Haemophilus influenzae infection

| Haemophilus influenzae infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Haemophilus influenza disease[1] | |

| |

| Haemophilus influenzae meningitis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Types | Ear infections, bronchitis, pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, epiglottis, skin infections, infectious arthritis.[2] |

| Causes | Haemophilus influenzae[1] |

| Risk factors | Weak immune system, HIV, sickle cell disease, no spleen[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Testing blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid,[4] chest X-ray[2] |

| Prevention |

|

| Treatment | Antibiotics[4] |

| Medication |

|

| Prognosis | Good if early treatment, Hib meningitis (5% mortality)[2] |

| Frequency | 3 million (serious cases)[6] |

| Deaths | 400,000 deaths per year[6] |

Haemophilus influenzae infection, also known as Haemophilus influenzae disease is a vaccine-preventable disease caused by the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae.[1] Diseases in this group include ear infections, bronchitis, pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, epiglottitis, skin infections and infectious arthritis.[2] All of these infections can cause a fever.[7] Other symptoms depend on the part of the body that is infected; cough and breathlessness in pneumonia; tiredness and confusion in sepsis; headache, stiff neck, and photophobia in meningitis.[7]

H. influenzae type b (Hib) causes severe H. influenzae disease.[3] It is spread by breathing in or having contact with respiratory droplets from either a sick or well person who carries H. influenza in their nose or throat.[3] Children under the age of five years, adults over 65 years, people from Alaska, American Indians and people with weakened immune systems, HIV, sickle cell disease, and no spleen, are at higher risk of disease.[3]

Diagnosis is by isolating the organism usually by testing of blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid.[4] Other tests may include chest X-ray.[2] A safe and effective vaccine against Hib has been available since the 1980s.[5] Close contacts may benefit from antibiotics to prevent being infected; typically 4 days of rifampin at a dose of 20mg/kg/day (max. 600mg/day).[2][8] Breast feeding has been shown to be protective.[2] Treatment is with antibiotics and correcting oxygen and blood pressure, with attention to wound care.[4] Cefotaxime or ceftriaxone are generally administered in Hib meningitis.[2] Adding dexamethasone in children with Hib meningitis may reduce chance of developing hearing complications.[2] For other Hib infections, cefuroxime may be used.[2] Collections of pus may need surgical draining.[2] Early treatment usually leads to full recovery.[2] However, 1 in 20 people with Hib meningitis may die, and of those that survive, up to 30% may have long term complications such as hearing loss, visual loss and developmental delay.[2]

In groups that are not immunised, Hib is responsible for 95% of all severe H. influenzae infections.[6] Globally, Hib causes 3 million episodes of serious disease and 400,000 deaths a year.[6] In countries where the vaccine is part of an immunization programme, serious H. influenzae disease is rare.[9] Prior to the introduction of vaccination, it was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in children, particularly those under the age of 3 years, in who 4% carried the bacteria in their nose and throat without knowing.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Haemophilus influenzae disease is any infection caused by the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae,[1] Diseases in this group include ear infections, bronchitis, pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, epiglottitis, skin infections and infectious arthritis.[2]

There is typically a fever.[7] Other signs and symptoms depend on the part of the body that is infected.[7]

Epiglottitis as seen during endoscopy

Epiglottitis as seen during endoscopy Endophthalmitis caused by H. influenzae

Endophthalmitis caused by H. influenzae

Cause

H. influenzae type b (Hib) causes severe H. influenzae disease.[6] It is spread by breathing in or having contact with respiratory droplets from either a sick or well person who carries H. influenza in their nose or throat.[3]

Risk factors

Children under the age of five years, adults over 65 years, people from Alaska, American Indians and people with weakened immune systems, HIV, sickle cell disease and no spleen, are at higher risk of H. influenzae disease.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually by laboratory testing.[4]

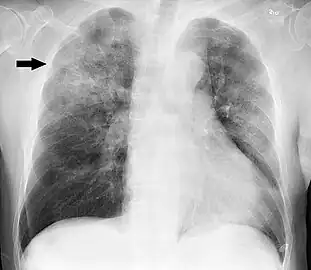

Chest X-ray in a case of COPD exacerbation where a nasopharyngeal swab detected Haemophilus influenzae: Opacities (on the patient's right side) can be seen in other types of pneumonia, as well.

Chest X-ray in a case of COPD exacerbation where a nasopharyngeal swab detected Haemophilus influenzae: Opacities (on the patient's right side) can be seen in other types of pneumonia, as well. Chest X-ray of a case of Haemophilus influenzae, presumably as a secondary infection from influenza. It shows patchy consolidations, mainly in the right upper lobe (arrow).

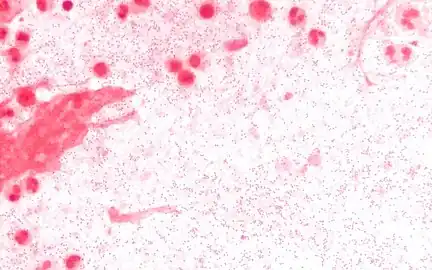

Chest X-ray of a case of Haemophilus influenzae, presumably as a secondary infection from influenza. It shows patchy consolidations, mainly in the right upper lobe (arrow). Sputum Gram stain at 1000x magnification. The sputum is from a person with Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia, and the Gram negative coccobacilli are visible with a background of neutrophils.

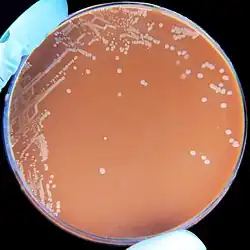

Sputum Gram stain at 1000x magnification. The sputum is from a person with Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia, and the Gram negative coccobacilli are visible with a background of neutrophils. H. influenzae on a chocolate agar plate

H. influenzae on a chocolate agar plate

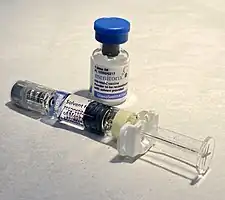

Prevention

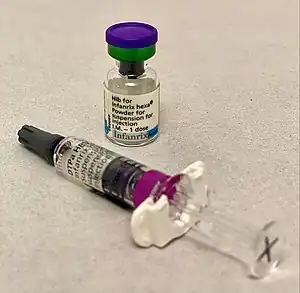

A vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae is safe and over 90% effective at preventing H. influenzae disease due to type b.[5]

Act-Hib

Act-Hib Infanrix hexa

Infanrix hexa Menitorix

Menitorix

Treatment

Treatment is with antibiotics and correcting oxygen and blood pressure, with attention to wound care.[4] In Hib meningitis, antibiotics found effective include cefotaxime and ceftriaxone.[2] For other Hib infections, cefuroxime may be used.[2]

Epidemiology

In groups that are not immunised, Hib is responsible for 95% of all severe H. influenzae infections.[6] Globally, Hib causes 3 million episodes of serious disease and 400,000 deaths per year.[6] In countries where the vaccine is part of an immunization programme, serious H. influenzae disease is rare.[9]

History

A safe and effective vaccine against Hib has been available since the 1980s.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "About Haemophilus influenzae | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Yeh, Sylvia H. (2022). "4. Haemophilus influenzae Type B". In Jong, Elaine C.; Stevens, Dennis L. (eds.). Netter's Infectious Diseases (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-0-323-71159-3. Archived from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Haemophilus influenzae: Causes and Transmission | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Haemophilus influenzae: Diagnosis and Treatment | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Heininger, Ulrich (2021). "19. Haemophilus influenza Type b (Hib) vaccines". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (2nd ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 195–206. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 2023-10-20. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Factsheet about Invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Symptoms of Haemophilus influenzae | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ "Preventing Haemophilus influenzae | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- 1 2 Barlow, Gavin; Irving, William L.; Moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 545. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2021-12-22.