Mini–mental state examination

| Mini–mental state examination | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Folstein test |

| Purpose | measure cognitive impairment |

The mini–mental state examination (MMSE) or Folstein test is a 30-point questionnaire that is used extensively in clinical and research settings to measure cognitive impairment.[1][2] It is commonly used in medicine and allied health to screen for dementia. It is also used to estimate the severity and progression of cognitive impairment and to follow the course of cognitive changes in an individual over time; thus making it an effective way to document an individual's response to treatment. The MMSE's purpose has been not, on its own, to provide a diagnosis for any particular nosological entity.[3]

Administration of the test takes between 5 and 10 minutes and examines functions including registration (repeating named prompts), attention and calculation, recall, language, ability to follow simple commands and orientation.[4] It was originally introduced by Folstein et al. in 1975, in order to differentiate organic from functional psychiatric patients[5][6] but is very similar to, or even directly incorporates, tests which were in use previous to its publication.[7][8][9] This test is not a mental status examination. The standard MMSE form which is currently published by Psychological Assessment Resources is based on its original 1975 conceptualization, with minor subsequent modifications by the authors.

Advantages to the MMSE include requiring no specialized equipment or training for administration, and has both validity and reliability for the diagnosis and longitudinal assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Due to its short administration period and ease of use, it is useful for cognitive assessment in the clinician's office space or at the bedside.[10] Disadvantages to the utilization of the MMSE is that it is affected by demographic factors; age and education exert the greatest effect. The most frequently noted disadvantage of the MMSE relates to its lack of sensitivity to mild cognitive impairment and its failure to adequately discriminate patients with mild Alzheimer's disease from normal patients. The MMSE has also received criticism regarding its insensitivity to progressive changes occurring with severe Alzheimer's disease. The content of the MMSE is highly verbal, lacking sufficient items to adequately measure visuospatial and/or constructional praxis. Hence, its utility in detecting impairment caused by focal lesions is uncertain.[11]

Other tests are also used, such as the Hodkinson[12] abbreviated mental test score (1972), Geriatric Mental State Examination (GMS),[13] or the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition, bedside tests such as the 4AT (which also assesses for delirium), and computerised tests such as CoPs[14] and Mental Attributes Profiling System,[15] as well as longer formal tests for deeper analysis of specific deficits.

Test features

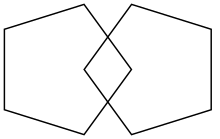

The MMSE test includes simple questions and problems in a number of areas: the time and place of the test, repeating lists of words, arithmetic such as the serial sevens, language use and comprehension, and basic motor skills. For example, one question, derived from the older Bender-Gestalt Test, asks to copy a drawing of two pentagons (shown on the right or above).[5]

A version of the MMSE questionnaire can be found on the British Columbia Ministry of Health website.[16]

Although consistent application of identical questions increases the reliability of comparisons made using the scale, the test can be customized (for example, for use on patients that are blind or partially immobilized.) Also, some have questioned the use of the test on the deaf.[17] However, the number of points assigned per category is usually consistent:

| Category | Possible points | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation to time | 5 | From broadest to most narrow. Orientation to time has been correlated with future decline.[18] |

| Orientation to place | 5 | From broadest to most narrow. This is sometimes narrowed down to streets,[19] and sometimes to floor.[20] |

| Registration | 3 | Repeating named prompts |

| Attention and calculation | 5 | Serial sevens, or spelling "world" backwards.[21] It has been suggested that serial sevens may be more appropriate in a population where English is not the first language.[22] |

| Recall | 3 | Registration recall |

| Language | 2 | Naming a pencil and a watch |

| Repetition | 1 | Speaking back a phrase |

| Complex commands | 6 | Varies. Can involve drawing figure shown. |

Interpretations

Any score of 24 or more (out of 30) indicates a normal cognition. Below this, scores can indicate severe (≤9 points), moderate (10–18 points) or mild (19–23 points) cognitive impairment. The raw score may also need to be corrected for educational attainment and age.[23] Even a maximum score of 30 points can never rule out dementia and there is no strong evidence to support this examination as a stand-alone one-time test for identifying high risk individuals who are likely to develop Alzheimer's.[24] Low to very low scores may correlate closely with the presence of dementia, although other mental disorders can also lead to abnormal findings on MMSE testing. The presence of purely physical problems can also interfere with interpretation if not properly noted; for example, a patient may be physically unable to hear or read instructions properly or may have a motor deficit that affects writing and drawing skills.

In order to maximize the benefits of the MMSE the following recommendations from Tombaugh and McIntyre (1992) should be employed:

- The MMSE should be used as a screening device for cognitive impairment or a diagnostic adjunct in which a low score indicates the need for further evaluation. It should not serve as the sole criterion for diagnosing dementia or to differentiate between various forms of dementia.[24] However, the MMSE scores may be used to classify the severity of cognitive impairment or to document serial change in dementia patients.

- The following four cut-off levels should be employed to classify the severity of cognitive impairment: no cognitive impairment 24–30; mild cognitive impairment 19–23; moderate cognitive impairment 10–18; and severe cognitive impairment ≤9.

- The MMSE should not be used clinically unless the person has at least a grade-eight education and is fluent in English. While this recommendation does not discount the possibility that future research may show that number of years of education constitutes a risk factor for dementia, it does acknowledge the weight of evidence showing that low educational levels substantially increase the likelihood of misclassifying normal subjects as cognitively impaired.

- Serial sevens and WORLD should not be considered equivalent items. Both items should be administered and the higher of the two should be used. In scoring serial sevens, each number must be independently compared to the prior number to ensure that a single mistake is not unduly penalized. WORLD should be spelled forward (and corrected) prior to spelling it backward.

- The words "apple", "penny", and "table" should be used for registration and recall. If necessary, the words may be administered up to three times in order to obtain perfect registration, but the score is based on the first trial.

- The "county" and "where are you" orientation to place questions should be modified: the name of the county where a person lives should be asked rather than the county of the testing site, and the name of the street where the individual lives should be asked rather than the name of the floor where the testing is taking place.

The MMSE may help differentiate different types of dementias. People with Alzheimer's disease may score significantly lower on orientation to time and place as well as recall, compared to those who have dementia with Lewy bodies, vascular dementia, or Parkinson's disease dementia.[25][26][27]

Copyright issues

The MMSE was first published in 1975 as an appendix to an article written by Marshal F. Folstein, Susan Folstein, and Paul R. McHugh.[5] It was published in Volume 12 of the Journal of Psychiatric Research, published by Pergamon Press. While the MMSE was attached as an appendix to the article, the copyright ownership of the MMSE (to the extent that it contains copyrightable content[28]) remained with the three authors. Pergamon Press was subsequently taken over by Elsevier, who also took over copyright of the Journal of Psychiatric Research.[29]

The authors later transferred all their intellectual property rights, including the copyright of the MMSE, to MiniMental registering the transfer with the U.S. Copyright Office on June 8, 2000.[30] In March 2001, MiniMental entered into an exclusive agreement with Psychological Assessment Resources granting PAR the exclusive rights to publish, license, and manage all intellectual property rights to the MMSE in all media and languages in the world.[31] Despite the many free versions of the test that are available on the internet, PAR claims that the official version is copyrighted and must be ordered only through it.[32][33] At least one legal expert has claimed that PAR's copyright claims are weak.[28] The enforcement of copyright on the MMSE has been compared to the phenomenon of "stealth" or "submarine" patents, in which a patent applicant waited until an invention gained widespread popularity before allowing the patent to issue, and only then commenced enforcement. Such applications are no longer possible, given changes in patent law.[32] The enforcement of the copyright has led to researchers looking for alternative strategies in assessing cognition.[34]

PAR have also asserted their copyright against an alternative diagnostic test, "Sweet 16", which was designed to avoid the copyright issues surrounding the MMSE. Sweet 16 was a 16-item assessment developed and validated by Tamara Fong and published in March 2011; like the MMSE it included orientation and three-object recall. Assertion of copyright forced the removal of this test from the Internet.[35]

Editions

In February 2010, PAR released a second edition of the MMSE; 10 foreign language translations (French, German, Dutch, Spanish for the US, Spanish for Latin America, European Spanish, Hindi, Russian, Italian, and Simplified Chinese) were also created.[36]

See also

- Abbreviated mental test score (AMTS)

- Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (ACE)

- Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE)

- Mental status examination (MSE)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

- NIH stroke scale (NIHSS)

- Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam (SLUMS)

- Self-administered Gerocognitive Examination (SAGE)

References

- ↑ Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué-Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, Pedraza OL, Bonfill Cosp X, Cullum S (July 2021). "Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 (7): CD010783. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub3. PMC 8406467. PMID 34313331.

- ↑ Pangman, VC; Sloan, J; Guse, L. (2000). "An Examination of Psychometric Properties of the Mini-Mental Status Examination and the Standardized Mini-Mental Status Examination: Implications for Clinical Practice". Applied Nursing Research. 13 (4): 209–213. doi:10.1053/apnr.2000.9231. PMID 11078787.

- ↑ Tombaugh, TN; McIntyre, NJ (1992). "The mini-mental Status Examination: A comprehensive Review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 40 (9): 922–935. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. PMID 1512391. S2CID 25169596.

- ↑ Tuijl, JP; Scholte, EM; de Craen, AJM; van der Mast, RC (2012). "Screening for cognitive impairment in older general hospital patients: comparison of the six-item cognitive test with the Mini-Mental Status Examination". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 27 (7): 755–762. doi:10.1002/gps.2776. PMID 21919059. S2CID 24638804.

- 1 2 3 Folstein, MF; Folstein, SE; McHugh, PR (1975). ""Mini-mental status". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 12 (3): 189–98. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. PMID 1202204. S2CID 25310196.

- ↑ Tombaugh, Tom N.; McIntyre, Nancy J. (1992). "The Mini Mental Status Examination: A comprehensive review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 40 (9): 922–935. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. PMID 1512391. S2CID 25169596.

- ↑ Eileen Withers; John Hinton (1971). "The Usefulness of the Clinical Tests of the Sensorium". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 119 (548): 9–18. doi:10.1192/bjp.119.548.9. PMID 5556665. S2CID 19654792.

- ↑ Jurgen Ruesch (1944). "Intellectual Impairment in Head Injuries". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 100 (4): 480–496. doi:10.1176/ajp.100.4.480.

- ↑ David Wechsler (1945). "A Standardized Memory Scale for Clinical Use". The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 19 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1080/00223980.1945.9917223.

- ↑ Harrell, LE; Marson, D; Chatterjee, A; Parrish, JA (2000). "The Severe Mini-Mental Status Examination: A New Neuropsychologic Instrument for the Bedside Assessment of Severely Impaired with Alzheimer's Disease". Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 14 (3): 168–175. doi:10.1097/00002093-200007000-00008. PMID 10994658. S2CID 10506318.

- ↑ Tomburgh; McIntyre (1992). "The Mini-Mental Status Examination: A comprehensive Review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 40 (9): 922–935. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. PMID 1512391. S2CID 25169596.

- ↑ Hodkinson, HM (1972). "Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly". Age and Ageing. 1 (4): 233–8. doi:10.1093/ageing/1.4.233. PMID 4669880.

- ↑ McWilliam, Christopher; Copeland, John R. M.; Dewey, Michael E.; Wood, Neil (February 2018). "The Geriatric Mental State (GMS) used in the community: replication studies of the computerized diagnosis AGECAT". Br. J. Psychiatry. 152 (2): 205–208. doi:10.1192/bjp.152.2.205. PMID 3048522. S2CID 19457831.

- ↑ CoPs

- ↑ Mental Attributes Profiling System

- ↑ "British Columbia Ministry of Health Standard MMSE (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013.

- ↑ Dean, PM; Feldman, DM; Morere, D; Morton, D (December 2009). "Clinical evaluation of the mini-mental status exam with culturally Deaf senior citizens". Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 24 (8): 753–60. doi:10.1093/arclin/acp077. PMID 19861331.

- ↑ Guerrero-Berroa E, Luo X, Schmeidler J, et al. (December 2009). "The MMSE orientation for time domain is a strong predictor of subsequent cognitive decline in the elderly". Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 24 (12): 1429–37. doi:10.1002/gps.2282. PMC 2919210. PMID 19382130.

- ↑ Morales LS, Flowers C, Gutierrez P, Kleinman M, Teresi JA; Flowers; Gutierrez; Kleinman; Teresi (November 2006). "Item and scale differential functioning of the Mini-Mental Status Exam assessed using the Differential Item and Test Functioning (DFIT) Framework". Medical Care. 44 (11 Suppl 3): S143–51. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000245141.70946.29. PMC 1661831. PMID 17060821.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "MMSE". Archived from the original on 2010-02-25. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ↑ Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Huff FJ, et al. (1990). "Serial sevens versus world backwards: a comparison of the two measures of attention from the MMSE". J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 3 (4): 203–7. doi:10.1177/089198879000300405. PMID 2073308. S2CID 23054498.

- ↑ Espino DV, Lichtenstein MJ, Palmer RF, Hazuda HP; Lichtenstein; Palmer; Hazuda (May 2004). "Evaluation of the mini-mental status examination's internal consistency in a community-based sample of Mexican-American and European-American elders: results from the San Antonio Longitudinal Study of Aging". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 52 (5): 822–7. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52226.x. PMID 15086669. S2CID 21220067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF; Anthony; Bassett; Folstein (May 1993). "Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental Status Examination by age and educational level". JAMA. 269 (18): 2386–91. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03500180078038. PMID 8479064.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Arevalo-Rodriguez, Ingrid; Smailagic, Nadja; Roqué-Figuls, Marta; Ciapponi, Agustín; Sanchez-Perez, Erick; Giannakou, Antri; Pedraza, Olga L.; Bonfill Cosp, Xavier; Cullum, Sarah (2021-07-27). "Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (7): CD010783. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8406467. PMID 34313331.

- ↑ Palmqvist, S; Hansson, O; Minthon, L; Londos, E (December 2009). "Practical suggestions on how to differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease with common cognitive tests". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 24 (12): 1405–12. doi:10.1002/gps.2277. PMID 19347836. S2CID 30099877.

- ↑ Jefferson, AL; Cosentino, SA; Ball, SK; Bogdanoff, B; Leopold, N; Kaplan, E; Libon, DJ (Summer 2002). "Errors produced on the mini-mental status examination and neuropsychological test performance in Alzheimer's disease, ischemic vascular dementia, and Parkinson's disease". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 14 (3): 311–20. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.14.3.311. PMID 12154156.

- ↑ Ala, TA; Hughes, LF; Kyrouac, GA; Ghobrial, MW; Elble, RJ (June 2002). "The Mini-Mental Status exam may help in the differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 17 (6): 503–9. doi:10.1002/gps.550. PMID 12112173. S2CID 19992084.

- 1 2 James Grimmelmann. "How Copyright Is Like Cognitive Impairment".

- ↑ "History of Elsevier" (PDF). Elsevier. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-17. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ↑ Folstein MF, Folstein SE; McHugh, PR (2000-06-08). Mini-mental status : a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Patent number TX0005228282

- ↑ U.S. Copyright Office record #2

- 1 2 Powsner S, Powsner D; Powsner (2005). "Cognition, copyright, and the classroom". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (3): 627–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.627-a. PMID 15741491.

- ↑ "Mini-Mental Status Examination. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc". Archived from the original on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2006-06-22.

- ↑ Holsinger T, Deveau J, Boustani M, Williams JW; Deveau; Boustani; Williams Jr (June 2007). "Does this patient have dementia?". JAMA. 297 (21): 2391–404. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2391. PMID 17551132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ John C. Newman, M.D.; Robin Feldman, J.D. (December 2011). "Copyright and Open Access at the Bedside". NEJM. 365 (26): 2447–2449. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1110652. PMID 22204721.

- ↑ PAR. "MMSE-2 home page". Retrieved 2010-10-29.