Denitrification

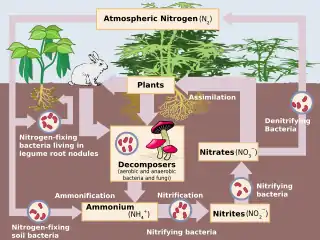

Denitrification is a microbially facilitated process where nitrate (NO3−) is reduced and ultimately produces molecular nitrogen (N2) through a series of intermediate gaseous nitrogen oxide products. Facultative anaerobic bacteria perform denitrification as a type of respiration that reduces oxidized forms of nitrogen in response to the oxidation of an electron donor such as organic matter. The preferred nitrogen electron acceptors in order of most to least thermodynamically favorable include nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), nitric oxide (NO), nitrous oxide (N2O) finally resulting in the production of dinitrogen (N2) completing the nitrogen cycle. Denitrifying microbes require a very low oxygen concentration of less than 10%, as well as organic C for energy. Since denitrification can remove NO3−, reducing its leaching to groundwater, it can be strategically used to treat sewage or animal residues of high nitrogen content. Denitrification can leak N2O, which is an ozone-depleting substance and a greenhouse gas that can have a considerable influence on global warming.

The process is performed primarily by heterotrophic bacteria (such as Paracoccus denitrificans and various pseudomonads),[1] although autotrophic denitrifiers have also been identified (e.g., Thiobacillus denitrificans).[2] Denitrifiers are represented in all main phylogenetic groups.[3] Generally several species of bacteria are involved in the complete reduction of nitrate to N2, and more than one enzymatic pathway has been identified in the reduction process.[4] The denitrification process does not only provide energy to the organism performing nitrate reduction to dinitrogen gas, but also some anaerobic ciliates can use denitrifying endosymbionts to gain energy similar to the use of mitochondria in oxygen respiring organisms.[5]

Direct reduction from nitrate to ammonium, a process known as dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium or DNRA,[6] is also possible for organisms that have the nrf-gene.[7][8] This is less common than denitrification in most ecosystems as a means of nitrate reduction. Other genes known in microorganisms which denitrify include nir (nitrite reductase) and nos (nitrous oxide reductase) among others;[3] organisms identified as having these genes include Alcaligenes faecalis, Alcaligenes xylosoxidans, many in the genus Pseudomonas, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and Blastobacter denitrificans.[9]

Overview

Half reactions

Denitrification generally proceeds through some combination of the following half reactions, with the enzyme catalyzing the reaction in parentheses:

- NO3− + 2 H+ + 2 e−→ NO

2− + H2O (Nitrate reductase) - NO

2− + 2 H+ + e− → NO + H2O (Nitrite reductase) - 2 NO + 2 H+ + 2 e− → N

2O + H2O (Nitric oxide reductase) - N

2O + 2 H+ + 2 e− → N

2 + H2O (Nitrous oxide reductase)

The complete process can be expressed as a net balanced redox reaction, where nitrate (NO3−) gets fully reduced to dinitrogen (N2):

- 2 NO3− + 10 e− + 12 H+ → N2 + 6 H2O

Conditions of denitrification

In nature, denitrification can take place in both terrestrial and marine ecosystems.[10] Typically, denitrification occurs in anoxic environments, where the concentration of dissolved and freely available oxygen is depleted. In these areas, nitrate (NO3−) or nitrite (NO

2−) can be used as a substitute terminal electron acceptor instead of oxygen (O2), a more energetically favourable electron acceptor. Terminal electron acceptor is a compound that gets reduced in the reaction by receiving electrons. Examples of anoxic environments can include soils,[11] groundwater,[12] wetlands, oil reservoirs,[13] poorly ventilated corners of the ocean and seafloor sediments.

Furthermore, denitrification can occur in oxic environments as well. High activity of denitrifiers can be observed in the intertidal zones, where the tidal cycles cause fluctuations of oxygen concentration in sandy coastal sediments.[14] For example, the bacterial species Paracoccus denitrificans engages in denitrification under both oxic and anoxic conditions simultaneously. Upon oxygen exposure, the bacteria is able to utilize nitrous oxide reductase, an enzyme that catalyzes the last step of denitrification.[15] Aerobic denitrifiers are mainly Gram-negative bacteria in the phylum Proteobacteria. Enzymes NapAB, NirS, NirK and NosZ are located in the periplasm, a wide space bordered by the cytoplasmic and the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria.[16]

Denitrification can lead to a condition called isotopic fractionation in the soil environment. The two stable isotopes of nitrogen, 14N and 15N are both found in the sediment profiles. The lighter isotope of nitrogen, 14N, is preferred during denitrification, leaving the heavier nitrogen isotope, 15N, in the residual matter. This selectivity leads to the enrichment of 14N in the biomass compared to 15N.[17] Moreover, the relative abundance of 14N can be analyzed to distinguish denitrification apart from other processes in nature.

Use in wastewater treatment

Denitrification is commonly used to remove nitrogen from sewage and municipal wastewater. It is also an instrumental process in constructed wetlands[18] and riparian zones[19] for the prevention of groundwater pollution with nitrate resulting from excessive agricultural or residential fertilizer usage.[20] Wood chip bioreactors have been studied since the 2000s and are effective in removing nitrate from agricultural run off[21] and even manure.[22]

Reduction under anoxic conditions can also occur through process called anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox):[23]

- NH4+ + NO2− → N2 + 2 H2O

In some wastewater treatment plants, compounds such as methanol, ethanol, acetate, glycerin, or proprietary products are added to the wastewater to provide a carbon and electron source for denitrifying bacteria.[24] The microbial ecology of such engineered denitrification processes is determined by the nature of the electron donor and the process operating conditions.[25][26] Denitrification processes are also used in the treatment of industrial wastewater.[27] Many denitrifying bioreactor types and designs are available commercially for the industrial applications, including Electro-Biochemical Reactors (EBRs), membrane bioreactors (MBRs), and moving bed bioreactors (MBBRs).

Aerobic denitrification, conducted by aerobic denitrifiers, may offer the potential to eliminate the need for separate tanks and reduce sludge yield. There are less stringent alkalinity requirements because alkalinity generated during denitrification can partly compensate for the alkalinity consumption in nitrification.[16]

See also

- Aerobic denitrification

- Anaerobic respiration

- Bioremediation

- Climate change

- Hypoxia (environmental)

- Nitrogen fixation

- Simultaneous nitrification-denitrification

References

- ↑ Carlson, C. A.; Ingraham, J. L. (1983). "Comparison of denitrification by Pseudomonas stutzeri, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Paracoccus denitrificans". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45 (4): 1247–1253. doi:10.1128/AEM.45.4.1247-1253.1983. PMC 242446. PMID 6407395.

- ↑ Baalsrud, K.; Baalsrud, Kjellrun S. (1954). "Studies on Thiobacillus denitrificans". Archiv für Mikrobiologie. 20 (1): 34–62. doi:10.1007/BF00412265. PMID 13139524. S2CID 22428082.

- 1 2 Zumft, W G (1997). "Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 61 (4): 533–616. doi:10.1128/.61.4.533-616.1997. PMC 232623. PMID 9409151.

- ↑ Atlas, R.M., Barthas, R. Microbial Ecology: Fundamentals and Applications. 3rd Ed. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing. ISBN 0-8053-0653-6

- ↑ Graf, Jon S.; Schorn, Sina; Kitzinger, Katharina; Ahmerkamp, Soeren; Woehle, Christian; Huettel, Bruno; Schubert, Carsten J.; Kuypers, Marcel M. M.; Milucka, Jana (3 March 2021). "Anaerobic endosymbiont generates energy for ciliate host by denitrification". Nature. 591 (7850): 445–450. Bibcode:2021Natur.591..445G. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03297-6. PMC 7969357. PMID 33658719.

- ↑ An, S.; Gardner, WS (2002). "Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) as a nitrogen link, versus denitrification as a sink in a shallow estuary (Laguna Madre/Baffin Bay, Texas)". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 237: 41–50. Bibcode:2002MEPS..237...41A. doi:10.3354/meps237041.

- ↑ Kuypers, MMM; Marchant, HK; Kartal, B (2011). "The Microbial Nitrogen-Cycling Network". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 1 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9. PMID 29398704. S2CID 3948918.

- ↑ Spanning, R., Delgado, M. and Richardson, D. (2005). "The Nitrogen Cycle: Denitrification and its Relationship to N2 Fixation". Nitrogen Fixation: Origins, Applications, and Research Progress. pp. 277–342. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3544-6_13. ISBN 978-1-4020-3542-5.

It is possible to encounter DNRA when your source of carbon is a fermentable substrate, as glucose, so if you wanna avoid DNRA use a non fermentable substrate

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Liu, X.; Tiquia, S. M.; Holguin, G.; Wu, L.; Nold, S. C.; Devol, A. H.; Luo, K.; Palumbo, A. V.; Tiedje, J. M.; Zhou, J. (2003). "Molecular Diversity of Denitrifying Genes in Continental Margin Sediments within the Oxygen-Deficient Zone off the Pacific Coast of Mexico". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 (6): 3549–3560. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.328.2951. doi:10.1128/aem.69.6.3549-3560.2003. PMC 161474. PMID 12788762.

- ↑ Seitzinger, S.; Harrison, J. A.; Bohlke, J. K.; Bouwman, A. F.; Lowrance, R.; Peterson, B.; Tobias, C.; Drecht, G. V. (2006). "Denitrification Across Landscapes and Waterscapes: A Synthesis". Ecological Applications. 16 (6): 2064–2090. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2064:dalawa]2.0.co;2. hdl:1912/4707. PMID 17205890.

- ↑ Scaglia, J.; Lensi, R.; Chalamet, A. (1985). "Relationship between photosynthesis and denitrification in planted soil". Plant and Soil. 84 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1007/BF02197865. S2CID 20602996.

- ↑ Korom, Scott F. (1992). "Natural Denitrification in the Saturated Zone: A Review". Water Resources Research. 28 (6): 1657–1668. Bibcode:1992WRR....28.1657K. doi:10.1029/92WR00252.

- ↑ Cornish Shartau, S. L.; Yurkiw, M.; Lin, S.; Grigoryan, A. A.; Lambo, A.; Park, H. S.; Lomans, B. P.; Van Der Biezen, E.; Jetten, M. S. M.; Voordouw, G. (2010). "Ammonium Concentrations in Produced Waters from a Mesothermic Oil Field Subjected to Nitrate Injection Decrease through Formation of Denitrifying Biomass and Anammox Activity". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 76 (15): 4977–4987. doi:10.1128/AEM.00596-10. PMC 2916462. PMID 20562276.

- ↑ Merchant; et al. (2017). "Denitrifying community in coastal sediments performs aerobic and anaerobic respiration simultaneously". The ISME Journal. 11 (8): 1799–1812. doi:10.1038/ismej.2017.51. PMC 5520038. PMID 28463234.

- ↑ Qu; et al. (2016). "Transcriptional and metabolic regulation of denitrification in Paracoccus denitrificans allows low but significant activity of nitrous oxide reductase under oxic conditions". Environmental Microbiology. 18 (9): 2951–63. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13128. PMID 26568281.

- 1 2 Ji, Bin; Yang, Kai; Zhu, Lei; Jiang, Yu; Wang, Hongyu; Zhou, Jun; Zhang, Huining (2015). "Aerobic denitrification: A review of important advances of the last 30 years". Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering. 20 (4): 643–651. doi:10.1007/s12257-015-0009-0. S2CID 85744076.

- ↑ Dähnke K.; Thamdrup B. (2013). "Nitrogen isotope dynamics and fractionation during sedimentary denitrification in Boknis Eck, Baltic Sea". Biogeosciences. 10 (5): 3079–3088. Bibcode:2013BGeo...10.3079D. doi:10.5194/bg-10-3079-2013 – via Copernicus Publications.

- ↑ Bachand, P. A. M.; Horne, A. J. (1999). "Denitrification in constructed free-water surface wetlands: II. Effects of vegetation and temperature". Ecological Engineering. 14 (1–2): 17–32. doi:10.1016/s0925-8574(99)00017-8.

- ↑ Martin, T. L.; Kaushik, N. K.; Trevors, J. T.; Whiteley, H. R. (1999). "Review: Denitrification in temperate climate riparian zones". Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 111: 171–186. Bibcode:1999WASP..111..171M. doi:10.1023/a:1005015400607. S2CID 96384737.

- ↑ Mulvaney, R. L.; Khan, S. A.; Mulvaney, C. S. (1997). "Nitrogen fertilizers promote denitrification". Biology and Fertility of Soils. 24 (2): 211–220. doi:10.1007/s003740050233. S2CID 18518.

- ↑ Ghane, E; Fausey, NR; Brown, LC (Jan 2015). "Modeling nitrate removal in a denitrification bed". Water Res. 71C: 294–305. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2014.10.039. PMID 25638338. (subscription required)

- ↑ Carney KN, Rodgers M; Lawlor, PG; Zhan, X (2013). "Treatment of separated piggery anaerobic digestate liquid using woodchip biofilters". Environ Technology. 34 (5–8): 663–70. doi:10.1080/09593330.2012.710408. PMID 23837316. S2CID 10397713. (subscription required)

- ↑ Dalsgaard, T.; Thamdrup, B.; Canfield, D. E. (2005). "Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) in the marine environment". Research in Microbiology. 156 (4): 457–464. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2005.01.011. PMID 15862442.

- ↑ Chen, K.-C.; Lin, Y.-F. (1993). "The relationship between denitrifying bacteria and methanogenic bacteria in a mixed culture system of acclimated sludges". Water Research. 27 (12): 1749–1759. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(93)90113-v.

- ↑ Baytshtok, Vladimir; Lu, Huijie; Park, Hongkeun; Kim, Sungpyo; Yu, Ran; Chandran, Kartik (2009-04-15). "Impact of varying electron donors on the molecular microbial ecology and biokinetics of methylotrophic denitrifying bacteria". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 102 (6): 1527–1536. doi:10.1002/bit.22213. PMID 19097144. S2CID 6445650.

- ↑ Lu, Huijie; Chandran, Kartik; Stensel, David (November 2014). "Microbial ecology of denitrification in biological wastewater treatment". Water Research. 64: 237–254. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2014.06.042. PMID 25078442.

- ↑ Constantin, H.; Fick, M. (1997). "Influence of C-sources on the denitrification rate of a high-nitrate concentrated industrial wastewater". Water Research. 31 (3): 583–589. doi:10.1016/s0043-1354(96)00268-0.