Endocardium

| Endocardium | |

|---|---|

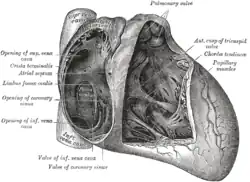

Interior of right side of heart | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Endocardium |

| MeSH | D004699 |

| TA98 | A12.1.05.001 |

| TA2 | 3962 |

| FMA | 7280 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

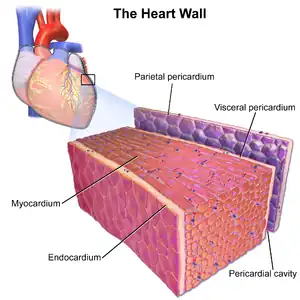

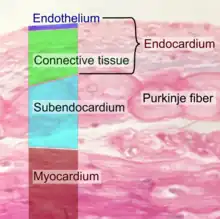

The endocardium is the innermost layer of tissue that lines the chambers of the heart. Its cells are embryologically and biologically similar to the endothelial cells that line blood vessels. The endocardium also provides protection to the valves and heart chambers.

The endocardium underlies the much more voluminous myocardium, the muscular tissue responsible for the contraction of the heart. The outer layer of the heart is termed epicardium and the heart is surrounded by a small amount of fluid enclosed by a fibrous sac called the pericardium.

Function

The endocardium, which is primarily made up of endothelial cells, controls myocardial function. This modulating role is separate from the homeometric and heterometric regulatory mechanisms that control myocardial contractility. Moreover, the endothelium of the myocardial (heart muscle) capillaries, which is also closely appositioned to the cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells), is involved in this modulatory role. Thus, the cardiac endothelium (both the endocardial endothelium and the endothelium of the myocardial capillaries) controls the development of the heart in the embryo as well as in the adult, for example during hypertrophy. Additionally, the contractility and electrophysiological environment of the cardiomyocyte are regulated by the cardiac endothelium.

The endocardial endothelium may also act as a kind of blood–heart barrier (analogous to the blood–brain barrier), thus controlling the ionic composition of the extracellular fluid in which the cardiomyocytes bathe.

Clinical significance

In myocardial infarction, ischemia of the myocardium starts at the endocardium[1] and might extend up to the epicardium, disrupting the entire heart wall ("transmural" infarction). Less extensive infarctions are often "subendocardial" and do not affect the epicardium. In the acute setting, subendocardial infarctions are more dangerous than transmural infarctions because they create an area of dead tissue surrounded by a boundary region of damaged myocytes. This damaged region will conduct impulses more slowly, resulting in irregular rhythms. The damaged region may enlarge or extend and become more life-threatening. In the chronic setting, transmural infarctions are more dangerous due to the greater amount of muscular damage and the development of scar tissue leading to impaired systolic contractility, impaired diastolic relaxation, and increased risk for rupture and thrombus formation.

During depolarization the impulse is carried from endocardium to epicardium, and during repolarization the impulse moves from epicardium to endocardium. In infective endocarditis, the endocardium (especially the endocardium lining the heart valves) is affected by bacteria.

References

- ↑ Algranati, Dotan; Kassab, Ghassan; Lanir, Yoram (2010). "Why is the subendocardium more vulnerable to ischemia? A new paradigm". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 300 (3): H1090–H1100. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00473.2010. PMC 3064294. PMID 21169398.

External links

- Histology image: 64_06 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "Heart and AV valve" (atrial endocardium)

- Histology image: 64_07 at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center - "Heart and AV valve" (ventricular endocardium)