Arnica montana

| Arnica montana | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1897 illustration[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Arnica |

| Species: | A. montana |

| Binomial name | |

| Arnica montana L. | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Arnica montana, also known as wolf's bane, leopard's bane, mountain tobacco and mountain arnica,[3] is a moderately toxic European flowering plant in the daisy family Asteraceae. It is noted for its large yellow flower head. The names "wolf's bane" and "leopard's bane" are also used for another plant, aconitum, which is extremely poisonous.

Arnica montana is used as an herbal medicine for analgesic and anti-inflammatory purposes, but there is insufficient high-quality clinical evidence for such effects, and it is toxic when taken internally or applied to injured skin.[4]

Description

Arnica montana is a flowering plant about 18–60 cm (7.1–23.6 in) tall aromatic fragrant, herbaceous perennial. Its basal green ovate leaves with rounded tips are bright coloured and level to the ground. In addition, they are somewhat downy on their upper surface, veined and aggregated in rosettes. By contrast, the upper leaves are opposed, spear-shaped and smaller which is an exception within the Asteraceae. The chromosome number is 2n=38.

The flowering season is between May and August (Central Europe). The hairy flowers are composed of yellow disc florets in the center and orange-yellow ray florets at the external part. The achenes have a one-piece rough pappus which opens in dry conditions.[5][6] Arnica montana is a hemicryptophyte,[7] which helps the plant to survive the extreme overwintering condition of its habitat. In addition, Arnica forms rhizomes, which grow in a two-year cycle: the rosette part grows at its front while its tail is slowly dying.[8]

Taxonomy

The Latin specific epithet montana refers to mountains or coming from mountains.[9]

Distribution and habitat

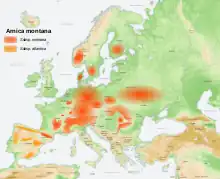

Arnica montana is widespread across most of Europe.[10] It is absent from the British Isles and the Italian and Balkan peninsulas.[11] In addition, it is considered extinct in Hungary and Lithuania.[11] Arnica montana grows in nutrient-poor siliceous meadows or clay soils.[8] It mostly grows on alpine meadows and up to nearly 3,000 m (9,800 ft). In more upland regions, it may also be found on nutrient-poor moors and heaths. However Arnica does not grow on lime soil,[8] thus it is an extremely reliable bioindicator for nutrient poor and acidic soils. It is rare overall, but may be locally abundant. It is becoming rarer, particularly in the north of its distribution, largely due to increasingly intensive agriculture and commercial wild-crafting.[12] Nevertheless, it is cultivated on a large scale in Estonia.[11]

Chemical constituents

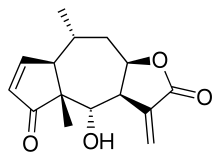

The main constituents of Arnica montana are essential oils, fatty acids, thymol, pseudoguaianolide sesquiterpene lactones and flavanone glycosides.[13] Pseudoguaianolide sesquiterpenes constitute 0.2–0.8% of the flower head of Arnica montana. They are the toxin helenalin and their fatty esters.[14] 2,5-Dimethoxy-p-cymene and thymol methyl ether are the primary components of essential oils from both the plant's roots and rhizomes.[15] The quality and chemical constitution of the plant substance Arnicae flos can be monitored by near-infrared spectroscopy.[13]

Cultivation

Arnica montana is propagated from seed. Generally, 20% of seeds do not germinate. For large scale planting, it is recommended to raise plants first in a nursery and then to transplant them in the field. Seeds sprout in 14–20 days but germination rate depends highly on the seed quality. Planting density for Arnica montana is of 20 plants/m2 such that the maximum yield density will be achieved in the second flowering season. While Arnica montana has high exigencies of soil quality, analyses should be done before any fertilizer input.[16]

The flowers are harvested when fully developed and dried without their bract nor receptacles. The roots can be harvested in autumn and dried as well after being carefully washed.[8]

Arnica montana is sometimes grown in herb gardens.[17]

Use in herbal medicine

Historically, Arnica montana has been used as an herbal medicine for centuries.[17][18][19] Traditional uses for the plant are similar to those for willow bark, with it generally being employed for analgesic and anti-inflammatory purposes.

Clinical trials of Arnica montana have yielded mixed results:

- When used topically in a gel at 50% concentration, A. montana was found to have the same effectiveness (albeit with possibly worse side effects) as a 5% ibuprofen gel for treating the symptoms of hand osteoarthritis.[20]

- A 2014 systematic review found that the available evidence did not support its effectiveness of A. montana at concentrations of 10% or less for pain, swelling, and bruises.[21]

A. montana has also been the subject of studies of homeopathic preparations. A 1998 systematic review of homeopathic A. montana conducted at the University of Exeter found that there are no rigorous clinical trials that support the claim that it is efficacious beyond a placebo effect at the concentrations used in homeopathy.[22]

Toxicity

The US Food and Drug Administration has classified Arnica montana as an unsafe herb because of its toxicity.[4] It should not be taken orally or applied to broken skin where absorption can occur.[4] Arnica irritates mucous membranes and may elicit stomach pain, diarrhea, and vomiting.[4] It may produce contact dermatitis when applied to skin.[4]

Arnica montana contains the toxin helenalin, which can be poisonous if large amounts of the plant are eaten or small amounts of concentrated Arnica are used. Consumption of A. montana can produce severe gastroenteritis, internal bleeding of the digestive tract, raised liver enzymes (which can indicate inflammation of the liver), nervousness, accelerated heart rate, muscular weakness, and death if enough is ingested.[23][24] Contact with the plant can also cause skin irritation.[25][26] In the Ames test, an extract of A. montana was found to be mutagenic.[24]

Market

The demand for A. montana is 50 tonnes per year in Europe, but the supply does not cover the demand. The plant is rare; it is protected in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and in some regions of Switzerland. France and Romania produce A. montana for the international market.[27] Changes in agriculture in Europe during the last decades have led to a decline in the occurrence of A. montana. Extensive agriculture has been replaced by intensive management.[28]

References

- ↑ illustration from Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897

- ↑ The Plant List Arnica montana L.

- ↑ Judith Ladner. "Arnica montana". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Arnica". Drugs.com. May 6, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ↑ Arnica montana L., relevant European medical plant (2014). Waizel-Bucay J., Cruz-Juarez M. de L. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales, Vol. 5 Issue 25 p. 98-109

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "FloraWeb: Daten und Informationen zu Wildpflanzen und zur Vegetation Deutschlands". www.floraweb.de. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Hofmann, Maria (1998). Heilmittel der Natur Arnika. Südwest. ISBN 3-517-08019-5.

- ↑ Archibald William Smith A Gardener's Handbook of Plant Names: Their Meanings and Origins, p. 239, at Google Books

- ↑ "Arnica montana [Arnica]". luirig.altervista.org. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- 1 2 3 http://euromed.luomus.fi/euromed_map.php?taxon=416903&size=medium

- ↑ M. Finlay, Sandra. Advance home remedies. ask1on.

- 1 2 Ivanova, Daniela; Deneva, Vera; Zheleva-Dimitrova, Dimitrina; Balabanova-Bozushka, Vesela; Nedeltcheva, Daniela; Gevrenova, Reneta; Antonov, Liudmil (2019). "Quantitative Characterization of Arnicae flos by RP-HPLC-UV and NIR spectroscopy". Foods. 8 (1): 9. doi:10.3390/foods8010009. PMC 6352279. PMID 30586911.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2007). "Flos Arnicae". Who monographs on selected medicinal plants. Volume 3. Geneve, Switzerland: World Health Organization. pp. 77–87. ISBN 9789241547024.

- ↑ Pljevljakušić, Dejan; Rančić, Dragana; Ristić, Mihailo; Vujisić, Ljubodrag; Radanović, Dragoja; Dajić-Stevanović, Zora (2012). "Rhizome and root yield of the cultivated Arnica montana L., chemical composition and histochemical localization of essential oil". Industrial Crops and Products. 39: 177–189. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.02.030.

- ↑ B.M.Smallfield & M.H. Douglas (2008) Arnica montana a grower‟s guide for commercial production in New Zealand. New Zealand Institute for Crop and Food Research Limited

- 1 2 "Arnica". Flora of North America. efloras.org. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ↑ A. L. Butiuc-Keul; C. Deliu (2001). "Clonal propagation of Arnica montana L., a medicinal plant". In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology – Plant. 37 (5): 581–585. doi:10.1007/s11627-001-0102-2. JSTOR 4293517. S2CID 23435348.

- ↑ Knuesel, O.; Weber, M.; Suter, A. (2002). "Arnica montana gel in osteoarthritis of the knee: An open, multicenter clinical trial". Advances in Therapy. 19 (5): 209–218. doi:10.1007/BF02850361. PMID 12539881. S2CID 21309699.

- ↑ Cameron, M; Chrubasik, S (May 31, 2013). "Topical herbal therapies for treating osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD010538. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010538. PMC 4105203. PMID 23728701.

- ↑ Brito, Noe; Knipschild, Paul; Doreste-Alonso, Jorge (April 11, 2014). "Systematic Review on the Efficacy of Topical Arnica montana for the Treatment of Pain, Swelling and Bruises". Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 22 (2): 216–223. doi:10.3109/10582452.2014.883012. S2CID 76330596.

- ↑ Ernst, E.; Pittler, M. H. (1998). "Efficacy of Homeopathic Arnica". Archives of Surgery. 133 (11): 1187–90. doi:10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1187. PMID 9820349.

- ↑ Gregory L. Tilford (1997). Edible and Medicinal Plants of the West. Mountain Press. ISBN 0-87842-359-1.

- 1 2 "Final report on the safety assessment of Arnica montana extract and Arnica montana". International Journal of Toxicology. 20 Suppl 2 (2): 1–11. 2001. doi:10.1080/10915810160233712. PMID 11558636.

- ↑ "Poisonous Plants: Arnica montana". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ↑ Rudzki E; Grzywa Z (October 1977). "Dermatitis from Arnica montana". Contact Dermatitis. 3 (5): 281–2. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1977.tb03682.x. PMID 145351. S2CID 46223008.

- ↑ Pasquier, B., Godin, M. (2014) L’arnica des montagnes, entre culture et cueillette. Dossier simple et aromatique, Jardins de France 630.

- ↑ Michler, B. (2007) Conservation of Eastern European Medicinal Plants Arnica Montana in Romania

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arnica montana. |

- Royal Society of Medicine Article concerning testing involving Arnica (RSM)

- Botanical.com, a modern herbal Arnica