Seabather's eruption

| Seabather's eruption | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pica pica,[1] sea lice, sea poisoning, ocean itch[2] | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Seabather's eruption | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Tingling sensation, itchy rash[1] |

| Complications | Secondary bacterial skin infection[3] |

| Usual onset | Hours to days after exposure[3] |

| Duration | Up to 2 months[1] |

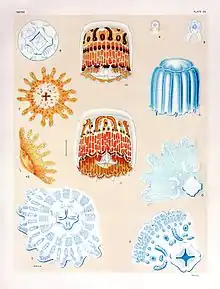

| Causes | Sea anemones and thimble jellyfish[1] |

| Risk factors | Swimming in the ocean[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Seaweed dermatitis, swimmer's itch[1] |

| Prevention | Rinsing off with uncontaminated seawater[1] |

| Treatment | Hydrocortisone, calamine, NSAIDs, antihistamines[1][3] |

| Frequency | Tropics and subtropics[3] |

Seabather's eruption is a rash that occurs due stings by certain sea anemones and thimble jellyfish.[1] Initially there is typically a tingling sensation, followed by the area becoming itchy.[1] The rash generally occurs under a persons swimming suit.[1] Symptoms may last for a few weeks.[1] Complications may include secondary bacterial skin infection.[3]

Most cases occur after swimming in a ocean.[1][3] The underlying mechanism is believed to involve an initial toxin followed by a allergic reaction.[1] It is not spread between people.[3] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms.[1] Other conditions that may appear similar include swimmer's itch.[1]

Treatment may involve the use of hydrocortisone or calamine lotion.[1] NSAIDs and antihistamines may also help.[1][3] Prevention is by rinsing off with uncontaminated seawater after leaving the water.[1] Repeated exposures may result in worse symptoms.[1]

Most cases occur in the tropics and subtropics; though cases have been reported as far North as New York.[3][2] Children may be more severely affected.[3] The condition was initially described in 1949.[1] While the term "sea lice" has been used, it is not caused by the sea louse, a parasite that affects only fish.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms generally arise later after one takes a shower. It is unusual to notice the eruptions immediately. Symptoms can last from a few days up to two weeks, the shorter time being the norm.

The reaction is identified by severe itching around small red papules 1mm to 1.5 cm in size located on areas of skin that were covered by water-permeable clothing or hair during ocean swimming. Initial swimmer exposure to the free-floating larvae produces no effects, as each organism possesses only a single undeveloped nematocyst which is inactive while suspended in seawater. However, due to their microscopic size and sticky bodies, large concentrations of larvae can become trapped in minute gaps between skin and clothing or hair. Once the swimmer leaves the ocean, the organisms stuck against the skin die and automatically discharge their nematocysts when crushed, dried out, or exposed to freshwater. This is why symptoms usually do not appear until the swimmer dries themselves in the sun or takes a freshwater shower without first removing the affected clothing.

Cause

Most cases occur after swimming in a ocean.[1][3] The underlying mechanism is believed to involve an initial toxin followed by a allergic reaction.[1] It is not spread between people.[3] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms.[1] Other conditions that may appear similar include swimmer's itch.[1]

Treatment

Treatment is symptomatic,[5] with most affected using a topical anti-itch cream (diphenhydramine) and a cortisone solution (hydrocortisone).

Frequency

Seabather's eruption is common in the Caribbean, Florida, Mexico, and Gulf States.[6] Cases were first identified in Brazil in 2001.[6]

Swimmers in Queensland, Australia, have reported seabather's eruption during the summer months of the year.[7] Swimmers at the east-coast beaches of Auckland and the rest of the Hauraki Gulf in New Zealand can suffer seabather's eruption, typically during summer.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "Sea bather's eruption | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- 1 2 Auerbach, Paul S.; Cushing, Tracy A.; Harris, N. Stuart (21 September 2016). Auerbach's Wilderness Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1695. ISBN 978-0-323-39609-7. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Quail, MT (January 2019). "Warm water hazard: Sea lice and seabather's eruption". Nursing. 49 (1): 40–43. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000549726.99691.05. PMID 30586048.

- ↑ Tomchik RS, Russell MT, Szmant AM, Black NA (April 1993). "Clinical perspectives on seabather's eruption, also known as 'sea lice'". JAMA. 269 (13): 1669–72. doi:10.1001/jama.269.13.1669. PMID 8455301.

- ↑ Ubillos SS, Vuong D, Sinnott JT, Sakalosky PE (November 1995). "Seabather's eruption". South. Med. J. 88 (11): 1163–5. doi:10.1097/00007611-199511000-00019. PMID 7481994.

- 1 2 Haddad V, Cardoso JL, Silveira FL (2001). "Seabather's eruption: report of five cases in southeast region of Brazil". Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 43 (3): 171–2. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652001000300011. PMID 11452328.

- ↑ "Sea lice: What are the tiny ocean irritants?". www.abc.net.au. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2017-04-24. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ↑ "Fact sheet: Jellyfish stings" (PDF). Auckland Regional Public Health Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

External links

| External resources |

|---|