mg of 2% lidocaine in an adult before flushing with 10 ml if NS.[1] The needle is then stabilized.[1] Any medication that can be given intravenously (IV) can be given IO, including contrast agents.[1] The device can be used for up to 24 hours.[1] The procedure was developed in the 1920s to 1940s.[1][3]

Medical uses

An IO infusion can be used on an adult or a child when traditional methods of vascular access are difficult or otherwise cause unwanted delayed management of the administration of medications.

Although intravascular access is still the preferred method for medication delivery in the prehospital area, IO access for adults has become more common. As of 2010, the American Heart Association no longer recommends using the endotracheal tube for resuscitation drugs, except as a last resort when IV or IO access cannot be gained.[4] ET absorption of medications is poor and optimal drug dosings are unknown. The IO is becoming more common in civilian and military based pre-hospital emergency medical services (EMS) systems globally.[5]

Intraosseous access has roughly the same absorption rate as IV access, and allows for fluid resuscitation. For example, sodium bicarbonate can be administered IO during a cardiac arrest when IV access is unavailable.[6] High flow rates are attainable with an IO infusion, up to 125 milliliters per minute. This high rate of flow is achieved using a pressure bag to administer the infusion directly into the bone. Large volume IO infusions are known to be painful. 1% lidocaine is used to ease the pain associated with large volume IO infusions in conscious patients.[7]

Contraindications

Intraosseous infusions have several contraindications, including sites that have known or suspected fracture, appear to be infected, or where the skin is burned. Medical conditions that might also preclude the use of intraosseous infusion include osteopenia, osteopetrosis, and osteogenesis imperfecta as fractures are more likely to occur.[6] The procedure also only allows for one attempt per bone, meaning another route of infusion must be secured, or a different bone chosen.[6]

Technique

The needle is injected through the bone's hard cortex and into the soft marrow interior which allows immediate access to the vascular system. The IO needle is positioned at a 90 degree angle to the injection site, and the needle is advanced through manual traction, impact driven force, or power driven.[6] Each IO device has different designated insertion locations. The most common site of insertion is the antero-medial aspect of the upper, proximal tibia as it lies just under the skin and is easily located. This is on the upper and inner portion of the tibia. Other insertion sites include the anterior aspect of the femur, the superior iliac crest, proximal humerus, proximal tibia, distal tibia, sternum (manubrium).[8]

Steps

These are the steps for the EZ-IO.[1] Other methods involve a slightly different technique.[1]

- Sterilize and potentially freeze the area[2][1]

- Push the needle through the skin until bone is contacted[2]

- Activate the drill and apply downwards pressure[2]

- Remove the needle stylet[2]

- Aspirate marrow, give 2% lidocaine, and than flush[2]

- IO placement in the distal tibia

- IO placement in the proximal tibia

- IO placement in the proximal humerus

Devices

The automatic intra-osseous devices allow quick and safe access to the person's vascular system for fluid and medications. There are several IO devices, categorized by their mechanism of action:

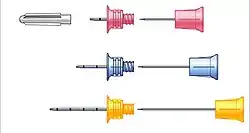

- Electric drill: EZ-IO By Arrow Teleflex.

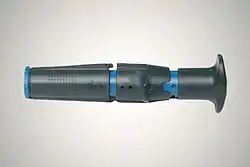

- Spring Loaded: BIG Bone Injection Gun and NIO

- Manual: Fast 1, Fast Combat and Fast Responder, Cook IO Needle and The Janshidi 15G

There have been several studies comparing the EZ-IO and the BIG.[9][10][11] Another paper compared the EZ-IO with the Cook IO needle.[12]

EZ-IO drill

EZ-IO drill Different needle sizes for the EZ-IO

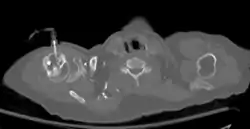

Different needle sizes for the EZ-IO Axial CT with left humeral head EZ IO infusion of contrast.

Axial CT with left humeral head EZ IO infusion of contrast. BIG IO devices

BIG IO devices NIO IO device

NIO IO device

Post-procedure

The IO site can be used for 24 hours and should be removed as soon as intravenous access has been gained. Prolonged use of an IO site, lasting longer than 24 hours, is associated with osteomyelitis (an infection in the bone).[7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Dornhofer, P; Kellar, JZ (January 2021). "Intraosseous Vascular Access". PMID 32119260.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Roberts and Hedges' clinical procedures in emergency medicine and acute care (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. 2019. p. 472. ISBN 9780323547949.

- 1 2 Petitpas, F; Guenezan, J; Vendeuvre, T; Scepi, M; Oriot, D; Mimoz, O (14 April 2016). "Use of intra-osseous access in adults: a systematic review". Critical care (London, England). 20: 102. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1277-6. PMID 27075364.

- ↑ Neumar, Robert W.; Otto, Charles W.; Link, Mark S.; Kronick, Steven L.; Shuster, Michael; Callaway, Clifton W.; Kudenchuk, Peter J.; Ornato, Joseph P.; McNally, Bryan (2010-11-02). "Part 8: Adult Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support". Circulation. 122 (18 suppl 3): S729–S767. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 20956224.

- ↑ Paxton, James H.; Knuth, Thomas E.; Klausner, Howard A. (2009). "Proximal Humerus Intraosseous Infusion: A Preferred Emergency Venous Access". Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care. 67 (3): 606–611. doi:10.1097/ta.0b013e3181b16f42. PMID 19741408. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Luck, Raemma P.; Haines, Christopher; Mull, Colette C. (2010). "Intraosseous Access". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 39 (4): 468–475. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.04.054. PMID 19545966.

- 1 2 Day, Michael W. (April 2011). "Intraosseous Devises for Intravascular Access in Adult Trauma Patients". Critical Care Nurse. 31 (2): 76–89. doi:10.4037/ccn2011615. PMID 21459867 – via EBSCO Host.

- ↑ Dubick, M. A.; Holcomb, J. B. (2000-07-01). "A review of intraosseous vascular access: current status and military application". Military Medicine. 165 (7): 552–559. doi:10.1093/milmed/165.7.552. ISSN 0026-4075. PMID 10920658.

- ↑ Demir OF, Aydin K, Akay H, Erbil B, Karcioglu O, Gulalp B (April 2016). "Comparison of two intraosseous devices in adult patients in the emergency setting: a pilot study". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 23 (2): 137–142. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000187. PMID 25075979. S2CID 21645057.

- ↑ Leidel BA, Kirchhoff C, Braunstein V, Bogner V, Biberthaler P, Kanz KG (August 2010). "Comparison of two intraosseous access devices in adult patients under resuscitation in the emergency department: A prospective, randomized study". Resuscitation. 81 (8): 994–9. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.03.038. PMID 20434823.

- ↑ Shavit I, Hoffmann Y, Galbraith R, Waisman Y (September 2009). "Comparison of two mechanical intraosseous infusion devices: a pilot, randomized crossover trial". Resuscitation. 80 (9): 1029–33. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.05.026. PMID 19586701.

- ↑ Brenner T, Bernhard M, Helm M, et al. (September 2008). "Comparison of two intraosseous infusion systems for adult emergency medical use". Resuscitation. 78 (3): 314–9. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.04.004. PMID 18573590.

External links

- MeSH E05.300.510.560

| External resources |

|---|

-solution.jpg.webp)