Shift work

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

Shift work is an employment practice designed to make use of, or provide service across, all 24 hours of the clock each day of the week (often abbreviated as 24/7). The practice typically sees the day divided into shifts, set periods of time during which different groups of workers perform their duties. The term "shift work" includes both long-term night shifts and work schedules in which employees change or rotate shifts.[1][2][3]

In medicine and epidemiology, shift work is considered a risk factor for some health problems in some individuals, as disruption to circadian rhythms may increase the probability of developing cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, diabetes, altered body composition[4] and obesity, among other conditions.[5][6]

Health effects

Shift work increases the risk for the development of many disorders. Shift work sleep disorder is a circadian rhythm sleep disorder characterized by insomnia, excessive sleepiness, or both. Shift work is considered essential for the diagnosis.[7] The risk of diabetes mellitus type 2 is increased in shift workers, especially men. People working rotating shifts are more vulnerable than others.[8]

Women whose work involves night shifts have a 48% increased risk of developing breast cancer.[9][10] This may be due to alterations in circadian rhythm: melatonin, a known tumor suppressor, is generally produced at night and late shifts may disrupt its production.[10] The WHO's International Agency for Research on Cancer listed "shift work that involves circadian disruption" as probably carcinogenic.[11][12] Shift work may also increase the risk of other types of cancer.[13] Working rotating shift work regularly during a two-year interval has been associated with a 9% increased the risk of early menopause compared to women who work no rotating shift work. The increased risk among rotating night shift workers was 25% among women predisposed to earlier menopause. Early menopause can lead to a host of other problems later in life.[14][15] A recent study, found that women who worked rotating night shifts for more than six years, eleven percent experienced a shortened lifespan. Women who worked rotating night shifts for more than 15 years also experienced a 25 percent higher risk of death due to lung cancer.[16]

Shift work also increases the risk of developing cluster headaches,[17] heart attacks,[18] fatigue, stress, sexual dysfunction,[19] depression,[20] dementia, obesity,[7] metabolic disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, and reproductive disorders.[9]

Shift work also can worsen chronic diseases, including sleep disorders, digestive diseases, heart disease, hypertension, epilepsy, mental disorders, substance abuse, asthma, and any health conditions that are treated with medications affected by the circadian cycle.[9] Artificial lighting may additionally contribute to disturbed homeostasis.[21] Shift work may also increase a person's risk of smoking.[9]

The health consequences of shift work may depend on chronotype, that is, being a day person or a night person, and what shift a worker is assigned to. When individual chronotype is opposite of shift timing (day person working night shift), there is a greater risk of circadian rhythms disruption.[22] Nighttime workers sleep an average of 1–4 hours less than daytime workers.[23]

Different shift schedules will have different impacts on the health of a shift worker. The way the shift pattern is designed affects how shift workers sleep, eat and take holidays. Some shift patterns can exacerbate fatigue by limiting rest, increasing stress, overworking staff or disrupting their time off.[24]

Muscle health is also compromised by shift work: altered sleep and eating times, changes to appetite-regulating hormones and total energy expenditure, increased snacking and binge drinking, and reduced protein intake can contribute to negative protein balance, increases in insulin resistance and increases in body fat,[25] resulting in weight gain and more long-term health challenges.[26]

Compared with the day shift, injuries and accidents have been estimated to increase by 15% on evening shifts and 28% on night shifts. Longer shifts are also associated with more injuries and accidents: 10-hour shifts had 13% more and 12-hour shifts had 28% more than 8-hour shifts.[9] Other studies have shown a link between fatigue and workplace injuries and accidents. Workers with sleep deprivation are far more likely to be injured or involved in an accident.[7] Breaks reduce accident risks.[27]

One study suggests that, for those working a night shift (such as 23:00 to 07:00), it may be advantageous to sleep in the evening (14:00 to 22:00) rather than the morning (08:00 to 16:00). The study's evening sleep subjects had 37% fewer episodes of attentional impairment than the morning sleepers.[28]

There are four major determinants of cognitive performance and alertness in healthy shift-workers: circadian phase, sleep inertia, acute sleep deprivation and chronic sleep deficit.[29]

- The circadian phase is relatively fixed in humans; attempting to shift it so that an individual is alert during the circadian bathyphase is difficult. Sleep during the day is shorter and less consolidated than night-time sleep.[7] Before a night shift, workers generally sleep less than before a day shift.[20]

- The effects of sleep inertia wear off after 2–4 hours of wakefulness,[29] such that most workers who wake up in the morning and go to work suffer some degree of sleep inertia at the beginning of their shift. The relative effects of sleep inertia vs. the other factors are hard to quantify; however, the benefits of napping appear to outweigh the cost associated with sleep inertia.

- Acute sleep deprivation occurs during long shifts with no breaks, as well as during night shifts when the worker sleeps in the morning and is awake during the afternoon, prior to the work shift. A night shift worker with poor daytime sleep may be awake for more than 18 hours by the end of his shift. The effects of acute sleep deprivation can be compared to impairment due to alcohol intoxication,[7] with 19 hours of wakefulness corresponding to a BAC of 0.05%, and 24 hours of wakefulness corresponding to a BAC of 0.10%.[9][30] Much of the effect of acute sleep deprivation can be countered by napping, with longer naps giving more benefit than shorter naps.[31] Some industries, specifically the fire service, have traditionally allowed workers to sleep while on duty, between calls for service. In one study of EMS providers, 24-hour shifts were not associated with a higher frequency of negative safety outcomes when compared to shorter shifts.[32]

- Chronic sleep deficit occurs when a worker sleeps for fewer hours than is necessary over multiple days or weeks. The loss of two hours of nightly sleep for a week causes an impairment similar to those seen after 24 hours of wakefulness. After two weeks of such deficit, the lapses in performance are similar to those seen after 48 hours of continual wakefulness.[33] The number of shifts worked in a month by EMS providers was positively correlated with the frequency of reported errors and adverse events.[32]

Sleep assessment during shift work

A cross-sectional study investigated the relationship between several sleep assessment criteria and different shift work schedules (3-day, 6-day, 9-day and 21-day shift) and a control group of day shift work in Korean firefighters.[34] The results found that all shift work groups exhibited significant decreased total sleep time (TST) and decreased sleep efficiency in the night shift but efficiency increased in the rest day.[34] Between-group analysis of the different shift work groups revealed that day shift sleep efficiency was significantly higher in the 6-day shift while night shift sleep efficiency was significantly lower in the 21-day shift in comparison to other shift groups (p < 0.05).[34] Overall, night shift sleep quality was worse in shift workers than those who just worked the day shift, whereas 6-day shift provided better sleep quality compared to the 21-day shift.[34]

Safety and regulation

Shift work has been shown to negatively affect workers, and has been classified as a specific disorder (shift work sleep disorder). Circadian disruption by working at night causes symptoms like excessive sleepiness at work and sleep disturbances. Shift work sleep disorder also creates a greater risk for human error at work.[35] Shift work disrupts cognitive ability and flexibility and impairs attention, motivation, decision making, speech, vigilance, and overall performance.[7]

In order to mitigate the negative effects of shift work on safety and health, many countries have enacted regulations on shift work. The European Union, in its directive 2003/88/EC, has established a 48-hour limit on working time (including overtime) per week; a minimum rest period of 11 consecutive hours per 24-hour period; and a minimum uninterrupted rest period of 24 hours of mandated rest per week (which is in addition to the 11 hours of daily rest).[35][36] The EU directive also limits night work involving "special hazards or heavy physical or mental strain" to an average of eight hours in any 24-hour period.[35][36] The EU directive allows for limited derogations from the regulation, and special provisions allow longer working hours for transportation and offshore workers, fishing vessel workers, and doctors in training (see also medical resident work hours).[36]

Aircraft Traffic Flight Controllers and Pilots

For fewer operational errors, the FAA goal calls for Flight Controllers to be on duty for 5 to 6 hours per shift, with the remaining shift time devoted to meals and breaks.[37] For aircraft pilots, the actual time at the controls (flight time) is limited to 8 or 9 hours, depending on the time of day.[38][39]

Industrial Disasters

Fatigue due to shift work has contributed to several industrial disasters, including the Three Mile Island accident, the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster and the Chernobyl disaster.[7] The Alaska Oil Spill Commission's final report on the Exxon Valdez oil spill disaster found that it was "conceivable" that excessive work hours contributed to crew fatigue, which in turn contributed to the vessel's running aground.[40]

Prevention

Management practices

The practices and policies put in place by managers of round-the-clock or 24/7 operations can significantly influence shift worker alertness (and hence safety) and performance.[41]

Air traffic controllers typically work an 8-hour day, 5 days per week. Research has shown that when controllers remain "in position" for more than two hours, even at low traffic levels, performance can deteriorate rapidly, so they are typically placed "in position" for 30-minute intervals (with 30 minutes between intervals).

These practices and policies can include selecting an appropriate shift schedule or rota and using an employee scheduling software to maintain it, setting the length of shifts, managing overtime, increasing lighting levels, providing shift worker lifestyle training, retirement compensation based on salary in the last few years of employment (which can encourage excessive overtime among older workers who may be less able to obtain adequate sleep), or screening and hiring of new shift workers that assesses adaptability to a shift work schedule.[42] Mandating a minimum of 10 hours between shifts is an effective strategy to encourage adequate sleep for workers. Allowing frequent breaks and scheduling 8- or 10-hour shifts instead of 12-hour shifts can also minimize fatigue and help to mitigate the negative health effects of shift work.[9]

Multiple factors need to be considered when developing optimal shift work schedules, including shift timing, length, frequency and length of breaks during shifts, shift succession, worker commute time, as well as the mental and physical stress of the job.[43] Even though studies support 12-hour shifts are associated with increased occupational injuries and accident (higher rates with subsequent, successive shifts),[44] a synthesis of evidence cites the importance of all factors when considering the safety of a shift.[45]

Shift work was once characteristic primarily of the manufacturing industry, where it has a clear effect of increasing the use that can be made of capital equipment and allows for up to three times the production compared to just a day shift. It contrasts with the use of overtime to increase production at the margin. Both approaches incur higher wage costs. Although 2nd-shift worker efficiency levels are typically 3–5% below 1st shift, and 3rd shift 4–6% below 2nd shift, the productivity level, i.e. cost per employee, is often 25% to 40% lower on 2nd and 3rd shifts due to fixed costs which are "paid" by the first shift.[46]

Shift system

The 42-hour work-week allows for the most even distribution of work time. A 3:1 ratio of work days to days off is most effective for eight-hour shifts, and a 2:2 ratio of work days to days off is most effective for twelve-hour shifts.[41][47][48] Eight-hour shifts and twelve-hour shifts are common in manufacturing and health care. Twelve-hour shifts are also used with a very slow rotation in the petroleum industry. Twenty-four-hour shifts are common in health care and emergency services.[20]

Shift schedule and shift plan

The shift plan or rota is the central component of a shift schedule.[41] The schedule includes considerations of shift overlap, shift change times and alignment with the clock, vacation, training, shift differentials, holidays, etc., whereas the shift plan determines the sequence of work and free days within a shift system.

Rotation of shifts can be fast, in which a worker changes shifts more than once a week, or slow, in which a worker changes shifts less than once a week. Rotation can also be forward, when a subsequent shift starts later, or backward, when a subsequent shift starts earlier.[20] Evidence supports forward rotating shifts are more adaptable for shift workers' circadian physiology.[43]

One main concern of shift workers is knowing their schedule more than two weeks at a time. Shift work is stressful. When on a rotating or ever changing shift, workers have to worry about daycare, personal appointments, and running their households. Many already work more than an eight-hour shift. Some evidence suggests giving employees schedules more than a month in advance would give proper notice and allow planning, their stress level would be reduced.[49]

Management

Though shift work itself remains necessary in many occupations, employers can alleviate some of the negative health consequences of shift work. The United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends employers avoid quick shift changes and any rotating shift schedules should rotate forward. Employers should also attempt to minimize the number of consecutive night shifts, long work shifts and overtime work. A poor work environment can exacerbate the strain of shift work. Adequate lighting, clean air, proper heat and air conditioning, and reduced noise can all make shift work more bearable for workers.[50]

Good sleep hygiene is recommended.[9] This includes blocking out noise and light during sleep, maintaining a regular, predictable sleep routine, avoiding heavy foods and alcohol before sleep, and sleeping in a comfortable, cool environment. Alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption and heavy meals in the few hours before sleep can worsen shift work sleep disorders.[9][7] Exercise in the three hours before sleep can make it difficult to fall asleep.[9]

Free online training programs are available to educate workers and managers about the risks associated with shift work and strategies they can use to prevent these.[51]

Scheduling

Algorithmic scheduling of shift work can lead to what has been colloquially termed as "clopening"[52] where the shift-worker has to work the closing shift of one day and the opening shift of the next day back-to-back resulting in short rest periods between shifts and fatigue. Co-opting employees to fill the shift roster helps to ensure that the human costs[53] are taken into account in a way which is hard for an algorithm to do as it would involve knowing the constraints and considerations of each individual shift worker and assigning a cost metric to each of those factors.[54] Shift based hiring which is a recruitment concept that hires people for individual shifts, rather than hiring employees before scheduling them into shifts enables shift workers to indicate their preferences and availabilities for unfilled shifts through a shift-bidding mechanism. Through this process, the shift hours are evened out by human-driven market mechanism rather than an algorithmic process. This openness can lead to work hours that are tailored to an individual's lifestyle and schedule while ensuring that shifts are optimally filled, in contrast to the generally poor human outcomes of fatigue, stress, estrangement with friends and family and health problems that have been reported with algorithm-based scheduling of work-shifts.[55][56]

Missing income is also a large part of shift worker. Several companies run twenty-four hour shifts. Most of the work is done during the day. When the work dries up, it usually is the second and third shift workers who pay the price. They are told to punch out early or use paid time off if they have any to make up the difference in their paychecks. That practice costs the average worker $92.00 a month.[57]

Medications

Melatonin may increase sleep length during both daytime and nighttime sleep in people who work night shifts. Zopiclone has also been investigated as a potential treatment, but it is unclear if it is effective in increasing daytime sleep time in shift workers. There are, however, no reports of adverse effects.[35]

Modafinil and R-modafinil are useful to improve alertness and reduce sleepiness in shift workers.[35][58] Modafinil has a low risk of abuse compared to other similar agents.[59] However, 10% more participants reported adverse effects (nausea and headache) while taking modafinil. In post-marketing surveillance, modafinil was associated with Stevens–Johnson syndrome. The European Medicines Agency withdrew the license for modafinil for shift workers for the European market because it judged that the benefits did not outweigh the adverse effects.[35]

Using caffeine and naps before night shifts can decrease sleepiness. Caffeine has also been shown to reduce errors made by shift workers.[35]

Epidemiology

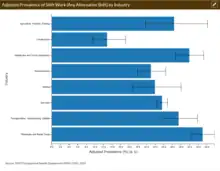

According to data from the National Health Interview Survey and the Occupational Health Supplement, 27% of all U.S. workers in 2015 worked an alternative shift (not a regular day shift) and 7% frequently worked a night shift. Prevalence rates were higher for workers aged 18–29 compared to other ages. Those with an education level beyond high school had a lower prevalence rate of alternative shifts compared to workers with less education. Among all occupations, protective service occupations had the highest prevalence of working an alternative shift (54%).[61]

One of the ways in which working alternative shifts can impair health is through decreasing sleep opportunities. Among all workers, those who usually worked the night shift had a much higher prevalence of short sleep duration (44.0%, representing approximately 2.2 million night shift workers) than those who worked the day shift (28.8%, representing approximately 28.3 million day shift workers). An especially high prevalence of short sleep duration was reported by night shift workers in the transportation and warehousing (69.7%) and health-care and social assistance (52.3%) industries.[62]

Industries

It is estimated that 15-20% of workers in industrialized countries are employed in shift work.[7] Shift work is common in the transportation sector as well. Some of the earliest instances appeared with the railroads, where freight trains have clear tracks to run on at night.

Shift work is also the norm in fields related to public protection and healthcare, such as law enforcement, emergency medical services, firefighting, security and hospitals. Shift work is a contributing factor in many cases of medical errors.[7] Shift work has often been common in the armed forces. Military personnel, pilots, and others that regularly change time zones while performing shift work experience jet lag and consequently suffer sleep disorders.[7]

Those in the field of meteorology, such as the National Weather Service and private forecasting companies, also use shift work, as constant monitoring of the weather is necessary. Much of the Internet services and telecommunication industry relies on shift work to maintain worldwide operations and uptime.

Service industries now increasingly operate on some shift system; for example a restaurant or convenience store will normally be open on most days for much longer than a working day.

There are many industries requiring 24/7 coverage that employ workers on a shift basis, including:

- Caregiver

- Direct support professional

- Customer service including call centers

- Data center and IT Operations

- Death care (medical examiner or coroner)

- Emergency services

- Police

- Firefighting

- Emergency medical services

- Entertainment

- Casino workers

- Health care

- Funeral workers

- Hospitality

- Logistics & transportation

- Railways

- Ship Crew

- Manufacturing

- Military

- Mining

- Public utilities

- Nuclear power

- Fossil fuel

- Solar, wind, and hydro power

- Retail

- Telecommunications

- Television

- Radio broadcasting

- Security

- Weather

See also

- Effects of overtime

- Fatigue Avoidance Scheduling Tool

- Gantt chart

- Occupational Cancer

- Sleep

- Split shift

References

- ↑ Sloan Work & Family Research, Boston College. "Shift work, Definition(s) of". Retrieved 2014-09-25.

- ↑ Institute for Work & Health, Ontario, Canada (2010). "Shift work and health". Retrieved 2018-08-05.

...employment with anything other than a regular daytime work schedule

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment (1991). "Biological Rhythms: Implications for the Worker".

- ↑ Sooriyaarachchi P, Jayawardena R, Pavey T, King N. Shift work and body composition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Endocrinology. 2021 Jun.https://doi.org/10.23736/s2724-6507.21.03534-x

- ↑ Delezie J; Challet E (2011). "Interactions between metabolism and circadian clocks: reciprocal disturbances". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1243 (1): 30–46. Bibcode:2011NYASA1243...30D. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06246.x. PMID 22211891. S2CID 43621902.

- ↑ Scheer FA; Hilton MF; Mantzoros CS; Shea SA (2009). "Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (11): 4453–8. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.4453S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808180106. PMC 2657421. PMID 19255424.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Ker, Katharine; Edwards, Philip James; Felix, Lambert M.; Blackhall, Karen; Roberts, Ian (2010). "Caffeine for the prevention of injuries and errors in shift workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD008508. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008508. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4160007. PMID 20464765.

- ↑ Yong, Gan (2014). "Shift work and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 72 (1): 72–78. doi:10.1136/oemed-2014-102150. PMID 25030030. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Caruso, Claire C. (August 2, 2012). "Running on Empty: Fatigue and Healthcare Professionals". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH.

- 1 2 Megdal, S. P.; Kroenke, C. H.; Laden, F.; Pukkala, E.; Schernhammer, E. S. (2005). "Night work and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis". European Journal of Cancer. 41 (13): 2023–2032. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.010. PMID 16084719.

- ↑ IARC Press release No. 180 Archived 2008-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ WNPR, Connecticut Public Radio. "The health of night shift workers". Connecticut Public Radio, WNPR. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ↑ Parent, M. -E.; El-Zein, M.; Rousseau, M. -C.; Pintos, J.; Siemiatycki, J. (2012). "Night Work and the Risk of Cancer Among Men". American Journal of Epidemiology. 176 (9): 751–759. doi:10.1093/aje/kws318. PMID 23035019.

- ↑ Stock, D.; Knight, J. A.; Raboud, J.; Cotterchio, M.; Strohmaier, S.; Willett, W.; Eliassen, A. H.; Rosner, B.; Hankinson, S. E.; Schernhammer, E. (2019-03-01). "Women who work nights are 9% more likely to have an early menopause". Human Reproduction. 34 (3): 539–548. doi:10.1093/humrep/dey390. PMC 7210710. PMID 30753548.

- ↑ Stock, D.; Hankinson, S. E.; Rosner, B.; Eliassen, A. H.; Willett, W.; Strohmaier, S.; Cotterchio, M.; Raboud, J.; Knight, J. A.; Schernhammer, E. (2019-03-01). "Rotating night shift work and menopausal age". Human Reproduction. 34 (3): 539–548. doi:10.1093/humrep/dey390. ISSN 0268-1161. PMC 7210710. PMID 30753548.

- ↑ "Why Working The Night Shift Has Major Health Consequences". HuffPost. 2015-01-06. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ↑ Beck, E.; Sieber, W. J.; Trejo, R. (2005). "Management of cluster headache". American Family Physician. 71 (4): 717–724. PMID 15742909.

- ↑ Vyas MV; Garg AX; Iansavichus AV; Costella J; Donner A; Laugsand LE; Janszky I; Mrkobrada M; Parraga G; Hackam DG (July 2012). "Shift work and vascular events: systematic review and meta-analysis". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition). 345: e4800. doi:10.1136/bmj.e4800. PMC 3406223. PMID 22835925.

- ↑ Fido A; Ghali A (2008). "Detrimental effects of variable work shifts on quality of sleep, general health and work performance". Med Princ Pract (Abstract). 17 (6): 453–7. doi:10.1159/000151566. PMID 18836273.

- 1 2 3 4 Slanger, Tracy E; Gross, J. Valérie; Pinger, Andreas; Morfeld, Peter; Bellinger, Miriam; Duhme, Anna-Lena; Reichardt Ortega, Rosalinde Amancay; Costa, Giovanni; Driscoll, Tim R; Foster, Russell G; Fritschi, Lin; Sallinen, Mikael; Liira, Juha; Erren, Thomas C (23 August 2016). "Person-directed, non-pharmacological interventions for sleepiness at work and sleep disturbances caused by shift work". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (8): CD010641. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010641.pub2. PMC 8406755. PMID 27549931.

- ↑ Navara, Kristen J.; Nelson, Randy J. (October 2007). "The dark side of light at night: physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences". Journal of Pineal Research. 43 (3): 215–224. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00473.x. PMID 17803517.

- ↑ Adan, Ana; Archer, Simon N.; Hidalgo, Maria Paz; Di Milia, Lee; Natale, Vincenzo; Randler, Christoph (24 September 2012). "Circadian Typology: A Comprehensive Review" (PDF). Chronobiology International. 29 (9): 1153–1175. doi:10.3109/07420528.2012.719971. PMID 23004349. S2CID 7565248.

- ↑ Ftouni, Suzanne; Sletten, Tracey L.; Barger, Laura K.; Lockley, Steven W.; Rajaratnam, Shantha M.W. (2012). "Shift Work Disorder". In Barkoukis, Teri J.; Matheson, Jean K.; Ferber, Richard; Doghramji, Karl (eds.). Therapy in Sleep Medicine. pp. 378–389. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4377-1703-7.10029-5. ISBN 978-1-4377-1703-7.

- ↑ Fatigue and Shift Work (Tools And Techniques) eBook: Dr Angela Moore, Alec Jezewski: Amazon.co.uk: Kindle Store. 9 September 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ {Sooriyaarachchi P, Jayawardena R, Pavey T, King N. Shift work and body composition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Endocrinology. 2021 Jun. https://doi.org/10.23736/s2724-6507.21.03534-x

- ↑ Lamon, Séverine; Zacharewicz, Evelyn; Condo, Dominique; Aisbett, Brad (March 2017). "The Impact of Shiftwork on Skeletal Muscle Health". Nutrients. 9 (3): 248. doi:10.3390/nu9030248. PMC 5372911. PMID 28282858.

- ↑ Fischer, Dorothee; Lombardi, David A.; Folkard, Simon; Willetts, Joanna; Christiani, David C. (2017-11-26). "Updating the "Risk Index": A systematic review and meta-analysis of occupational injuries and work schedule characteristics". Chronobiology International. 34 (10): 1423–1438. doi:10.1080/07420528.2017.1367305. ISSN 0742-0528. PMID 29064297. S2CID 39842142.

- ↑ Santhi, N; Aeschbach D, Horowitz TS, Czeisler CA (2008). "The impact of sleep timing and bright light exposure on attentional impairment during night work" (abstract online). J Biol Rhythms. 23 (4): 341–52. doi:10.1177/0748730408319863. PMC 2574505. PMID 18663241. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Barger, Laura; Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SMW, Landrigan CP (2009). "Neurobehavioral, Health, and Safety Consequences Associated With Shift Work in Safety-Sensitive Professions". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 9 (2): 9:155–164. doi:10.1007/s11910-009-0024-7. PMID 19268039. S2CID 22518201.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dawson, D; Reid, K (1997). "Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment". Nature. 388 (6639): 235. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..235D. doi:10.1038/40775. PMID 9230429. S2CID 4424846.

- ↑ Mollicone, DJ; Van Dongen, HPA; Dinges, DF (2007). "Optimizing sleep/wake schedules in space: Sleep during chronic nocturnal sleep restriction with and without diurnal naps". Acta Astronautica. 60 (4–7): 354–361. Bibcode:2007AcAau..60..354M. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2006.09.022.

- 1 2 Patterson PD; Weaver MD; Frank RC; Warner CW; Martin-Gill C; Guyette FX; Fairbanks RJ; Hubble MW; Songer TJ; Calloway CW; Kelsey SF; Hostler D (2012). "Association Between Poor Sleep, Fatigue, and Safety Outcomes in Emergency Medical Services Providers". Prehospital Emergency Care. 16 (1): 86–97. doi:10.3109/10903127.2011.616261. PMC 3228875. PMID 22023164.

- ↑ Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, DingesDF (2003). "The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation". Sleep (26): 117–126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Jeong, Kyoung Sook; Ahn, Yeon-Soon; Jang, Tae-Won; Lim, Gayoung; Kim, Hyung Doo; Cho, Seung-Woo; Sim, Chang-Sun (2019-09-01). "Sleep Assessment During Shift Work in Korean Firefighters: A Cross-Sectional Study". Safety and Health at Work. 10 (3): 254–259. doi:10.1016/j.shaw.2019.05.003. ISSN 2093-7911. PMC 6717904. PMID 31497322.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Liira, J; Verbeek, JH; Costa, G; Driscoll, TR; Sallinen, M; Isotalo, LK; Ruotsalainen, JH (Aug 12, 2014). "Pharmacological interventions for sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD009776. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009776.pub2. PMID 25113164.

- 1 2 3 Directive 2003/88/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 November 2003 concerning certain aspects of the organisation of working time.

- ↑ Beth Kassab (2006). "Mistakes increase at airport: An incident involving 2 jets at Orlando International focuses attention on air-traffic errors". Knight Ridder Tribune.

- ↑ "Flightcrew Member Duty and Rest Requirements". The Federal Register. 2012.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ↑ G. Brogmus, G.; W. Maynard (2006). "Safer shiftwork through more effective scheduling". Occupational Hazards.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ↑ Final Report: Spill--The Wreck of the Exxon Valdez: Implications for Safe Transportation of Oil, Alaska Oil Spill Commission (February 1990).

- 1 2 3 Miller, JC (2013). "Fundamentals of Shiftwork Scheduling, 3rd Edition: Fixing Stupid". Smashwords.

- ↑ Inc., Intrigma. "Five Foundations For A Fair Physician Schedule". Archived from the original on 2016-08-12. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- 1 2 Knauth, Peter; Hornberger, Sonia (2003-03-01). "Preventive and compensatory measures for shift workers". Occupational Medicine. 53 (2): 109–116. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqg049. ISSN 0962-7480. PMID 12637595.

- ↑ Folkard, Simon; Lombardi, David A. (2006-11-01). "Modeling the impact of the components of long work hours on injuries and "accidents"". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 49 (11): 953–963. doi:10.1002/ajim.20307. ISSN 1097-0274. PMID 16570251.

- ↑ Philip., Tucker (2012). Working time, health and safety : a research synthesis paper. Folkard, Simon., International Labour Office. Geneva: ILO. ISBN 9789221260615. OCLC 795699411.

- ↑ Alan Blinder and William Baumol 1993, Economics: Principles and Policy, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, p. 687.

- ↑ Knauth, P; Rohmert, W; Rutenfranz, J (March 1979). "Systematic selection of shift plans for continuous production with the aid of work-physiological criteria". Applied Ergonomics. 10 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1016/0003-6870(79)90003-6. PMID 15676345.

- ↑ Rutenfranz, J; Knauth, P; Colquhoun, W (May 1976). "Hours of work and shiftwork". Ergonomics. 19 (3): 331–340. doi:10.1080/00140137608931549. PMID 976239.

- ↑ pierce (2016-08-29). "Keeping it Balanced: The Art of Scheduling Rotating Shifts". Mitrefinch. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ↑ Roger R. Rosa; Michael J. Colligan (July 1997). Plain Language About Shiftwork (PDF). Cincinnati, Ohio: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-21.

- ↑ "CDC - Work Schedules: Shift Work and Long Hours - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ↑ "The 'Clopening' Shift May Soon Be a Thing of the Past". Boston.com. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "WSMH" (PDF).

- ↑ http://ewh.ieee.org/conf/hfpp/presentations/27.pdf

- ↑ Greenhouse, Steven (22 February 2015). "In Service Sector, No Rest for the Working". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "Starbucks 'Clopening' Practices Deemed Inexcusable". Forbes. 19 August 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "Nonstandard work schedules over the life course: A first look" (PDF).

- ↑ Morgenthaler, TI; Lee-Chiong, T; Alessi, C; Friedman, L; Aurora, RN; Boehlecke, B; Brown, T; Chesson AL, Jr; Kapur, V; Maganti, R; Owens, J; Pancer, J; Swick, TJ; Zak, R; Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep, Medicine (Nov 2007). "Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report". Sleep. 30 (11): 1445–59. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445. PMC 2082098. PMID 18041479.

- ↑ Wisor, Jonathan (2013). "Modafinil as a Catecholaminergic Agent: Empirical Evidence and Unanswered Questions". Frontiers in Neurology. 4: 139. doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00139. PMC 3791559. PMID 24109471.

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Worker Health Charts". wwwn.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Worker Health Charts".

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 27, 2012). "Short sleep duration among workers—United States, 2010". MMWR. 61 (16): 281–285. PMID 22534760.

Further reading

- Pati, A.K., Chandrawanshi, A. & Reinberg, A. (2001) 'Shift work: consequences and management'. Current Science, 81(1), 32–52.

- Knutsson, Anders; Jonsson, BjornG.; Akerstedt, Torbjorn; Orth-Gomer, Kristina (July 1986). "Increased risk of ischaemic heart disease in shift workers". The Lancet. 328 (8498): 89–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91619-3. PMID 2873389. S2CID 21921096.

- Burr, Douglas Scott (2009) 'The Schedule Book', 'ISBN 978-1-4392-2674-2'.

- Miller, James C. (2013) 'Fundamentals of Shiftwork Scheduling, 3rd Edition: Fixing Stupid', Smashwords.

External links

- Shift work and health, Issue Briefing, Institute for Work & Health, April 2010.

- Scientific Symposium on the Health Effects of Shift Work, Toronto, 12 April 2010, hosted by the Occupational Cancer Research Centre and the Institute for Work & Health (IWH).

- CDC - Work Schedules: Shift Work and Long Work Hours - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- Three-hour night shift system, For a crew of three on a small boat at sea

- Working Time Society, a global research society addressing questions of working time and shift-work with biannual symposia.

- Consensus papers regarding Health, ... and Shiftwork (2019) of the ICOH-Scientific Committee on Shiftwork and Working Time and the Working Time Society