Flag of Hong Kong

The flag of Hong Kong, officially the regional flag of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China, depicts a white stylised five-petal Hong Kong orchid tree (Bauhinia blakeana) flower in the centre of a Chinese red field. Its original design was unveiled on 4 April 1990 at the Third Session of the Seventh National People's Congress.[1][2] The current design was approved on 10 August 1996 at the Fourth Plenum of the Preparatory Committee of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.[3] The precise use of the flag is regulated by laws passed by the 58th executive meeting of the State Council held in Beijing.[4] The design of the flag is enshrined in Hong Kong's Basic Law, the territory's constitutional document,[5] and regulations regarding the use, prohibition of use, desecration, and manufacture of the flag are stated in the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance.[6] The flag of Hong Kong was officially adopted and hoisted on 1 July 1997, during the handover ceremony marking the transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom back to China.[7]

| |

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil and state ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | Approved on 4 April 1990 by the National People's Congress; first flown on 1 July 1997 |

| Design | A stylised, white, five-petal Bauhinia blakeana flower in the centre of a red field |

| Designed by | Tao Ho |

| Regional flag of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 中華人民共和國香港特別行政區區旗 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华人民共和国香港特别行政区区旗 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Current design

Symbolism

.svg.png.webp)

The design of the flag comes with cultural, political, and regional meanings. The colour itself is significant; red is a festive colour for the Chinese people, used to convey a sense of celebration and nationalism.[8] Moreover, the red colour is identical to that used in the national PRC flag,[9] chosen to signify the link re-established between post-colonial Hong Kong and Mainland China. The position of red and white on the flag symbolises the "one country, two systems" political principle applied to the region. The stylised rendering of the Bauhinia blakeana flower, a flower discovered in Hong Kong, is meant to serve as a harmonising symbol for this dichotomy.[8] The five stars of the Chinese national flag are replicated on the petals of the flower. The Chinese name of Bauhinia × blakeana is most commonly rendered as "洋紫荊", but is often shortened to 紫荊 / 紫荆 in official uses since "洋" (yáng) means "foreign" in Chinese, notwithstanding 紫荊 / 紫荆 refers to another genus called Cercis. A sculpture of the plant has been erected in Golden Bauhinia Square in Hong Kong.

Before the adoption of the flag, the Chairman of the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee explained the significance of the flag's design to the National People's Congress:

The regional flag carries a design of five bauhinia petals, each with a star in the middle, on a red background. The red flag represents the motherland and the bauhinia represents Hong Kong. The design implies that Hong Kong is an inalienable part of China and prospers in the embrace of the motherland. The five stars on the flower symbolise the fact that all Hong Kong compatriots love their motherland, while the red and white colours embody the principle of "one country, two systems".[10]

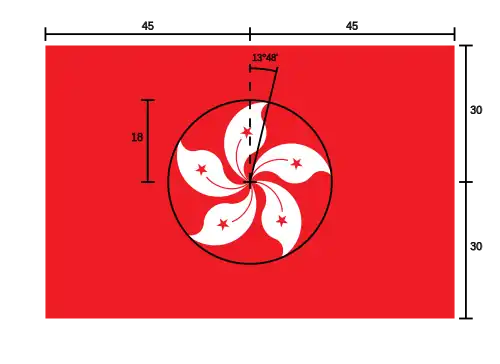

Construction

The Hong Kong government has specified sizes, colours, and manufacturing parameters in which the flag is to be made. The ratio of its length to breadth is 3:2. In its centre is a five-petal stylised rendering of a white Bauhinia blakeana flower. If a circle circumscribes the flower, it should have a diameter 0.6 times the entire height of the flag. The petals are uniformly spread around the centre point of the flag, radiating outward and pointing in a clockwise direction. Each of the flower's petals bears a five-pointed red star with a red trace, suggestive of a flower stamen. The heading that is used to allow a flag to be slid or raised onto a pole is white.[9]

A slightly different geometrical description of the flag is specified in the mandatory National Standard "GB 16689-2004: Regional flag of Hong Kong special administrative region".[note 1]

Size specifications

This table lists all the official sizes for the flag. Sizes deviating from this list are considered non-standard. If a flag is not of official size, it must be a scaled-down or scaled-up version of one of the official sizes.[9]

| Size | Length and width in centimetres |

|---|---|

| 1 | 288 × 192 |

| 2 | 240 × 160 |

| 3 | 192 × 128 |

| 4 | 144 × 96 |

| 5 | 96 × 64 |

| Car flag | 30 × 20 |

| Flag for signing ceremonies | 21 × 14 |

| Desktop flag | 15 × 10 |

Colour specifications

The Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance stipulates that "The regional flag is in red, the chrominance value of which is identical with that of the national flag of the People's Republic of China."

Manufacture regulations

The Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance stipulates that the Hong Kong flag must be manufactured according to specifications laid out in the ordinance. If flags are not produced in design according to the ordinance, the Secretary for Justice may petition the District Court for an injunction to prohibit the person or company from manufacturing the flags. If the District Court agrees that the flags are not in compliance, it may issue an injunction and order that the flags and the materials that were used to make the flags to be seized by the government.[11]

Protocol

The Hong Kong flag is flown daily from the chief executive's official residence, Government House, the Hong Kong International Airport, and at all border crossings and points of entry into Hong Kong.[12] At major government offices and buildings, such as the Office of the Chief Executive, the Executive Council, the Court of Final Appeal, the High Court, the Legislative Council, and the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Offices overseas, the flag is displayed during days when these offices are working. Other government offices and buildings, such as hospitals, schools, departmental headquarters, sports grounds, and cultural venues should fly the flag on occasions such as the National Day of the PRC (1 October), the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Establishment Day (1 July), and New Year's Day.[12] The flag should be raised at 8:00 a.m. and lowered at 6:00 p.m. The raising and lowering of the flag should be done slowly; it must reach the peak of the flag staff when it is raised, and it may not touch the ground when it is lowered. The flag may not be raised in severe weather conditions.[13] A Hong Kong flag that is either damaged, defaced, faded or substandard must not be displayed or used.[14]

Display

Whenever the PRC national flag is flown together with the regional Hong Kong flag, the national flag must be flown at the centre, above the regional flag, or otherwise in a more prominent position than that of the regional flag. The regional flag must be smaller in size than the national flag, and it must be displayed to the left of the national flag. When the flags are displayed inside a building, the left and right sides of a person looking at the flags, and with his or her back toward the wall, are used as reference points for the left and right sides of a flag. When the flags are displayed outside a building, the left and right sides of a person standing in front of the building and looking towards the front entrance are used as reference points for the left and right sides of a flag. The national flag should be raised before the regional flag is raised, and it should be lowered after the regional flag is lowered.[13]

An exception to this rule occurs during medal presentation ceremonies at multi-sport events such as the Olympics and Asian Games. As Hong Kong competes separately from mainland China, should an athlete from Hong Kong win the gold medal, and an athlete from mainland China win the silver and/or bronze medal(s) in the same event, the regional flag of Hong Kong would be raised in the centre above the national flag(s) during the medal presentation ceremony.

Protocol examples. Note how the national flag is bigger than the regional flag in both examples.

Protocol examples. Note how the national flag is bigger than the regional flag in both examples. The flag of Hong Kong flying beside the national PRC flag

The flag of Hong Kong flying beside the national PRC flag The Hong Kong flag and the national PRC flag flown side by side at the patio of the former Legislative Council Building

The Hong Kong flag and the national PRC flag flown side by side at the patio of the former Legislative Council Building

Half-mast

The Hong Kong flag must be lowered to half-mast as a token of mourning when any of the following people die:[14]

- President of the People's Republic of China

- Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress

- Premier of the State Council

- Chairman of the Central Military Commission

- Chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference

- Persons who have made outstanding contributions to the People's Republic of China as the Central People's Government advises the Chief Executive.

- Persons who have made outstanding contributions to world peace or the cause of human progress as the Central People's Government advises the Chief Executive.

- Persons whom the Chief Executive considers to have made outstanding contributions to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region or for whom they consider it appropriate to fly the flag at half-mast.

The flag may also be flown at half-mast when the Central People's Government advises the Chief Executive to do so, or when the Chief Executive considers it appropriate to do so, on occurrences of unfortunate events causing especially serious casualties, or when serious natural calamities have caused heavy casualties.[14] When raising a flag to be flown at half-mast, it should first be raised to the top of the pole and then lowered to a point where the distance between the top of the flag and the top of the pole is one third of the length of the pole. When lowering the flag from half-mast, it should first be raised to the peak of the pole before it is lowered.[13]

Prohibition of use and desecration

The Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance states what manner of use of the Hong Kong flag is prohibited and that desecration of the flag is prohibited; it also states that it is a punishable offence for a person to use the flag in a prohibited manner or desecrate the flag. According to the ordinance, a flag may not be used in advertisements or trademarks,[15] and that "publicly and wilfully burning, mutilating, scrawling on, defiling or trampling" the flag is considered flag desecration.[16] Similarly, the National Flag and National Emblem Ordinance extends the same prohibition toward the national PRC flag.[17][18] The ordinances also allow for the Chief Executive to make stipulations regarding the use of the flag. In stipulations made in 1997, the Chief Executive further specified that the use of the flag in "any trade, calling or profession, or the logo, seal or badge of any non-governmental organisation" is also prohibited unless prior permission was obtained.[12]

The first conviction of flag desecration occurred in 1999. Protesters Ng Kung Siu and Lee Kin Yun wrote the word "Shame" on both the national PRC flag and the Hong Kong flag, and were convicted of violating the National Flag and National Emblem Ordinance and the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance. The Court of Appeal overturned the verdict, ruling that the ordinances were unnecessary restrictions on the freedom of expression and in violation of both the Basic Law and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Upon further appeal, however, the Court of Final Appeal maintained the original guilty verdict, holding that this restriction on the freedom of expression was justifiable in that the protection of the flags played a role in national unity and territorial integrity and constituted a restriction on the mode of expressing one's message but did not interfere with one's freedom to express the same message in other ways.[19]

Leung Kwok-hung, a former member of the Legislative Council and a political activist in Hong Kong, was penalised in February 2001, before he became a member of the Legislative Council, for defiling the flag. He was convicted of three counts of desecrating the flag—for two incidents on 1 July 2000 during the third anniversary of Hong Kong's handover to China and for one incident on 9 July of the same year during a protest against elections to choose the Election Committee, the electoral college which chooses the Chief Executive of Hong Kong. Leung was placed on a good-behaviour bond for 12 months in the sum of HK$3,000.[20]

Zhu Rongchang, a mainland Chinese farmer has been jailed for three weeks after setting fire to a Chinese flag in Hong Kong. Zhu was charged for "publicly and wilfully" burning the Chinese flag at Golden Bauhinia Square in central Hong Kong. The 74-year-old man is reportedly the third person charged for desecrating the Chinese national flag, but he is first to be jailed under the law.[21]

In early 2013, protestors went to the streets flying the old colonial flag demanding more democracy and resignation of Chief Executive Leung Chun Ying. The use of the flag has created concerns from Chinese authorities and request from Leung to stop flying the flag.[22][23] Despite the calls from Leung the old flags are not subject to use restrictions beyond not being allowed to be placed on flagpoles and are freely sold and manufactured in the territory.

Previous flags of Hong Kong

Qing dynasty (1862–1895)

Prior to the secession of Hong Kong to the United Kingdom following the First Opium War via the Treaty of Nanking, Hong Kong fell under the jurisdiction of the government of China and flew the flag and ensign of the Chinese government of the time. Prior to the establishment of the crown colony of Hong Kong, the ruling dynasty in China was the Qing dynasty. Despite being established in 1644, the Qing Empire had no official flags until 1862. Prior to 1898, when the Second Convention of Peking was signed between the Qing Court and the government of the United Kingdom, the New Territories was still Qing land. The flag itself features the "Azure Dragon" on a plain yellow field with the red flaming pearl of the three-legged crow in the upper left corner.[24]

.svg.png.webp)

Qing dynasty flag, 1862–1889

Qing dynasty flag, 1862–1889.svg.png.webp)

Qing dynasty flag, 1889–1912

Qing dynasty flag, 1889–1912

Colonial flags

Prior to Hong Kong's transfer of sovereignty, the flag of Hong Kong was a colonial Blue Ensign flag.[25] The flag of colonial Hong Kong underwent several changes from then until 1997.

Use of Union Flag (1843–1871)

In 1843, a seal representing Hong Kong was instituted. The design was based on a local waterfront scene; three local merchants with their commercial goods are shown on the foreground, a square-rigged ship and a junk occupy the middle ground, while the background consists of conical hills and clouds. In 1868, a Hong Kong flag was produced, a Blue Ensign flag with a badge based on this "local scene", but the design was rejected by Hong Kong Governor Richard Graves MacDonnell.[25]

First colonial flag (1871–1876)

On 3 July 1869, a new design for the Hong Kong flag was commissioned at a cost of £3, which featured a "gentleman in an evening coat who is purchasing tea on the beach at Kowloon". After a brief discussion in the executive council, it was determined that the new design was very problematic and it was not adopted.[26]

In 1870, a "white crown over HK" badge for the Blue Ensign flag was proposed by the Colonial Secretary. The letters "HK" were omitted and the crown became full-colour three years later.[25] It is unclear exactly what the badge looked like during that period of time, but it was unlikely to be the "local scene". It should have been a crown of some sort, which may, or may not, have had the letters "HK" below it. In 1876, the "local scene" badge (Chinese: 阿群帶路圖 Picture of "Ar Kwan" Guiding the British soldier) was re-adopted to the Blue Ensign flag with the Admiralty's approval.[25]

Second colonial flag (1876–1955)

During a government meeting, held in 1911, it was suggested that the name of the colony appear on the flag in both Latin and Chinese scripts. However, this was dismissed as it would "look absurd" to both Chinese and Europeans.[27] The flag which was eventually adopted featured the Blue Ensign together with a "local scene" of traders in the foreground and both European-style and Chinese-style trading ships in the background.

Japanese occupation period (1941–1945)

During the Second World War, Hong Kong was seized and occupied by the Empire of Japan from 1941 to 1945. During the occupation, the Japanese military government used the flag of Japan in its official works in Hong Kong.[28]

Third colonial flag (1955–1959)

The flag was similar in design to that previously used. It featured a British Blue Ensign with a local waterfront scene.

Fourth colonial flag (1959–1997)

A coat of arms for Hong Kong was granted on 21 January 1959 by the College of Arms in London. The Hong Kong flag was revised in the same year to feature the coat of arms in the Blue Ensign flag. This design was used officially from 1959 until Hong Kong's transfer of sovereignty in 1997.[25] Since then, the colonial flag has been appropriated by protestors, such as on the annual 1 July marches for universal suffrage, as a "symbol of antagonism towards the mainland",[29] along with a blue flag featuring the coat of arms, used by those advocating independence. The flag features a British Blue Ensign with the coat of arms of Hong Kong (1959–1997).

Flag used in 1843–1871

Flag used in 1843–1871.svg.png.webp)

Flag used in 1871–1876

Flag used in 1871–1876.svg.png.webp)

Flag used in 1876–1941 and 1945–1955

Flag used in 1876–1941 and 1945–1955.svg.png.webp)

Flag used in 1941–1945

Flag used in 1941–1945.svg.png.webp)

Flag used in 1955–1959

Flag used in 1955–1959.svg.png.webp)

Flag used in 1959–1997

Flag used in 1959–1997

Flags used by government departments

Flags of the governor of Hong Kong

.svg.png.webp)

Flag of the governor of Hong Kong, 1910–1955

Flag of the governor of Hong Kong, 1910–1955.svg.png.webp)

Flag of the governor of Hong Kong, 1955–1959

Flag of the governor of Hong Kong, 1955–1959.svg.png.webp)

Flag of the governor of Hong Kong, 1959–1997

Flag of the governor of Hong Kong, 1959–1997

Hong Kong Regional Council

The flag of the Regional Council represented the governmental body which oversaw matters related to the outlying areas of the territory during the colonial period. The flag itself featured a stylised dark green R at a 45-degree angle on white background.

Hong Kong Urban Council

The flag of the Urban Council represented the governmental body which was responsible for matters pertaining to the urban areas of the territory during the colonial period. The flag itself features a simplified white Bauhinia blakeana on a magenta background.

Flag of the Regional Council

Flag of the Regional Council

Flag of the Urban Council

Flag of the Urban Council

Proposals before the handover

Before Hong Kong's transfer of sovereignty, between 20 May 1987 and 31 March 1988, a contest was held amongst Hong Kong residents to help choose a flag for post-colonial Hong Kong, with 7,147 design submissions, in which 4,489 submissions were about flag designs.[30] Architect Tao Ho was chosen as one of the panel judges to pick Hong Kong's new flag. He recalled that some of the designs had been rather funny and with political twists: "One had a hammer and sickle on one side and a dollar sign on the other."[31] Some designs were rejected because they contained copyrighted materials, for example, the emblem of Urban Council, Hong Kong Arts Festival and Hong Kong Tourism Board.[30] Six designs were chosen as finalists by the judges, but were all later rejected by the PRC. Ho and two others were then asked by the PRC to submit new proposals.[8]

Looking for inspiration, Ho wandered into a garden and picked up a Bauhinia blakeana flower. He observed the symmetry of the five petals, and how their winding pattern conveyed to him a dynamic feeling. This led him to incorporate the flower into the flag to represent Hong Kong.[8] The design was adopted on 4 April 1990 at the Third Session of the Seventh National People's Congress,[2] and the flag was first officially hoisted seconds after midnight on 1 July 1997 in the handover ceremony marking the transfer of sovereignty. It was hoisted together with the national PRC flag, while the Chinese national anthem, "March of the Volunteers", was played. The Union Flag and the colonial Hong Kong flag were lowered seconds before midnight.[7]

See also

Notes

- The offset angle of the top petal is 14° as opposed to 13°48'.

References

- "State Council Gazette Issue No.7 Serial No. 616 (May 26, 1990)" (PDF). www.gov.cn. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Decision of the National People's Congress on the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administration Region of the People's Republic of China". Government of Hong Kong. 4 April 1990. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance". Hong Kong e-Legislation. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Laws and Regulations of the People's Republic of China. China Legal Publishing House. 2001. p. iv. ISBN 7-80083-759-9.

- "Basic Law Full Text". Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance" (PDF). Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Jeffrey Aaronson. "Schedule of Events". Time. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- 忆香港区旗区徽的诞生(上) [Reflecting on the Creation of the Hong Kong SAR Flag and Emblem – Part 1] (in Chinese). Wenhui-xinmin United Press Group. 24 May 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2009. and 忆香港区旗区徽的诞生(下) [Reflecting on the Creation of the Hong Kong SAR Flag and Emblem – Part 2] (in Chinese). Wenhui-xinmin United Press Group. 25 May 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- (Schedule 1 of the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance) "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance". Hong Kong e-Legislation. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- Elihu Lauterpacht; C. J. Greenwood; A. G. Oppenheimer (2002). International Law Reports. Vol. 122. Cambridge University Press. p. 582. ISBN 978-0-521-80775-3.

- (Schedule 5 of the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance) "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance" (PDF). Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "Stipulations for the Display and Use of The National Flag and National Emblem and The Regional Flag and Regional Emblem" (PDF). Protocol Division Government Secretariat of the Hong Kong SAR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Display of the Flags and Emblems". Protocol Division Government Secretariat of the Hong Kong SAR. 6 September 2005. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- (Schedule 4 of the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance) "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance" (PDF). Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- (Section 6 of the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance) "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance" (PDF). Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- (Section 7 of the Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance) "Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance" (PDF). Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "CAP 2401, Section 6 – Prohibition on certain uses of national flag and national emblem". Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "CAP 2401, Section 7 – Protection of the national flag and national emblem". Bilingual Laws Information System. 1 July 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "FINAL APPEAL NO. 4 OF 1999 (CRIMINAL)". Court of Final Appeal. 15 December 1999. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "Annual Report 2001". Hong Kong Journalists Association. 9 August 2001. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- "Hong Kong Jails Chinese Farmer For Flag-Burning". Arab Times. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Alex Lo (5 November 2012). "Flag-wavers have right to be ridiculous". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Joshua But; Tony Cheung (2 November 2012). "Hong Kong chief executive urges people not to wave colonial flag". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Mierzejewski, Dominik; Kowalski, Bartosz (2019). China's Selective Identities: State, Ideology and Culture. Global Political Transitions. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-0164-3. ISBN 978-981-13-0163-6. S2CID 158954624.

- "Colonial Hong Kong". Flags of the World. 18 August 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- "Minutes of Meeting: LegCo 15th April 1912" (PDF). Hong Kong LegCo Archives. The Hong Kong Legislative Council. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Minutes of Meeting: 28th December 1911" (PDF). Hong Kong Legislative Council Archives. Hongkong Legislative Council. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Carroll, John M. (2007). A Concise History of Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7425-7469-4.

- A.T. (4 July 2012). "Free speech in Hong Kong: Show of strength". Analects. Hong Kong. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- 香港区旗区徽诞生记. China Art News. 1 January 2007. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- Andrea Hamilton. "Bringing You The Handover: Meet some of the most important men and women working behind the scenes". Asiaweek. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

External links

- Hong Kong at Flags of the World

- About the National Flag Archived 7 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine – webpage hosted on the website of the Protocol Division Government Secretariat

- Regional Flag and Regional Emblem Ordinance at elegislation.gov.hk