Gong farmer

Gong farmer (also gongfermor, gongfermour, gong-fayer, gong-fower or gong scourer) was a term that entered use in Tudor England to describe someone who dug out and removed human excrement from privies and cesspits. The word "gong" was used for both a privy and its contents. As the work was considered unclean and off-putting to the public, gong farmers were only allowed to work at night, hence they were sometimes known as nightmen. The waste they collected, known as night soil, had to be taken outside the city or town boundary or to official dumps for disposal.

Fewer and fewer cesspits needed to be dug out as more modern sewage disposal systems, such as pail closets and water closets, became increasingly widespread in 19th-century England. The job of emptying cesspits today is usually carried out mechanically using suction, by specialised tankers called vacuum trucks.

Early sewage arrangements

"Gong" is derived from Old English: gang, which means "to go".[1][2] Towns usually provided public latrines, known as houses of easement,[3] but numbers were limited: in London towards the end of the 14th century, for instance, there were only 16 for a population of 30,000.[4] Local regulations were introduced to control the placement and construction of private latrines. Cesspits were often placed under cellar floors or in the yard of a house. Some had wooden chutes to carry excrement from the upper floors to the cesspit, sometimes flushed by rainwater.[5] Cesspits were not watertight, allowing the liquid waste to drain away and leaving only the solids to be collected.[3]

A foul odour from cesspits was a continual problem, and the accumulation of solid waste meant that they had to be cleaned out every two years or so. It was the job of the gong farmers to dig them out and remove the excrement. In the late 15th century they charged two shillings per ton of waste removed.[5]

Working conditions

Despite being well-rewarded, the role of gong farmer was considered by historians on television series The Worst Jobs in History to be one of the worst of the Tudor period.[6] Those employed at Hampton Court during the time of Queen Elizabeth I, for instance, were paid sixpence a day—a good living for the period—but the working life of a gong farmer was "spent up to his knees, waist, even neck in human ordure".[7] They were only allowed to work at night, between 9pm and 5am.[nb 1] They were permitted to live only in specified areas, and were sometimes overcome by asphyxiation from the noxious fumes produced by human excrement.

Gong farmers usually employed a couple of young boys to lift the full buckets of ordure out of the pit and to work in confined spaces.[7]

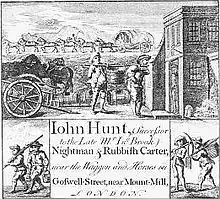

After being dug out, the solid waste was removed in large barrels or pipes, which were loaded onto a horse-drawn cart.[7] As privies spread to the residences of ordinary citizens they were often built in backyards with rear access or alleyways, to avoid the need to carry barrels of waste through the house to the street. Much of what is known about London's privies during the 17th and 18th century comes from witness statements describing what had been discovered among the human excrement, such as the corpses of unwanted infants.[3]

All of the human waste had to be removed from the town or city where it was collected, either by spreading it on common land or by transporting it to laystalls, which were usually on the edges of town.[8] Much of the contents of London's cess pits was taken to dumps on the banks of the River Thames such as the appropriately named Dung Wharf—later the site of the Mermaid Theatre[9]—from which it was transported by barge to be used as fertiliser on fields or market gardens.[8] Some of the dumps became quite massive; Mount Pleasant in present-day Clerkenwell, London, occupied an area of 7.5 acres (3.0 ha) by 1780.[10]

The penalties for not disposing of waste in the approved manner could be harsh. One London gong farmer who poured effluent down a drain was put in one of his own pipes filled up to his neck with filth, before being publicly displayed in Golden Lane with a sign detailing his crime.[11]

Later developments

From the early 17th century onwards the larger towns and cities began to employ scavengers, as they became known, to remove human waste from the streets. Much of this waste came from overflowing privies and dunghills, or from chamber pots emptied into the streets from upstairs windows. By 1615 the town of Manchester was employing nineteen under-scavengers, or rakers, managed by two scavengers.[8]

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ gang, n.1 ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, 1989, retrieved 30 December 2009

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - 1 2 gong, n.1 ((subscription or UK public library membership required)), Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, 1989, retrieved 30 December 2009

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - 1 2 3 Cockayne 2007, p. 143

- ↑ Galloway 2003, p. 78

- 1 2 Hanawalt 1995, pp. 28–29

- ↑ "The Worst Jobs in History". Series One. Channel 4.

- 1 2 3 Robinson 2004, p. 88

- 1 2 3 Cockayne 2007, p. 184

- ↑ Cockayne 2007, p. 190

- ↑ Cockayne 2007, p. 191

- ↑ Robinson 2004, pp. 89–90

Bibliography

- Cockayne, Emily (2007), Hubbub: Filth, Noise and Stench in England 1600–1770, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-13756-9

- Galloway, Priscilla (2003), Archers, Alchemists, and 98 Other Medieval Jobs You Might Have Loved or Loathed (Jobs in History), Annick Press, ISBN 978-1-55037-810-8

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. (1995), Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Childhood in History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-509384-1

- Robinson, Tony (2004), The Worst Jobs in History, Channel 4, ISBN 978-0-7522-1533-4