Inner ear

| Inner ear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Artery | labyrinthine artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | auris interna |

| MeSH | D007758 |

| TA98 | A15.3.03.001 |

| TA2 | 6935 |

| FMA | 60909 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| This article is one of a series documenting the anatomy of the |

| Human ear |

|---|

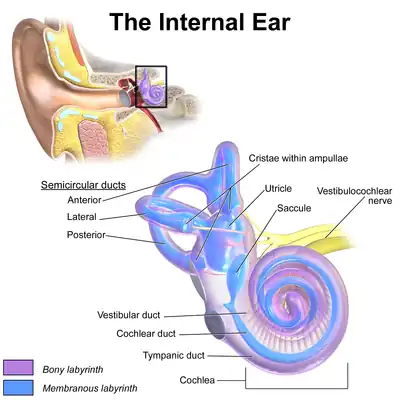

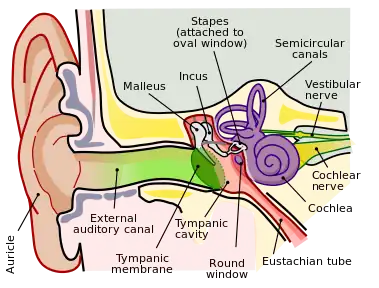

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance.[1] In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in the temporal bone of the skull with a system of passages comprising two main functional parts:[2]

- The cochlea, dedicated to hearing; converting sound pressure patterns from the outer ear into electrochemical impulses which are passed on to the brain via the auditory nerve.

- The vestibular system, dedicated to balance

The inner ear is found in all vertebrates, with substantial variations in form and function. The inner ear is innervated by the eighth cranial nerve in all vertebrates.

Structure

The labyrinth can be divided by layer or by region.

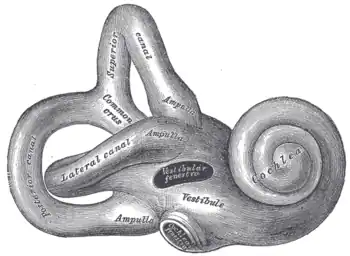

Bony and membranous labyrinths

The bony labyrinth, or osseous labyrinth, is the network of passages with bony walls lined with periosteum. The three major parts of the bony labyrinth are the vestibule of the ear, the semicircular canals, and the cochlea. The membranous labyrinth runs inside of the bony labyrinth, and creates three parallel fluid filled spaces. The two outer are filled with perilymph and the inner with endolymph.[3]

Vestibular and cochlear systems

In the middle ear, the energy of pressure waves is translated into mechanical vibrations by the three auditory ossicles. Pressure waves move the tympanic membrane which in turns moves the malleus, the first bone of the middle ear. The malleus articulates to incus which connects to the stapes. The footplate of the stapes connects to the oval window, the beginning of the inner ear. When the stapes presses on the oval window, it causes the perilymph, the liquid of the inner ear to move. The middle ear thus serves to convert the energy from sound pressure waves to a force upon the perilymph of the inner ear. The oval window has only approximately 1/18 the area of the tympanic membrane and thus produces a higher pressure. The cochlea propagates these mechanical signals as waves in the fluid and membranes and then converts them to nerve impulses which are transmitted to the brain.[4]

The vestibular system is the region of the inner ear where the semicircular canals converge, close to the cochlea. The vestibular system works with the visual system to keep objects in view when the head is moved. Joint and muscle receptors are also important in maintaining balance. The brain receives, interprets, and processes the information from all these systems to create the sensation of balance.

The vestibular system of the inner ear is responsible for the sensations of balance and motion. It uses the same kinds of fluids and detection cells (hair cells) as the cochlea uses, and sends information to the brain about the attitude, rotation, and linear motion of the head. The type of motion or attitude detected by a hair cell depends on its associated mechanical structures, such as the curved tube of a semicircular canal or the calcium carbonate crystals (otolith) of the saccule and utricle.

Development

The human inner ear develops during week 4 of embryonic development from the auditory placode, a thickening of the ectoderm which gives rise to the bipolar neurons of the cochlear and vestibular ganglions.[5] As the auditory placode invaginates towards the embryonic mesoderm, it forms the auditory vesicle or otocyst.

The auditory vesicle will give rise to the utricular and saccular components of the membranous labyrinth. They contain the sensory hair cells and otoliths of the macula of utricle and of the saccule, respectively, which respond to linear acceleration and the force of gravity. The utricular division of the auditory vesicle also responds to angular acceleration, as well as the endolymphatic sac and duct that connect the saccule and utricle.

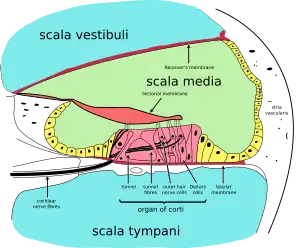

Beginning in the fifth week of development, the auditory vesicle also gives rise to the cochlear duct, which contains the spiral organ of Corti and the endolymph that accumulates in the membranous labyrinth.[6] The vestibular wall will separate the cochlear duct from the perilymphatic scala vestibuli, a cavity inside the cochlea. The basilar membrane separates the cochlear duct from the scala tympani, a cavity within the cochlear labyrinth. The lateral wall of the cochlear duct is formed by the spiral ligament and the stria vascularis, which produces the endolymph. The hair cells develop from the lateral and medial ridges of the cochlear duct, which together with the tectorial membrane make up the organ of Corti.[6]

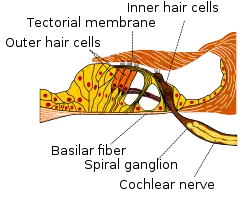

Microanatomy

Rosenthal's canal or the spiral canal of the cochlea is a section of the bony labyrinth of the inner ear that is approximately 30 mm long and makes 2¾ turns about the modiolus, the central axis of the cochlea that contains the spiral ganglion.

Specialized inner ear cell include: hair cells, pillar cells, Boettcher's cells, Claudius' cells, spiral ganglion neurons, and Deiters' cells (phalangeal cells).

The hair cells are the primary auditory receptor cells and they are also known as auditory sensory cells, acoustic hair cells, auditory cells or cells of Corti. The organ of Corti is lined with a single row of inner hair cells and three rows of outer hair cells. The hair cells have a hair bundle at the apical surface of the cell. The hair bundle consists of an array of actin-based stereocilia. Each stereocilium inserts as a rootlet into a dense filamentous actin mesh known as the cuticular plate. Disruption of these bundles results in hearing impairments and balance defects.

Inner and outer pillar cells in the organ of Corti support hair cells. Outer pillar cells are unique because they are free standing cells which only contact adjacent cells at the bases and apices. Both types of pillar cell have thousands of cross linked microtubules and actin filaments in parallel orientation. They provide mechanical coupling between the basement membrane and the mechanoreceptors on the hair cells.

Boettcher's cells are found in the organ of Corti where they are present only in the lower turn of the cochlea. They lie on the basilar membrane beneath Claudius' cells and are organized in rows, the number of which varies between species. The cells interdigitate with each other, and project microvilli into the intercellular space. They are supporting cells for the auditory hair cells in the organ of Corti. They are named after German pathologist Arthur Böttcher (1831-1889).

Claudius' cells are found in the organ of Corti located above rows of Boettcher's cells. Like Boettcher's cells, they are considered supporting cells for the auditory hair cells in the organ of Corti. They contain a variety of aquaporin water channels and appear to be involved in ion transport. They also play a role in sealing off endolymphatic spaces. They are named after the German anatomist Friedrich Matthias Claudius (1822-1869).

Deiters' cells (phalangeal cells) are a type of neuroglial cell found in the organ of Corti and organised in one row of inner phalangeal cells and three rows of outer phalangeal cells. They are the supporting cells of the hair cell area within the cochlea. They are named after the German pathologist Otto Deiters (1834-1863) who described them.

Hensen's cells are high columnar cells that are directly adjacent to the third row of Deiters’ cells.

Hensen's stripe is the section of the tectorial membrane above the inner hair cell.

Nuel's spaces refer to the fluid-filled spaces between the outer pillar cells and adjacent hair cells and also the spaces between the outer hair cells.

Hardesty's membrane is the layer of the tectoria closest to the reticular lamina and overlying the outer hair cell region.

Reissner's membrane is composed of two cell layers and separates the scala media from the scala vestibuli.

Huschke's teeth are the tooth-shaped ridges on the spiral limbus that are in contact with the tectoria and separated by interdental cells.

Blood supply

The bony labyrinth receives its blood supply from three arteries: 1- Anterior tympanic branch (from maxillary artery). 2- Petrosal branch (from middle meningeal artery). 3- Stylomastoid branch (from posterior auricular artery). The membranous labyrinth is supplied by the labyrinthine artery. Venous drainage of the inner ear is through the labyrinthine vein, which empties into the sigmoid sinus or inferior petrosal sinus.

Function

Neurons within the ear respond to simple tones, and the brain serves to process other increasingly complex sounds. An average adult is typically able to detect sounds ranging between 20 and 20,000 Hz. The ability to detect higher pitch sounds decreases in older humans.

The human ear has evolved with two basic tools to encode sound waves; each is separate in detecting high and low-frequency sounds. Georg von Békésy (1899-1972) employed the use of a microscope in order to examine the basilar membrane located within the inner-ear of cadavers. He found that movement of the basilar membrane resembles that of a traveling wave; the shape of which varies based on the frequency of the pitch. In low-frequency sounds, the tip (apex) of the membrane moves the most, while in high-frequency sounds, the base of the membrane moves most.[7]

Disorders

Interference with or infection of the labyrinth can result in a syndrome of ailments called labyrinthitis. The symptoms of labyrinthitis include temporary nausea, disorientation, vertigo, and dizziness. Labyrinthitis can be caused by viral infections, bacterial infections, or physical blockage of the inner ear.[8][9]

Another condition has come to be known as autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED). It is characterized by idiopathic, rapidly progressive, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. It is a fairly rare disorder while at the same time, a lack of proper diagnostic testing has meant that its precise incidence cannot be determined.[10]

Other animals

Birds have an auditory system similar to that of mammals, including a cochlea. Reptiles, amphibians, and fish do not have cochleas but hear with simpler auditory organs or vestibular organs, which generally detect lower-frequency sounds than the cochlea. The cochlea of birds is similar to that of crocodiles, consisting of a short, slightly curved bony tube within which lies the basilar membrane with its sensory structures.[11]

Cochlear system

In reptiles, sound is transmitted to the inner ear by the stapes (stirrup) bone of the middle ear. This is pressed against the oval window, a membrane-covered opening on the surface of the vestibule. From here, sound waves are conducted through a short perilymphatic duct to a second opening, the round window, which equalizes pressure, allowing the incompressible fluid to move freely. Running parallel with the perilymphatic duct is a separate blind-ending duct, the lagena, filled with endolymph. The lagena is separated from the perilymphatic duct by a basilar membrane, and contains the sensory hair cells that finally translate the vibrations in the fluid into nerve signals. It is attached at one end to the saccule.[12]

In most reptiles the perilymphatic duct and lagena are relatively short, and the sensory cells are confined to a small basilar papilla lying between them. However, in mammals, birds, and crocodilians, these structures become much larger and somewhat more complicated. In birds, crocodilians, and monotremes, the ducts are simply extended, together forming an elongated, more or less straight, tube. The endolymphatic duct is wrapped in a simple loop around the lagena, with the basilar membrane lying along one side. The first half of the duct is now referred to as the scala vestibuli, while the second half, which includes the basilar membrane, is called the scala tympani. As a result of this increase in length, the basilar membrane and papilla are both extended, with the latter developing into the organ of Corti, while the lagena is now called the cochlear duct. All of these structures together constitute the cochlea.[12]

In therian mammals, the lagena is extended still further, becoming a coiled structure (cochlea) in order to accommodate its length within the head. The organ of Corti also has a more complex structure in mammals than it does in other amniotes.[12]

The arrangement of the inner ear in living amphibians is, in most respects, similar to that of reptiles. However, they often lack a basilar papilla, having instead an entirely separate set of sensory cells at the upper edge of the saccule, referred to as the papilla amphibiorum, which appear to have the same function.[12]

Although many fish are capable of hearing, the lagena is, at best, a short diverticulum of the saccule, and appears to have no role in sensation of sound. Various clusters of hair cells within the inner ear may instead be responsible; for example, bony fish contain a sensory cluster called the macula neglecta in the utricle that may have this function. Although fish have neither an outer nor a middle ear, sound may still be transmitted to the inner ear through the bones of the skull, or by the swim bladder, parts of which often lie close by in the body.[12]

Vestibular system

By comparison with the cochlear system, the vestibular system varies relatively little between the various groups of jawed vertebrates. The central part of the system consists of two chambers, the saccule and utricle, each of which includes one or two small clusters of sensory hair cells. All jawed vertebrates also possess three semicircular canals arising from the utricle, each with an ampulla containing sensory cells at one end.[12]

An endolymphatic duct runs from the saccule up through the head and ending close to the brain. In cartilaginous fish, this duct actually opens onto the top of the head, and in some teleosts, it is simply blind-ending. In all other species, however, it ends in an endolymphatic sac. In many reptiles, fish, and amphibians this sac may reach considerable size. In amphibians the sacs from either side may fuse into a single structure, which often extends down the length of the body, parallel with the spinal canal.[12]

The primitive lampreys and hagfish, however, have a simpler system. The inner ear in these species consists of a single vestibular chamber, although in lampreys, this is associated with a series of sacs lined by cilia. Lampreys have only two semicircular canals, with the horizontal canal being absent, while hagfish have only a single, vertical, canal.[12]

Equilibrium

The inner ear is primarily responsible for balance, equilibrium and orientation in three-dimensional space. The inner ear can detect both static and dynamic equilibrium. Three semicircular ducts and two chambers, which contain the saccule and utricle, enable the body to detect any deviation from equilibrium. The macula sacculi detects vertical acceleration while the macula utriculi is responsible for horizontal acceleration. These microscopic structures possess stereocilia and one kinocilium which are located within the gelatinous otolithic membrane. The membrane is further weighted with otoliths. Movement of the stereocilia and kinocilium enable the hair cells of the saccula and utricle to detect motion. The semicircular ducts are responsible for detecting rotational movement.[13]

Additional images

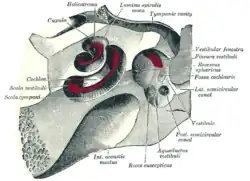

Ear labyrinth

Ear labyrinth Inner ear

Inner ear Temporal bone

Temporal bone Right human membranous labyrinth, removed from its bony enclosure and viewed from the antero-lateral aspect

Right human membranous labyrinth, removed from its bony enclosure and viewed from the antero-lateral aspect

See also

- Ear

- Hearing

- Middle ear

- Outer ear

- Tip link

References

- ↑ Torres, M., Giráldez, F. (1998) The development of the vertebrate inner ear. Mechanisms of Development 71 (1-2) pg 5-21

- ↑ J.M. Wolfe et al. (2009). Sensation & Perception. 2nd ed. Sunderland: Sinauer Associated Inc

- ↑ Rask-Andersen, Helge; Liu, Wei; Erixon, Elsa; Kinnefors, Anders; Pfaller, Kristian; Schrott-Fischer, Annelies; Glueckert, Rudolf (November 2012). "Human Cochlea: Anatomical Characteristics and their Relevance for Cochlear Implantation". The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 295 (11): 1791–1811. doi:10.1002/ar.22599. PMID 23044521. S2CID 25472441.

- ↑ Jan Schnupp, Israel Nelken and Andrew King (2011). Auditory Neuroscience. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-11318-2. Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ↑ Hyman, Libbie Henrietta (1992). Hyman's comparative vertebrate anatomy (3 ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 634. ISBN 0-226-87013-8. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- 1 2 Brauer, Philip R. (2003). Human embryology: the ultimate USMLE step 1 review. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 61. ISBN 1-56053-561-X. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ Schacter, Daniel (2012). Psychology. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1464135606.

- ↑ Labyrinthine dysfunction during diving. 1st Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. Vol. UHMS Publication Number WS6-15-74. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. 1973. p. 11. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ Kennedy RS (March 1974). "General history of vestibular disorders in diving". Undersea Biomedical Research. 1 (1): 73–81. PMID 4619861. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- ↑ Ruckenstein, M. J. (2004). "Autoimmune Inner Ear Disease". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 12(5), pp. 426-430.

- ↑ "Bird cochlea".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 476–489. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ Anatomy & Physiology The Unity of Form and Function. N.p.: McGraw-Hill College, 2011. Print.

- Ruckenstein, M. J. (2004). "Autoimmune Inner Ear Disease". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 12(5), pp. 426–430.

- Saladin, Anatomy and Physiology 6th ed., print

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, "The Middle Ear",

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inner ear. |

- Anatomy photo:30:05-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center