Salt (chemistry)

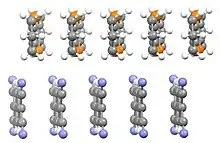

In chemistry, a salt is a chemical compound consisting of an ionic assembly of positively charged cations and negatively charged anions, which results in a compound with no net electric charge.[1] A common example is table salt, with positively charged sodium ions and negatively charged chloride ions.

The component ions in a salt compound can be either inorganic, such as chloride (Cl−), or organic, such as acetate (CH

3COO−

). Each ion can be either monatomic, such as fluoride (F−), or polyatomic, such as sulfate (SO2−

4).

Types of salt

Salts can be classified in a variety of ways. Salts that produce hydroxide ions when dissolved in water are called alkali salts and salts that produce hydrogen ions when dissolved in water are called acid salts. Neutral salts are those salts that are neither acidic nor alkaline. Zwitterions contain an anionic and a cationic centre in the same molecule, but are not considered salts. Examples of zwitterions are amino acids, many metabolites, peptides, and proteins.[2]

Properties

Color

Solid salts tend to be transparent, as illustrated by sodium chloride. In many cases, the apparent opacity or transparency is related only to the difference in size of the individual monocrystals. Since light reflects from the grain boundaries (boundaries between crystallites), larger single crystals tend to be transparent, while the polycrystalline aggregates look like opaque powders or masses.

Salts exist in many different colors, which arise either from their constituent anions, cations or solvates. For example:

- sodium chromate is made yellow by the chromate ion

- potassium dichromate is made orange by the dichromate ion

- cobalt nitrate is made red by the chromophore of hydrated cobalt(II) ([Co(H2O)6]2+).

- copper sulfate is made blue by the copper(II) chromophore

- potassium permanganate is made violet by the permanganate anion.

- nickel chloride is typically made green by the hydrated nickel(II) chloride [NiCl2(H2O)4]

- sodium chloride, magnesium sulfate heptahydrate appear colorless or white because the constituent cations and anions do not absorb light in the part of the spectrum that is visible to humans.

Few minerals are salts, because they would be solubilized by water. Similarly, inorganic pigments tend not to be salts, because insolubility is required for fastness. Some organic dyes are salts, but they are virtually insoluble in water.

Taste

Different salts can elicit all five basic tastes, e.g., salty (sodium chloride), sweet (lead diacetate, which will cause lead poisoning if ingested), sour (potassium bitartrate), bitter (magnesium sulfate), and umami or savory (monosodium glutamate).

Odor

Salts of strong acids and strong bases ("strong salts") are non-volatile and often odorless, whereas salts of either weak acids or weak bases ("weak salts") may smell like the conjugate acid (e.g., acetates like acetic acid (vinegar) and cyanides like hydrogen cyanide (almonds)) or the conjugate base (e.g., ammonium salts like ammonia) of the component ions. That slow, partial decomposition is usually accelerated by the presence of water, since hydrolysis is the other half of the reversible reaction equation of formation of weak salts.

Solubility

Many ionic compounds exhibit significant solubility in water or other polar solvents. Unlike molecular compounds, salts dissociate in solution into anionic and cationic components. The lattice energy, the cohesive forces between these ions within a solid, determines the solubility. The solubility is dependent on how well each ion interacts with the solvent, so certain patterns become apparent. For example, salts of sodium, potassium and ammonium are usually soluble in water. Notable exceptions include ammonium hexachloroplatinate and potassium cobaltinitrite. Most nitrates and many sulfates are water-soluble. Exceptions include barium sulfate, calcium sulfate (sparingly soluble), and lead(II) sulfate, where the 2+/2− pairing leads to high lattice energies. For similar reasons, most metal carbonates are not soluble in water. Some soluble carbonate salts are: sodium carbonate, potassium carbonate and ammonium carbonate.

Conductivity

Salts are characteristically insulators. Molten salts or solutions of salts conduct electricity. For this reason, liquified (molten) salts and solutions containing dissolved salts (e.g., sodium chloride in water) can be used as electrolytes.

Melting point

Salts characteristically have high melting points. For example, sodium chloride melts at 801 °C. Some salts with low lattice energies are liquid at or near room temperature. These include molten salts, which are usually mixtures of salts, and ionic liquids, which usually contain organic cations. These liquids exhibit unusual properties as solvents.

Nomenclature

The name of a salt starts with the name of the cation (e.g., sodium or ammonium) followed by the name of the anion (e.g., chloride or acetate). Salts are often referred to only by the name of the cation (e.g., sodium salt or ammonium salt) or by the name of the anion (e.g., chloride salt or acetate salt).

Common salt-forming cations include:

- Ammonium NH+

4 - Calcium Ca2+

- Iron Fe2+

and Fe3+ - Magnesium Mg2+

- Potassium K+

- Pyridinium C

5H

5NH+ - Quaternary ammonium NR+

4, R being an alkyl group or an aryl group - Sodium Na+

- Copper Cu2+

Common salt-forming anions (parent acids in parentheses where available) include:

- Acetate CH

3COO−

(acetic acid) - Carbonate CO2−

3 (carbonic acid) - Chloride Cl−

(hydrochloric acid) - Citrate HOC(COO−

)(CH

2COO−

)

2 (citric acid) - Cyanide C≡N−

(hydrocyanic acid) - Fluoride F−

(hydrofluoric acid) - Nitrate NO−

3 (nitric acid) - Nitrite NO−

2 (nitrous acid) - Oxide O2−

(water) - Phosphate PO3−

4 (phosphoric acid) - Sulfate SO2−

4 (sulfuric acid)

Salts with varying number of hydrogen atoms replaced by cations as compared to their parent acid can be referred to as monobasic, dibasic, or tribasic, identifying that one, two, or three hydrogen atoms have been replaced; polybasic salts refer to those with more than one hydrogen atom replaced. Examples include:

- Sodium phosphate monobasic (NaH2PO4)

- Sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4)

- Sodium phosphate tribasic (Na3PO4)

Formation

_sulfate.jpg.webp)

Salts are formed by a chemical reaction between:

- A base and an acid, e.g., NH3 + HCl → NH4Cl

- A metal and an acid, e.g., Mg + H2SO4 → MgSO4 + H2

- A metal and a non-metal, e.g., Ca + Cl2 → CaCl2

- A base and an acid anhydride, e.g., 2 NaOH + Cl2O → 2 NaClO + H2O

- An acid and a base anhydride, e.g., 2 HNO3 + Na2O → 2 NaNO3 + H2O

- In the salt metathesis reaction where two different salts are mixed in water, their ions recombine, and the new salt is insoluble and precipitates. For example:

- Pb(NO3)2 + Na2SO4 → PbSO4↓ + 2 NaNO3

Strong salt

Strong salts or strong electrolyte salts are chemical salts composed of strong electrolytes. These ionic compounds dissociate completely in water. They are generally odorless and nonvolatile.

Strong salts start with Na__, K__, NH4__, or they end with __NO3, __ClO4, or __CH3COO. Most group 1 and 2 metals form strong salts. Strong salts are especially useful when creating conductive compounds as their constituent ions allow for greater conductivity.

Weak salt

Weak salts or "weak electrolyte salts" are, as the name suggests, composed of weak electrolytes. They are generally more volatile than strong salts. They may be similar in odor to the acid or base they are derived from. For example, sodium acetate, CH3COONa, smells similar to acetic acid CH3COOH.

See also

- Bresle method (the method used to test for salt presence during coating applications)

- Carboxylate

- Fireworks/pyrotechnics (salts are what give color to fireworks)

- Halide

- Ionic bonds

- Natron

- Salinity

References

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "salt". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05447

- Voet, D. & Voet, J. G. (2005). Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 68. ISBN 9780471193500. Archived from the original on 2007-09-11.

- D. Chasseau; G. Comberton; J. Gaultier; C. Hauw (1978). "Réexamen de la structure du complexe hexaméthylène-tétrathiafulvalène-tétracyanoquinodiméthane". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 34 (2): 689. doi:10.1107/S0567740878003830.

- Mark Kurlansky (2002). Salt: A World History. Walker Publishing Company. ISBN 0-14-200161-9.