Biotechnology

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

|

|

Biotechnology is "the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services."[1] The term biotechnology was first used by Karl Ereky in 1919, meaning the production of products from raw materials with the aid of living organisms.

Definition

The concept of biotechnology encompasses a wide range of procedures for modifying living organisms according to human purposes, going back to domestication of animals, cultivation of the plants, and "improvements" to these through breeding programs that employ artificial selection and hybridization. Modern usage also includes genetic engineering as well as cell and tissue culture technologies. The American Chemical Society defines biotechnology as the application of biological organisms, systems, or processes by various industries to learning about the science of life and the improvement of the value of materials and organisms such as pharmaceuticals, crops, and livestock.[2] Per the European Federation of Biotechnology, biotechnology is the integration of natural science and organisms, cells, parts thereof, and molecular analogues for products and services.[3] Biotechnology is based on the basic biological sciences (e.g., molecular biology, biochemistry, cell biology, embryology, genetics, microbiology) and conversely provides methods to support and perform basic research in biology.

Biotechnology is the research and development in the laboratory using bioinformatics for exploration, extraction, exploitation, and production from any living organisms and any source of biomass by means of biochemical engineering where high value-added products could be planned (reproduced by biosynthesis, for example), forecasted, formulated, developed, manufactured, and marketed for the purpose of sustainable operations (for the return from bottomless initial investment on R & D) and gaining durable patents rights (for exclusives rights for sales, and prior to this to receive national and international approval from the results on animal experiment and human experiment, especially on the pharmaceutical branch of biotechnology to prevent any undetected side-effects or safety concerns by using the products).[4][5][6] The utilization of biological processes, organisms or systems to produce products that are anticipated to improve human lives is termed biotechnology.[7]

By contrast, bioengineering is generally thought of as a related field that more heavily emphasizes higher systems approaches (not necessarily the altering or using of biological materials directly) for interfacing with and utilizing living things. Bioengineering is the application of the principles of engineering and natural sciences to tissues, cells, and molecules. This can be considered as the use of knowledge from working with and manipulating biology to achieve a result that can improve functions in plants and animals.[8] Relatedly, biomedical engineering is an overlapping field that often draws upon and applies biotechnology (by various definitions), especially in certain sub-fields of biomedical or chemical engineering such as tissue engineering, biopharmaceutical engineering, and genetic engineering.

History

Although not normally what first comes to mind, many forms of human-derived agriculture clearly fit the broad definition of "'utilizing a biotechnological system to make products". Indeed, the cultivation of plants may be viewed as the earliest biotechnological enterprise.

Agriculture has been theorized to have become the dominant way of producing food since the Neolithic Revolution. Through early biotechnology, the earliest farmers selected and bred the best-suited crops, having the highest yields, to produce enough food to support a growing population. As crops and fields became increasingly large and difficult to maintain, it was discovered that specific organisms and their by-products could effectively fertilize, restore nitrogen, and control pests. Throughout the history of agriculture, farmers have inadvertently altered the genetics of their crops through introducing them to new environments and breeding them with other plants — one of the first forms of biotechnology.

These processes also were included in early fermentation of beer.[9] These processes were introduced in early Mesopotamia, Egypt, China and India, and still use the same basic biological methods. In brewing, malted grains (containing enzymes) convert starch from grains into sugar and then adding specific yeasts to produce beer. In this process, carbohydrates in the grains broke down into alcohols, such as ethanol. Later, other cultures produced the process of lactic acid fermentation, which produced other preserved foods, such as soy sauce. Fermentation was also used in this time period to produce leavened bread. Although the process of fermentation was not fully understood until Louis Pasteur's work in 1857, it is still the first use of biotechnology to convert a food source into another form.

Before the time of Charles Darwin's work and life, animal and plant scientists had already used selective breeding. Darwin added to that body of work with his scientific observations about the ability of science to change species. These accounts contributed to Darwin's theory of natural selection.[10]

For thousands of years, humans have used selective breeding to improve the production of crops and livestock to use them for food. In selective breeding, organisms with desirable characteristics are mated to produce offspring with the same characteristics. For example, this technique was used with corn to produce the largest and sweetest crops.[11]

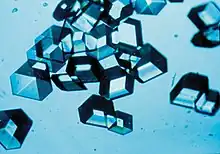

In the early twentieth century scientists gained a greater understanding of microbiology and explored ways of manufacturing specific products. In 1917, Chaim Weizmann first used a pure microbiological culture in an industrial process, that of manufacturing corn starch using Clostridium acetobutylicum, to produce acetone, which the United Kingdom desperately needed to manufacture explosives during World War I.[12]

Biotechnology has also led to the development of antibiotics. In 1928, Alexander Fleming discovered the mold Penicillium. His work led to the purification of the antibiotic compound formed by the mold by Howard Florey, Ernst Boris Chain and Norman Heatley – to form what we today know as penicillin. In 1940, penicillin became available for medicinal use to treat bacterial infections in humans.[11]

The field of modern biotechnology is generally thought of as having been born in 1971 when Paul Berg's (Stanford) experiments in gene splicing had early success. Herbert W. Boyer (Univ. Calif. at San Francisco) and Stanley N. Cohen (Stanford) significantly advanced the new technology in 1972 by transferring genetic material into a bacterium, such that the imported material would be reproduced. The commercial viability of a biotechnology industry was significantly expanded on June 16, 1980, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that a genetically modified microorganism could be patented in the case of Diamond v. Chakrabarty.[13] Indian-born Ananda Chakrabarty, working for General Electric, had modified a bacterium (of the genus Pseudomonas) capable of breaking down crude oil, which he proposed to use in treating oil spills. (Chakrabarty's work did not involve gene manipulation but rather the transfer of entire organelles between strains of the Pseudomonas bacterium.

The MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor) was invented by Mohamed M. Atalla and Dawon Kahng in 1959.[14] Two years later, Leland C. Clark and Champ Lyons invented the first biosensor in 1962.[15][16] Biosensor MOSFETs were later developed, and they have since been widely used to measure physical, chemical, biological and environmental parameters.[17] The first BioFET was the ion-sensitive field-effect transistor (ISFET), invented by Piet Bergveld in 1970.[18][19] It is a special type of MOSFET,[17] where the metal gate is replaced by an ion-sensitive membrane, electrolyte solution and reference electrode.[20] The ISFET is widely used in biomedical applications, such as the detection of DNA hybridization, biomarker detection from blood, antibody detection, glucose measurement, pH sensing, and genetic technology.[20]

By the mid-1980s, other BioFETs had been developed, including the gas sensor FET (GASFET), pressure sensor FET (PRESSFET), chemical field-effect transistor (ChemFET), reference ISFET (REFET), enzyme-modified FET (ENFET) and immunologically modified FET (IMFET).[17] By the early 2000s, BioFETs such as the DNA field-effect transistor (DNAFET), gene-modified FET (GenFET) and cell-potential BioFET (CPFET) had been developed.[20]

A factor influencing the biotechnology sector's success is improved intellectual property rights legislation—and enforcement—worldwide, as well as strengthened demand for medical and pharmaceutical products to cope with an ageing, and ailing, U.S. population.[21]

Rising demand for biofuels is expected to be good news for the biotechnology sector, with the Department of Energy estimating ethanol usage could reduce U.S. petroleum-derived fuel consumption by up to 30% by 2030. The biotechnology sector has allowed the U.S. farming industry to rapidly increase its supply of corn and soybeans—the main inputs into biofuels—by developing genetically modified seeds that resist pests and drought. By increasing farm productivity, biotechnology boosts biofuel production.[22]

Examples

Biotechnology has applications in four major industrial areas, including health care (medical), crop production and agriculture, non-food (industrial) uses of crops and other products (e.g. biodegradable plastics, vegetable oil, biofuels), and environmental uses.

For example, one application of biotechnology is the directed use of microorganisms for the manufacture of organic products (examples include beer and milk products). Another example is using naturally present bacteria by the mining industry in bioleaching. Biotechnology is also used to recycle, treat waste, clean up sites contaminated by industrial activities (bioremediation), and also to produce biological weapons.

A series of derived terms have been coined to identify several branches of biotechnology, for example:

- Bioinformatics (also called "gold biotechnology") is an interdisciplinary field that addresses biological problems using computational techniques, and makes the rapid organization as well as analysis of biological data possible. The field may also be referred to as computational biology, and can be defined as, "conceptualizing biology in terms of molecules and then applying informatics techniques to understand and organize the information associated with these molecules, on a large scale."[23] Bioinformatics plays a key role in various areas, such as functional genomics, structural genomics, and proteomics, and forms a key component in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical sector.[24]

- Blue biotechnology is based on the exploitation of sea resources to create products and industrial applications.[25] This branch of biotechnology is the most used for the industries of refining and combustion principally on the production of bio-oils with photosynthetic micro-algae.[25][26]

- Green biotechnology is biotechnology applied to agricultural processes. An example would be the selection and domestication of plants via micropropagation. Another example is the designing of transgenic plants to grow under specific environments in the presence (or absence) of chemicals. One hope is that green biotechnology might produce more environmentally friendly solutions than traditional industrial agriculture. An example of this is the engineering of a plant to express a pesticide, thereby ending the need of external application of pesticides. An example of this would be Bt corn. Whether or not green biotechnology products such as this are ultimately more environmentally friendly is a topic of considerable debate.[25] It is commonly considered as the next phase of green revolution, which can be seen as a platform to eradicate world hunger by using technologies which enable the production of more fertile and resistant, towards biotic and abiotic stress, plants and ensures application of environmentally friendly fertilizers and the use of biopesticides, it is mainly focused on the development of agriculture.[25] On the other hand, some of the uses of green biotechnology involve microorganisms to clean and reduce waste.[27][25]

- Red biotechnology is the use of biotechnology in the medical and pharmaceutical industries, and health preservation.[25] This branch involves the production of vaccines and antibiotics, regenerative therapies, creation of artificial organs and new diagnostics of diseases.[25] As well as the development of hormones, stem cells, antibodies, siRNA and diagnostic tests.[25]

- White biotechnology, also known as industrial biotechnology, is biotechnology applied to industrial processes. An example is the designing of an organism to produce a useful chemical. Another example is the using of enzymes as industrial catalysts to either produce valuable chemicals or destroy hazardous/polluting chemicals. White biotechnology tends to consume less in resources than traditional processes used to produce industrial goods.[28][29]

- "Yellow biotechnology" refers to the use of biotechnology in food production (food industry), for example in making wine (winemaking), cheese (cheesemaking), and beer (brewing) by fermentation.[25] It has also been used to refer to biotechnology applied to insects. This includes biotechnology-based approaches for the control of harmful insects, the characterisation and utilisation of active ingredients or genes of insects for research, or application in agriculture and medicine and various other approaches.[30]

- Gray biotechnology is dedicated to environmental applications, and focused on the maintenance of biodiversity and the remotion of pollutants.[25]

- Brown biotechnology is related to the management of arid lands and deserts. One application is the creation of enhanced seeds that resist extreme environmental conditions of arid regions, which is related to the innovation, creation of agriculture techniques and management of resources.[25]

- Violet biotechnology is related to law, ethical and philosophical issues around biotechnology.[25]

- Dark biotechnology is the color associated with bioterrorism or biological weapons and biowarfare which uses microorganisms, and toxins to cause diseases and death in humans, livestock and crops.[31][25]

Medicine

In medicine, modern biotechnology has many applications in areas such as pharmaceutical drug discoveries and production, pharmacogenomics, and genetic testing (or genetic screening).

Pharmacogenomics (a combination of pharmacology and genomics) is the technology that analyses how genetic makeup affects an individual's response to drugs.[32] Researchers in the field investigate the influence of genetic variation on drug responses in patients by correlating gene expression or single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a drug's efficacy or toxicity.[33] The purpose of pharmacogenomics is to develop rational means to optimize drug therapy, with respect to the patients' genotype, to ensure maximum efficacy with minimal adverse effects.[34] Such approaches promise the advent of "personalized medicine"; in which drugs and drug combinations are optimized for each individual's unique genetic makeup.[35][36]

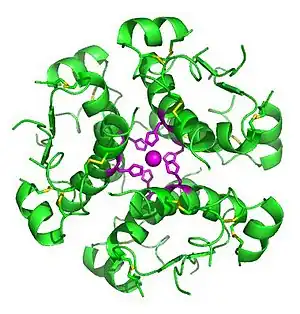

Biotechnology has contributed to the discovery and manufacturing of traditional small molecule pharmaceutical drugs as well as drugs that are the product of biotechnology – biopharmaceutics. Modern biotechnology can be used to manufacture existing medicines relatively easily and cheaply. The first genetically engineered products were medicines designed to treat human diseases. To cite one example, in 1978 Genentech developed synthetic humanized insulin by joining its gene with a plasmid vector inserted into the bacterium Escherichia coli. Insulin, widely used for the treatment of diabetes, was previously extracted from the pancreas of abattoir animals (cattle or pigs). The genetically engineered bacteria are able to produce large quantities of synthetic human insulin at relatively low cost.[37][38] Biotechnology has also enabled emerging therapeutics like gene therapy. The application of biotechnology to basic science (for example through the Human Genome Project) has also dramatically improved our understanding of biology and as our scientific knowledge of normal and disease biology has increased, our ability to develop new medicines to treat previously untreatable diseases has increased as well.[38]

Genetic testing allows the genetic diagnosis of vulnerabilities to inherited diseases, and can also be used to determine a child's parentage (genetic mother and father) or in general a person's ancestry. In addition to studying chromosomes to the level of individual genes, genetic testing in a broader sense includes biochemical tests for the possible presence of genetic diseases, or mutant forms of genes associated with increased risk of developing genetic disorders. Genetic testing identifies changes in chromosomes, genes, or proteins.[39] Most of the time, testing is used to find changes that are associated with inherited disorders. The results of a genetic test can confirm or rule out a suspected genetic condition or help determine a person's chance of developing or passing on a genetic disorder. As of 2011 several hundred genetic tests were in use.[40][41] Since genetic testing may open up ethical or psychological problems, genetic testing is often accompanied by genetic counseling.

Agriculture

Genetically modified crops ("GM crops", or "biotech crops") are plants used in agriculture, the DNA of which has been modified with genetic engineering techniques. In most cases, the main aim is to introduce a new trait that does not occur naturally in the species. Biotechnology firms can contribute to future food security by improving the nutrition and viability of urban agriculture. Furthermore, the protection of intellectual property rights encourages private sector investment in agrobiotechnology.

Examples in food crops include resistance to certain pests,[42] diseases,[43] stressful environmental conditions,[44] resistance to chemical treatments (e.g. resistance to a herbicide[45]), reduction of spoilage,[46] or improving the nutrient profile of the crop.[47] Examples in non-food crops include production of pharmaceutical agents,[48] biofuels,[49] and other industrially useful goods,[50] as well as for bioremediation.[51][52]

Farmers have widely adopted GM technology. Between 1996 and 2011, the total surface area of land cultivated with GM crops had increased by a factor of 94, from 17,000 square kilometers (4,200,000 acres) to 1,600,000 km2 (395 million acres).[53] 10% of the world's crop lands were planted with GM crops in 2010.[53] As of 2011, 11 different transgenic crops were grown commercially on 395 million acres (160 million hectares) in 29 countries such as the US, Brazil, Argentina, India, Canada, China, Paraguay, Pakistan, South Africa, Uruguay, Bolivia, Australia, Philippines, Myanmar, Burkina Faso, Mexico and Spain.[53]

Genetically modified foods are foods produced from organisms that have had specific changes introduced into their DNA with the methods of genetic engineering. These techniques have allowed for the introduction of new crop traits as well as a far greater control over a food's genetic structure than previously afforded by methods such as selective breeding and mutation breeding.[54] Commercial sale of genetically modified foods began in 1994, when Calgene first marketed its Flavr Savr delayed ripening tomato.[55] To date most genetic modification of foods have primarily focused on cash crops in high demand by farmers such as soybean, corn, canola, and cotton seed oil. These have been engineered for resistance to pathogens and herbicides and better nutrient profiles. GM livestock have also been experimentally developed; in November 2013 none were available on the market,[56] but in 2015 the FDA approved the first GM salmon for commercial production and consumption.[57]

There is a scientific consensus[58][59][60][61] that currently available food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food,[62][63][64][65][66] but that each GM food needs to be tested on a case-by-case basis before introduction.[67][68][69] Nonetheless, members of the public are much less likely than scientists to perceive GM foods as safe.[70][71][72][73] The legal and regulatory status of GM foods varies by country, with some nations banning or restricting them, and others permitting them with widely differing degrees of regulation.[74][75][76][77]

GM crops also provide a number of ecological benefits, if not used in excess.[78] However, opponents have objected to GM crops per se on several grounds, including environmental concerns, whether food produced from GM crops is safe, whether GM crops are needed to address the world's food needs, and economic concerns raised by the fact these organisms are subject to intellectual property law.

Industrial

Industrial biotechnology (known mainly in Europe as white biotechnology) is the application of biotechnology for industrial purposes, including industrial fermentation. It includes the practice of using cells such as microorganisms, or components of cells like enzymes, to generate industrially useful products in sectors such as chemicals, food and feed, detergents, paper and pulp, textiles and biofuels.[79] In the current decades, significant progress has been done in creating genetically modified organisms (GMOs) that enhance the diversity of applications and economical viability of industrial biotechnology. By using renewable raw materials to produce a variety of chemicals and fuels, industrial biotechnology is actively advancing towards lowering greenhouse gas emissions and moving away from a petrochemical-based economy.[80]

Synthetic biology is considered one of the essential cornerstones in industrial biotechnology due to its financial and sustainable contribution to the manufacturing sector. Jointly biotechnology and synthetic biology play a crucial role in generating cost-effective products with nature-friendly features by using bio-based production instead of fossil-based.[81] Synthetic biology can be used to engineer model microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli, by genome editing tools to enhance their ability to produce bio-based products, such as bioproduction of medicines and biofuels.[82] For instance, E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a consortium could be used as industrial microbes to produce precursors of the chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel by applying the metabolic engineering in a co-culture approach to exploit the benefits from the two microbes.[83]

Another example of synthetic biology applications in industrial biotechnology is the re-engineering of the metabolic pathways of E. coli by CRISPR and CRISPRi systems toward the production of a chemical known as 1,4-butanediol, which is used in fiber manufacturing. In order to produce 1,4-butanediol, the authors alter the metabolic regulation of the Escherichia coli by CRISPR to induce point mutation in the gltA gene, knockout of the sad gene, and knock-in six genes (cat1, sucD, 4hbd, cat2, bld, and bdh). Whereas CRISPRi system used to knockdown the three competing genes (gabD, ybgC, and tesB) that affect the biosynthesis pathway of 1,4-butanediol. Consequently, the yield of 1,4-butanediol significantly increased from 0.9 to 1.8 g/L.[84]

Environmental

Environmental biotechnology includes various disciplines that play an essential role in reducing environmental waste and providing environmentally safe processes, such as biofiltration and biodegradation.[85][86] The environment can be affected by biotechnologies, both positively and adversely. Vallero and others have argued that the difference between beneficial biotechnology (e.g., bioremediation is to clean up an oil spill or hazard chemical leak) versus the adverse effects stemming from biotechnological enterprises (e.g., flow of genetic material from transgenic organisms into wild strains) can be seen as applications and implications, respectively.[87] Cleaning up environmental wastes is an example of an application of environmental biotechnology; whereas loss of biodiversity or loss of containment of a harmful microbe are examples of environmental implications of biotechnology.

Regulation

The regulation of genetic engineering concerns approaches taken by governments to assess and manage the risks associated with the use of genetic engineering technology, and the development and release of genetically modified organisms (GMO), including genetically modified crops and genetically modified fish. There are differences in the regulation of GMOs between countries, with some of the most marked differences occurring between the US and Europe.[88] Regulation varies in a given country depending on the intended use of the products of the genetic engineering. For example, a crop not intended for food use is generally not reviewed by authorities responsible for food safety.[89] The European Union differentiates between approval for cultivation within the EU and approval for import and processing. While only a few GMOs have been approved for cultivation in the EU a number of GMOs have been approved for import and processing.[90] The cultivation of GMOs has triggered a debate about the coexistence of GM and non-GM crops. Depending on the coexistence regulations, incentives for the cultivation of GM crops differ.[91]

Learning

In 1988, after prompting from the United States Congress, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (National Institutes of Health) (NIGMS) instituted a funding mechanism for biotechnology training. Universities nationwide compete for these funds to establish Biotechnology Training Programs (BTPs). Each successful application is generally funded for five years then must be competitively renewed. Graduate students in turn compete for acceptance into a BTP; if accepted, then stipend, tuition and health insurance support are provided for two or three years during the course of their Ph.D. thesis work. Nineteen institutions offer NIGMS supported BTPs.[92] Biotechnology training is also offered at the undergraduate level and in community colleges.

References and notes

- ↑ "Biotechnology". IUPAC Goldbook. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.B00666. Retrieved February 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ↑ Biotechnology Archived November 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Portal.acs.org. Retrieved on March 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ What is biotechnology?. Europabio. Retrieved on March 20, 2013.

- ↑ Key Biotechnology Indicators (December 2011). oecd.org

- ↑ Biotechnology policies – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Oecd.org. Retrieved on March 20, 2013.

- ↑ "History, scope and development of biotechnology". iopscience.iop.org. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ↑ What Is Bioengineering? Archived January 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Bionewsonline.com. Retrieved on March 20, 2013.

- ↑ See Arnold JP (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology. Cleveland, Ohio: BeerBooks. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-9662084-1-2. OCLC 71834130..

- ↑ Cole-Turner R (2003). "Biotechnology". Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- 1 2 Thieman WJ, Palladino MA (2008). Introduction to Biotechnology. Pearson/Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-321-49145-9.

- ↑ Springham D, Springham G, Moses V, Cape RE (1999). Biotechnology: The Science and the Business. CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-90-5702-407-8.

- ↑ "Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980). No. 79-139." United States Supreme Court. June 16, 1980. Retrieved on May 4, 2007.

- ↑ "1960: Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Transistor Demonstrated". The Silicon Engine: A Timeline of Semiconductors in Computers. Computer History Museum. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ↑ Park, Jeho; Nguyen, Hoang Hiep; Woubit, Abdela; Kim, Moonil (2014). "Applications of Field-Effect Transistor (FET)–Type Biosensors". Applied Science and Convergence Technology. 23 (2): 61–71. doi:10.5757/ASCT.2014.23.2.61. ISSN 2288-6559. S2CID 55557610.

- ↑ Clark, Leland C.; Lyons, Champ (1962). "Electrode Systems for Continuous Monitoring in Cardiovascular Surgery". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 102 (1): 29–45. Bibcode:1962NYASA.102...29C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13623.x. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 14021529. S2CID 33342483.

- 1 2 3 Bergveld, Piet (October 1985). "The impact of MOSFET-based sensors" (PDF). Sensors and Actuators. 8 (2): 109–127. Bibcode:1985SeAc....8..109B. doi:10.1016/0250-6874(85)87009-8. ISSN 0250-6874.

- ↑ Chris Toumazou; Pantelis Georgiou (December 2011). "40 years of ISFET technology:From neuronal sensing to DNA sequencing". Electronics Letters. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ↑ Bergveld, P. (January 1970). "Development of an Ion-Sensitive Solid-State Device for Neurophysiological Measurements". IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. BME-17 (1): 70–71. doi:10.1109/TBME.1970.4502688. PMID 5441220.

- 1 2 3 Schöning, Michael J.; Poghossian, Arshak (September 10, 2002). "Recent advances in biologically sensitive field-effect transistors (BioFETs)" (PDF). Analyst. 127 (9): 1137–1151. Bibcode:2002Ana...127.1137S. doi:10.1039/B204444G. ISSN 1364-5528. PMID 12375833.

- ↑ VoIP Providers And Corn Farmers Can Expect To Have Bumper Years In 2008 And Beyond, According To The Latest Research Released By Business Information Analysts At IBISWorld. Los Angeles (March 19, 2008)

- ↑ "The Recession List - Top 10 Industries to Fly and Flop in 2008". Bio-Medicine.org. March 19, 2008. Archived from the original on June 2, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ↑ Gerstein, M. "Bioinformatics Introduction Archived 2007-06-16 at the Wayback Machine." Yale University. Retrieved on May 8, 2007.

- ↑ Siam, R. (2009). Biotechnology Research and Development in Academia: providing the foundation for Egypt's Biotechnology spectrum of colors. Sixteenth Annual American University in Cairo Research Conference, American University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt. BMC Proceedings, 31–35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Kafarski, P. (2012). Rainbow Code of Biotechnology Archived February 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. CHEMIK. Wroclaw University

- ↑ Biotech: true colours. (2009). TCE: The Chemical Engineer, (816), 26–31.

- ↑ Aldridge, S. (2009). The four colours of biotechnology: the biotechnology sector is occasionally described as a rainbow, with each sub sector having its own colour. But what do the different colours of biotechnology have to offer the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical Technology Europe, (1). 12.

- ↑ Frazzetto G (September 2003). "White biotechnology". EMBO Reports. 4 (9): 835–7. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.embor928. PMC 1326365. PMID 12949582.

- ↑ Frazzetto, G. (2003). White biotechnology. March 21, 2017, de EMBOpress Sitio

- ↑ Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology, Volume 135 2013, Yellow Biotechnology I

- ↑ Edgar, J.D. (2004). The Colours of Biotechnology: Science, Development and Humankind. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, (3), 01

- ↑ Ermak G. (2013) Modern Science & Future Medicine (second edition)

- ↑ Wang L (2010). "Pharmacogenomics: a systems approach". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1002/wsbm.42. PMC 3894835. PMID 20836007.

- ↑ Becquemont L (June 2009). "Pharmacogenomics of adverse drug reactions: practical applications and perspectives". Pharmacogenomics. 10 (6): 961–9. doi:10.2217/pgs.09.37. PMID 19530963.

- ↑ "Guidance for Industry Pharmacogenomic Data Submissions" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 2005. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ↑ Squassina A, Manchia M, Manolopoulos VG, Artac M, Lappa-Manakou C, Karkabouna S, Mitropoulos K, Del Zompo M, Patrinos GP (August 2010). "Realities and expectations of pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine: impact of translating genetic knowledge into clinical practice". Pharmacogenomics. 11 (8): 1149–67. doi:10.2217/pgs.10.97. PMID 20712531.

- ↑ Bains W (1987). Genetic Engineering For Almost Everybody: What Does It Do? What Will It Do?. Penguin. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-14-013501-5.

- 1 2 U.S. Department of State International Information Programs, "Frequently Asked Questions About Biotechnology", USIS Online; available from USinfo.state.gov Archived September 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 13, 2007. Cf. Feldbaum C (February 2002). "Biotechnology. Some history should be repeated". Science. 295 (5557): 975. doi:10.1126/science.1069614. PMID 11834802. S2CID 32595222.

- ↑ "What is genetic testing? – Genetics Home Reference". Ghr.nlm.nih.gov. May 30, 2011. Archived from the original on May 29, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Genetic Testing: MedlinePlus". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Definitions of Genetic Testing". Definitions of Genetic Testing (Jorge Sequeiros and Bárbara Guimarães). EuroGentest Network of Excellence Project. September 11, 2008. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- ↑ Genetically Altered Potato Ok'd For Crops Lawrence Journal-World – May 6, 1995

- ↑ National Academy of Sciences (2001). Transgenic Plants and World Agriculture. Washington: National Academy Press.

- ↑ Paarlburg R (January 2011). "Drought Tolerant GMO Maize in Africa, Anticipating Regulatory Hurdles" (PDF). International Life Sciences Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ↑ Carpenter J. & Gianessi L. (1999). Herbicide tolerant soybeans: Why growers are adopting Roundup Ready varieties Archived November 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. AgBioForum, 2(2), 65–72.

- ↑ Haroldsen VM, Paulino G, Chi-ham C, Bennett AB (2012). "Research and adoption of biotechnology strategies could improve California fruit and nut crops". California Agriculture. 66 (2): 62–69. doi:10.3733/ca.v066n02p62.

- ↑ About Golden Rice Archived November 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Irri.org. Retrieved on March 20, 2013.

- ↑ Gali Weinreb and Koby Yeshayahou for Globes May 2, 2012. FDA approves Protalix Gaucher treatment Archived May 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Carrington, Damien (January 19, 2012) GM microbe breakthrough paves way for large-scale seaweed farming for biofuels The Guardian. Retrieved March 12, 2012

- ↑ van Beilen JB, Poirier Y (May 2008). "Production of renewable polymers from crop plants". The Plant Journal. 54 (4): 684–701. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03431.x. PMID 18476872. S2CID 25954199.

- ↑ Strange, Amy (September 20, 2011) Scientists engineer plants to eat toxic pollution The Irish Times. Retrieved September 20, 2011

- ↑ Diaz E (editor). (2008). Microbial Biodegradation: Genomics and Molecular Biology (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-17-2.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - 1 2 3 James C (2011). "ISAAA Brief 43, Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2011". ISAAA Briefs. Ithaca, New York: International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ GM Science Review First Report Archived October 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Prepared by the UK GM Science Review panel (July 2003). Chairman Professor Sir David King, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK Government, P 9

- ↑ James C (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Consumer Q&A". Fda.gov. March 6, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ↑ "AquAdvantage Salmon". FDA. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ↑ Nicolia, Alessandro; Manzo, Alberto; Veronesi, Fabio; Rosellini, Daniele (2013). "An overview of the last 10 years of genetically engineered crop safety research" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 34 (1): 77–88. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.823595. PMID 24041244. S2CID 9836802.

We have reviewed the scientific literature on GE crop safety for the last 10 years that catches the scientific consensus matured since GE plants became widely cultivated worldwide, and we can conclude that the scientific research conducted so far has not detected any significant hazard directly connected with the use of GM crops.

The literature about Biodiversity and the GE food/feed consumption has sometimes resulted in animated debate regarding the suitability of the experimental designs, the choice of the statistical methods or the public accessibility of data. Such debate, even if positive and part of the natural process of review by the scientific community, has frequently been distorted by the media and often used politically and inappropriately in anti-GE crops campaigns. - ↑ "State of Food and Agriculture 2003–2004. Agricultural Biotechnology: Meeting the Needs of the Poor. Health and environmental impacts of transgenic crops". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

Currently available transgenic crops and foods derived from them have been judged safe to eat and the methods used to test their safety have been deemed appropriate. These conclusions represent the consensus of the scientific evidence surveyed by the ICSU (2003) and they are consistent with the views of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002). These foods have been assessed for increased risks to human health by several national regulatory authorities (inter alia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, the United Kingdom and the United States) using their national food safety procedures (ICSU). To date no verifiable untoward toxic or nutritionally deleterious effects resulting from the consumption of foods derived from genetically modified crops have been discovered anywhere in the world (GM Science Review Panel). Many millions of people have consumed foods derived from GM plants – mainly maize, soybean and oilseed rape – without any observed adverse effects (ICSU).

- ↑ Ronald, Pamela (May 1, 2011). "Plant Genetics, Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security". Genetics. 188 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128553. PMC 3120150. PMID 21546547.

There is broad scientific consensus that genetically engineered crops currently on the market are safe to eat. After 14 years of cultivation and a cumulative total of 2 billion acres planted, no adverse health or environmental effects have resulted from commercialization of genetically engineered crops (Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Committee on Environmental Impacts Associated with Commercialization of Transgenic Plants, National Research Council and Division on Earth and Life Studies 2002). Both the U.S. National Research Council and the Joint Research Centre (the European Union's scientific and technical research laboratory and an integral part of the European Commission) have concluded that there is a comprehensive body of knowledge that adequately addresses the food safety issue of genetically engineered crops (Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health and National Research Council 2004; European Commission Joint Research Centre 2008). These and other recent reports conclude that the processes of genetic engineering and conventional breeding are no different in terms of unintended consequences to human health and the environment (European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation 2010).

- ↑

But see also:

Domingo, José L.; Bordonaba, Jordi Giné (2011). "A literature review on the safety assessment of genetically modified plants" (PDF). Environment International. 37 (4): 734–742. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2011.01.003. PMID 21296423.

In spite of this, the number of studies specifically focused on safety assessment of GM plants is still limited. However, it is important to remark that for the first time, a certain equilibrium in the number of research groups suggesting, on the basis of their studies, that a number of varieties of GM products (mainly maize and soybeans) are as safe and nutritious as the respective conventional non-GM plant, and those raising still serious concerns, was observed. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that most of the studies demonstrating that GM foods are as nutritional and safe as those obtained by conventional breeding, have been performed by biotechnology companies or associates, which are also responsible of commercializing these GM plants. Anyhow, this represents a notable advance in comparison with the lack of studies published in recent years in scientific journals by those companies.

Krimsky, Sheldon (2015). "An Illusory Consensus behind GMO Health Assessment". Science, Technology, & Human Values. 40 (6): 883–914. doi:10.1177/0162243915598381. S2CID 40855100.

I began this article with the testimonials from respected scientists that there is literally no scientific controversy over the health effects of GMOs. My investigation into the scientific literature tells another story.

And contrast:

Panchin, Alexander Y.; Tuzhikov, Alexander I. (January 14, 2016). "Published GMO studies find no evidence of harm when corrected for multiple comparisons". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 37 (2): 213–217. doi:10.3109/07388551.2015.1130684. ISSN 0738-8551. PMID 26767435. S2CID 11786594.

Here, we show that a number of articles some of which have strongly and negatively influenced the public opinion on GM crops and even provoked political actions, such as GMO embargo, share common flaws in the statistical evaluation of the data. Having accounted for these flaws, we conclude that the data presented in these articles does not provide any substantial evidence of GMO harm.

The presented articles suggesting possible harm of GMOs received high public attention. However, despite their claims, they actually weaken the evidence for the harm and lack of substantial equivalency of studied GMOs. We emphasize that with over 1783 published articles on GMOs over the last 10 years it is expected that some of them should have reported undesired differences between GMOs and conventional crops even if no such differences exist in reality.and

Yang, Y.T.; Chen, B. (2016). "Governing GMOs in the USA: science, law and public health". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 96 (4): 1851–1855. doi:10.1002/jsfa.7523. PMID 26536836.It is therefore not surprising that efforts to require labeling and to ban GMOs have been a growing political issue in the USA (citing Domingo and Bordonaba, 2011). Overall, a broad scientific consensus holds that currently marketed GM food poses no greater risk than conventional food... Major national and international science and medical associations have stated that no adverse human health effects related to GMO food have been reported or substantiated in peer-reviewed literature to date.

Despite various concerns, today, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the World Health Organization, and many independent international science organizations agree that GMOs are just as safe as other foods. Compared with conventional breeding techniques, genetic engineering is far more precise and, in most cases, less likely to create an unexpected outcome. - ↑ "Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors On Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods" (PDF). American Association for the Advancement of Science. October 20, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

The EU, for example, has invested more than €300 million in research on the biosafety of GMOs. Its recent report states: "The main conclusion to be drawn from the efforts of more than 130 research projects, covering a period of more than 25 years of research and involving more than 500 independent research groups, is that biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than e.g. conventional plant breeding technologies." The World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the British Royal Society, and every other respected organization that has examined the evidence has come to the same conclusion: consuming foods containing ingredients derived from GM crops is no riskier than consuming the same foods containing ingredients from crop plants modified by conventional plant improvement techniques.

Pinholster, Ginger (October 25, 2012). "AAAS Board of Directors: Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could "Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers"" (PDF). American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved August 30, 2019. - ↑ European Commission. Directorate-General for Research (2010). A decade of EU-funded GMO research (2001–2010) (PDF). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Biotechnologies, Agriculture, Food. European Commission, European Union. doi:10.2777/97784. ISBN 978-92-79-16344-9. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ "AMA Report on Genetically Modified Crops and Foods (online summary)". American Medical Association. January 2001. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

A report issued by the scientific council of the American Medical Association (AMA) says that no long-term health effects have been detected from the use of transgenic crops and genetically modified foods, and that these foods are substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts. (from online summary prepared by ISAAA)" "Crops and foods produced using recombinant DNA techniques have been available for fewer than 10 years and no long-term effects have been detected to date. These foods are substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts.

(from original report by AMA: ){{cite web}}: External link in|quote=Bioengineered foods have been consumed for close to 20 years, and during that time, no overt consequences on human health have been reported and/or substantiated in the peer-reviewed literature.

- ↑ "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms: United States. Public and Scholarly Opinion". Library of Congress. June 30, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

Several scientific organizations in the US have issued studies or statements regarding the safety of GMOs indicating that there is no evidence that GMOs present unique safety risks compared to conventionally bred products. These include the National Research Council, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Medical Association. Groups in the US opposed to GMOs include some environmental organizations, organic farming organizations, and consumer organizations. A substantial number of legal academics have criticized the US's approach to regulating GMOs.

- ↑ National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering; Division on Earth Life Studies; Board on Agriculture Natural Resources; Committee on Genetically Engineered Crops: Past Experience Future Prospects (2016). Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (US). p. 149. doi:10.17226/23395. ISBN 978-0-309-43738-7. PMID 28230933. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

Overall finding on purported adverse effects on human health of foods derived from GE crops: On the basis of detailed examination of comparisons of currently commercialized GE with non-GE foods in compositional analysis, acute and chronic animal toxicity tests, long-term data on health of livestock fed GE foods, and human epidemiological data, the committee found no differences that implicate a higher risk to human health from GE foods than from their non-GE counterparts.

- ↑ "Frequently asked questions on genetically modified foods". World Health Organization. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

Different GM organisms include different genes inserted in different ways. This means that individual GM foods and their safety should be assessed on a case-by-case basis and that it is not possible to make general statements on the safety of all GM foods.

GM foods currently available on the international market have passed safety assessments and are not likely to present risks for human health. In addition, no effects on human health have been shown as a result of the consumption of such foods by the general population in the countries where they have been approved. Continuous application of safety assessments based on the Codex Alimentarius principles and, where appropriate, adequate post market monitoring, should form the basis for ensuring the safety of GM foods. - ↑ Haslberger, Alexander G. (2003). "Codex guidelines for GM foods include the analysis of unintended effects". Nature Biotechnology. 21 (7): 739–741. doi:10.1038/nbt0703-739. PMID 12833088. S2CID 2533628.

These principles dictate a case-by-case premarket assessment that includes an evaluation of both direct and unintended effects.

- ↑ Some medical organizations, including the British Medical Association, advocate further caution based upon the precautionary principle:

"Genetically modified foods and health: a second interim statement" (PDF). British Medical Association. March 2004. Retrieved August 30, 2019.In our view, the potential for GM foods to cause harmful health effects is very small and many of the concerns expressed apply with equal vigour to conventionally derived foods. However, safety concerns cannot, as yet, be dismissed completely on the basis of information currently available.

When seeking to optimise the balance between benefits and risks, it is prudent to err on the side of caution and, above all, learn from accumulating knowledge and experience. Any new technology such as genetic modification must be examined for possible benefits and risks to human health and the environment. As with all novel foods, safety assessments in relation to GM foods must be made on a case-by-case basis.

Members of the GM jury project were briefed on various aspects of genetic modification by a diverse group of acknowledged experts in the relevant subjects. The GM jury reached the conclusion that the sale of GM foods currently available should be halted and the moratorium on commercial growth of GM crops should be continued. These conclusions were based on the precautionary principle and lack of evidence of any benefit. The Jury expressed concern over the impact of GM crops on farming, the environment, food safety and other potential health effects.

The Royal Society review (2002) concluded that the risks to human health associated with the use of specific viral DNA sequences in GM plants are negligible, and while calling for caution in the introduction of potential allergens into food crops, stressed the absence of evidence that commercially available GM foods cause clinical allergic manifestations. The BMA shares the view that there is no robust evidence to prove that GM foods are unsafe but we endorse the call for further research and surveillance to provide convincing evidence of safety and benefit. - ↑ Funk, Cary; Rainie, Lee (January 29, 2015). "Public and Scientists' Views on Science and Society". Pew Research Center. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

The largest differences between the public and the AAAS scientists are found in beliefs about the safety of eating genetically modified (GM) foods. Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) scientists say it is generally safe to eat GM foods compared with 37% of the general public, a difference of 51 percentage points.

- ↑ Marris, Claire (2001). "Public views on GMOs: deconstructing the myths". EMBO Reports. 2 (7): 545–548. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve142. PMC 1083956. PMID 11463731.

- ↑ Final Report of the PABE research project (December 2001). "Public Perceptions of Agricultural Biotechnologies in Europe". Commission of European Communities. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Scott, Sydney E.; Inbar, Yoel; Rozin, Paul (2016). "Evidence for Absolute Moral Opposition to Genetically Modified Food in the United States" (PDF). Perspectives on Psychological Science. 11 (3): 315–324. doi:10.1177/1745691615621275. PMID 27217243. S2CID 261060.

- ↑ "Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms". Library of Congress. June 9, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Bashshur, Ramona (February 2013). "FDA and Regulation of GMOs". American Bar Association. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Sifferlin, Alexandra (October 3, 2015). "Over Half of E.U. Countries Are Opting Out of GMOs". Time. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Lynch, Diahanna; Vogel, David (April 5, 2001). "The Regulation of GMOs in Europe and the United States: A Case-Study of Contemporary European Regulatory Politics". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ↑ Pollack A (April 13, 2010). "Study Says Overuse Threatens Gains From Modified Crops". The New York Times.

- ↑ Industrial Biotechnology and Biomass Utilisation Archived April 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Industrial biotechnology, A powerful, innovative technology to mitigate climate change". Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ↑ Clarke, Lionel; Kitney, Richard (February 28, 2020). "Developing synthetic biology for industrial biotechnology applications". Biochemical Society Transactions. 48 (1): 113–122. doi:10.1042/BST20190349. ISSN 0300-5127. PMC 7054743. PMID 32077472.

- ↑ McCarty, Nicholas S.; Ledesma-Amaro, Rodrigo (February 2019). "Synthetic Biology Tools to Engineer Microbial Communities for Biotechnology". Trends in Biotechnology. 37 (2): 181–197. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.11.002. ISSN 0167-7799. PMC 6340809. PMID 30497870.

- ↑ Zhou, Kang; Qiao, Kangjian; Edgar, Steven; Stephanopoulos, Gregory (April 2015). "Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products". Nature Biotechnology. 33 (4): 377–383. doi:10.1038/nbt.3095. ISSN 1087-0156. PMC 4867547. PMID 25558867.

- ↑ Wu, Meng-Ying; Sung, Li-Yu; Li, Hung; Huang, Chun-Hung; Hu, Yu-Chen (December 15, 2017). "Combining CRISPR and CRISPRi Systems for Metabolic Engineering of E. coli and 1,4-BDO Biosynthesis". ACS Synthetic Biology. 6 (12): 2350–2361. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00251. ISSN 2161-5063. PMID 28854333.

- ↑ Pakshirajan, Kannan; Rene, Eldon R.; Ramesh, Aiyagari (2014). "Biotechnology in environmental monitoring and pollution abatement". BioMed Research International. 2014: 235472. doi:10.1155/2014/235472. ISSN 2314-6141. PMC 4017724. PMID 24864232.

- ↑ Danso, Dominik; Chow, Jennifer; Streit, Wolfgang R. (October 1, 2019). "Plastics: Environmental and Biotechnological Perspectives on Microbial Degradation". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 85 (19). doi:10.1128/AEM.01095-19. ISSN 1098-5336. PMC 6752018. PMID 31324632.

- ↑ Daniel A. Vallero, Environmental Biotechnology: A Biosystems Approach, Academic Press, Amsterdam, NV; ISBN 978-0-12-375089-1; 2010.

- ↑ Gaskell G, Bauer MW, Durant J, Allum NC (July 1999). "Worlds apart? The reception of genetically modified foods in Europe and the U.S". Science. 285 (5426): 384–7. doi:10.1126/science.285.5426.384. PMID 10411496. S2CID 5131870.

- ↑ "The History and Future of GM Potatoes". Potato Pro. March 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ↑ Wesseler J, Kalaitzandonakes N (2011). "Present and Future EU GMO policy". In Oskam A, Meesters G, Silvis H (eds.). EU Policy for Agriculture, Food and Rural Areas (2nd ed.). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. pp. 23–332.

- ↑ Beckmann VC, Soregaroli J, Wesseler J (2011). "Coexistence of genetically modified (GM) and non-modified (non GM) crops: Are the two main property rights regimes equivalent with respect to the coexistence value?". In Carter C, Moschini G, Sheldon I (eds.). Genetically modified food and global welfare. Frontiers of Economics and Globalization Series. Vol. 10. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 201–224.

- ↑ "Biotechnology Predoctoral Training Program". National Institute of General Medical Sciences. December 18, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Biotechnology. |

| At Wikiversity, you can learn more and teach others about Biotechnology at the Department of Biotechnology |

- Foundation for Biotechnology Awareness and Education,

- A report on Agricultural Biotechnology focusing on the impacts of "Green" Biotechnology with a special emphasis on economic aspects. fao.org.

- US Economic Benefits of Biotechnology to Business and Society NOAA Economics, economics.noaa.gov

- Database of the Safety and Benefits of Biotechnology – a database of peer-reviewed scientific papers and the safety and benefits of biotechnology.

- What is Biotechnology? – A curated collection of resources about the people, places and technologies that have enabled biotechnology to transform the world we live in today

- Applied Food Biotechnology focusing on disseminate knowledge in all the related areas of biomass, metabolites, biological waste treatment, biotransformation, and bioresource systems analysis, and technologies associated with conversion or production in the field of Food.