Pterygium

| Look up pterygium in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Pterygium (plural pterygia or pterygiums) refers to any wing-like triangular membrane occurring in the neck, eyes, knees, elbows, ankles or digits.[1]

The term comes from the Greek word pterygion meaning "wing".

Types

- Popliteal pterygium syndrome, a congenital condition affecting the face, limbs, or genitalia but named after the wing-like structural anomaly behind the knee

- Pterygium (eye) or surfer's eye, a growth on the cornea of the eye

- Pterygium colli or webbed neck, a congenital skin fold of the neck down to the shoulders

- Pterygium inversum unguis or ventral pterygium, adherence of the distal portion of the nailbed to the ventral surface of the nail plate

- Pterygium unguis or dorsal pterygium, scarring between the proximal nail fold and matrix

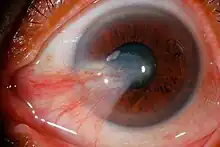

Pterygium of the eye

A pterygium reduces the vision in several ways:

- Distortion of the corneal optics. This begins usually when the pterygium is greater than 2mm from the corneal edge (limbus).

- Disruption of the tear film. The tear film is the first lens in the eye. Pterygia are associated with eyelid inflammation, called Blepharitis.

- Growth over the corneal centre, which leads to dramatic reduction of vision.

- Induced anterior corneal scarring, which often remains after surgical removal.

A pterygium of the eye grows very slowly. Usually it takes several years or decades to progress.

Surgical removal

Indications for surgery, in order of decreasing importance:

- Growth over the corneal centre.

- Reduced vision due to corneal distortion.

- Documented growth.

- Symptoms of discomfort.

- Cosmesis.

Surgery is usually performed under local anaesthetic with light sedation as day surgery. The pterygium is stripped carefully off the surface of the eye. If this is all that is done, the pterygium regrows frequently. The technique with the lowest recurrence rate uses an auto graft of conjunctiva from under the eyelid. This is placed over the defect remaining from the removed pterygium. The graft can be stitched in place, which is time consuming, and painful for the patient afterwards.

An alternative is the use of tissue adhesive fibrin glue (Tisseel or Full Link or Beriplast P or Quixil). A Cochrane Review including 14 studies and last updated October 2016, found that using fibrin glue when doing conjunctival autografting was associated with a reduced likelihood of the pterygium recurring compared with sutures.[2] The review found that operations may take less time but fibrin glue may be associated with more complications (for example, rupture, shrinking and inflammation (granuloma). A 3-year clinical study on the application of ologen collagen matrix as excision site grafts showed significantly improved surgery success rates.[3]

The mechanism of the collagen matrix graft (commercially available as ologen®) works by promoting healthy cell growth into the matrix, thus preventing conjunctiva overgrowth that can cover the iris.[4][5][6]

References

- ↑ Parikh SN, Crawford AH, Do TT, Roy DR (May 2004). "Popliteal pterygium syndrome: implications for orthopaedic management". Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. Part B. 13 (3): 197–201. doi:10.1097/01202412-200405000-00010. PMID 15083121.

- ↑ Romano V, Cruciani M, Conti L, Fontana L (December 2016). Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (ed.). "Fibrin glue versus sutures for conjunctival autografting in primary pterygium surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD011308. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011308.pub2. PMC 6463968. PMID 27911983.

- ↑ Yuan F (2–5 April 2014). PO286 The Efficacy and Safety of the Oculusgen (ologen) Collagen Matrix Implanted During Surgical Excision of Primary Pterygium. The 2014 WOC. Tokyo.

- ↑ Cho CH, Lee SB (October 2015). "Biodegradable collagen matrix (Ologen™) implant and conjunctival autograft for scleral necrosis after pterygium excision: two case reports". BMC Ophthalmology. 15: 140. doi:10.1186/s12886-015-0130-z. PMC 4619331. PMID 26499993.

- ↑ Cho EY, Lee SB (1–3 November 2013). P277: Novel Surgical Therapy Using Biodegradable Collagen Matrix for Ocular Surface Reconstruction of Scleral Thinning after Pterygium Excision. The 2013 KOS. Korea.

- ↑ Waikar S, Srisvstava VK (17–20 January 2013). EP-0351: Management of recurrent symblepharon with pterygium using collagen matrix scaffold implant with autologous limbal stem cell graft. The 2013 APAO-AIOS Congress. Hyderabad, India.

Further reading

- Campbell TG (March 2014). "A radical treatment for surfer's eye". BMJ Case Reports. 2014: bcr2014203896. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-203896. PMC 3975546. PMID 24671326. Lay summary – Live Science (April 8, 2014).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help)