Áras an Uachtaráin

Áras an Uachtaráin (Irish pronunciation: [ˈaːɾˠəsˠ ənˠ ˈuəxt̪ˠəɾˠaːnʲ]; "Residence of the President"), formerly the Viceregal Lodge, is the official residence and principal workplace of the President of Ireland. It is located off Chesterfield Avenue in the Phoenix Park in Dublin. The building design was credited to amateur architect Nathaniel Clements but more likely guided by professionals (John Wood of Bath, Sir Edward Lovett Pearce and Richard Cassels) and completed around 1751 to 1757.[2]

| Áras an Uachtaráin | |

|---|---|

North rear facade | |

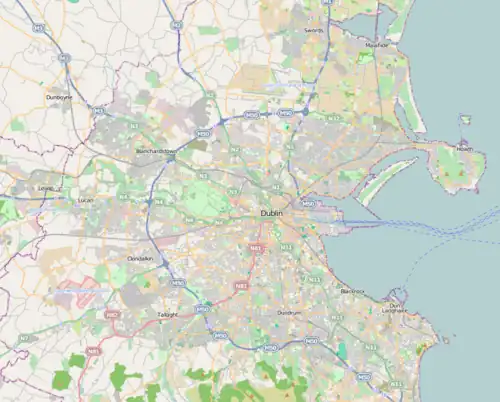

Áras an Uachtaráin Location within Dublin | |

| Former names | Viceregal Lodge |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Classification | Private |

| Location | Phoenix Park |

| Town or city | Dublin |

| Country | Ireland |

| Coordinates | 53.359676°N 6.31745°W |

| Current tenants | President of Ireland |

| Completed | 1751[1] |

| Renovated | 1840s, 1849, 1852, 1908, 1911 |

| Owner | Government of Ireland |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 92 |

| Website | |

| president | |

Origins

The original house was designed by park ranger and amateur architect Nathaniel Clements in the mid-18th century. It was bought by the Crown in the 1780s to become the summer residence of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the British viceroy in the Kingdom of Ireland. His official residence was in the Viceregal Apartments in Dublin Castle. The house in the park later became the Viceregal Lodge, the "out of season" residence of the Lord Lieutenant (also known as the Viceroy), where he lived for most of the year from the 1820s onwards. During the Social Season (January to Saint Patrick's Day in March), he lived in state in Dublin Castle.

Phoenix Park once contained three official state residences. The Viceregal Lodge, the Chief Secretary's Lodge and the Under Secretary's Lodge. The Chief Secretary's Lodge, now called Deerfield, is the official residence of the United States Ambassador to Ireland. The Under Secretary's Lodge, now demolished, served for many years as the Apostolic Nunciature.

Some historians have claimed that the garden front portico of Áras an Uachtaráin (which can be seen by the public from the main road through the Phoenix Park) was used as a model by Irish architect James Hoban, who designed the White House in Washington, D.C. However, the porticoes were not part of Hoban's original design and were, in fact, added to the White House at a later date by Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

Phoenix Park Murders

In 1882, its grounds were the location of the Phoenix Park Murders. The Chief Secretary for Ireland (the British Cabinet minister with responsibility for Irish affairs), Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his undersecretary, Thomas Henry Burke, were stabbed to death with surgical knives while walking back to the residence from Dublin Castle. A small insurgent group called the Irish National Invincibles was responsible. The 5th Earl Spencer, the then Lord Lieutenant, heard the victims' screams from a window in the ground floor drawing room.

Residence of the Governor-General

In 1911, the house underwent a large extension for the visit of King George V and Queen Mary. With the creation of the Irish Free State in December 1922, the office of Lord Lieutenant was abolished. The new state intended to place the new representative of the Crown, Governor-General Tim Healy, in a new, smaller residence, but because of death threats from the anti-treaty IRA, he was installed in the Viceregal Lodge temporarily. The building was at the time nicknamed "Uncle Tim's Cabin" after him, in imitation of the famous US novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by the US author Harriet Beecher Stowe.[3] It remained the official residence of the Governor-General of the Irish Free State until 1932, when the new Governor-General, Domhnall Ua Buachalla, was installed in a specially hired private mansion in the southside of Dublin.

Residence of the President

The house was left empty until 1938, when the first President of Ireland, Douglas Hyde, lived there temporarily while plans were made to build a new presidential palace on the grounds. The outbreak of the Second World War saved the building, which had been renamed Áras an Uachtaráin (meaning house or residence of the president in Irish), from demolition, as plans for its demolition and the design of a new residence were put on hold.[4] By 1945 it had become too closely identified with the presidency of Ireland to be demolished, though its poor condition meant that extensive demolition and rebuilding of parts of the building were necessary, notably the kitchens, servants' quarters and chapel. Since then, further restoration work has been carried out from time to time.

President Hyde lived in the residential quarters on the first floor of the main building. Later presidents moved to the new residential wing attached to the main house that had been built on for the visit of King George V in 1911. However, in 1990 Mary Robinson moved back to the older main building. Her successor, Mary McAleese, lived in the 1911 wing.

Though Áras an Uachtaráin is possibly not as palatial as other European royal and presidential palaces, with only a handful of staterooms (the state drawing room, large and small dining rooms, the President's Office and Library, a large ballroom and a presidential corridor lined with the busts of past presidents (Francini Corridor), and some fine eighteenth and nineteenth century bedrooms above, all in the main building), it is a relatively comfortable state residence.

All taoisigh as well as government ministers receive their seal of office from the president at Áras an Uachtaráin as do judges, the attorney general, the comptroller and auditor general, and senior commissioned officers of the Defence Forces. It is also the venue for the meetings of the Presidential Commission and the Council of State.

Áras an Uachtaráin also houses the headquarters of the Garda Mounted Unit.

The Office of Public Works completely furnishes the private quarters of Áras an Uachtaráin for the presidential family.[5]

Visitors

Various visiting British monarchs stayed at the Viceregal Lodge while Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, notably Queen Victoria and King George V. American presidents hosted there include John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton,Barack Obama, and Joe Biden.[6] Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has also visited. Other famous visitors to Áras an Uachtaráin have been Nelson Mandela, Aung Sang Suu Kyi, Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace of Monaco; King Baudouin of Belgium; King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía of Spain; Pope John Paul II; Prince Charles and Prince Philip; Indian prime-ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Narendra Modi; and Pope Francis.

On 17 May 2011, Queen Elizabeth II became the first British monarch to visit the residence in 100 years, on the occasion of her state visit to Ireland.[7] She was welcomed by President Mary McAleese, inspected a guard of honour, signed the visitors book and planted an Irish oak sapling.

Guests do not normally stay at Áras an Uachtaráin. Although it has 92 rooms,[8] many of these are used for storage of presidential files, for household staff and official staff, including military aides-de-camp, a secretary to the president, and a press office. Foreign dignitaries usually stay at Farmleigh, the State reception house, located close to Áras an Uachtaráin in Castleknock.

On 1 May 2004, during Ireland's six-month presidency of the European Union, Áras an Uachtaráin was the Venue for the European Day of Welcomes (Accession Day) in which ten new members joined the EU. All 25 heads of government attended the flag-raising ceremony in the gardens of the building. A large security operation involving the Garda Síochána and the Irish Defence Forces closed off Áras an Uachtaráin and the Phoenix Park.

Like most OPW buildings, Áras an Uachtaráin is open for free guided tours every Saturday.

References

- "Outline History of Áras an Uachtaráin". Áras an Uachtaráin. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- History of Áras an Uachtaráin, p8

- Ayto, John & Crofton, Ian (2005). Brewer's Britain and Ireland. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 873. Consulted 5 April 2014.

- "7 things you probably didn't know about Áras an Uachtaráin". RTÉ News. 23 October 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Mammoth task of moving out done in military style". Irish Independent. 10 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "US President rings Peace Bell at Áras an Uachtaráin". 23 April 2023.

- "Queen lays wreath on Republic of Ireland state visit". BBC News. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- "Áras an Uachtaráin". IrishTourism.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.