Autotransfusion

| Autotransfusion | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, surgery, hematology |

Autotransfusion is a process wherein a person receives their own blood for a transfusion, instead of banked allogenic (separate-donor) blood. There are two main kinds of autotransfusion: Blood can be autologously "pre-donated" (termed so despite "donation" not typically referring to giving to one's self) before a surgery, or alternatively, it can be collected during and after the surgery using an intraoperative blood salvage device (such as a Cell Saver, HemoClear or CATS). The latter form of autotransfusion is utilized in surgeries where there is expected a large volume blood loss – e.g. aneurysm, total joint replacement, and spinal surgeries. The effectiveness, safety, and cost-savings of intraoperative cell salvage in people who are undergoing thoracic or abdominal surgery following trauma is not known.[1]

The first documented use of "self-donated" blood was in 1818, and interest in the practice continued until the Second World War, at which point blood supply became less of an issue due to the increased number of blood donors. Later, interest in the procedure returned with concerns about allogenic (separate-donor) transfusions. Autotransfusion is used in a number of orthopedic, trauma, and cardiac cases, amongst others. Where appropriate, it carries certain advantages –including the reduction of infection risk, and the provision of more functional cells not subjected to the significant storage durations common among banked allogenic (separate-donor) blood products.

Autotransfusion also refers to the natural process, where (during fetal delivery) the uterus naturally contracts, shunting blood back into the maternal circulation.[2] This is important in pregnancy, because the uterus (at the later stages of fetal development) can hold as much as 16% of the mother's blood supply [2]

Medical uses

Autotransfusion is intended for use in situations characterized by the loss of one or more units of blood and may be particularly advantageous for use in cases involving rare blood groups, risk of infectious disease transmission, restricted homologous blood supply or other medical situations for which the use of homologous blood is contraindicated. Autotransfusion is commonly used intraoperatively and postoperatively. Intraoperative autotransfusion refers to recovery of blood lost during surgery or the concentration of fluid in an extracorporeal circuit. Postoperative autotransfusion refers to the recovery of blood in the extracorporeal circuit at the end of surgery or from aspirated drainage.[3] Further clinical research in the form of randomized controlled trials is required to determine the effectiveness and safety of this procedure due abdominal or thoracic trauma surgery.[1]

Advantages

- High levels of 2,3-DPG

- Normothermic

- pH relatively normal

- Lower risk of infectious diseases

- Functionally superior cells

- Lower potassium (compared to stored blood)

- Quickly available

- May reduce the need for allogeneic red cell transfusion during certain surgeries, such as, adult elective cardiac and orthopaedic surgery.[4]

Substances washed out

- Plasma

- Platelets

- White cells

- Anticoagulant solution

- Plasma free hemoglobin

- Cellular stroma

- Activated clotting factors

- Intracellular enzymes

- Potassium

- Plasma bound antibiotics

Side effects

The disadvantage of autotransfusion is the depletion of plasma and platelets. The washed autotransfusion system removes the plasma and platelets to eliminate activated clotting factors and activated platelets which would cause coagulopathy if they were reinfused to the patient, generating a packed red blood cell (PRBC) product. This disadvantage is only evident when very large blood losses occur. The autotransfusionist monitors blood loss and will recommend the transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelets when the blood loss and return of autotransfusion blood increase. Typically the patient will require FFP and platelets as the estimated blood loss exceeds half of the patient's blood volume. When possible diagnostic tests should be performed to determine the need for any blood products (i.e. PRBC, FFP and platelets).

Contraindications

The use of blood recovered from the operative field is contraindicated in the presence of bacterial contamination or malignancy. The use of autotransfusion in the presence of such contamination may result in the dissemination of pathologic microorganisms or malignant cells. The following statements reflect current clinical concerns involving autotransfusion contraindications.[3]

Contamination of the surgical site

Any abdominal procedure poses the risk of enteric contamination of shed blood. The surgical team must be diligent in observing for signs of bowel contamination of the blood. If there is a question of possible contamination the blood may be held until the surgeon determines whether or not bowel contents are in the surgical field. If the blood is contaminated the entire contents should be discarded. If the patient's life depends upon this blood supply it may be reinfused with the surgeon's consent. While washing with large amounts of a sodium chloride solution will reduce the bacterial contamination of the blood, it will not be totally eliminated.

Malignancy

There is a possibility of the reinfusion of cancer cells from the surgical site.[5] There are possible exceptions to this contraindication:

- The surgeon feels complete removal of an encapsulated tumor is possible. Blood may be aspirated from the surgical site, processed and reinfused with the surgeon's consent.

- If an inadequate supply of blood exists, the washed red cells may be used to support the patient's vital signs with the surgeon's consent.

The use of leukocyte reduction filters is recommended.

Obstetrics

Autotransfusion is not normally used in Caesarean sections, because the possibility of an amniotic fluid embolism exists. Emerging literature suggests that amniotic fluid is being cleared during the wash cycle. It is possible that the utilization of autotransfusion in obstetrics may increase as more research is completed. However, if a patient is at risk for blood loss and is a Jehovah's witness, for example, the cell saver can be used with strict guidelines of irrigating profusely to remove amniotic fluid and then suctioning the blood that is being lost.

Emergency

In life saving situations with the consent of the surgeon, autotransfusion can be utilized in the presence of the previous stated contraindications i.e. sepsis, bowel contamination and malignancy.

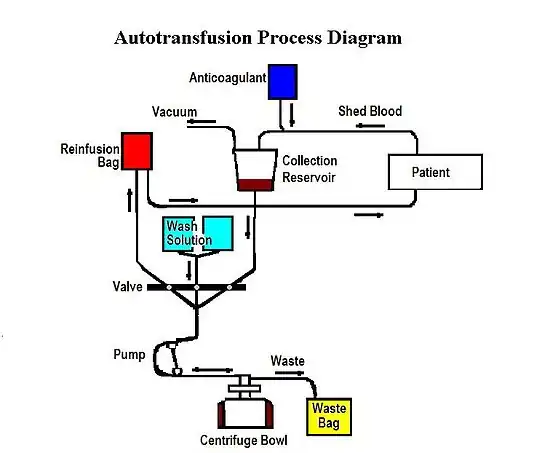

Collection and processing of blood

Utilizing a special double lumen suction tubing, fluid is aspirated from the operative field and is mixed with an anticoagulant solution. Collected fluid is filtered in a sterile cardiotomy reservoir. The reservoir contains filter and has a capacity of between two and three liters of fluid. When a volume adequate to fill the wash bowl has been collected, processing may begin. The volume required to fill the bowl is dependent on the hematocrit (HCT) and size of the centrifuge wash bowl. If the patients HCT is normal, the amount needed to process a unit is roughly two times the bowl volume.[6]

When aspirating the blood it is important to utilize the following technique whenever possible:

- Suction blood from pools rather than skimming.

- Keep the suction tip below the level of the air-blood interface.

- Avoid occluding the suction tip (i.e. using suction as a retractor).

Following these techniques will help reduce hemolysis of the red cells and will help increase the amount of red cells that will be salvaged.

Special considerations

Antibiotic irrigation

Antibiotics that are plasma bound can be removed during the autotransfusion wash cycle, however, topical antibiotics which are typically not plasma bound may not be washed out during autotransfusion, and may actually become concentrated to the point of being nephrotoxic.

Topical coagulant products

When Avitene, Hemopad, Instat, or collagen type products are used, autotransfusion should be interrupted and a waste or wall suction source must be used. Autotransfusion can be resumed once these products are flushed from the surgical site. If Gelfoam, Surgicel, Thrombogen or Thrombostat are used, autotransfusion can continue, however, direct suctioning of these products should be avoided.

Orthopedic bone cement

Cement is often used or encountered during primary or revision total joint replacement surgery. Cement in the liquid or soft state should not be introduced into the autotransfusion system. When cement is being applied a waste or wall suction source must be used, however when the cement hardens autotransfusion may be resumed. The use of ultrasonic equipment during revision of total joints changes the cement to a liquid or soft state, which precludes the use of autotransfusion during the use of such equipment. Autotransfusion can only continue when the cement has hardened.

Processing

Prime phase

In the prime phase, the centrifuge begins rotation and accelerates to the speed selected on the centrifuge speed control, typically 5,600 rpm. Simultaneously, the pump begins counterclockwise rotation, enabling the transfer of the reservoir contents to the wash bowl. The application of centrifugal force separates the components of the fluid according to their weight. The wash bowl filling continues until the buffy coat reaches the shoulder of the wash bowl. Some autotransfusion devices have automatic features including a buffy coat sensor, which is calibrated to detect a full bowl and advance the process to the wash phase automatically.

Wash phase

The wash phase begins when the wash bowl is appropriately filled with red cells. The pump continues a counterclockwise rotation and clamps adjust, enabling the transfer of wash solution to the wash bowl. The washing phase removes cellular stromata, plasma free hemoglobin, anticoagulant solution, activated clotting factors, any plasma bound antibiotics, intracellular enzymes, plasma, platelets, and white cells. The unwanted fluid passes out of the wash bowl and into a waste reservoir bag. Washing continues until the reinfuse button is depressed (or the program ends, in the case of an automatic device) and the appropriate amount of wash solution has been delivered to the wash bowl. The wash phase is terminated when one to two liters of wash solution has been transferred, or the fluid transferred to the waste bag appears transparent (or both).

Empty phase

When the empty phase is initiated, the centrifuge begins braking. The clamps change positions, enabling the transfer of the wash bowl contents to the reinfusion bag. The centrifuge bowl must come to a complete stop before the pump begins a clockwise rotation to empty the bowl. Once the bowl is emptied, the cycle is ended and a new cycle can be begun. The reinfusion bag attached to the autotransfusion wash set should not be used for high pressure infusion back to the patient. The reinfusion bag contains a significant amount of air, careful monitoring should take place during reinfusion to avoid the potential of air embolism. Therefore, it is recommended to use a separate blood bag attached to the reinfusion bag. This second bag can then be disconnected, air purged from it, and then tied off before giving to anesthesia for reinfusion. Thus reducing the chances of an air embolism. In accordance with Guidelines set by the American Association of Blood Banks the blood should be reinfused within 4 hours from washing.

Postoperative autotransfusion

Postoperative autotransfusion is performed by connecting the double lumen autotransfusion suction line directly to the drain line placed at the conclusion of surgery. Postoperative autotransfusion begins in the operating room when the drain line is placed and the surgical site is closed. Typical postoperative cases are total knee and hip replacements. Autotransfusion is continued and is effective while the patient actively bleeds during the immediate postoperative phase of recovery. Autotransfusion is ended when bleeding is stopped or is significantly slow, and is discontinued by connecting an ordinary self draining device to the drain lines. Available for postoperative autotransfusion are universal bifurcated connectors which can accommodate two drain lines of any size, these connectors can be attached to the standard ten foot double lumen suction line for postoperative use.

Soaking sponges

In some institutions to maximize the effectiveness of autotransfusion and provide the best conservation and return of red cells the soaking of sponges is employed. During the surgical procedure the blood soaked sponges are collected and placed in a sterile basin by the surgical team, sterile heparinized saline is added to the basin to prevent clotting and facilitate the release of red cells. The sponges are periodically wrung out and removed from the basin, the remaining solution can be suctioned into the autotransfusion reservoir so that the red cells can be recovered. The usual ratio of heparinized saline is 5,000 units of heparin per 1,000 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride. The heparin is removed during the autotransfusion process.[7][8]

History

There is some evidence that in 1785 Philip Physic of Philadelphia transfused a post-partum patient.[9] However the first documented use of autologous blood transfusion was in 1818 when an Englishman, Rey Paul Blundell, salvaged vaginal blood from patients with postpartum hemorrhage. By swabbing the blood from the bleeding site and rinsing the swabs with saline, he found that he could re-infuse the result of the washings. This unsophisticated method resulted in a 75% mortality rate, but it marked the start of autologous blood transfusion.[10]

During the American Civil War Union Army physicians are said to have administered four transfusions. In 1886, J. Duncan used autotransfusion during the amputation of limbs by removing blood from the amputated limb and returning it to the patient by femoral injection. This method was apparently fairly successful.[11] A German, M. J. Theis, reported the first successful use of intraoperative autotransfusion in 1914, with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy.[12] The earliest report in the American literature on the use of autotransfusion was by Lockwood in 1917 who used the technique during a splenectomy for Banti syndrome.[13] Interest in the unrefined technique of autotransfusion continued through to the early 1940s, and was applied to various procedures including treatment of ectopic pregnancy,[14][15] hemothorax,[16] ruptured spleen,[17][18] perforating abdominal injuries,[19] and neurosurgical procedures.[20]

The interest in autotransfusion dwindled during World War II, when there was a large pool of donors. After the war, blood testing, typing, and crossmatching techniques were improved making blood banks the answer to the increased demand for blood. In the 1960s, interest in autotransfusion revived. With the advances in all fields of surgery, new companies developed autotransfusion devices. Problems still arose, however, with air embolism, coagulopathy, and hemolysis.[21] The devices used during the Korean and Vietnam War collected and provided gross filtration of blood before it was reinfused.[22] With the introduction of cardiopulmonary bypass in 1952, autotransfusion became an area of study. Klebanoff began a new era of autotransfusion by developing the first commercially available autotransfusion unit in 1968.[23] His system, the Bentley Autotransfusion System aspirated, collected, filtered and reinfused autologous whole blood shed from the operative field. The problems with the Bentley system included the requirement of systemic anticoagulation of the patient, introduction of air embolism, and renal failure resulting from unfiltered particulate in the reinfused blood.

As the Bentley system lost favor Wilson and associates proposed the use of a discontinuous flow centrifuge process for autotransfusion which would wash the red cells with normal saline solution.[24] In 1976, this system was introduced by Haemonetics Corp. and is known commonly as "Cell Saver".[25] More recently in 1995 Fresenius introduced a continuous autotransfusion system.[26]

There are three types of systems: un-washed filtered blood; discontinuous flow centrifugal; and continuous flow centrifugal. The unwashed systems are popular because of their perceived inexpense and simplicity. However unwashed systems can cause increase potential for clinical complications. The washed system requires a properly trained and clinically skilled operator. It returns only red blood cells suspended in saline and is rarely associated with any clinical complications. Discontinuous autotransfusion can practically eliminate the need for exposure to homologous blood in elective surgical patients and can greatly reduce the risk of exposure to emergency surgical patients.

Society and culture

Individuals of the Jehovah's Witness religion in particular refuse to accept homologous and autologous pre-donated blood. However some individual members may accept the use of autotransfusion by means of the Cell Saver. The process of autotransfusion using the Cell Saver is modified to maintain a continuous circuit of blood that maintains continuous contact with the body. This process when carefully explained to the patient may be acceptable when a patient otherwise refuses based on religious beliefs.

Platelet sequestration and autologous platelet gel

Many of the newest autotransfusion machines are programmable to provide separation of blood into three groups; red cells, platelet poor plasma, and platelet rich plasma. Blood can be drawn from the patient just prior to surgery and then separated. The separated blood components which have been sequestered can be stored during the surgical procedure. The red cells and platelet poor plasma can be given back to the patient through intravenous transfusion during or after surgery. The platelet rich plasma can be mixed with calcium and thrombin to create a product known as autologous platelet gel. This is an autologous product that can be used for a variety of techniques including use as a hemostatic aid, a dural sealant, and an aid to fusion of bone.

See also

References

- 1 2 Li, Jiang; Sun, Shao Liang; Tian, Jin Hui; Yang, KeHu; Liu, Ruifeng; Li, Jun (2015-01-23). "Cell salvage in emergency trauma surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD007379. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007379.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8406788. PMID 25613473.

- 1 2 Caroline, Nancy L. (2018). Nancy Caroline's Emergency Care in the Streets 8th Edition. y American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). p. 2030. ISBN 9781284104882.

- 1 2 Dideco Shiley BT795/AA Machine Operation Manual, Shiley Incorporated, Irvine CA, 1988, page 3

- ↑ Carless, Paul A.; Henry, David A.; Moxey, Annette J.; O'Connell, Dianne; Brown, Tamara; Fergusson, Dean A. (2010-04-14). Carless, Paul A. (ed.). "Cell salvage for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001888. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001888.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4163967. PMID 20393932.

- ↑ Harlaar, JJ; Gosselink, MP; Hop, WC; Lange, JF; Busch, OR; Jeekel, H (Nov 2012). "Blood transfusions and prognosis in colorectal cancer: long-term results of a randomized controlled trial". Annals of Surgery. 256 (5): 681–7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318271cedf. PMID 23095610. S2CID 35798344.

- ↑ Dideco Shiley BT795/AA Machine Operation Manual, Shiley Incorporated, Irvine CA, 1988, page 19

- ↑ Drago, S. S. (1992), "Banking on your own blood", Am J Nurs, 92 (3): 61–4, doi:10.2307/3426653, JSTOR 3426653, PMID 1536207

- ↑ Langone J, 1988, New methods for saving blood. Researchers are trying to reclaim, recycle and replenish it., Time, 5; 132(23):57, Dec 5, 1988.

- ↑ Schmidt, P. J. (1968), "Transfusion in America in the eighteenth and nineteenth century", N Engl J Med, 279 (24): 1319–20, doi:10.1056/NEJM196812122792406, PMID 4880439

- ↑ Blundell, J. (1918), "Experiments on the transfusion of blood by syringe", Medico-Chirurical Journal, 9 (Pt 1): 59, doi:10.1177/09595287180090p107, PMC 2128869, PMID 20895353

- ↑ Duncan, J. (1886), "On Re-Infusion of Blood in Primary and Other Amputations", Br Med J, 1 (1309): 192–3, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1309.192, PMC 2256603, PMID 20751443

- ↑ Thies, H. J. (1914), "Zur Behandlung der Extrauteringraviditar", ZBL Gynaek, 38: 1190

- ↑ Lockwood, C. D. (1917), "Surgical treatment of bantis disease", Surg Gynec Obstet, 25: 188

- ↑ Maynard, R. L. (1929), "Case of ruptured extra-uterine pregnancy treated by autotransfusion", JAMA, 92 (21): 1758, doi:10.1001/jama.1929.92700470001012

- ↑ Rumbaugh, M. C. (1931), "Ruptured tubal pregnancy: report of a case in which life was saved by autotransfusion of blood", Penn Med, 34: 710

- ↑ Brown, A. L. (1931), "Autotransfusion: use of blood from hemothorax", JAMA, 96: 1223, doi:10.1001/jama.1931.02720410033012

- ↑ Coley, B. L. (1928), "Traumatic rupture of spleen, splenectomy, autotransfusion", Am J Surg, 4 (3): 34, doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(28)90352-9

- ↑ Downing, W. (1934), "Autotransfusion following rupture of the spleen: case report", J Iowa Med Soc, 24: 246

- ↑ Griswald, R. A. (1943), "The use of autotransfusion in surgery of the serous cavities", Surg Gynec & Obstet, 77: 167

- ↑ Davis, L. E. (1925), "Experiences with blood replacement during or after major intra-cranial operations", Surg Gynec Obstet, 40: 310

- ↑ Nicholson E, 1988, Autolgous blood transfusion, Nurs Times, 13-19; 84(2):33-5 Jan 1988

- ↑ Autologous Blood Transfusion Education Program, Training Manual, Shiley Incorporated, Irvine CA, 1992

- ↑ Klebanoff, G. (1970), "Early Clinical experience with a disposable unit for intraoperative salvage and reinfusion of blood loss (intraoperative autotransfusion)", Am J Surg, 120 (6): 718–722, doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(70)90066-8, PMID 5488321

- ↑ Wilson, J. D.; Utz, DC; Taswell, HF (1969), "Autotransfusion during transurethral resection of the prostate: Technique and preliminary clinical evaluation", Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 44 (6): 374–86, PMID 4183315

- ↑ Healey, T. G. (1989), "AANA Journal course: New technologies in anesthesia: Update for nurse anesthetists- Intraoperative blood salvage", AANA Journal, 57 (5): 429–34, PMID 2603623

- ↑ Fresenius