Neuro-Behçet's disease

| Neuro-Behçet's disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

Behçet's disease with neurological involvement, neuro-Behçet's disease (NBD), involves central nervous system damage in 5–50% of cases.[1] The high variation in the range is due to study design, definition of neurological involvement, ethnic or geographic variation, availability of neurological expertise and investigations, and treatment protocols.

Behçet's disease is recognized as a disease that causes inflammatory perivasculitis, inflammation of the tissue around a blood or lymph vessel, in practically any tissue in the body. Usually, prevalent symptoms include canker sores or ulcers in the mouth and on the genitals, and inflammation in parts of the eye.[2] In addition, patients experience severe headache and papulopustular skin lesions as well. The disease was first described in 1937 by a Turkish dermatologist, Dr. Hulusi Behçet. Behçet's disease is most prevalent in the Middle East and the Far East regions; however, it is rare in America regions.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The initial signs and symptoms of NBD are usually very general. This makes NBD hard to diagnose until the patients experience a severe neurological damage. In addition, the combination of symptoms varies among patients.

Parenchymal neuro-Behçet's disease

The main symptom is meningoencephalitis which happens in ~75% of NBD patients. Other general symptoms of Behçet's disease are also present among parenchymal NBD patients such as fever, headache, genital ulcers, genital scars, and skin lesions. When the brainstem is affected, ophthalmoparesis, cranial neuropathy, and cerebellar or pyramidal dysfunction may be observed. Cerebral hemispheric involvement may result in encephalopathy, hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, seizures, dysphasia, and mental changes including cognitive dysfunction and psychosis. As for the spinal cord involvement, pyramidal signs in the limbs, sensory level dysfunction, and, commonly, sphincter dysfunction may be observed.

Some of the symptoms are less common such as stroke (1.5%), epilepsy (2.2–5%), brain tumor, movement disorder, acute meningeal syndrome, and optic neuropathy.

Non-parenchymal neuro-Behçet's disease

Because Non-parenchymal NBD targets vascular structures, the symptoms arise in the same area. The main clinical characteristic is the cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). If one experiences CVT, a clot in one of the blood vessels in the brain blocks the blood flow and may result in stroke. This happens in the dural venous sinuses. Stroke-like symptoms such as confusion, weakness, and dizziness may be monitored. Headache tends to worsen over the period of several days.

Some of the less common symptoms include intracranial hypertension and intracranial aneurysms.

Related disorder

A related disorder to Neuro-Behçet's disease is neuro-Sweet disease.[4] Sweet disease (or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is a systemic inflammatory disorder characterized by fever, peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis, and neutrophilic infiltrates in the skin, among other symptoms.[5] When complicated by encephalitis or meningitis, it is referred to as neuro-Sweet disease. It is known that treatment with corticosteroids often leads to favorable outcomes. The frequencies of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types B54 and Cw1 are notably high. Several risk factors, including these, are implicated in the development of the condition. Although neuro-Behçet's disease differs in terms of the more common HLA types, it is believed to constitute a spectrum of disorders with shared underlying risk factors.[6]

Causes

Because the cause of Behçet's disease is unknown, the cause responsible for neuro-Behçet's disease is unknown as well. Inflammation starts mainly due to immune system failure. However, no one knows what factors trigger the initiation of auto-immune disease like inflammation. Because the cause is unknown, it is impossible to eliminate or prevent the source that causes the disease. Therefore, treatments are focused on how to suppress the symptoms that hinder daily life activities.[7]

Diagnosis

Although there is a diagnostic criterion for Behçet's disease, one for neuro-Behçet's disease does not exist. Three diagnostic tools are mainly used.

Blood test

60–70% of Japanese and Turkish patients were tested to possess HLA-B51, HLA-B serotype. These patients showed 6 times risk of getting BD. However, the same criteria are not ideal to be applied for Europeans because only 10–20% of European patients showed to possess HLA-B51.

Cerebrospinal fluid level

Cerebrospinal fluid is a clear bodily fluid that occupies the subarachnoid space and the ventricular system around and inside the brain. It is revealed that 70–80% of Parenchymal NBD patients show altered CSF constituents. The observed different is 1) Elevated CSF protein concentration (1 g/dL), 2) Absence of oligoclonal band, and 3) elevated CSF cell count (0–400×106 cells/L) in the body.

Others

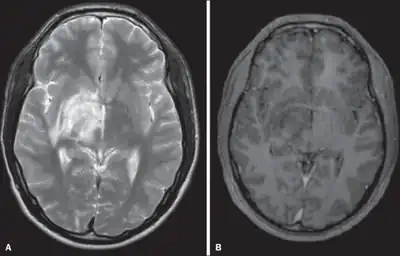

"...Despite its rarity, the patient's ethnic background and the typical radiographic findings should prompt the clinicians to include NBD in the differential diagnosis of optic neuritis and demyelinating disease in the young..."[5]. This quote indicates that even common symptoms such as headache should be recognized as the sign for possible NBD considering the patient's ethnic background.

Types

There are two types of neuro-Behçet's disease: parenchymal and non-parenchymal. The two types of neuro-Behçet's disease rarely occur in the same person. It is suggested that the pathogenesis of the two types are probably different.[3] Statistics indicate that approximately 75% (772 of 1031) BD patients advanced to parenchymal NBD while 17.7% (183 of 1031) of BD patients advanced to non-parenchymal NBD. The remaining 7.3% were not able to be categorized.

Parenchymal

If one experiences parenchymal neuro-Behçet's disease, meningoencephalitis, inflammation of brain, primarily occurs. The target areas of parenchymal NBD include brainstem, spinal cord, and cerebral regions. Sometimes it is hard to determine the affected area because patients are asymptomatic.[8]

Non-parenchymal

In non-parenchymal NBD, vascular complications such as cerebral venous thrombosis primarily occurs. Other distinct characteristics include intracranial aneurysm and extracranial aneurysm. In most cases, veins are much more likely to be affected than arteries. Venous sinus thrombosis is the most frequent vascular manifestation in NBD followed by cortical cerebral veins thrombosis. On the other hand, thrombosis and aneurysms of the large cerebral arteries are rarely reported.[9]

Others

Peripheral nervous system involvement is rarely reported (~0.8%). In this case, Guillain–Barré syndrome, sensorimotor neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, autonomic neuropathy, and subclinical nerve-conduction abnormalities are observed.

Some of the syndromes are not common but recognized for the relation to NBD such as acute meningeal syndrome, tumor-like neuro-Behçet's disease, psychiatric symptoms and optic neuropathy.

Treatment

No definite standard treatment have been set. This is because treatments of the disease has been poorly studied as of 2014.[10] Often in cases of inflammatory parenchymal disease, "corticosteroids should be given as infusions of intravenous methylprednisolone followed by a slowly tapering course of oral steroids". It is suggested that therapy should be continued for a period of time even when the symptoms get suppressed because early relapse may occur. Sometimes, the medical doctors may suggest a different steroid depending on the nature of the disease, the severity, and the response to steroids. According to several studies, parenchymal NBD patients successfully suppress the symptoms with the prescribed steroids. As for non-parenchymal patients, there is no general consensus on how to treat the disease. The reason is that the mechanisms of cerebral venous thrombosis in BD are still poorly understood. Some doctors use anti-coagulants to prevent a clot. On the other hand, some doctors only give steroids and immunosuppressants alone.[11][12]

Epidemiology

In one study of 387 Behçet's disease (BD) patients that has been done for 20 years, 13% of men with BD developed to NBD and 5.6% of women developed to NBD. Combining all statistical reports, approximately 9.4% (43 of 459) BD patients advanced to NBD. In addition, men were 2.8 times more likely to experience NBD than women. This fact indicates possible gender-based pathology.[13][14][15] In speaking about age of NBD patients, the general range was between 20 and 40. NBD patients with age less than 10 or more than 50 were very uncommon.

References

- ↑ Farah S, Al-Shubaili A, Montaser A (1998). "Behçet's syndrome: a report of 41 patients with emphasis on neurological manifestations". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 64 (3): 382–84. doi:10.1136/jnnp.64.3.382. PMC 2169980. PMID 9527155.

- ↑ Serdaroflu P, Yazici H, Ozdemir C, Yurdakul S, Bahar S, Aktin E (1989). "Neurologic involvement in Behçet's syndrome. A prospective study". Arch Neurol. 46 (3): 265–269. doi:10.1001/archneur.1989.00520390031011. PMID 2919979.

- ↑ Yazici H, Fresko I, Yurdakul S (2007). "Behçet's syndrome: disease manifestations, management, and advances in treatment". Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 3 (3): 148–55. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0436. PMID 17334337. S2CID 21869670.

- ↑ Hisanaga, K.; Iwasaki, Y.; Itoyama, Y.; Neuro-Sweet Disease Study Group (2005). "Neuro-Sweet disease: Clinical manifestations and criteria for diagnosis". Neurology. 64 (10): 1756–1761. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000161848.34159.B5. PMID 15911805. S2CID 20773636.

- ↑ Sweet, R. B. (1964). "An Acute Febrile Neutrophtlic Dermatosts". British Journal of Dermatology. 76 (8–9): 349–356. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb14541.x. PMID 14201182. S2CID 53772268.

- ↑ Hisanaga, Kinya (2022). "Neuro-Behçet Disease, Neuro-Sweet Disease, and Spectrum Disorders". Internal Medicine. 61 (4): 447–450. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.8227-21. PMC 8907766. PMID 34615825.

- ↑ Akman-Demir G; Serdaroglu P; Tasçi B; Study Group Neuro-Behçet (1999). "Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet's disease: evaluation of 200 patients". Brain. 122 (11): 2171–2182. doi:10.1093/brain/122.11.2171. PMID 10545401.

- ↑ Kidd D, Steuer A, Denman AM, Rudge P (1999). "Neurological complications of Behçet's syndrome". Brain. 122 (11): 2183–94. doi:10.1093/brain/122.11.2183. PMID 10545402.

- ↑ Tunc R, Saip S, Siva A, Yazici H. Cerebral venous thrombosis is associated with major vessel disease in Behçet's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 1693–94.

- ↑ Nava, F; Ghilotti, F; Maggi, L; Hatemi, G; Del Bianco, A; Merlo, C; Filippini, G; Tramacere, I (18 December 2014). "Biologics, colchicine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants and interferon-alpha for Neuro-Behçet's Syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD010729. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010729.pub2. PMID 25521793.

- ↑ Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasçi B (1999). "Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet's disease: evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behçet Study Group". Brain. 122: 2171–82. doi:10.1093/brain/122.11.2171. PMID 10545401.

- ↑ Al-Fahad S, Al-Araji A (1999). "Neuro-Behçet's disease in Iraq: a study of 40 patients". J Neurol Sci. 170 (2): 105–11. doi:10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00165-3. PMID 10561525. S2CID 24943648.

- ↑ Sorgun, Mine Hayriye; Kural, Mustafa Aykut; Yucesan, Canan (2018). "Clinical characteristics and prognosis of Neuro-Behçet's disease". European Journal of Rheumatology. 5 (4): 235–239. doi:10.5152/eurjrheum.2018.18033. PMC 6267754. PMID 30308139.

- ↑ Ashjazadeh N, Borhani Haghighi A, Samangooie S, Moosavi H (2003). "Neuro-Behçet's disease: a masquerader of multiple sclerosis. A prospective study of neurologic manifestations of Behçet's disease in 96 Iranian patients". Exp Mol Pathol. 74 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1016/S0014-4800(03)80004-7. PMID 12645628.

- ↑ Al-Araji A, Sharquie K, Al-Rawi Z (2003). "Prevalence and patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet's disease: a prospective study from Iraq". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 74 (5): 608–13. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.5.608. PMC 1738436. PMID 12700303.

Further reading

- Al-Araji, A; Kidd, DP (February 2009). "Neuro-Behçet's disease: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management". Lancet Neurology. 8 (2): 192–204. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70015-8. PMID 19161910. S2CID 16483117.

- Koçer, N; Islak, C; Siva, A; Saip, S; Akman, C; Kantarci, O; Hamuryudan, V (Jun–Jul 1999). "CNS involvement in neuro-Behçet syndrome: an MR study". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 20 (6): 1015–24. PMC 7056254. PMID 10445437. Archived from the original on 2023-09-30. Retrieved 2023-09-22.

- Borhani Haghighi, A (April 2009). "Treatment of neuro-Behçet's disease: an update". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 9 (4): 565–74. doi:10.1586/ern.09.11. PMID 19344307. S2CID 136810719.