History of tuberculosis

Throughout history, the disease tuberculosis has been variously known as consumption, phthisis, and the White Plague. It is generally accepted that the causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis originated from other, more primitive organisms of the same genus Mycobacterium. In 2014, results of a new DNA study of a tuberculosis genome reconstructed from remains in southern Peru suggest that human tuberculosis is less than 6,000 years old. Even if researchers theorise that humans first acquired it in Africa about 5,000 years ago,[1] there is evidence that the first tuberculosis infection happened about 9,000 years ago.[2] It spread to other humans along trade routes. It also spread to domesticated animals in Africa, such as goats and cows. Seals and sea lions that bred on African beaches are believed to have acquired the disease and carried it across the Atlantic to South America. Hunters would have been the first humans to contract the disease there.[1]

Origins

Scientific work investigating the evolutionary origins of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex has concluded that the most recent common ancestor of the complex was a human-specific pathogen, which underwent a population bottleneck. Analysis of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units has allowed dating of the bottleneck to approximately 40,000 years ago, which corresponds to the period subsequent to the expansion of Homo sapiens sapiens out of Africa. This analysis of mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units also dated the Mycobacterium bovis lineage as dispersing approximately 6,000 years ago, which may be linked to animal domestication and early farming.[3]

Human bones from the Neolithic show presence of the bacteria. There has also been a claim of evidence of lesions characteristic of tuberculosis in a 500,000-year-old Homo erectus fossil, although this finding is controversial.[4]

Results of a genome study reported in 2014 suggest that tuberculosis is newer than previously thought. Scientists were able to recreate the genome of the bacteria from remains of 1,000-year-old skeletons in southern Peru. In dating the DNA, they found it was less than 6,000 years old. They also found it related most closely to a tuberculosis strain in seals, and have theorized that these animals were the mode of transmission from Africa to South America.[1] The team from University of Tübingen believe that humans acquired the disease in Africa about 5,000 years ago.[1] Their domesticated animals, such as goats and cows, contracted it from them. Seals acquired it when coming up on African beaches for breeding, and carried it across the Atlantic. In addition, TB spread via humans on the trade routes of the Old World. Other researchers have argued there is other evidence that suggests the tuberculosis bacteria is older than 6,000 years.[1] This TB strain found in Peru is different from that prevalent today in the Americas, which is more closely related to a later Eurasian strain likely brought by European colonists.[5] However, this result is criticised by other experts from the field,[1] for instance because there is evidence of the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 9000 year old skeletal remains.[2]

Although relatively little is known about its frequency before the 19th century, its incidence is thought to have peaked between the end of the 18th century and the end of the 19th century. Over time, the various cultures of the world gave the illness different names: phthisis (Greek),[6] consumptio (Latin), yaksma (India), and chaky oncay (Incan), each of which make reference to the "drying" or "consuming" effect of the illness, cachexia.

In the 19th century, TB's high mortality rate among young and middle-aged adults and the surge of Romanticism, which stressed feeling over reason, caused many to refer to the disease as the "romantic disease".

Tuberculosis in early civilization

| |

In 2008, evidence for tuberculosis infection was discovered in human remains from the Neolithic era dating from 9,000 years ago, in Atlit Yam, a settlement in the eastern Mediterranean.[7] This finding was confirmed by morphological and molecular methods; to date it is the oldest evidence of tuberculosis infection in humans.

Evidence of the infection in humans was also found in a cemetery near Heidelberg, in the Neolithic bone remains that show evidence of the type of angulation often seen with spinal tuberculosis.[8] Some authors call tuberculosis the first disease known to mankind.

Signs of the disease have also been found in Egyptian mummies dated between 3000 and 2400 BC.[9] The most convincing case was found in the mummy of priest Nesperehen, discovered by Grebart in 1881, which featured evidence of spinal tuberculosis with the characteristic psoas abscesses.[10] Similar features were discovered on other mummies like that of the priest Philoc and throughout the cemeteries of Thebes. It appears likely that Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti both died from tuberculosis, and evidence indicates that hospitals for tuberculosis existed in Egypt as early as 1500 BC.[11]

The Ebers papyrus, an important Egyptian medical treatise from around 1550 BC, describes a pulmonary consumption associated with the cervical lymph nodes. It recommended that it be treated with the surgical lancing of the cyst and the application of a ground mixture of acacia seyal, peas, fruits, animal blood, insect blood, honey and salt.

The Old Testament mentions a consumptive illness that would affect the Jewish people if they stray from God. It is listed in the section of curses given before they enter the land of Canaan.[12]

The East

Ancient India

The first references to tuberculosis in non-European civilization is found in the Vedas. The oldest of them (Rigveda, 1500 BC) calls the disease yaksma.[13] The Atharvaveda calls it balasa. It is in the Atharvaveda that the first description of scrofula is given.[14] The Sushruta Samhita, written around 600 BC, recommends that the disease be treated with breast milk, various meats, alcohol and rest.[15] The Yajurveda advises affected individuals to move to higher altitudes.[15]

Ancient China

The Classical Chinese word lào 癆 "consumption; tuberculosis" was the common name in traditional Chinese medicine and fèijiéhé 肺結核 (lit. "lung knot kernel") "pulmonary tuberculosis" is the modern medical term. Lao is compounded in names like xulao 虛癆 with "empty; void", láobìng 癆病 with "sickness", láozhài 癆瘵 with "[archaic] sickness", and feilao 肺癆 with "lungs". Zhang and Unschuld explain that the medical term xulao 虛癆 "depletion exhaustion" includes infectious and consumptive pathologies, such as laozhai 癆瘵 "exhaustion with consumption" or laozhaichong 癆瘵蟲 "exhaustion consumption bugs/worms".[16] They retrospectively identify feilao 肺癆 "lung exhaustion" and infectious feilao chuanshi 肺癆傳尸 "lung exhaustion by corpse [evil] transmission as "consumption/tuberculosis".[17] Describing foreign loanwords in early medical terminology, Zhang and Unschuld note the phonetic similarity between Chinese feixiao 肺消 (from Old Chinese **pʰot-ssew) "lung consumption" and ancient Greek phthisis "pulmonary tuberculosis".[18]

The Huangdi Neijing classic Chinese medical text (c. 400 BCE – 260 CE), traditionally attributed to the mythical Yellow Emperor, describes a disease believed to be tuberculosis, called xulao bing (虛癆病 "weak consumptive disease"), characterized by persistent cough, abnormal appearance, fever, a weak and fast pulse, chest obstructions, and shortness of breath.[19]

The Huangdi Neijing describes an incurable disease called huaifu 壞府 "bad palace", which commentators interpret as tuberculous. "As for a string which is cut, its sound is hoarse. As for wood which has become old, its leaves are shed. As for a disease which is in the depth [of the body], the sound it [generates] is hiccup. When a man has these three [states], this is called 'destroyed palace'. Toxic drugs do not bring a cure; short needles cannot seize [the disease].[20] Wang Bing's commentary explains that fu 府 "palace" stands for xiong 胸 "chest", and huai "destroy" implies "injure the palace and seize the disease". The Huangdi Neijing compiler Yang Shangshan notes, "The [disease] proposed here very much resembles tuberculosis ... Hence [the text] states: poisonous drugs bring no cure; it cannot be seized with short needles."[21]

The Shennong Bencaojing pharmacopeia (c. 200–250 CE), attributed to the legendary inventor of agriculture Shennong "Divine Farmer", also refers to tuberculosis[22]

The Zhouhou beiji fang 肘后备急方 "Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies", attributed to the Daoist scholar Ge Hong (263–420), uses the name of shizhu 尸疰 "corpse disease; tuberculosis" and describes the symptoms and contagion:

"This disease has many changing symptoms varying from thirty-six to ninety-nine different kinds. Generally it gives rise to a high fever, sweating, asthenia, unlocalised pains, making all positions difficult. Gradually, after months and years of suffering, this lingering disease brings about death to the sufferer. Afterwards it is transferred to others until the whole family is wiped out."[23]

Song dynasty (920–1279) Daoist priest-doctors first recorded that tuberculosis, called shīzhài 尸瘵 (lit. "corpse disease") "disease which changes a living being into a corpse",[24] was caused by a specific parasite or pathogen, centuries earlier than their contemporaries in other countries. The Duanchu shizhai pin 斷除尸瘵品 "On the Extermination of the Corpse Disease" is the 23rd chapter in Daoist collection Wushang xuanyuan santian Yutang dafa 無上玄元三天玉堂大法 "Great Rites of the Jade Hall of the Three Heavens of the Supreme Mysterious Origins" (Daozang number 103). The text has a preface dated 1126, written by the Song dynasty Zhengyi Dao master Lu Shizhong 路時中, who founded the Yutang dafa 玉堂大法 tradition, but internal evidence reveals that the text could not have been written before 1158.[25]

The disaster of the contagious disease, which changes a living being into a corpse, is caused by the infectious [nature] of the nine [kinds of] parasites (ch'ung 蟲). It is also caused by overworking one's mind and exhausting one's energy, injuring one's ch'i and loosening one's sperm—all of which happen to common folk. When the original vitality is being [gradually] exhausted, the evil aura begins to be transmitted through the affected vital ch'i [of the sick body]. ... The aspects of the illness vary, and the causes of contamination are different. Rooms and food are capable of gradual contamination, and the clothes worn by the indisposed are twined easily with the infectious ch'i and these two become inseparable. ... The symptoms of the disease: When it begins, the sufferer coughs and pants; he spits blood [pulmonary hemorrhage]; he is emaciated and skinny; cold and fever affect him intermittently, and his dreams are morbid. This is the evidence that this person is suffering from the disease which is also known as wu-ch'uan 屋傳 [contagious disease contracted from a sick-room]. ... The disease may be contracted by a healthy person who happens to have slept in the same bed with the patient, or worn his clothes. After the death of the sufferer, the clothes, curtains, bed or couch, vessels and utensils used by him are known to have been contaminated by and saturated with the polluted ch'i in which the noxious ku 蠱 [parasites or germs] take their abode. Stingy people wish to keep them for further use, and the poorer families cannot afford to get rid of them and buy everything anew. Isn't this lamentable, since it creates the cause of the great misfortune yet to come![26]

This passage refers to the cause of TB in ancient medical terminology of jiuchong 九蟲 "Nine Worms" and gu 蠱 "supernatural agents causing disease", and qi. The Nine Worms generically meant "bodily parasites; intestinal worms" and were associated with the sanshi 三尸 "Three Corpses" or sanchong 三蟲 "Three Worms", which were believed to be biospiritual parasites that live in the human body and seek to hasten their host's death. Daoist medical texts give different lists and descriptions of the Nine Worms. The Boji fang 博濟方 "Prescriptions for Universal Dispensation", collected by Wang Gun王袞 (fl. 1041), calls the supposed TB pathogen laochong 癆蟲 "tuberculosis worms".[27]

This Duanchu shizhai pin chapter (23/7b-8b) explains that the present Nine Worms does not refer to the intestinal weichong 胃蟲 "stomach worms", huichong 蛔蟲 "coiling worm; roundworm", or cun baichong 寸白蟲 "inch-long white worm; nematode", and says the supposed six TB worms are "six kinds" of parasites, but the next chapter (24/20a-21b) says they are "six stages/generations" of reproduction.[28] Daoist priests allegedly cured tuberculosis through drugs, acupuncture, and burning fulu "supernatural talismans/charms". Burning magic talismans would cause the TB patient to cough, which was considered an effective treatment.

To cure the disease, it is necessary to produce a spout of smoke by burning off thirty-six charms, and instruct the patient to inhale and to swallow up its fumes, whether he likes it or not. By the time all charms are used up, the smoke should also be dispersed. It may be difficult for the patient to bear the odour of the smoke at first, but once he gets used to such a smell, it does not really matter. Whenever the patient feels that there is phlegm in his throat, he is advised to cough and spit it out. If the patient is greatly affected by the symptoms, it will be good if his spittle is thick and if he can spit it out. When the patient is less affected by the wicked ch'i, he does not have much phlegm to eject, but if he is deeply affected, he tends to vomit and to expectorate heavily until everything is cleared up, and then his illness is cured. When the wicked element is rooted out, it does not need to be fumigated any more [with charms].[29]

In addition, Daoist healers would burn talismans in order to fumigate the clothes and belongings of the deceased, and would warn the tuberculosis patient's family to throw away everything into a changliu shui 長流水 "everflowing stream". According to Liu Ts'un-yan,[30] "This proves that the priests of the time actually wanted to destroy all the belongings of the deceased, using charms as a camouflage."

Classical antiquity

Hippocrates, in Book 1 of his Of the Epidemics, describes the characteristics of the disease: fever, colourless urine, cough resulting in a thick sputa, and loss of thirst and appetite. He notes that most of those affected became delirious before they died from the disease.[31] Hippocrates and many other at the time believed phthisis to be hereditary in nature.[32] Aristotle disagreed, believing the disease was contagious.

Pliny the Younger wrote a letter to Priscus in which he details the symptoms of phthisis as he saw them in Fannia:

The attacks of fever stick to her, her cough grows upon her, she is in the highest degree emaciated and enfeebled.

— Pliny the Younger, Letters VII, 19

Galen proposed a series of therapeutic treatments for the disease, including: opium as a sleeping agent and painkiller; blood letting; a diet of barley water, fish, and fruit. He also described the phyma (tumor) of the lungs, which is thought to correspond to the tubercles that form on the lung as a result of the disease.[33]

Vitruvius noted that "cold in the windpipe, cough, plurisy, phthisis, [and] spitting blood", were common diseases in regions where the wind blew from north to northwest, and advised that walls be so built as to shelter individuals from the winds.[34]

Aretaeus was the first person to rigorously describe the symptoms of the disease in his text De causis et signis diuturnorum morborum:[35]

Voice hoarse; neck slightly bent, tender, not flexible, somewhat extended; fingers slender, but joints thick; of the bones alone the figure remains, for the fleshy parts are wasted; the nails of the fingers crooked, their pulps are shrivelled and flat...Nose sharp, slender; cheeks prominent and red; eyes hollow, brilliant and glittering; swollen, pale or livid in countenance; the slender parts of the jaws rest on the teeth as, as if smiling; otherwise of cadaverous aspect...

— De causis et signis diuturnorum morborum, Aretaeus, translated by Francis Adams

In his other book De curatione diuturnorum morborum, he recommends that affected individuals travel to high altitudes, travel by sea, eat a good diet and drink plenty of milk.[36]

Pre-Columbian America

In South America, reports of a study in August 2014 revealed that TB had likely been spread via seals that contracted it on beaches of Africa, from humans via domesticated animals, and carried it across the Atlantic. A team at the University of Tübingen analyzed tuberculosis DNA in 1,000-year-old skeletons of the Chiribaya culture in southern Peru; so much genetic material was recovered that they could reconstruct the genome. They learned that this TB strain was related most closely to a form found only in seals.[1] In South America, it was likely contracted first by hunters who handled contaminated meat. This TB is a different strain from that prevalent today in the Americas, which is more closely related to a later Eurasian strain.[5][37]

Prior to this study, the first evidence of the disease in South America was found in remains of the Arawak culture around 1050 BC.[38] The most significant finding belongs to the mummy of an 8 to 10-year-old Nascan child from Hacienda Agua Sala, dated to 700 AD. Scientists were able to isolate evidence of the bacillus.[38]

Europe: Middle Ages and Renaissance

During the Middle Ages, no significant advances were made regarding tuberculosis. Avicenna and Rhazes continued to consider to believe the disease was both contagious and difficult to treat. Arnaldus de Villa Nova described etiopathogenic theory directly related to that of Hippocrates, in which a cold humor dripped from the head into the lungs.

In Medieval Hungary, the Inquisition recorded the trials of pagans. A document from the 12th century recorded an explanation of the cause of illness. The pagans said that tuberculosis was produced when a dog-shaped demon occupied the person's body and started to eat his lungs. When the possessed person coughed, then the demon was barking, and getting close to his objective, which was to kill the victim.[39]

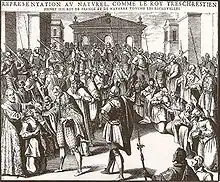

Royal touch

Monarchs were seen as religious figures with magical or curative powers. It was believed that royal touch, the touch of the sovereign of England or France, could cure diseases due to the divine right of sovereigns.[40] King Henry IV of France usually performed the rite once a week, after taking communion.[41] So common was this practice of royal healing in France, that scrofula became known as the "mal du roi" or the "King's Evil".

Initially, the touching ceremony was an informal process. Sickly individuals could petition the court for a royal touch and the touch would be performed at the King's earliest convenience. At times, the King of France would touch affected subjects during his royal walkabout. The rapid spread of tuberculosis across France and England, however, necessitated a more formal and efficient touching process. By the time of Louis XIV of France, placards indicating the days and times the King would be available for royal touches were posted regularly; sums of money were doled out as charitable support.[41][42] In England, the process was extremely formal and efficient. As late as 1633, the Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican Church contained a Royal Touch ceremony.[43] The monarch (king or queen), sitting upon a canopied throne, touched the affected individual, and presented that individual with a coin – usually an Angel, a gold coin the value of which varied from about 6 shillings to about 10 shillings – by pressing it against the affected's neck.[41]

Although the ceremony was of no medical value, members of the royal courts often propagandized that those receiving the royal touch were miraculously healed. André du Laurens, the senior physician of Henry IV, publicized findings that at least half of those that received the royal touch were cured within a few days.[44] The royal touch remained popular into the 18th century. Parish registers from Oxfordshire, England include not only records of baptisms, marriages, and deaths, but also records of those eligible for the royal touch.[40]

Contagion

Girolamo Fracastoro became the first person to propose, in his work De contagione in 1546, that phthisis was transmitted by an invisible virus. Among his assertions were that the virus could survive between two or three years on the clothes of those with the disease and that it was usually transmitted through direct contact or the discharged fluids of the infected, what he called fomes. He noted that phthisis could be contracted without either direct contact or fomes, but was unsure of the process by which the disease propagated across distances.[45]

Paracelsus's tartaric process

Paracelsus advanced the belief that tuberculosis was caused by a failure of an internal organ to accomplish its alchemical duties. When this occurred in the lungs, stony precipitates would develop causing tuberculosis in what he called the tartaric process.[46]

Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

Franciscus Sylvius began differentiating between the various forms of tuberculosis (pulmonary, ganglion). He was the first person to recognize that the skin ulcers caused by scrofula resembled tubercles seen in phthisis,[47] noting that "phthisis is the scrofula of the lung" in his book Opera Medica, published posthumously in 1679. Around the same time, Thomas Willis concluded that all diseases of the chest must ultimately lead to consumption.[48] Willis did not know the exact cause of the disease but he blamed it on sugar[49] or an acidity of the blood.[47] Richard Morton published Phthisiologia, seu exercitationes de Phthisi tribus libris comprehensae in 1689, in which he emphasized the tubercle as the true cause of the disease. So common was the disease at the time that Morton is quoted as saying "I cannot sufficiently admire that anyone, at least after he comes to the flower of his youth, can [sic] dye without a touch of consumption."[50]

In 1720, Benjamin Marten proposed in A New Theory of Consumptions more Especially of Phthisis or Consumption of the Lungs that the cause of tuberculosis was some type of animalcula—microscopic living beings that are able to survive in a new body (similar to the ones described by Anton van Leeuwenhoek in 1695).[51] The theory was roundly rejected and it took another 162 years before Robert Koch demonstrated it to be true.

In 1768, Robert Whytt gave the first clinical description of tuberculosis meningitis[52] and, in 1779, Percivall Pott, an English surgeon, described the vertebral lesions that carry his name.[42] In 1761, Leopold Auenbrugger, an Austrian physician, developed the percussion method of diagnosing tuberculosis,[53] a method rediscovered some years later in 1797 by Jean-Nicolas Corvisart of France. After finding it useful, Corvisart made it readily available to the academic community by translating it into French.[54]

William Stark proposed that ordinary lung tubercles could eventually evolve into ulcers and cavities, believing that the different forms of tuberculosis were simply different manifestations of the same disease. Unfortunately, Stark died at the age of 30 (while studying scurvy) and his observations were discounted.[55] In his Systematik de speziellen Pathologie und Therapie, J. L. Schönlein, Professor of Medicine in Zurich, proposed that the word "tuberculosis" be used to describe the condition of tubercles.[56][57]

The incidence of tuberculosis grew progressively during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, displacing leprosy, peaking between the 18th and 19th century as field workers moved to the cities looking for work.[42] When he released his study in 1808, William Woolcombe was astonished at the prevalence of tuberculosis in 18th-century England.[58] Of the 1,571 deaths in the English city of Bristol between 1790 and 1796, 683 were due to tuberculosis.[59] Remote towns, initially isolated from the disease, slowly succumbed. The consumption deaths in the village of Holycross in Shropshire between 1750 and 1759 were one in six (1:6); ten years later, 1:3. In the metropolis of London, 1:7 died from consumption at the dawn of the 18th century, by 1750 that proportion grew to 1:5.25 and surged to 1:4.2 by around the start of the 19th century.[60] The Industrial Revolution coupled with poverty and squalor created the optimal environment for the propagation of the disease.

Nineteenth century

Epidemic tuberculosis

In the 18th and 19th century, tuberculosis (TB) had become epidemic in Europe, showing a seasonal pattern.[61][62][63][64] In the 18th century, TB had a mortality rate as high as 900 deaths (800–1000) per 100,000 population per year in Western Europe, including in places like London, Stockholm and Hamburg.[61][62][63] Similar death rate occurred in North America.[62] In the United Kingdom, epidemic TB may have peaked around 1750, as suggested by mortality data.[64]

In the 19th century, TB killed about a quarter of the adult population of Europe.[65] In western continental Europe, epidemic TB may have peaked in the first half of the 19th century.[64] In addition, between 1851 and 1910, around four million died from TB in England and Wales – more than one third of those aged 15 to 34 and half of those aged 20 to 24 died from TB.[61] By the late 19th century, 70–90% of the urban populations of Europe and North America were infected with the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and about 80% of those individuals who developed active TB died of it.[66] However, mortality rates began declining in the late 19th century throughout Europe and the United States.[66]

At the time, tuberculosis was called the robber of youth, because the disease had higher death rate among young people.[61][63] Other names included the Great White Plague and the White Death, where the "white" was due to the extreme anaemic pallor of those infected.[61][63][67] In addition, TB has been called by many as the "Captain of All These Men of Death".[61][63][67][68]

A romantic disease

|

"Chopin coughs with infinite grace." |

| —George Sand in a letter to Madame d'Agoult |

It was during this century that tuberculosis was dubbed the White Plague,[69] mal de vivre, and mal du siècle. It was seen as a "romantic disease". Individuals with tuberculosis were thought to have heightened sensitivity. The slow progress of the disease allowed for a "good death" as those affected could arrange their affairs.[70] The disease began to represent spiritual purity and temporal wealth, leading many young, upper-class women to purposefully pale their skin to achieve the consumptive appearance. British poet Lord Byron wrote, "I should like to die from consumption", helping to popularize the disease as the disease of artists.[71] George Sand doted on her phthisic lover, Frédéric Chopin, calling him her "poor melancholy angel".[72]

In France, at least five novels were published expressing the ideals of tuberculosis: Dumas's La Dame aux camélias, Murger's Scènes de la vie de Bohème, Hugo's Les Misérables, the Goncourt brothers' Madame Gervaisais and Germinie Lacerteux, and Rostand's L'Aiglon. The portrayals by Dumas and Murger in turn inspired operatic depictions of consumption in Verdi's La traviata and Puccini's La bohème. Even after medical knowledge of the disease had accumulated, the redemptive-spiritual perspective of the disease has remained popular[73] (as seen in the 2001 film Moulin Rouge based in part on La traviata and the musical adaptations of Les Misérables).

In large cities the poor had high rates of tuberculosis. Public-health physicians and politicians typically blamed both the poor themselves and their ramshackle tenement houses (conventillos) for the spread of the dreaded disease. People ignored public-health campaigns to limit the spread of contagious diseases, such as the prohibition of spitting on the streets, the strict guidelines to care for infants and young children, and quarantines that separated families from ill loved ones.[74]

Scientific advances

Though removed from the cultural movement, the scientific understanding advanced considerably. By the end of the 19th century, several major breakthroughs gave hope that a cause and cure might be found.

One of the most important physicians dedicated to the study of phthisiology was René Laennec, who died from the disease at the age of 45, after contracting tuberculosis while studying contagious patients and infected bodies.[75] Laennec invented the stethoscope[53] which he used to corroborate his auscultatory findings and prove the correspondence between the pulmonary lesions found on the lungs of autopsied tuberculosis patients and the respiratory symptoms seen in living patients. His most important work was Traité de l'Auscultation Médiate which detailed his discoveries on the utility of pulmonary auscultation in diagnosing tuberculosis. This book was promptly translated into English by John Forbes in 1821; it represents the beginning of the modern scientific understanding of tuberculosis.[72] Laennec was named professional chair of Hôpital Necker in September 1816 and today he is considered the greatest French clinician.[76][77]

Laennec's work put him in contact with the vanguard of the French medical establishment, including Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis. Louis would go on to use statistical methods to evaluate the different aspects of the disease's progression, the efficacy of various therapies and individuals' susceptibility, publishing an article in the Annales d'hygiène publique entitled "Note on the Relative Frequency of Phthisis in the Two Sexes".[78] Another good friend and co-worker of Laennec, Gaspard Laurent Bayle, published an article in 1810 entitled Recherches sur la Pthisie Pulmonaire, in which he divided pthisis into six types: tubercular phthisis, glandular phthisis, ulcerous phthisis, phthisis with melanosis, calculous phthisis, and cancerous phthisis. He based his findings on more than 900 autopsies.[69][79]

In 1869, Jean Antoine Villemin demonstrated that the disease was indeed contagious, conducting an experiment in which tuberculous matter from human cadavers was injected into laboratory rabbits, which then became infected.[80]

On 24 March 1882, Robert Koch revealed the disease was caused by an infectious agent.[72] In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered the X-ray, which allowed physicians to diagnose and track the progression of the disease,[81] and although an effective medical treatment would not come for another fifty years, the incidence and mortality of tuberculosis began to decline.[82]

| 19th-century tuberculosis mortality rate for New York and New Orleans[83] | |||||

| Deaths/Year/1000 people | |||||

| Year | Population | White people | Black people | ||

| 1821 | New York City | 5.3 | 9.6 | ||

| 1830 | New York City | 4.4 | 12.0 | ||

| 1844 | New York City | 3.6 | 8.2 | ||

| 1849 | New Orleans | 4.9 | 5.2 | ||

| 1855 | New York City | 3.1 | 12.0 | ||

| 1860 | New York City | 2.4 | 6.7 | ||

| 1865 | New York City | 2.8 | 6.7 | ||

| 1880 | New Orleans | 3.3 | 6.0 | ||

| 1890 | New Orleans | 2.5 | 5.9 | ||

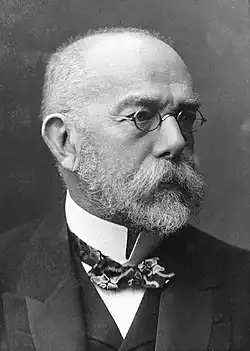

Robert Koch

Villemin's experiments had confirmed the contagious nature of the disease and had forced the medical community to accept that tuberculosis was indeed an infectious disease, transmitted by some etiological agent of unknown origin. In 1882, Prussian physician Robert Koch utilized a new staining method and applied it to the sputum of tuberculosis patients, revealing for the first time the causal agent of the disease: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or Koch's bacillus.[84]

When he began his investigation, Koch knew of the work of Villemin and others who had continued his experiments like Julius Conheim and Carl Salmosen. He also had access to the "pthisis ward" at the Berlin Charité Hospital.[85] Before he confronted the problem of tuberculosis, he worked with the disease caused by anthrax and had discovered the causal agent to be Bacillus anthracis. During this investigation he became friends with Ferdinand Cohn, the director of the Institute of Vegetable Physiology. Together they worked to develop methods of culturing tissue samples. 18 August 1881, while staining tuberculous material with methylene blue, he noticed oblong structures, though he was not able to ascertain whether it was just a result of the coloring. To improve the contrast, he decide to add Bismarck Brown, after which the oblong structures were rendered bright and transparent. He improved the technique by varying the concentration of alkali in the staining solution until the ideal viewing conditions for the bacilli was achieved.

After numerous attempts he was able to incubate the bacteria in coagulated blood serum at 37 degrees Celsius. He then inoculated laboratory rabbits with the bacteria and observed that they died while exhibiting symptoms of tuberculosis, proving that the bacillus, which he named tuberculosis bacillus, was in fact the cause of tuberculosis.[86]

He made his result public at the Physiological Society of Berlin on 24 March 1882, in a famous lecture entitled Über Tuberculose, which was published three weeks later. Since 1882, 24 March has been known as World Tuberculosis Day.[87]

On 20 April 1882, Koch presented an article entitled Die Ätiologie der Tuberculose in which he demonstrated that Mycobacterium was the single cause of tuberculosis in all of its forms.[86]

In 1890 Koch developed tuberculin, a purified protein derivative of the bacteria.[88] Data on experimental inquiry published in Deutsche Landwirthschafts-Zeitung provided immediate practical industry benefits in the form of the Tuberculin test as an aide to diagnosis in both sick and healthy cattle.[89] Tuberculin proved to be an ineffective means of immunization but in 1908, Charles Mantoux found it was an effective intradermic test for diagnosing tuberculosis.[90][91]

If the importance of a disease for mankind is measured from the number of fatalities which are due to it, then tuberculosis must be considered much more important than those most feared infectious diseases, plague, cholera, and the like. Statistics have shown that 1/7 of all humans die of tuberculosis.

— Die Ätiologie der Tuberculose, Robert Koch (1882)

Sanatorium movement

_-_Aibonito_Municipality%252C_Tuberculosis_Sanatorium.jpg.webp)

The advancement of scientific understanding of tuberculosis, and its contagious nature created the need for institutions to house affected individuals.

The first proposal for a tuberculosis facility was made in paper by George Bodington entitled An essay on the treatment and cure of pulmonary consumption, on principles natural, rational and successful in 1840. In this paper, he proposed a dietary, rest, and medical care program for a hospital he planned to found in Maney.[92] Attacks from numerous medical experts, especially articles in The Lancet, disheartened Bodington and he turned to plans for housing the insane.[93]

Around the same time in the United States, in late October and early November 1842, Dr. John Croghan, the owner of Mammoth Cave, brought 15 tuberculosis patients into the cave in the hope of curing the disease with the constant temperature and purity of the cave air.[94] Patients were lodged in stone huts, and each was supplied with a slave to bring meals.[95] One patient, A. H. P. Anderson, wrote glowing reviews of the cave experience:[96]

[S]ome of the invalids eat at their pavillions while others in better health attend regularly the table d'hote which is very good indeed, having a considerable variety and being almost daily (I've noted but 2–3 omissions) graced with a saddle of venison or other game.

— A. H. P. Anderson

By late January, early February 1843, two patients were dead and the rest had left. Departing patients died anywhere from three days to three weeks after resurfacing; John Croghan died of tuberculosis at his Louisville residence in 1849.[97]

Hermann Brehmer, a German physician, was convinced that tuberculosis arose from the difficulty of the heart to correctly irrigate the lungs. He therefore proposed that regions well above sea level, where the atmospheric pressure was less, would help the heart function more effectively. With the encouragement of explorer Alexander von Humboldt and his teacher J. L. Schönlein, the first anti-tuberculosis sanatorium was established in 1854, 650 meters above sea level, at Görbersdorf.[98] Three years later he published his findings in a paper Die chronische Lungenschwindsucht und Tuberkulose der Lunge: Ihre Ursache und ihre Heilung.

Brehmer and one of his patients, Peter Dettweiler, became proponents for the sanatorium movement, and by 1877, sanatoriums began to spread beyond Germany and throughout Europe. Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau subsequently founded the Adirondack Cottage Sanitorium in Saranac Lake, New York in 1884. One of Trudeau's early patients was author Robert Louis Stevenson; his fame helped establish Saranac Lake as a center for the treatment of tuberculosis. In 1894, after a fire destroyed Trudeau's small home laboratory, he organized the Saranac Laboratory for the Study of Tuberculosis; renamed the Trudeau Institute, the laboratory continues to study infectious diseases.[99]

Peter Dettweiler went on to found his own sanatorium at Falkenstein in 1877 and in 1886 published findings claiming that 132 of his 1022 patients had been completely cured after staying at his institution.[100] Eventually, sanatoriums began to appear near large cities and at low altitudes, like the Sharon Sanatorium in 1890 near Boston.[101]

Sanatoriums were not the only treatment facilities. Specialized tuberculosis clinics began to develop in major metropolitan areas. Sir Robert Philip established the Royal Victoria Dispensary for Consumption in Edinburgh in 1887. Dispensaries acted as special sanatoriums for early tuberculosis cases and were opened to lower income individuals. The use of dispensaries to treat middle and lower-class individuals in major metropolitan areas and the coordination between various levels of health services programs like hospitals, sanatoriums, and tuberculosis colonies became known as the "Edinburgh Anti-tuberculosis Scheme".[102]

Twentieth century

Containment

At the beginning of the 20th century, tuberculosis was one of the UK's most urgent health problems. A royal commission was set up in 1901, The Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Relations of Human and Animal Tuberculosis. Its remit was to find out whether tuberculosis in animals and humans was the same disease, and whether animals and humans could infect each other. By 1919, the Commission had evolved into the UK's Medical Research Council.

In 1902, the International Conference on Tuberculosis convened in Berlin. Among various other acts, the conference proposed the Cross of Lorraine be the international symbol of the fight against tuberculosis. National campaigns spread across Europe and the United States to tamp down on the continued prevalence of tuberculosis.

After the establishment in the 1880s that the disease was contagious, TB was made a notifiable disease in Britain; there were campaigns to stop spitting in public places, and the infected poor were pressured to enter sanatoria that resembled prisons; the sanatoria for the middle and upper classes offered excellent care and constant medical attention.[103] Whatever the purported benefits of the fresh air and labor in the sanatoria, even under the best conditions, 50% of those who entered were dead within five years (1916).[103]

The promotion of Christmas Seals began in Denmark during 1904 as a way to raise money for tuberculosis programs. It expanded to the United States and Canada in 1907–1908 to help the National Tuberculosis Association (later called the American Lung Association).

In the United States, concern about the spread of tuberculosis played a role in the movement to prohibit public spitting except into spittoons.

Vaccines

The first genuine success in immunizing against tuberculosis was developed from attenuated bovine-strain tuberculosis by Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin in 1906. It was called "BCG" (Bacille Calmette-Guérin). The BCG vaccine was first used on humans in 1921 in France,[104] but it was not until after World War II that BCG received widespread acceptance in Great Britain, and Germany.[105] In the early days of the British National Health Service X-ray examination for TB increased dramatically but rates of vaccination were initially very low. In 1953 it was agreed that secondary school pupils should be vaccinated, but by the end of 1954 only 250,000 people had been vaccinated. By 1956 this had risen to 600,000, about half being school children.[106]

In Italy, Salvioli's diffusing vaccine (Vaccino Diffondente Salvioli; VDS) was used from 1948 until 1976. It was developed by Professor Gaetano Salvioli (1894–1982) of the University of Bologna.

Treatments

As the century progressed, some surgical interventions, including the pneumothorax or plombage technique—collapsing an infected lung to "rest" it and allow the lesions to heal—were used to treat tuberculosis.[107] Pneumothorax was not a new technique by any means. In 1696, Giorgio Baglivi reported a general improvement in tuberculosis patients after they received sword wounds to the chest. F.H. Ramadge induced the first successful therapeutic pneumothorax in 1834, and reported subsequently the patient was cured. It was in the 20th century, however, that scientists sought to rigorously investigate the effectiveness of such procedures. Carlo Forlanini experimented with his artificial pneumothorax technique from 1882 to 1888 and this started to be followed only years later.[108] In 1939, the British Journal of Tuberculosis published a study by Oli Hjaltested and Kjeld Törning on 191 patients undergoing the procedure between 1925 and 1931; in 1951, Roger Mitchell published several articles on the therapeutic outcomes of 557 patients treated between 1930 and 1939 at Trudeau Sanatorium in Saranac Lake.[109] The search for a medicinal cure, however, continued in earnest.

During the Nazi occupation of Poland, SS-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm Koppe organized the execution of more than 30,000 Polish patients with tuberculosis – little knowing or caring that a cure was nearly at hand. In Canada, doctors continued to surgically remove TB in the indigenous patients during the 1950s and 60s, even though the procedure was no longer performed on non-Indigenous patients.[110][111]

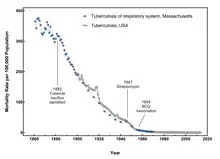

In 1944 Albert Schatz, Elizabeth Bugie, and Selman Waksman isolated streptomycin produced by a bacterial strain Streptomyces griseus. Streptomycin was the first effective antibiotic against M. tuberculosis.[112] This discovery is generally considered the beginning of the modern era of tuberculosis.[112] Para-aminosalicylic acid, discovered in 1946, was used in combination with Streptomycin to reduce the emergence of drug resistant variants, which greatly improved patient outcomes.[113] The true revolution began some years later, in 1952, with the development of isoniazid, the first oral mycobactericidal drug.[112] The advent of rifampin in the 1970s hastened recovery times, and significantly reduced the number of tuberculosis cases until the 1980s.

The British epidemiologist Thomas McKeown had shown that "treatment by streptomycin reduced the number of deaths since it was introduced (1948–71) by 51 per cent...".[114] However, he also showed that the mortality from TB in England and Wales had already declined by 90 to 95% before streptomycin and BCG-vaccination were widely available, and that the contribution of antibiotics to the decline of mortality from TB was actually very small: '...for the total period since cause of death was first recorded (1848–71) the reduction was 3.2 per cent'.[114]: 82 These figures have since been confirmed for all western countries (see for example the decline in TB mortality in the USA) and for all then known infectious diseases. McKeown explained the decline in mortality from infectious diseases by an improved standard of living, particularly by better nutrition, and by better hygiene, and less by medical intervention. McKeown, who is considered as the father of social medicine,[115] has advocated for many years, that with drugs and vaccines we may win the battle but will lose the war against Diseases of Poverty.[116] Thereto, efforts and resources should be primarily directed toward improving the standard of living of people in low resource countries, and toward improving their environment by providing clean water, sanitation, better housing, education, safety and justice, and access to medical care. Particularly the work of Nobel laureates Robert W. Fogel (1993)[117][118][119][120] and Angus Deaton (2015)[115] have greatly contributed to the recent reappreciation of the McKeown thesis. A negative confirmation of the McKeown thesis was that increased pressure on wages by IMF loans to post-communist Eastern Europe were strongly associated with a rise in TB incidence, prevalence and mortality.[121]

In the United States there was dramatic reduction in tuberculosis cases by the 1970s. As early as the 1900s, public health campaigns were launched to educate people about the contagion. In later decades, posters, pamphlets and newspapers continued to inform people about the risk of contagion and methods to avoid it, including increasing public awareness about the importance of good hygiene. Though improved awareness of good hygiene practices reduced the number of cases, the situation was worse in the poor neighborhoods. Public clinics were set up to improve awareness and provide screenings. In Scotland, Dr Nora Wattie led the public health innovations both at local[122] and national level.[123] This resulted in sharp declines through the 1920s and 1930s.[124]

Tuberculosis resurgence

Hopes that the disease could be completely eliminated were dashed in the 1980s with the rise of drug-resistant strains. Tuberculosis cases in Britain, numbering around 117,000 in 1913, had fallen to around 5,000 in 1987, but cases rose again, reaching 6,300 in 2000 and 7,600 cases in 2005.[125] Due to the elimination of public health facilities in New York and the emergence of HIV, there was a resurgence of TB in the late 1980s.[126] The number of patients failing to complete their course of drugs was high. New York had to cope with more than 20,000 TB patients with multidrug-resistant strains (resistant to, at least, both rifampin and isoniazid).

In response to the resurgence of tuberculosis, the World Health Organization issued a declaration of a global health emergency in 1993.[127] Every year, nearly half a million new cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) are estimated to occur worldwide.[128]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carl Zimmer, "Tuberculosis Is Newer Than Thought, Study Says" Archived 16 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, 21 August 2014

- 1 2 Hershkovitz, Israel; Donoghue, Helen D.; Minnikin, David E.; Besra, Gurdyal S.; Lee, Oona Y-C.; Gernaey, Angela M.; Galili, Ehud; Eshed, Vered; Greenblatt, Charles L. (15 October 2008). "Detection and Molecular Characterization of 9000-Year-Old Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithic Settlement in the Eastern Mediterranean". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3426. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3426H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003426. PMC 2565837. PMID 18923677.

- ↑ Wirth T.; Hildebrand F.; et al. (2008). "Origin, spread and demography of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex". PLOS Pathog. 4 (9): e1000160. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000160. PMC 2528947. PMID 18802459.

- ↑ Roberts, Charlotte A.; Pfister, Luz-Andrea; Mays, Simon (1 July 2009). "Letter to the editor: Was tuberculosis present in Homo erectus in Turkey?". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (3): 442–444. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21056. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 19358292.

- 1 2 "Sea Lions And Seals Likely Spread Tuberculosis To Ancient Peruvians", National Public Radio, 21 Aug 2014 Archived 8 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ φθίσις. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Hershkovitz I.; Donoghue H. D.; et al. (2008). "Detection and molecular characterization of 9,000-year-old Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithic settlement in the Eastern Mediterranean". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3426. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3426H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003426. PMC 2565837. PMID 18923677.

- ↑ Madkour 2004:3

- ↑ Zink 2003:359-67

- ↑ Madkour 2004:6

- ↑ Madkour 2004:11–12

- ↑ Deuteronomy 28:22

- ↑ Zysk 1998:12

- ↑ Zysk 1998:32

- 1 2 Ghose 2003:214

- ↑ 2014: 586, 301–302.

- ↑ 2014: 154.

- ↑ 2014: 13.

- ↑ Elvin et al. 1998:521-2

- ↑ 25-158, tr. Unschuld and Tessenow 2001: 420–421.

- ↑ tr. 2001: 421.

- ↑ Yang 1998:xiii

- ↑ 1/17a-b, tr. Liu 1971: 298.

- ↑ tr. Liu 1971: 287.

- ↑ Liu 1971: 287–8.

- ↑ 23/1a-b, tr. Liu 1971: 288.

- ↑ Liu 1971: 200.

- ↑ Liu 1971: 290.

- ↑ tr. Liu 1971: 289.

- ↑ 1971: 289.

- ↑ Hippocrates, Of the Epidemics 1.i.2 Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Herzog 1998:5

- ↑ McClelland 1909:403–404

- ↑ Vitruvius, On Architecture 1.6.3 Archived 22 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Aretaeus, De causis et signis diuturnorum morborum On Phthisis Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Stivelman 1931:128

- ↑ Bos, Kirsten I.; Harkins, Kelly M.; Herbig, Alexander; Coscolla, Mireia; et al. (20 August 2014). "Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis". Nature. 514 (7523): 494–7. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..494B. doi:10.1038/nature13591. PMC 4550673. PMID 25141181.

- 1 2 Prat 2003:153

- ↑ Radloff: "Bussgebete" stb. 874. 1 jegyzet.

- 1 2 Maulitz and Maulitz 1973:87

- 1 2 3 Dang 2001:231

- 1 2 3 Aufderheide 1998:129

- ↑ Mitchinson, John; Molly Oldfield (9 January 2009). "QI: Quite Interesting facts about Kings". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Gosman 2004:140

- ↑ Brock Milestones 1999:72

- ↑ Debus 2001:13

- 1 2 Ancell 1852:549

- ↑ Waksman 1964:34

- ↑ Macinnis 2002:165

- ↑ Otis 1920:28

- ↑ Daniel 2000:8

- ↑ Whytt 1768:46

- 1 2 Daniel 2000:45

- ↑ Dubos 1987:79

- ↑ Dubos 1987:83

- ↑ Dubos 1987:84

- ↑ Herzog 1998:7

- ↑ Chalke 1959:92

- ↑ Chalke 1959:92-3

- ↑ Chalke 1959:93

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frith, John. "History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague". Journal of Military and Veterans' Health. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 Daniel, Thomas M. (1 November 2006). "The history of tuberculosis". Respiratory Medicine. 100 (11): 1862–1870. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.006. ISSN 0954-6111. PMID 16949809.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barberis, I.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Galluzzo, L.; Martini, M. (March 2017). "The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 58 (1): E9–E12. ISSN 1121-2233. PMC 5432783. PMID 28515626.

- 1 2 3 Zürcher, Kathrin; Zwahlen, Marcel; Ballif, Marie; Rieder, Hans L.; Egger, Matthias; Fenner, Lukas (5 October 2016). "Influenza Pandemics and Tuberculosis Mortality in 1889 and 1918: Analysis of Historical Data from Switzerland". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0162575. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1162575Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162575. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5051959. PMID 27706149.

- ↑ "The Next Pandemic – Tuberculosis: The Oldest Disease of Mankind Rising One More Time". British Journal of Medical Practitioners. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- 1 2 "Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800-1922". Harvard University Library. 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- 1 2 Daniel, Thomas M. (1997). Captain of death: the story of tuberculosis. Rochester, NY, USA: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-878822-96-3. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ↑ Rubin, S. A. (July 1995). "Tuberculosis. Captain of all these men of death". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 33 (4): 619–639. doi:10.1016/S0033-8389(22)00609-1. ISSN 0033-8389. PMID 7610235.

- 1 2 Madkour 2004:20

- ↑ Bourdelais 2006:15

- ↑ Yancey 2007:18

- 1 2 3 Daniel 2006:1864

- ↑ Barnes 1995:51

- ↑ Diego Armus, The Ailing City: Health, Tuberculosis, and Culture in Buenos Aires, 1870–1950 (2011)

- ↑ Daniel 2000:60

- ↑ Daniel 2000:44

- ↑ Ackerknecht 1982:151

- ↑ Barnes 1995:39

- ↑ Porter 2006:154

- ↑ Barnes 1995:41

- ↑ Shorter 1991:88

- ↑ Aufderheide 1998:130

- ↑ Daniel 2004:159

- ↑ Brock Robert Koch 1999:120

- ↑ Brock Robert Koch 1999:118

- 1 2 Koch 1882

- ↑ Yancey 2007:1982

- ↑ Magner 2002:273

- ↑ Tuberculosis In European Countries, The Times, 25 February 1895

- ↑ Madkour 2004:49

- ↑ Kolchinsky 2013.

- ↑ Bodington 1840

- ↑ Dubos 1987:177

- ↑ Kentucky: Mammoth Cave long on history. Archived 13 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine CNN. 27 February 2004. Accessed 8 October 2006.

- ↑ Billings, Hillman, and Regen 1957:12

- ↑ qtd. in Billings, Hillman, and Regen 1957:13

- ↑ Billings, Hillman, and Regen 1957:14

- ↑ Dubos 1987:175–176

- ↑ Donaldson, Alfred L., A History of the Adirondacks, Century Co., New York 1921 (reprinted by Purple Mountain Press, Fleischmanns, NY, 1992), pp. 243–265

- ↑ Graham 1893:266

- ↑ Shryock 1977:47

- ↑ "The Edinburgh Scheme" 1914:117

- 1 2 McCarthy 2001:413-7

- ↑ Bonah 2005:696–721

- ↑ Comstock 1994:528-40

- ↑ Webster, Charles (1988). The Health Services Since the War. London: HMSO. p. 323. ISBN 978-0116309426.

- ↑ Wolfart 1990:506–11

- ↑ Hansson, Nils; Polianski, Igor J. (August 2015). "Therapeutic Pneumothorax and the Nobel Prize". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 100 (2): 761–765. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.100. PMID 26234863.

- ↑ Daniel 2006:1866

- ↑ Blackburn, Mark (24 July 2013). "First Nation infants subject to "human experimental work" for TB vaccine in 1930s-40s". APTN News. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ "Canada's Residential Schools: The History, Part 2, 1939 to 2000: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Volume 1" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 1 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Daniel 2006:1868

- ↑ Snider, Gordon (1 December 1997). "Tuberculosis Then and Now: A Personal Perspective on the Last 50 Years". Annals of Internal Medicine. 126 (3). doi:10.7326/0003-4819-126-3-199702010-00011.

- 1 2 McKeown, Thomas (1976). The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage or Nemesis? (The Rock Carlington Fellow, 1976). London, UK: Nuffield Provincial Hospital Trust. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-900574-24-5. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- 1 2 Deaton, Angus (2013). The Great Escape. Health, wealth, and the origins of inequality. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. pp. 91–93. ISBN 978-0-691-15354-4.

McKeown's views, updated to modern circumstances, are still important today in debates between those who think that health is primarily determined by medical discoveries and medical treatment and those who look to the background social conditions of life.

- ↑ McKeown, Thomas (1988). Diseases of Poverty (Chapter 8) In: The Origins of Human Disease. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. pp. 181–199. ISBN 978-0-631-17938-2.

- ↑ Fogel, R. W. (2004). "Technophysio evolution and the measurement of economic growth". Journal of Evolutionary Economics. 14 (2): 217–21. doi:10.1007/s00191-004-0188-x. S2CID 154777833.

- ↑ Fogel, Robert (2004). The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100: Europe, America, and the Third World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 189 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-80878-1.

- ↑ Fogel, Robert; Roderick Floud; Bernard Harris; Sok Chul Hong (2011). The Changing Body: Health, Nutrition, and Human Development in the Western World since 1700. New York: Cambridge University Press, New York. ISBN 978-0-521-87975-0.

- ↑ Fogel, Robert W. (2012). Explaining Long-Term Trends in Health and Longevity. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02791-6.

- ↑ Stuckler, David; Lawrence P King; Sanjay Basu (22 July 2008). "International Monetary Fund programs and tuberculosis outcomes in post-communist countries". PLOS Medicine. 5 (7): e143. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050143. PMC 2488179. PMID 18651786.

- ↑ "Watch Your Health". Motherwell Times. 26 November 1913. p. 3.

- ↑ "Solving the problems of adolescence, Conference of National Council of Girls' Clubs, Growth of Nervous Diseases". The Scotsman. 10 July 1939. p. 13.

- ↑ "TB in America: 1895-1954 | American Experience | PBS". PBS. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis — Respiratory and Non-respiratory Notifications, England and Wales, 1913–2005". Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections. 21 March 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ↑ Paolo and Nosanchuk 2004:287–93

- ↑ World Health Organization (WHO). Frequently asked questions about TB and HIV. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ↑ Health ministers to accelerate efforts against drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization.

References

Books

- Ackerknecht, Erwin Heinz (1982). A Short History of Medicine. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0471067627.

- Armus, Diego. The Ailing City: Health, Tuberculosis, and Culture in Buenos Aires, 1870–1950 (2011)

- Aufderheide, Arthur C.; Conrado Rodriguez-Martin; Odin Langsjoen (1998). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521552035.

- Barnes, David S. (1995). The Making of a Social Disease: Tuberculosis in Nineteenth-century France. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520087729.

- Bourdelais, Patrice; Bart K. Holland (2006). Epidemics Laid Low: A History of what Happened in Rich Countries. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801882944.

- Brock, Thomas D. (1999). Milestones in Microbiology 1546 to 1940. ASM Press.

- Brock, Thomas d. (1999). Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. ASM Press. ISBN 978-0910239196.

- Bryder, Linda. Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth-Century Britain (1988), 298p.

- Daniel, Thomas M. (2000). Pioneers of Medicine and Their Impact on Tuberculosis. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1580460675.

- Dubos, Rene Jules; Jean Dubos (1987). The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. Rutgers University Press.

- Debus, Allen G. (2001). Chemistry and Medical Debate: Van Helmont to Boerhaave. Science History Publications. ISBN 978-0881352924.

- Elvin, Mark; Cuirong Liu; Tsʻui-jung Liu (1998). Sediments of Time: Environment and Society in Chinese History. Cambridge University Press.

- Ghose, Tarun K.; P. Ghosh; S K Basu (2003). Biotechnology in India. Springer. ISBN 9783540364887.

- Gosman, Martin; Alasdair A. MacDonald; Arie Johan Vanderjagt (2003). Princes and Princely Culture, 1450–1650: 1450 – 1650. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004135727.

- Macinnis, Peter (2002). Bittersweet: The Story of Sugar. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1865086576.

- McMillen, Christian W. Discovering Tuberculosis: A Global History, 1900 to the Present (2014)

- Madkour, M. Monir; D. A. Warrell (2004). Tuberculosis. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3540014416.

- Magner, Lois N. (2002). A History of the Life Sciences. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0824789428.

- Otis, Edward Osgood (1920). Pulmonary tuberculosis. W.M. Leonard.

- Porter, Roy (2006). The Cambridge History of Medicine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521557917.

- Reber, Vera Blinn. Tuberculosis in the Americas, 1870-1945: Beneath the Anguish in Philadelphia and Buenos Aires (Routledge, 2018) online review Archived 18 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Ryan, Frank (1992). Tuberculosis: The Greatest Story Never Told. Swift Publishers, England. ISBN 1-874082-00-6. 446 + xxiii pages.

- Shorter, Edward (1991). Doctors and Their Patients: A Social History. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0887388712.

- Shryock, Richard Harrison (1988). National Tuberculosis Association, 1904-1954: A Study of the Voluntary Health Movement in the United States. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0405098314.

- Smith, F. B. Retreat of Tuberculosis, 1850-1950 (1988) 271p

- Waksman, Selman A. (1964). The Conquest of Tuberculosis. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles.

- Yancey, Diane (2007). Tuberculosis. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0761316244.

- Zysk, Kenneth G. (1998). Medicine in the Veda: Religious Healing in the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-8120814004.

- Kolchinsky, Anna (2013). Tuberculosis as Disease and Politics in Germany, 1871-1961 (PhD thesis). Boston College. Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

Older studies

- Ancell, Henry (1852). A Treatise on Tuberculosis: The Constitutional Origin of Consumption and Scrofula. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans.

- Bodington, George (1840). An Essay on the Treatment and Cure of Pulmonary Consumption: On Principles Natural, Rational, and Successful; with Suggestions for an Improved Plan of Treatment of the Disease Amongst the Lower Classes of Society. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans.

- Unschuld, Paul U. and Hermann Tessenow (2011), Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: An Annotated Translation of Huang Di's Inner Classic – Basic Questions, University of California Press.

- Whytt, R (1768). Observations on the Dropsy in the Brain. Edinburgh: Balfour, Auld & Smellie.

- Yang, Shou-zhong; Bob Flaws (1998). The Divine Farmer's Materia Medica: A Translation of the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing. Blue Poppy Enterprises, Inc.

- Zhang Zhibin and Paul U. Unschuld (2014), Dictionary of the Ben cao gang mu, Volume 1: Chinese Historical Illness Terminology, University of California Press.

Journals

- Billings FT, Hillman JW, Regen EM (1957). "Spleleologic Management of Consumption in Mammoth Cave. An Early Effort in Climatologic Therapy". Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 68: 10–15. PMC 2248950. PMID 13486602.

- Bonah C (2005). "The 'experimental stable' of the BCG vaccine: safety, efficacy, proof, and standards, 1921–1933". Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci. 36 (4): 696–721. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2005.09.003. PMID 16337557.

- Chalke HD (1959). "Some historical aspects of tuberculosis". Public Health. 74 (3): 83–95. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(59)80055-X. PMID 13809031.

- Comstock G (1994). "The International Tuberculosis Campaign: a pioneering venture in mass vaccination and research". Clin Infect Dis. 19 (3): 528–40. doi:10.1093/clinids/19.3.528. PMID 7811874.

- Daniel T (2004). "The impact of tuberculosis on civilization". Infect Dis Clin N Am. 18 (1): 157–65. doi:10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00096-5. PMID 15081511.

- Egedesø, Peter Juul, Casper Worm Hansen, Peter Sandholt Jensen. 2020. "Preventing the White Death: Tuberculosis Dispensaries." The Economic Journal

- Graham JE (1893). "The Treatment of Tuberculosis". The Montreal Medical Journal. Montreal: Gazette Printing Co. 21: 253–273.

- Henius, Kurt; Basch, Erich (25 December 1925). "Erfahrungen mit dem Tuberkulomuzin Weleminsky (Experiences with tuberculomuzin Weleminsky)" (PDF). Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 51 (52): 2149–2150. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1137468. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- Koch R (10 April 1882). "Die Ätiologie der Tuberculose". Berliner Klinischen Wochenschrift. 15: 221–230.

- Jones Susan D (2004). "Mapping a zoonotic disease: Anglo-American efforts to control bovine tuberculosis before World War I.". Osiris. 19: 133–148. doi:10.1086/649398. PMID 15478271. S2CID 37917248.

- Liu Ts'un-yan 柳存仁 (1971), "The Taoists' Knowledge of Tuberculosis in the Twelfth Century", T'oung Pao 57.5, 285-301.

- Maulitz RC, Maulitz SR (1973). "The King's Evil in Oxfordshire". Med Hist. 17 (1): 87–89. doi:10.1017/s0025727300018251. PMC 1081423. PMID 4595538.

- McCarthy OR (2001). "The key to the sanatoria". J R Soc Med. 94 (8): 413–7. doi:10.1177/014107680109400813. PMC 1281640. PMID 11461990.

- McClelland C (September 1909). "Galen on Tuberculosis". The Physician and Surgeon. 31: 400–404.

- Paolo W, Nosanchuk J (2004). "Tuberculosis in New York city: recent lessons and a look ahead". Lancet Infect Dis. 4 (5): 287–93. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01004-7. PMID 15120345.

- Prat JG; SMFM Souza (2003). "Prehistoric Tuberculosis in America: Adding Comments to a Literature Review". Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 98 (Suppl. I): 151–159. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762003000900023. PMID 12687776.

- Stivelman B (1931). "Address on tuberculosis". J Natl Med Assoc. 23 (3): 128–30.

- Waddington Keir (2003). "'Unfit for human consumption': Tuberculosis and the problem of infected meat in late Victorian Britain". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 77 (3): 636–661. doi:10.1353/bhm.2003.0147. PMID 14523263. S2CID 26858215.

- Wilson Leonard G (1990). "The historical decline of tuberculosis in Europe and America: its causes and significance". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 45 (3): 366–396. doi:10.1093/jhmas/45.3.366. PMID 2212609.

- Wolfart W (1990). "Surgical treatment of tuberculosis and its modifications—collapse therapy and resection treatment and their present-day sequelae". Offentl Gesundheitswes. 52 (8–9): 506–11. PMID 2146567.

- Zink A, Sola C, Reischl U, Grabner W, Rastogi N, Wolf H, Nerlich A (2003). "Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex DNAs from Egyptian Mummies by Spoligotyping". J Clin Microbiol. 41 (1): 359–67. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.1.359-367.2003. PMC 149558. PMID 12517873.

- Gernaey, Angela M.; Minnikin, David E.; Copley, Mike S.; Power, Jacinda J.; Ahmed, Ali M.S.; Dixon, Ronald A.; Roberts, Charlotte A.; Robertson, Duncan J.; Nolan, John; Chamberlain, Andrew (1998). "Detecting Ancient Tuberculosis". Internet Archaeology (5). doi:10.11141/ia.5.3.

- "The Edinburgh Anti=Tuberculosis Scheme" (PDF). The British Journal of Nursing. 52: 117. 7 January 1914. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

Conferences

- Dang B (23–24 March 2001). "The Royal Touch". The Proceedings of the 10th Annual History of Medicine Days. Calgary, AB. pp. 229–34.