Saint-Augustin, Paris

The Église Saint-Augustin de Paris (Church of St. Augustine) is a Roman Catholic church located at 46 boulevard Malesherbes in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. The church was built between 1860 and 1871 by the Paris city chief architect Victor Baltard. It was the first church in Paris to combine a cast-iron frame, fully visible, with stone construction. It was designed to provide a prominent landmark at the junction of two new boulevards built during Haussmann's renovation of Paris under Napoleon III.[2]

[3] The closest métro station is Saint-Augustin ![]()

![]()

| Église Saint-Augustin de Paris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | 8th arrondissement of Paris |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Website | saintaugustin.net |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | |

| Designated | 1993 |

| Architect(s) | Victor Baltard |

| Style | Eclectic; Romano-Byzantine |

| Groundbreaking | 1860 |

| Completed | 1868 |

In 1886, Saint-Augustin was the site of the conversion of Charles de Foucauld, who was canonised as a Saint by Pope Francis on 15 May 2022. The church includes a chapel dedicated to Foucauld, in which is preserved the confessional where he returned to the Catholic Church.[4]

History

In the 1850s and 1860s Napoleon III carried out a massive reconstruction of the center of Paris, which was carried out by Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Wide boulevards were built to cut through the overcrowded medieval city, with monumental new buildings at the meeting points of the new boulevards. Saint-Augustin was intended to be the anchor of Boulevard Malesherbes, balancing The Church of La Madeleine at the other end. It was also designed to be visible from the Arc de Triomphe down the avenue de Friedland. The size and design of the church was inspired by Saint Paul's and other great churches of London, where Napoleon III had lived in exile before becoming President of France and then Emperor.[5]

The church was designed by Haussmann's fellow Protestant, architect Victor Baltard, who from 1849 onwards was Chief Architect of the City of Paris. He was responsible for the restoration of several Paris churches damaged in the French Revolution, including Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, Saint-Séverin, Paris, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés. In the 1850s he designed his most famous work, Les Halles markets, also using an iron structure. They were demolished in the 1970s and replaced by an underground shopping mall.[6]

The chosen site was trapezoid-shaped lot at the intersection of four streets, which meant that the back of the church was wider than the front. The length of the boulevard, the small site the need to make the church visible from far away, called for a dome of 61 metres (200 feet) which covered virtually the entire church.[7] The key innovation of Baltard was the use of cast iron for the structure of the church which permitted Baltard to greatly reduce the thickness of the walls, and to eliminate the need for heavy buttresses outside.[8]

By the end of the 20th century, after the period of modernism, the church design was considered by some holding modernist views to be out of fashion, although this view has largely been superseded in favour of conservation. As late as 1995, one critic described the church as "an eyesore: ridiculously sited, without proportion, crushed beneath an outsized dome".[9][10] Despite this, it is still considered a masterpiece of architecture of the Second Empire and is duly given the honour of Monument Historique by the French State[11]

Exterior

The church was built between 1860 and 1871 in an eclectic style combining Tuscan Gothic, Romanesque and Byzantine elements. The church is very large: one hundred meters long and eighty meters high to the lantern of the dome, which has a diameter of 25 meters. Because of the boulevards that converge at the site, it also has an unusual shape, a trapezoid, with the front much narrower than the rear. The dome occupies almost the entire facade.

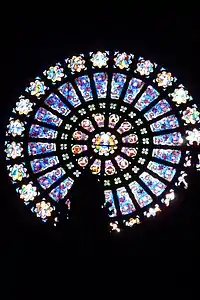

Saint-Augustin's facade features a frieze by sculptor François Jouffroy depicting Jesus and the twelve apostles above the four evangelists. The rose window was designed by Prosper Lafaye (1806-1833). It has the unusual feature of being reinforced with an armature of cast iron. The dome is surrounded by four towers which serve as buttresses.[12]

The facade

The facade.jpg.webp) The apse or rear of the church, surrounded by chapels

The apse or rear of the church, surrounded by chapels

Interior: the nave and choir

The most striking feature of the interior is the great open space, made possible by the cast-iron frame and roof. The frame, which is fully visible, serves as well as a decorative element; the cast-iron columns line the walls, and are painted and decorated with gilding and with polychrome angels, created by Louis Schroeder (1828-1898).[13]

The choir is the portion of the church reserved for the clergy in the centre of the church, and is raised. Over the altar is a ciborium or baldaquin, an open walled domed structure made of gilded cast iron, in the Renaissance style. A modern, moveable altar is placed in the centre of the choir, obstructing the view of the main high altar, in order to facilitate mass versus populum , and may be removed when mass is celebrated ad orientem, whether in the reformed rite or traditional Catholic rite.

.jpg.webp) The nave, choir and the ciborium over the altar with the original high altar partially obstructed by the modern timber altar

The nave, choir and the ciborium over the altar with the original high altar partially obstructed by the modern timber altar.jpg.webp) The interior of the dome, eighty meters high, showing its iron structure

The interior of the dome, eighty meters high, showing its iron structure The Ciborium or baldequin over the main altar

The Ciborium or baldequin over the main altar

Chapels

A series of chapels, filled with art, surround the nave and choir. On the right side of the nave is a chapel dedicated to the soldier, geographer and priest Charles de Foucauld, who was converted to Christianity in the church in 1886. It displays documents related to his life. He was beatified 2005 and declared a saint in 2022.

The largest chapel is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and by tradition is located in the apse at the east end of the church. [14]

Three chapels are placed around the choir, and are decoration with lavish materials; they are entered through archways with rose-colored marble columns and arches, and altars decorated with mosaics.

The Chapel of the Virgin

The Chapel of the Virgin Chapel of the Sacred Heart

Chapel of the Sacred Heart The Chapel of Saint Joseph

The Chapel of Saint Joseph

The austere Foucauld Chapel, dedicated to Saint Charles de Foucauld, who was cannoized in 2005.

The austere Foucauld Chapel, dedicated to Saint Charles de Foucauld, who was cannoized in 2005.

Art and Decoration

The church is lavishly decorated with art. The stained glass windows depict bishops and martyrs of the first centuries and the cast-iron columns are decorated with polychrome angels. A statue of Joan of Arc, by Paul Dubois, was erected in the church in 1896. The church features paintings by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin, Émile Signol, Alexandre-Dominique Denuelle and sculpture by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse and Henri Chapu.[1] The large oval paintings of Saints and angels on the upper walls were made by William Bouguereau (1825-1925}. He simplified and enlarged the figures because of their height on the walls and the dim light, and often placed them against a background of a blue sky.

The frieze depicting Christ and the Twelve Apostles over the west portal

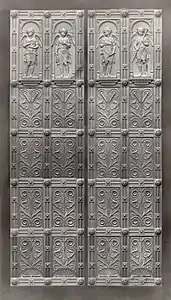

The frieze depicting Christ and the Twelve Apostles over the west portal Portal doors by Charles Marville (1850-70)

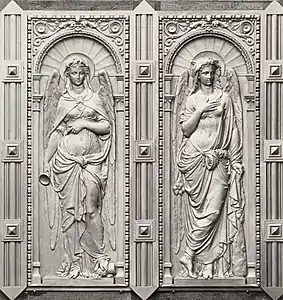

Portal doors by Charles Marville (1850-70) Sculpture by Charles Marville (c. 1853-70)

Sculpture by Charles Marville (c. 1853-70)

Saint Matthew on the facade

Saint Matthew on the facade Rose window exterior

Rose window exterior A sculpted cast iron post from the interior

A sculpted cast iron post from the interior

_%C3%89glise_Saint-Augustin_-_Ext%C3%A9rieur_-_Fa%C3%A7ade_principale_-_18.jpg.webp) Decoration on the facade: "Faith", painted by Paul Balze

Decoration on the facade: "Faith", painted by Paul Balze_%C3%89glise_Saint-Augustin_-_Ext%C3%A9rieur_-_Fa%C3%A7ade_principale_-_17.jpg.webp) Facade: "Hope" by Paul Balze

Facade: "Hope" by Paul Balze

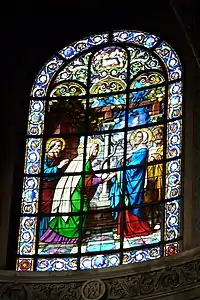

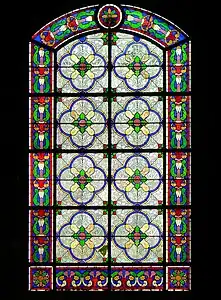

Stained glass

Unlike the custom in other 19th-century churches, the architect Baltard did not install white glass to bring more light into the nave. On the two lower levels of the nave, he employed windows with geometric figures. On top level, he used images of saints and martyrs, The stained glass of the windows on the dome over the choir are coloured with grisaille, heightened with jaune d'argent. This accounts for the rather dim light in the nave.[15]

The stained glass portraits of saints surrounding the dome are examples of monochrome grisaille windows, highlighted with gilded designs The chapels around the nave and the choir feature windows devoted to saints and apostles, noting the names of the donors at the bottom.[16]

the rose window, made with an iron framework

the rose window, made with an iron framework "An Angel" (detail - click to enlarge)

"An Angel" (detail - click to enlarge) "The Visitation" (apse)

"The Visitation" (apse)

"Descent from the cross" (Apse)

"Descent from the cross" (Apse) "Saint Vincent de Paul, a Grisaille window on the drum of dome

"Saint Vincent de Paul, a Grisaille window on the drum of dome Geometric window designs (nave)

Geometric window designs (nave) Window detail (nave}

Window detail (nave}

Organs

The organ is celebrated in the world of organ building. The church's main organ was built by Charles Spackman Barker, famous in the organ design world for inventing « machine Barker » which revolutionised the means of transmission from the keyboard to the organ pipes. It was constructed in 1867-1868, and dedicated on June 17, 1868. The same organ was also one of the first to employ electricity. It was removed for restoration by Cavaillé-Coll (1899), Beuchet-Debierre (1961) and Dargassies (1987). It features 54 stops with three 54-key manual keyboards and pedalboards.[17]

The church has a smaller organ located just over the choir. The choir organ was built by Cavaillé-Coll-Mutin in 1899, rebuilt by Danion-Gonzalez in 1973,and(1983) It has two keyboards with 61 notes, a pedalier with 32 notes, electric transmission, and 30 pipes, 21 working.[17]

.jpg.webp) The grand organ over the west entrance of the nave

The grand organ over the west entrance of the nave The grand organ and the rose window

The grand organ and the rose window The choir organ

The choir organ

The Church and its setting

The church was designed to be a highly-visible landmark at the meeting of two boulevards, and to be seen from the top of the Arc de Triumphe.

The church in the 1890s

The church in the 1890s From the Arc de Triomphe

From the Arc de Triomphe

References

- Base Mérimée: Eglise Saint-Augustin, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- Dumoulin. "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 141

- "Saint Augustin Church". Napoleon.org.

- "COMMISSION DIOCÉSAINE D'ART SACRÉ DE PARIS".

- Dumoulin. "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 141

- Church history and art (in French)

- Dumoulin. "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 141

- Jordan, p. 489.

- Jordan, p. 195.

- Jordan, p. 243.

- "Eglise Saint-Augustin".

- Dumoulin. "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 141

- Dumoulin. "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 141

- Dumoulin. "Églises de Paris" (2010), p. 141

- Site on church history and art (in French)

- Site on church history and art (in French)

- "Saint Augustin". The Organs of Paris.

Sources

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1 (in French)

- Jordan, David P. (1995). Transforming Paris: The Life and Labors of Baron Haussman. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439106013.

External links

- Official church website

- Lartnouveau.com article (in French)

- patrimoine-histoire.fr (Site on history, architecture, art and decoration of church (in French)