Tiagabine

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /taɪˈæɡəbiːn/ |

| Trade names | Gabitril |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Epilepsy[1] |

| Side effects | Tiredness, sleepiness, nausea, irritability, pain, trouble sleeping[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets) |

| Typical dose | 15 to 45 mg/day[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Tiagabine |

| MedlinePlus | a698014 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 90–95%[3] |

| Protein binding | 96%[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP450 system,[3] primarily CYP3A)[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 5–8 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Fecal (63%) and kidney (25%)[4] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

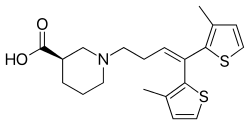

| Formula | C20H25NO2S2 |

| Molar mass | 375.55 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Tiagabine, sold under the brand name Gabitril, is a medication primarily used to treat epilepsy.[1] Specifically it is used for partial seizure that are not controllable by other measures.[1] Use for other disorders is discouraged.[1] It is taken by mouth, usually with food in divided doses over the day, starting at a small dose and increased gradually.[6]

Common side effects include tiredness, sleepiness, nausea, irritability, pain, and trouble sleeping.[1] In certain types of epilepsy, it may increase seizure frequency.[2] Other side effects may include suicide and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.[1] While safety in pregnancy is unclear, there are concerns it may harm the baby.[1] It is believed to work by affecting γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[1]

Tiagabine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1997.[1] In the United Kingdom 100 tablets of 10 mg costs the NHS about £104 as of 2021.[2] This amount in the United States costs about 300 USD.[7][8]

Medical uses

Tiagabine is approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an adjunctive treatment for partial seizures in individuals of age 12 and up. It may also be prescribed off-label by physicians to treat anxiety disorders and panic disorder as well as neuropathic pain (including fibromyalgia). For anxiety and neuropathic pain, tiagabine is used primarily to augment other treatments. Tiagabine may be used alongside selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, or benzodiazepines for anxiety, or antidepressants, gabapentin, other anticonvulsants, or opioids for neuropathic pain.[9]

Dosage

It is generally started at 5 to 10 mg per day and increased to 15 to 45 mg per day.[2]

Side effects

The most common side effect of tiagabine is dizziness.[10] Other side effects that have been observed with a rate of statistical significance relative to placebo include asthenia, somnolence, nervousness, memory impairment, tremor, headache, diarrhea, and depression.[10][11] Adverse effects such as confusion, aphasia (difficulty speaking clearly)/stuttering, and paresthesia (a tingling sensation in the body's extremities, particularly the hands and fingers) may occur at higher dosages of the drug (e.g., over 8 mg/day).[10] Tiagabine may induce seizures in those without epilepsy, particularly if they are taking another drug which lowers the seizure threshold.[9] There may be an increased risk of psychosis with tiagabine treatment, although data is mixed and inconclusive.[3][12] Tiagabine can also reportedly interfere with visual color perception.[3]

Overdose

Tiagabine overdose can produce neurological symptoms such as lethargy, single or multiple seizures, status epilepticus, coma, confusion, agitation, tremors, dizziness, dystonias/abnormal posturing, and hallucinations, as well as respiratory depression, tachycardia, hypertension, and hypotension.[13] Overdose may be fatal especially if the victim presents with severe respiratory depression and/or unresponsiveness.[13]

Pharmacology

Tiagabine increases the level of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, by blocking the GABA transporter 1 (GAT-1), and hence is classified as a GABA reuptake inhibitor (GRI).[5][14] It has a half-life of 5-8 hours.[6]

History

Tiagabine was discovered at Novo Nordisk in Denmark in 1988 by a team of medicinal chemists and pharmacologists under the general direction of Claus Bræstrup.[15] The drug was co-developed with Abbott Laboratories, in a 40/60 cost sharing deal, with Abbott paying a premium for licensing the IP from the Danish company.

Abbott did initially embrace the drug enthusiastically after its U.S. launch in 1998, and provided further clinical studies with the goal of gaining FDA approval for monotherapy in epilepsy. However, the senior management at Abbott drew back after realizing that the original deal with Novo would limit the company's financial gain from a monotherapy approval. After a period of co-promotion, Cephalon licensed tiagabine from Abbott/Novo and now is the exclusive producer.

U.S. patents on tiagabine listed in the Orange Book expired in April 2016.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "TiaGABine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 562–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Gabitril (tiagabine hydrochloride) Tablets. U.S. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Cephalon, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- 1 2 Brodie, Martin J. (1995). "Tiagabine Pharmacology in Profile". Epilepsia. 36 (s6): S7–S9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb06015.x. ISSN 0013-9580. PMID 8595791. S2CID 27336198.

- 1 2 Rogawski, Michael A. (2020). "24. Antiseizure drugs". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 434. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ↑ "TiaGABine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ "Gabitril Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- 1 2 Stahl, S. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY. 2009. pp. 523-526

- 1 2 3 Leppik, Ilo E. (1995). "Tiagabine: The Safety Landscape". Epilepsia. 36 (s6): S10–S13. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb06009.x. ISSN 0013-9580. PMID 8595787. S2CID 24203401.

- ↑ M.J. Eadie; F. Vajda (6 December 2012). Antiepileptic Drugs: Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 459–. ISBN 978-3-642-60072-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ J. K. Aronson (2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Psychiatric Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 652–. ISBN 978-0-444-53266-4. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- 1 2 Spiller, Henry A.; Winter, Mark L.; Ryan, Mark; Krenzelok, Edward P.; Anderson, Debra L.; Thompson, Michael; Kumar, Suparna (2009). "Retrospective Evaluation of Tiagabine Overdose". Clinical Toxicology. 43 (7): 855–859. doi:10.1080/15563650500357529. ISSN 1556-3650. PMID 16440513. S2CID 25469390.

- ↑ Pollack MH, Roy-Byrne PP, Van Ameringen M, Snyder H, Brown C, Ondrasik J, Rickels K (November 2005). "The selective GABA reuptake inhibitor tiagabine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: results of a placebo-controlled study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (11): 1401–8. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n1109. PMID 16420077.

- ↑ Andersen KE, Braestrup C, Grønwald FC, Jørgensen AS, Nielsen EB, Sonnewald U, Sørensen PO, Suzdak PD, Knutsen LJ (1993). "The synthesis of novel GABA uptake inhibitors. 1. Elucidation of the structure-activity studies leading to the choice of (R)-1-[4,4-bis(3-methyl-2-thienyl)-3-butenyl]-3-piperidinecarboxylic acid (tiagabine) as an anticonvulsant drug candidate". J. Med. Chem. 36 (12): 1716–25. doi:10.1021/jm00064a005. PMID 8510100.

- ↑ Orange Book index page Archived 2018-11-01 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed March 22, 2016

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|