Meningococcal vaccine

Nimenrix - Meningococcal groups A, C, W-135 and Y conjugate vaccine | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Neisseria meningitidis |

| Type | Conjugate or polysaccharide |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Menactra, Menveo, Menomune, Others |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intramuscular (conjugate), Subcutaneous (polysaccharide) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Group B: Monograph ACYW: Monograph |

| US NLM | Meningococcal vaccine |

| MedlinePlus | a607020 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

Meningococcal vaccine refers to any of the vaccines used to prevent infection by Neisseria meningitidis.[1] Different versions are effective against some or all of the following types of meningococcus: A, B, C, W-135, and Y.[1][2] The vaccines are between 85 and 100% effective for at least two years.[1] They result in a decrease in meningitis and sepsis among populations where they are widely used.[3] They are given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.[1]

The World Health Organization recommends that countries with a moderate or high rate of disease or with frequent outbreaks should routinely vaccinate.[1][4] In countries with a low risk of disease, they recommend that high risk groups should be immunized.[1] In the African meningitis belt efforts to immunize all people between the ages of one and thirty with the meningococcal A conjugate vaccine are ongoing.[4] In Canada and the United States the vaccines effective against all four types of meningococcus are recommended routinely for teenagers and others who are at high risk.[1] Saudi Arabia requires vaccination with the quadrivalent vaccine for international travelers to Mecca for Hajj.[1][5]

Meningococcal vaccines are generally safe.[1] Some people develop pain and redness at the injection site.[1] Use in pregnancy appears to be safe.[4] Severe allergic reactions occur in less than one in a million doses.[1] After receiving the meningitis vaccine, teenagers should be observed for 15 minutes as they may feel light headed.[3]

The first meningococcal vaccine became available in the 1970s.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] Globally, its use has reduced the number of people contracting meningococcal meningitis.[3] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between US $3.23 and $10.77 per dose as of 2014.[8] In the United States it costs $100–200 for a course.[9]

Medical uses

Meningitis vaccines are used to protect against one or more of five of the six disease-causing types of Neisseria meningitidis (A, B, C, W and Y).[10]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established[11]

Types

Neisseria meningitidis has 12 clinically significant serogroups, classified according to the antigenic structure of their polysaccharide capsule. Six serogroups, A, B, C, Y, W-135, and X, are responsible for virtually all cases of the disease in humans.[12] A vaccine is available for 5 of them.[13] There is no vaccine that protects against group X.[14]

Quadrivalent (Serogroups A, C, W-135, and Y)

There are two quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines licensed and approved in the US; Menactra and Menveo.[3]

A polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV-4), Menomune, produced by Sanofi Pasteur.

Mencevax (GlaxoSmithKline) and NmVac4-A/C/Y/W-135 (JN-International Medical Corporation) are used worldwide, but have not been licensed in the United States.

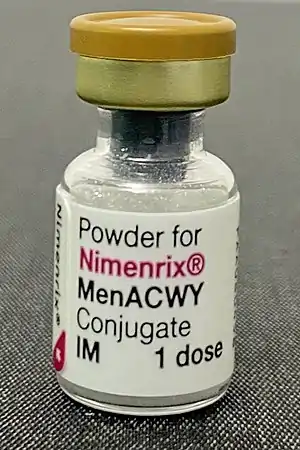

Nimenrix (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent conjugate vaccine against serogroups A, C, W-135, and Y, is available in the countries of the European Union[15] and some additional countries.

The first meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV-4), Menactra, was licensed in the U.S. in 2005 by Sanofi Pasteur; Menveo was licensed in 2010 by Novartis. Both MCV-4 vaccines have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for people 2 through 55 years of age. Menactra received FDA approval for use in children as young as 9 months in April 2011[16] while Menveo received FDA approval for use in children as young as 2 months in August 2013.[17] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has not made recommendations for or against its use in children less than 2 years.[18]

Meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV-4), Menomune, has been available since the 1970s. It may be used if MCV-4 is not available, and is the only meningococcal vaccine licensed for people older than 55. Information about who should receive the meningococcal vaccine is available from the CDC.[18]

Limitations

The duration of immunity mediated by Menomune (MPSV-4) is three years or less in children aged under five because it does not generate memory T cells.[19][20] Attempting to overcome this problem by repeated immunization results in a diminished, not increased, antibody response, so boosters are not recommended with this vaccine.[21][22] As with all polysaccharide vaccines, Menomune does not produce mucosal immunity, so people can still become colonised with virulent strains of meningococcus, and no herd immunity can develop.[23][24] For this reason, Menomune is suitable for travelers requiring short-term protection, but not for national public health prevention programs.

Menveo and Menactra contain the same antigens as Menomune, but the antigens are conjugated to a diphtheria toxoid polysaccharide–protein complex, resulting in anticipated enhanced duration of protection, increased immunity with booster vaccinations, and effective herd immunity.[25]

Endurance

A study published in March 2006, comparing the two kinds of vaccines found that 76% of subjects still had passive protection three years after receiving MCV-4 (63% protective compared with controls), but only 49% had passive protection after receiving MPSV-4 (31% protective compared with controls).[26] As of 2010, there remains limited evidence that any of the current conjugate vaccines offer continued protection beyond three years; studies are ongoing to determine the actual duration of immunity, and the subsequent requirement of booster vaccinations. The CDC offers recommendations regarding who they feel should get booster vaccinations.[27][28]

Bivalent (Serogroups C and Y)

On 14 June 2012, the FDA approved a combination vaccine against two types of meningococcal disease and Hib disease for infants and children 6 weeks to 18 months old. The vaccine, Menhibrix, prevents disease caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroups C and Y and Haemophilus influenzae type b. This was the first meningococcal vaccine that could be given to infants as young as six weeks old.[29]

Serogroup A

MenAfriVac, a meningitis A vaccine, has been developed through a program called the Meningitis Vaccine Project and has been shown to prevent outbreaks of group A meningitis, which is common in sub-Saharan Africa.[3]

Serogroup B

Vaccines against serotype B meningococcal disease have proved difficult to produce, and require a different approach from vaccines against other serotypes. Whereas effective polysaccharide vaccines have been produced against types A, C, W-135, and Y, the capsular polysaccharide on the type B bacterium is too similar to human neural adhesion molecules to be a useful target.[30]

A vaccine for serogroup B was developed in Cuba in response to a large outbreak of meningitis B during the 1980s. This vaccine was based on artificially produced outer membrane vesicles of the bacterium. The VA-MENGOC-BC vaccine proved safe and effective in randomized double-blind studies,[31][32][33] but it was granted a licence only for research purposes in the United States[34] as political differences limited cooperation between the two countries.[35]

Due to a similarly high prevalence of B-serotype meningitis in Norway between 1975 and 1985, Norwegian health authorities developed a vaccine specifically designed for Norwegian children and young adolescents. Clinical trials were discontinued after the vaccine was shown to cover only slightly more than 50% of all cases. Furthermore, lawsuits for damages were filed against the State of Norway by persons affected by serious adverse reactions. Information that the health authorities obtained during the vaccine development were subsequently passed on to Chiron (now GlaxoSmithKline), who developed a similar vaccine, MeNZB, for New Zealand.

A MenB vaccine was approved for use in Europe in January 2013. Following a positive recommendation from the European Union's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, Bexsero, produced by Novartis, received a licence from the European Commission.[36] However, deployment in individual EU member countries still depends on decisions by national governments. In July 2013, the United Kingdom's Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) issued an interim position statement recommending against adoption of Bexsero as part of a routine meningococcal B immunisation program, on the grounds of cost-effectiveness.[37] This decision was reverted in favor of Bexsero vaccination in March 2014.[38] In March 2015 the UK government announced that they had reached agreement with GlaxoSmithKline who had taken over Novartis' vaccines business, and that Bexsero would be introduced into the UK routine immunization schedule later in 2015.[39]

In November 2013, in response to an outbreak of B-serotype meningitis on the campus of Princeton University, the acting head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) meningitis and vaccine preventable diseases branch told NBC News that they had authorized emergency importation of Bexsero to stop the outbreak.[40] Bexsero was subsequently approved by the FDA in February 2015.[41] In October 2014, Trumenba, a serogroup B vaccine produced by Pfizer, was approved by the FDA.[2]

Serogroup X

The occurrence of serogroup X has been reported in North America, Europe, Australia, and West Africa.[42] There is no vaccine to protect against serogroup X N. meningitidis disease.[1]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) MenACWY vaccine

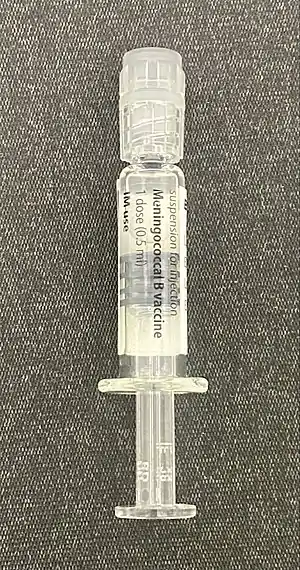

MenACWY vaccine MenB vaccine

MenB vaccine MenC and Hib vaccine

MenC and Hib vaccine

Side effects

Common side effects include pain and redness around the site of injection (up to 50% of recipients). A small percentage of people develop a mild fever. As with any medication, a small proportion of people develop a severe allergic reaction.[43] In 2016 Health Canada warned of an increased risk of anemia or hemolysis in people treated with eculizumab (Soliris). The highest risk was when individuals "received a dose of Soliris within 2 weeks after being vaccinated with Bexsero".[44]

Despite initial concerns about Guillain-Barré syndrome, subsequent studies in 2012 have shown no increased risk of GBS after meningococcal conjugate vaccination.[45]

Effectiveness

The widespread use of the quadrivalent meningitis vaccine in the US since 2005 has reduced the incidence of meningococcal disease in the US.[3] By June 2015, 220 million under 30 year olds received the meningitis A vaccine in 15 African countries, which reduced the number of cases of Meningococcal A disease by over 99%.[3] In countries which have implemented nation vaccination programmes, meningococcal A disease is almost eliminated.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 World Health Organization (November 2011). "Meningococcal vaccines : WHO position paper, November 2011". Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 86 (47): 521–540. hdl:10665/241846. PMID 22128384. Lay summary (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - 1 2 "First vaccine approved by FDA to prevent serogroup B Meningococcal disease". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 29 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Suryadevara, Manika (2021). "19. Meningococcus". In Domachowske, Joseph; Suryadevara, Manika (eds.). Vaccines: A Clinical Overview and Practical Guide. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 235–246. ISBN 978-3-030-58416-0. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Meningococcal A conjugate vaccine: updated guidance, February 2015" (PDF). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 90 (8): 57–62. 20 February 2015. hdl:10665/242320. PMID 25702330. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia: Hajj/Umrah Pilgrimage". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Pollard, Andrew J.; Snape, Matthew D.; Sadarangani, Manish (2021). "22. Meningoccal vaccines". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 249–260. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Vaccine, Meningococcal". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 315. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ McCarthy, Pumtiwitt C.; Sharyan, Abeer; Sheikhi Moghaddam, Laleh (25 February 2018). "Meningococcal Vaccines: Current Status and Emerging Strategies". Vaccines. 6 (1): 12. doi:10.3390/vaccines6010012. PMID 29495347. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ↑ "Meningitis". www.who.int. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ↑ Martinón-Torres, Federico; Banzhoff, Angelika; Azzari, Chiara; De Wals, Philippe; Marlow, Robin; Marshall, Helen; Pizza, Mariagrazia; Rappuoli, Rino; Bekkat-Berkani, Rafik (July 2021). "Recent advances in meningococcal B disease prevention: real-world evidence from 4CMenB vaccination". The Journal of Infection. 83 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.04.031. ISSN 1532-2742. PMID 33933528. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ↑ "Meningitis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ↑ "Nimenrix". European Medicines Agency. 24 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ "22 April 2011 Approval Letter - Menactra". Archived from the original on 28 April 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ "1 August 2013 Approval Letter - Menveo". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- 1 2 >"Meningococcal Vaccination - What You Should Know". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 July 2019. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ↑ Reingold AL, Broome CV, Hightower AW, et al. (1985). "Age-specific differences in duration of clinical protection after vaccination with meningococcal polysaccharide A vaccine". Lancet. 2 (8447): 114–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90224-7. PMID 2862316.

- ↑ Lepow ML, Goldschneider I, Gold R, Randolph M, Gotschlich EC (1977). "Persistence of antibody following immunization of children with groups A and C meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines". Pediatrics. 60 (5): 673–80. PMID 411104.

- ↑ Borrow R, Joseh H, Andrews N, et al. (2000). "Reduced antibody response to revaccination with meningococcal serogroup A polysaccharide vaccine in adults". Vaccine. 19 (9–10): 1129–32. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00317-0. PMID 11137248.

- ↑ MacLennan J, Obaro S, Deeks J, et al. (1999). "Immune response to revaccination with meningococcal A and C polysaccharides in Gambian children following repeated immunization during early childhood". Vaccine. 17 (23–24): 3086–93. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00139-5. PMID 10462244.

- ↑ Hassan-King MK, Wall RA, Greenwood BM (1988). "Meningococcal carriage, meningococcal disease and vaccination". J Infect. 16 (1): 55–9. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(88)96117-8. PMID 3130424.

- ↑ Moore PS, Harrison LH, Telzak EE, Ajello GW, Broome CV (1988). "Group A meningococcal carriage in travelers returning from Saudi Arabia". J Am Med Assoc. 260 (18): 2686–89. doi:10.1001/jama.260.18.2686. PMID 3184335.

- ↑ Deeks, E.D (October 2010). "Meningococcal quadrivalent (serogroups A, C, w135, and y) conjugate vaccine (Menveo): in adolescents and adults". BioDrugs. 4 (5): 72–6. PMID 21270745.

- ↑ Vu D, Welsch J, Zuno-Mitchell P, Dela Cruz J, Granoff D (2006). "Antibody persistence 3 years after immunization of adolescents with quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine". J Infect Dis. 193 (6): 821–8. doi:10.1086/500512. PMID 16479517.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (January 2011). "Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines --- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 60 (3): 72–6. PMID 21270745.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (September 2009). "Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for revaccination of persons at prolonged increased risk for meningococcal disease". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 58 (37): 1042–3. PMID 19779400.

- ↑ FDA approves new combination vaccine that protects children against two bacterial diseases Archived 2012-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, FDA Press Release, 14 June 2012

- ↑ Finne J et al. An IgG monoclonal antibody to group B meningococci cross-reacts with developmentally regulated polysialic acid units of glycoproteins in neural and extraneural tissues. Journal of Immunology 138(12), 4402–4407 (1987).

- ↑ Pérez O, Lastre M, Lapinet J, Bracho G, Díaz M, Zayas C, Taboada C, Sierra G (July 2001). "Immune Response Induction and New Effector Mechanisms Possibly Involved in Protection Conferred by the Cuban Anti-Meningococcal BC Vaccine". Infect Immun. 69 (7): 4502–8. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.7.4502-4508.2001. PMC 98525. PMID 11401992.

- ↑ Uli L, Castellanos-Serra L, Betancourt L, Domínguez F, Barberá R, Sotolongo F, Guillén G, Pajón Feyt R (June 2006). "Outer membrane vesicles of the VA-MENGOC-BC vaccine against serogroup B of Neisseria meningitidis: Analysis of protein components by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry". Proteomics. 6 (11): 3389–99. doi:10.1002/pmic.200500502. PMID 16673438.

- ↑ "Finlay Institute VA-MENGOC-BC Most frequent questions and answers". Archived from the original on 8 January 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ "World: Americas Cuba vaccine deal breaks embargo". BBC News Online. 29 July 1999. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ↑ NBC News Digital (12 November 2015). "Cuban scientist barred from receiving U.S. prize". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

A Cuban scientist who helped develop a low-cost synthetic vaccine that prevents meningitis and pneumonia in small children says he was offended the U.S. government denied his request to travel to the United States to receive an award.

- ↑ "First ever MenB vaccine available for use" Archived 2014-10-25 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Vaccine Group openminds blog article, 24 January 2013

- ↑ Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) (July 2013). "JCVI interim position statement on use of Bexsero® meningococcal B vaccine in the UK" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ John Porter (Novartis) (March 2014). "UK review of vaccines flawed, says Novartis' John Porter". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Meningitis B vaccine deal agreed - Jeremy Hunt". BBC News. 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ Aleccia, JoNell (15 November 2013). "Emergency meningitis vaccine will be imported to halt Ivy League outbreak". NBC News. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ "FDA approves a second vaccine to prevent serogroup B meningococcal disease" (Press release). United States Food and Drug Administration. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Clonal Groupings in Serogroup X Neisseria meningitidis. Archived 2009-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Vaccines: Vac-Gen/Side Effects". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ↑ Health Canada "Summary Safety Review - SOLIRIS (eculizumab) and BEXSERO - Assessing the Potential Risk of Hemolysis and Low Hemoglobin in Patients Treated with Soliris and Vaccinated with Bexsero". Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017. 16 September 2016

- ↑ Yih, Weiling Katherine; Weintraub, Eric; Kulldorff, Martin (1 December 2012). "No risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome found after meningococcal conjugate vaccination in two large cohort studies". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 21 (12): 1359–1360. doi:10.1002/pds.3353. ISSN 1099-1557. PMID 23225672.

Further reading

- Conterno LO, Silva Filho CR, Rüggeberg JU, Heath PT (2006). Conterno LO (ed.). "Conjugate vaccines for preventing meningococcal C meningitis and septicaemia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3 (3): CD001834. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001834.pub2. PMID 16855979.

- Patel M, Lee CK (2005). Patel M (ed.). "Polysaccharide vaccines for preventing serogroup A meningococcal meningitis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001093. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001093.pub2. PMID 15674874.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Meningococcal ACWY Vaccine Information Statement". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Meningococcal B Vaccine Information Statement". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Meningococcal (Groups A, C, Y and W-135) Polysaccharide Diphtheria Toxoid Conjugate Vaccine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Meningococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine, Groups A, C, Y and W-135 Combined". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Menveo". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 December 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Bexsero". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 October 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Trumenba". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 March 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Meningococcal Vaccines at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Meningococcal Vaccine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.