Sunburn

| Sunburn | |

|---|---|

| |

| A sunburned neck | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Initial: Red, hot, tender skin[1] Later: Skin peeling[1] |

| Complications | Dehydration, infection, skin cancer, skin aging, brown spots[1] |

| Usual onset | 2 to 6 hrs after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Sun exposure, tanning salons[1] |

| Risk factors | Lighter skin, living near the equator, high elevation, between 10 am and 2 pm, clear skies, reflection from snow[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dermatomyositis, erysipelas, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, Sezary syndrome, photodermatitis[2] |

| Prevention | Avoiding the sun around midday, sunscreen, sun protective clothing[1] |

| Treatment | Pain medication (NSAIDs), moisturizer[1][2] |

| Prognosis | Usually good[2] |

| Frequency | 34% per year (USA)[2] |

A sunburn is redness and swelling of the skin from overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation.[1] Onset is often 2 to 6 hours after exposure.[1] Other symptoms may include pain, warmth, and blistering.[1] After a few days skin peeling may occur.[1] Complications can include dehydration, infection, skin cancer, skin aging, and brown spots.[1]

It most commonly occurs due to Sun exposure, though can also result from other sources like tanning salons.[1] Those with lighter skin are more likely to sunburn.[1] Other risk factors include living near the equator, high elevation, between 10 am and 2 pm, clear skies, reflection from snow, and certain medications.[1][2] Medications involved may include doxycycline and HCTZ.[2] The underlying mechanism of injury involves DNA damage followed by programmed cell death.[2]

Preventive measures including avoiding the Sun around midday, sunscreen, and sun protective clothing.[1] Treatment involves pain medication such as NSAIDs and moisturizer.[1][2] A severe sunburn may required intravenous fluids such as Ringer's lactate.[2]

Sunburns affected about 34% of the population of the United States in 2015.[2] Young adults are most commonly affected.[2] Before 1820 it was believed that sunburns were due to heat.[3] Sunscreen was initially developed during World War Two.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Typically, there is initial redness, followed by varying degrees of pain, proportional in severity to both the duration and intensity of exposure.

Other symptoms can include blistering, swelling (edema), itching (pruritus), peeling skin, rash, nausea, fever, chills, and fainting (syncope). Also, a small amount of heat is given off from the burn, caused by the concentration of blood in the healing process, giving a warm feeling to the affected area. Sunburns may be classified as superficial, or partial thickness burns. Blistering is a sign of second degree sunburn.[4]

Variations

Minor sunburns typically cause nothing more than slight redness and tenderness to the affected areas. In more serious cases, blistering can occur. Extreme sunburns can be painful to the point of debilitation and may require hospital care.

.jpg.webp) Sunburn

Sunburn.jpg.webp) Sunburn

Sunburn.jpg.webp) Sunburn

Sunburn.jpg.webp) Sunburn

Sunburn Blisters from sunburn

Blisters from sunburn

Duration

Sunburn can occur in less than 15 minutes, and in seconds when exposed to non-shielded welding arcs or other sources of intense ultraviolet light. Nevertheless, the inflicted harm is often not immediately obvious.

After the exposure, skin may turn red in as little as 30 minutes but most often takes 2 to 6 hours. Pain is usually strongest 6 to 48 hours after exposure. The burn continues to develop for 1 to 3 days, occasionally followed by peeling skin in 3 to 8 days. Some peeling and itching may continue for several weeks.

Skin cancer

Ultraviolet radiation causes sunburns and increases the risk of three types of skin cancer: melanoma, basal-cell carcinoma and squamous-cell carcinoma.[5][6] [7] Of greatest concern is that the melanoma risk increases in a dose-dependent manner with the number of a person's lifetime cumulative episodes of sunburn.[8] It has been estimated that over 1/3 of melanomas in the United States and Australia could be prevented with regular sunscreen use.[9]

Causes

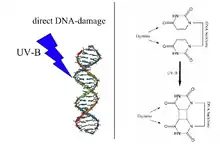

Sunburn is caused by UV radiation from the sun, but "sunburn" may result from artificial sources, such as tanning lamps, welding arcs, or ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. It is a reaction of the body to direct DNA damage from UVB light. This damage is mainly the formation of a thymine dimer. The damage is recognized by the body, which then triggers several defense mechanisms, including DNA repair to revert the damage, apoptosis and peeling to remove irreparably damaged skin cells, and increased melanin production to prevent future damage. Melanin readily absorbs UV wavelength light, acting as a photoprotectant. By preventing UV photons from disrupting chemical bonds, melanin inhibits both the direct alteration of DNA and the generation of free radicals, thus indirect DNA damage. However human melanocytes contain over 2,000 genomic sites that are highly sensitive to UV, and such sites can be up to 170-fold more sensitive to UV induction of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers than the average site[10] These sensitive sites often occur at biologically significant locations near genes.

Sunburn causes an inflammation process, including production of prostanoids and bradykinin. These chemical compounds increase sensitivity to heat by reducing the threshold of heat receptor (TRPV1) activation from 109 °F (43 °C) to 85 °F (29 °C).[11] The pain may be caused by overproduction of a protein called CXCL5, which activates nerve fibres.[12]

Skin type determines the ease of sunburn. In general, people with lighter skin tone and limited capacity to develop a tan after UV radiation exposure have a greater risk of sunburn. The Fitzpatrick's Skin phototypes classification describes the normal variations of skin responses to UV radiation. Persons with type I skin have the greatest capacity to sunburn and type VI have the least capacity to burn. However, all skin types can develop sunburn.[13]

Fitzpatrick's skin phototypes:

- Type 0: Albino

- Type I: Pale white skin, burns easily, does not tan

- Type II: White skin, burns easily, tans with difficulty

- Type III: White skin, may burn but tans easily

- Type IV: Light brown/olive skin, hardly burns, tans easily

- Type V: Brown skin, usually does not burn, tans easily

- Type VI: Black skin, very unlikely to burn, becomes darker with UV radiation exposure[14]

Age also affects how skin reacts to sun. Children younger than six and adults older than sixty are more sensitive to sunlight.[15]

There are certain genetic conditions, for example xeroderma pigmentosum, that increase a person's susceptibility to sunburn and subsequent skin cancers. These conditions involve defects in DNA repair mechanisms which in turn decreases the ability to repair DNA that has been damaged by UV radiation.[16]

Medications

The risk of a sunburn can be increased by pharmaceutical products that sensitize users to UV radiation. Certain antibiotics, oral contraceptives, antidepressants, acne medications, and tranquillizers have this effect.[17]

UV intensity

The UV Index indicates the risk of getting a sunburn at a given time and location. Contributing factors include:[15]

- The time of day. In most locations, the sun's rays are strongest between approximately 10am and 4pm daylight saving time.[18]

- Cloud cover. UV is partially blocked by clouds; but even on an overcast day, a significant percentage of the sun's damaging UV radiation can pass through clouds.[19][20]

- Proximity to reflective surfaces, such as water, sand, concrete, snow, and ice. All of these reflect the sun's rays and can cause sunburns.

- The season of the year. The position of the sun in late spring and early summer can cause a more-severe sunburn.

- Altitude. At a higher altitude it is easier to become burnt, because there is less of the earth's atmosphere to block the sunlight. UV exposure increases about 4% for every 1000 ft (305 m) gain in elevation.

- Proximity to the equator (latitude). Between the polar and tropical regions, the closer to the equator, the more direct sunlight passes through the atmosphere over the course of a year. For example, the southern United States gets fifty percent more sunlight than the northern United States.

Because of variations in the intensity of UV radiation passing through the atmosphere, the risk of sunburn increases with proximity to the tropic latitudes, located between 23.5° north and south latitude. All else being equal (e.g., cloud cover, ozone layer, terrain, etc.), over the course of a full year, each location within the tropic or polar regions receives approximately the same amount of UV radiation. In the temperate zones between 23.5° and 66.5°, UV radiation varies substantially by latitude and season. The higher the latitude, the lower the intensity of the UV rays. Intensity in the northern hemisphere is greatest during the months of May, June and July — and in the southern hemisphere, November, December and January. On a minute-by-minute basis, the amount of UV radiation is dependent on the angle of the sun. This is easily determined by the height ratio of any object to the size of its shadow (if the height is measured vertical to the earth's gravitational field, the projected shadow is ideally measured on a flat, level surface; furthermore, for objects wider than skulls or poles, the height and length are best measured relative to the same occluding edge). The greatest risk is at solar noon, when shadows are at their minimum and the sun's radiation passes most directly through the atmosphere. Regardless of one's latitude (assuming no other variables), equal shadow lengths mean equal amounts of UV radiation.

The skin and eyes are most sensitive to damage by UV at 265–275 nm wavelength, which is in the lower UVC band that is almost never encountered except from artificial sources like welding arcs. Most sunburn is caused by longer wavelengths, simply because those are more prevalent in sunlight at ground level.

Ozone depletion

In recent decades, the incidence and severity of sunburn have increased worldwide, partly because of chemical damage to the atmosphere's ozone layer. Between the 1970s and the 2000s, average stratospheric ozone decreased by approximately 4%, contributing an approximate 4% increase to the average UV intensity at the earth's surface. Ozone depletion and the seasonal "ozone hole" have led to much larger changes in some locations, especially in the southern hemisphere.[21]

Tanning

Suntans, which naturally develop in some individuals as a protective mechanism against the sun, are viewed by most in the Western world as desirable.[22] This has led to an overall increase in exposure to UV radiation from both the natural sun and tanning lamps. Suntans can provide a modest sun protection factor (SPF) of 3, meaning that tanned skin would tolerate up to three times the UV exposure as pale skin.[23]

Sunburns associated with indoor tanning can be severe.[24]

The World Health Organization, American Academy of Dermatology, and the Skin Cancer Foundation recommend avoiding artificial UV sources such as tanning beds, and do not recommend suntans as a form of sun protection.[25][26][27]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of sunburn includes other skin pathology induced by UV radiation including photoallergic reactions, phototoxic reactions to topical or systemic medications, and other dermatologic disorders that are aggravated by exposure to sunlight. Considerations for diagnosis include duration and intensity of UV exposure, use of topical or systemic medications, history of dermatologic disease, and nutritional status.

- Phototoxic reactions: Non-immunological response to sunlight interacting with certain drugs and chemicals in the skin which resembles an exaggerated sunburn. Common drugs that may cause a phototoxic reaction include amiodarone, dacarbazine, fluoroquinolones, 5-fluorouracil, furosemide, nalidixic acid, phenothiazines, psoralens, retinoids, sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, tetracyclines, thiazides, and vinblastine.[28]

- Photoallergic reactions: Uncommon immunological response to sunlight interacting with certain drugs and chemicals in the skin. When in excited state by UVR, these drugs and chemicals form free radicals that react to form functional antigens and induce a Type IV hypersensitivity reaction. These drugs include 6-methylcoumarin, aminobenzoic acid and esters, chlorpromazine, promethazine, diclofenac, sulfonamides, and sulfonylureas. Unlike phototoxic reactions which resemble exaggerated sunburns, photoallergic reactions can cause intense itching and can lead to thickening of the skin.[28]

- Phytophotodermatitis: UV radiation induces inflammation of the skin after contact with certain plants (including limes, celery, and meadow grass). Causes pain, redness, and blistering of the skin in the distribution of plant exposure.[13]

- Polymorphic light eruption: Recurrent abnormal reaction to UVR. It can present in various ways including pink-to-red bumps, blisters, plaques and urticaria.[13]

- Solar urticaria: UVR-induced wheals that occurs within minutes of exposure and fades within hours.[13]

- Other skin diseases exacerbated by sunlight: Several dermatologic conditions can increase in severity with exposure to UVR. These include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, acne, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea.[13]

Additionally, since sunburn is a type of radiation burn,[29][30] it can initially hide a severe exposure to radioactivity resulting in acute radiation syndrome or other radiation-induced illnesses, especially if the exposure occurred under sunny conditions. For instance, the difference between the erythema caused by sunburn and other radiation burns is not immediately obvious. Symptoms common to heat illness and the prodromic stage of acute radiation syndrome like nausea, vomiting, fever, weakness/fatigue, dizziness or seizure[31] can add to further diagnostic confusion.

Prevention

.jpg.webp)

The most effective way to prevent sunburn is to reduce the amount of UV radiation reaching the skin. The World Health Organization, American Academy of Dermatology, and Skin Cancer Foundation recommend the following measures to prevent excessive UV exposure and skin cancer:[32][33][34]

- Limiting sun exposure between the hours of 10am and 4pm, when UV rays are the strongest

- Seeking shade when UV rays are most intense

- Wearing sun-protective clothing including a wide brim hat, sunglasses, and tightly-woven, loose-fitting clothing

- Using sunscreen

- Avoiding tanning beds and artificial UV exposure

UV intensity

The strength of sunlight is published in many locations as a UV Index. Sunlight is generally strongest when the sun is close to the highest point in the sky. Due to time zones and daylight saving time, this is not necessarily at 12 noon, but often one to two hours later. Seeking shade including using umbrellas and canopies can reduce the amount of UV exposure, but does not block all UV rays. The WHO recommends following the shadow rule: "Watch your shadow – Short shadow, seek shade!"[32]

Sunscreen

Commercial preparations are available that block UV light, known as sunscreens or sunblocks. They have a sun protection factor (SPF) rating, based on the sunblock's ability to suppress sunburn: The higher the SPF rating, the lower the amount of direct DNA damage. The stated protection factors are correct only if 2 mg of sunscreen is applied per square cm of exposed skin. This translates into about 28 mL (1 oz) to cover the whole body of an adult male, which is much more than many people use in practice.[35] Sunscreens function as chemicals such as oxybenzone and dioxybenzone that absorb UV radiation (chemical sunscreens) or opaque materials such as zinc oxide or titanium oxide to physically block UV radiation (physical sunscreens).[36] Chemical and mineral sunscreens vary in the wavelengths of UV radiation blocked. Broad-spectrum sunscreens contain filters that protect against UVA radiation as well as UVB. Although UVA radiation does not primarily cause sunburn, it does contribute to skin aging and an increased risk of skin cancer.

Sunscreen is effective and thus recommended for preventing melanoma[37] and squamous cell carcinoma.[38] There is little evidence that it is effective in preventing basal cell carcinoma.[39] Typical use of sunscreen does not usually result in vitamin D deficiency, but extensive usage may.[40]

Recommendations

Research has shown that the best sunscreen protection is achieved by application 15 to 30 minutes before exposure, followed by one reapplication 15 to 30 minutes after exposure begins. Further reapplication is necessary only after activities such as swimming, sweating, and rubbing.[41] This varies based on the indications and protection shown on the label — from as little as 80 minutes in water to a few hours, depending on the product selected. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends the following criteria in selecting a sunscreen:[42]

- Broad spectrum: protects against both UVA and UVB rays

- SPF 30 or higher

- Water resistant: sunscreens are classified as water resistant based on time, either 40 minutes, 80 minutes, or not water resistant

Eyes

The eyes are also sensitive to sun exposure at about the same UV wavelengths as skin; snow blindness is essentially sunburn of the cornea. Wrap-around sunglasses or the use by spectacle-wearers of glasses that block UV light reduce the harmful radiation. UV light has been implicated in the development of age-related macular degeneration,[43] pterygium[44] and cataract.[45] Concentrated clusters of melanin, commonly known as freckles, are often found within the iris.

The tender skin of the eyelids can also become sunburned, and can be especially irritating.

Lips

The lips can become chapped (cheilitis) by sun exposure. Sunscreen on the lips does not have a pleasant taste and might be removed by saliva. Some lip balms (ChapSticks) have SPF ratings and contain sunscreens.

Feet

The skin of the feet is often tender and protected, so sudden prolonged exposure to UV radiation can be particularly painful and damaging to the top of the foot. Protective measures include sunscreen, socks, and swimwear or swimgear that covers the foot.

Diet

Dietary factors influence susceptibility to sunburn, recovery from sunburn, and risk of secondary complications from sunburn. Several dietary antioxidants, including essential vitamins, have been shown to have some effectiveness for protecting against sunburn and skin damage associated with ultraviolet radiation, in both human and animal studies. Supplementation with Vitamin C and Vitamin E was shown in one study to reduce the amount of sunburn after a controlled amount of UV exposure.[46] A review of scientific literature through 2007 found that beta carotene (Vitamin A) supplementation had a protective effect against sunburn, but that the effects were only evident in the long-term, with studies of supplementation for periods less than 10 weeks in duration failing to show any effects.[47] There is also evidence that common foods may have some protective ability against sunburn if taken for a period before the exposure.[48][49]

Children

Babies and children are particularly susceptible to UV damage which increases their risk of both melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers later in life. Children should not sunburn at any age and protective measures can ensure their future risk of skin cancer is reduced.[50]

- Infants 0–6 months: Children under 6mo generally have skin too sensitive for sunscreen and protective measures should focus on avoiding excessive UV exposure by using window mesh covers, wide brim hats, loose clothing that covers skin, and reducing UV exposure between the hours of 10am and 4pm.

- Infants 6–12 months: Sunscreen can safely be used on infants this age. It is recommended to apply a broad-spectrum, water-resistant SPF 30+ sunscreen to exposed areas as well as avoid excessive UV exposure by using wide-brim hats and protective clothing.

- Toddlers and Preschool-aged children: Apply a broad-spectrum, water-resistant SPF 30+ sunscreen to exposed areas, use wide-brim hats and sunglasses, avoid peak UV intensity hours of 10am-4pm and seek shade. Sun protective clothing with a SPF rating can also provide additional protection.

Artificial UV exposure

The WHO recommends that artificial UV exposure including tanning beds should be avoided as no safe dose has been established.[51] When one is exposed to any artificial source of occupational UV, special protective clothing (for example, welding helmets/shields) should be worn. Such sources can produce UVC, an extremely carcinogenic wavelength of UV which ordinarily is not present in normal sunlight, having been filtered out by the atmosphere.

Treatment

The primary measure of treatment is avoiding further exposure to the sun. The best treatment for most sunburns is time; most sunburns heal completely within a few weeks.

The American Academy of Dermatology recommends the following for the treatment of sunburn:[52]

- For pain relief, take cool baths or showers frequently.

- Use soothing moisturizers that contain aloe vera or soy.

- Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen or aspirin can help with pain.

- Keep hydrated and drink extra water.

- Do not pop blisters on a sunburn; let them heal on their own instead.

- Protect sunburned skin (see: Sun Protective Clothing and Sunscreen) with loose clothing when going outside to prevent further damage while not irritating the sunburn.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; such as ibuprofen or naproxen), and aspirin may decrease redness and pain.[53][54] Local anesthetics such as benzocaine, however, are contraindicated.[55] Schwellnus et al. state that topical steroids (such as hydrocortisone cream) do not help with sunburns,[54] although the American Academy of Dermatology says they can be used on especially sore areas.[55] While lidocaine cream (a local anesthetic) is often used as a sunburn treatment, there is little evidence for the effectiveness of such use.[56]

A home treatment that may help the discomfort is using cool and wet cloths on the sunburned areas.[54] Applying soothing lotions that contain aloe vera to the sunburn areas was supported by multiple studies,[57][58] though others have found aloe vera to have no effect.[54] Note that aloe vera has no ability to protect people from new or further sunburn.[59] Another home treatment is using a moisturizer that contains soy.[55]

A sunburn draws fluid to the skin’s surface and away from the rest of the body. Drinking extra water is recommended to help prevent dehydration.[55]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Sunburn | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Guerra, KC; Urban, K; Crane, JS (January 2021). "Sunburn". PMID 30521258.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Wang, Steven Q.; Lim, Henry W. (6 April 2016). Principles and Practice of Photoprotection. Springer. p. 339. ISBN 978-3-319-29382-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ↑ "How to treat sunburn | American Academy of Dermatology". www.aad.org. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer "Do sunscreens prevent skin cancer" Archived 26 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine Press release No. 132, 5 June 2000

- ↑ World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer "Solar and ultraviolet radiation" Archived 29 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 55, November 1997

- ↑ "Facts About Sunburn and Skin Cancer" Archived 2 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Skin Cancer Foundation

- ↑ Dennis LK, Vanbeek MJ, Beane Freeman LE, Smith BJ, Dawson DV, Coughlin JA (August 2008). "Sunburns and risk of cutaneous melanoma: does age matter? A comprehensive meta-analysis". Annals of Epidemiology. 18 (8): 614–27. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.04.006. PMC 2873840. PMID 18652979.

- ↑ Olsen CM, Wilson LF, Green AC, Biswas N, Loyalka J, Whiteman DC (January 2018). "How many melanomas might be prevented if more people applied sunscreen regularly?". The British Journal of Dermatology. 178 (1): 140–147. doi:10.1111/bjd.16079. PMID 29239489. S2CID 10914195. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ↑ Premi S, Han L, Mehta S, Knight J, Zhao D, Palmatier MA, Kornacker K, Brash DE. Genomic sites hypersensitive to ultraviolet radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Nov 26;116(48):24196-24205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907860116. Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID 31723047

- ↑ Linden DJ (2015). Touch: The Science of Hand, Heart and Mind. Viking. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ Dawes JM, Calvo M, Perkins JR, Paterson KJ, Kiesewetter H, Hobbs C, Kaan TK, Orengo C, Bennett DL, McMahon SB (July 2011). "CXCL5 mediates UVB irradiation-induced pain". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (90): 90ra60. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002193. PMC 3232447. PMID 21734176.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra A (2013). Fitzpatrick's color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-179302-5. OCLC 813301093.

- ↑ Wolff, K, ed. (2017). "PHOTOSENSITIVITY, PHOTO-INDUCED DISORDERS, AND DISORDERS BY IONIZING RADIATION". Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology (8th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Sunburn – Topic Overview". Healthwise. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ (1993). Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, Amemiya A (eds.). GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301571. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ "Avoiding Sun-Related Skin Damage". Fact-Sheets.com. 2004. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Tanning - Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation". Health Center for Devices and Radiological. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ↑ "Global Solar UV Index: A Practical Guide" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

Up to 80% of solar UV radiation can penetrate light cloud cover.

- ↑ "How UV Index Is Calculated". EPA. 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

Clear skies allow virtually 100% of UV to pass through, scattered clouds transmit 89%, broken clouds transmit 73%, and overcast skies transmit 31%.

- ↑ "Twenty Questions and Answers About the Ozone Layer" (PDF). Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2010. World Meteorological Organization. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ "Suntan". Healthwise. 27 March 2005. Retrieved 26 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

A UVB-induced tan provides minimal sun protection, equivalent to an SPF of about 3.

- ↑ Guy GP, Watson M, Haileyesus T, Annest JL (February 2015). "Indoor tanning-related injuries treated in a national sample of US hospital emergency departments". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (2): 309–11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6697. PMC 4593495. PMID 25506731.

- ↑ "Prevention - SkinCancer.org". www.skincancer.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ "Dangers of indoor tanning | American Academy of Dermatology". www.aad.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ↑ "WHO | Artificial tanning devices: public health interventions to manage sunbeds". WHO. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- 1 2 Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (8 April 2015). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (19th ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4. OCLC 893557976.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 "Sun protection". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "Prevention Guidelines - SkinCancer.org". www.skincancer.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "Prevent skin cancer | American Academy of Dermatology". www.aad.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ Faurschou A, Wulf HC (April 2007). "The relation between sun protection factor and amount of suncreen applied in vivo". The British Journal of Dermatology. 156 (4): 716–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07684.x. PMID 17493070. S2CID 22599824.

- ↑ Robertson DB (30 November 2017). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology: Dermatologic Pharmacology. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1259641152.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Kanavy HE, Gerstenblith MR (December 2011). "Ultraviolet radiation and melanoma". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 30 (4): 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.08.003. PMID 22123420.

- ↑ Burnett ME, Wang SQ (April 2011). "Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 27 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00557.x. PMID 21392107.

- ↑ Kütting B, Drexler H (December 2010). "UV-induced skin cancer at workplace and evidence-based prevention". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 83 (8): 843–54. doi:10.1007/s00420-010-0532-4. PMID 20414668. S2CID 40870536.

- ↑ Norval M, Wulf HC (October 2009). "Does chronic sunscreen use reduce vitamin D production to insufficient levels?". The British Journal of Dermatology. 161 (4): 732–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09332.x. PMID 19663879. S2CID 12276606.

- ↑ Diffey BL (December 2001). "When should sunscreen be reapplied?". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 45 (6): 882–5. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117385. PMID 11712033.

- ↑ "How to select a sunscreen | American Academy of Dermatology". www.aad.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ Glazer-Hockstein C, Dunaief JL (January 2006). "Could blue light-blocking lenses decrease the risk of age-related macular degeneration?". Retina. 26 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/00006982-200601000-00001. PMID 16395131.

- ↑ Solomon AS (June 2006). "Pterygium". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 90 (6): 665–6. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.091413. PMC 1860212. PMID 16714259.

- ↑ Neale RE, Purdie JL, Hirst LW, Green AC (November 2003). "Sun exposure as a risk factor for nuclear cataract". Epidemiology. 14 (6): 707–12. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000086881.84657.98. PMID 14569187. S2CID 40041207.

- ↑ Eberlein-König B, Placzek M, Przybilla B (January 1998). "Protective effect against sunburn of combined systemic ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and d-alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E)". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 38 (1): 45–8. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70537-7. PMID 9448204.

- ↑ Köpcke W, Krutmann J (2008). "Protection from sunburn with beta-Carotene--a meta-analysis". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 84 (2): 284–8. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00253.x. PMID 18086246.

- ↑ Stahl W, Sies H (September 2007). "Carotenoids and flavonoids contribute to nutritional protection against skin damage from sunlight". Molecular Biotechnology. 37 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1007/s12033-007-0051-z. PMID 17914160. S2CID 22417600.

- ↑ Schagen, S. K.; Zampeli, V. A.; Makrantonaki, E.; Zouboulis, C. C. (2012). "Discovering the link between nutrition and skin aging". Dermato-Endocrinology. 4 (3): 298–307. doi:10.4161/derm.22876. PMC 3583891. PMID 23467449.

- ↑ "Children - SkinCancer.org". www.skincancer.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "WHO | Artificial tanning devices: public health interventions to manage sunbeds". WHO. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "How to treat sunburn | American Academy of Dermatology". www.aad.org. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "Sunburn – Home Treatment". Healthwise. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Schwellnus MP (2008). The Olympic textbook of medicine in sport. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-4443-0064-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "How to treat sunburn". American Academy of Dermatology. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ↑ Arndt KA, Hsu JT (2007). Manual of Dermatologic Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7817-6058-4. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ↑ Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew C (September 2007). "The efficacy of aloe vera used for burn wound healing: a systematic review". Burns. 33 (6): 713–8. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.384. PMID 17499928.

- ↑ Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Shi, M.; Fan, P.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N. (2018). "Aloin Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis by Inhibiting the Activation of NF-κB". Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 23 (3): 517. doi:10.3390/molecules23030517. PMC 6017010. PMID 29495390.

- ↑ Feily A, Namazi MR (February 2009). "Aloe vera in dermatology: a brief review". Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 144 (1): 85–91. PMID 19218914.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Sunburn at Curlie