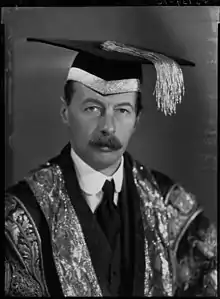

Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire

Edward William Spencer Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire, KG, MBE, TD (6 May 1895 – 26 November 1950), known as the Marquess of Hartington from 1908 to 1938, was a British politician. He was the head of the Devonshire branch of the House of Cavendish. He had careers with the army and in politics and was a senior freemason. His sudden death, apparently of a heart attack at the age of fifty-five, occurred in the presence of the suspected serial killer John Bodkin Adams.

The Duke of Devonshire | |

|---|---|

| |

| Under-Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs | |

| In office 1936–1940 | |

| Monarchs | Edward VIII George VI |

| Preceded by | Douglas Hacking |

| Succeeded by | Geoffrey Shakespeare |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 May 1895 St George in the East, Stepney, London |

| Died | 26 November 1950 (aged 55) Eastbourne |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse | Lady Mary Gascoyne-Cecil |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

Early life

He was born in the parish of St George in the East, Stepney, London, the son of Victor Cavendish and his wife, Lady Evelyn Petty-Fitzmaurice. In 1908, his father Victor succeeded as the 9th Duke of Devonshire, thus Edward was styled by the courtesy title Marquess of Hartington. Lord Hartington was educated at Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge.[1]

He was, after his father's death, the owner of Chatsworth House, and one of the largest private landowners in both Great Britain and Ireland.

Military career

The then Marquess of Hartington began service with the Territorial Army as a second lieutenant in the Derbyshire Yeomanry in 1913.[2]

Mobilised at the outbreak of the First World War, he was an aide-de-camp (ADC) on the Personal Staff[3] at the British Expeditionary Force's General Headquarters. In 1916, when promoted captain, he rejoined his regiment, in Egypt, and served in the latter stages of the Dardanelles campaign. He then returned to France, became attached to Military Intelligence, then to the War Office and the British Military Mission in Paris, and was twice mentioned in despatches.[1] In 1919 he served on the British peace delegation that attended the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and was appointed MBE.[1] He also became a knight of the French Legion of Honour.[1]

He continued serving after the war with his regiment, which became 24 (Derbyshire Yeomanry) Armoured Car Company of the Royal Tank Regiment in 1923. He was promoted major in 1932, and became lieutenant colonel in command in 1935.[3] He was awarded the Territorial Decoration.[1] He was also Honorary Colonel of the 6th Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters from 1917 to 1937, and of its successor, the 40th (Sherwood Foresters) Anti-Aircraft Battalion of the Royal Engineers.[3]

Political career

He unsuccessfully stood as a Conservative parliamentary candidate twice, in the 1918 general election for North East Derbyshire and in 1922 for West Derbyshire, before gaining the latter seat in 1923 and holding it until he succeeded to his father's peerage and entered the House of Lords in 1938. He was subsequently a minister in Winston Churchill's wartime government as a Parliamentary Under Secretary of State, for India and Burma (1940–1942) and for the Colonies (1942–1945).[1]

He also served in Derbyshire local government. He was appointed a JP for the county in 1917, and a Deputy Lieutenant in 1936,[4] ultimately becoming the county's Lord Lieutenant from 1938 until his death.[1] He also served as Mayor of Buxton in 1920–21.[4]

Other civil posts

He was chairman of the Overseas Settlement Board in 1936 and was High Steward of the University of Cambridge and Chancellor of the University of Leeds from 1938 until 1950.[1] He also had company directorships with The Alliance Insurance Company of Britain and the Bank of Australasia.[4] He served as president of the Zoological Society of London in 1948.[1]

He was a freemason and was Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England from 1947 to 1950.

Marriage and children

In 1917, he married Lady Mary Gascoyne-Cecil, granddaughter of Prime Minister Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury. They had five children:[5]

- William John Robert Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington (10 December 1917 – 10 September 1944), killed in action in World War II; married Kathleen Kennedy, sister of John F. Kennedy

- Andrew Robert Buxton Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire (2 January 1920 – 3 May 2004), married Hon. Deborah Freeman-Mitford, youngest daughter of David Freeman-Mitford, 2nd Baron Redesdale

- Lady Mary Cavendish (6 November 1922 – 17 November 1922)

- Lady Elizabeth Georgiana Alice Cavendish (24 April 1926 – 15 September 2018)

- Lady Anne Evelyn Beatrice Cavendish (6 November 1927 – 9 August 2010), a prison visitor; married Michael Lambert Tree[6]

The Duke's sister Dorothy was married to Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. The Duke's younger brother Charles was married to dancer Adele Astaire, sister of Fred Astaire.

Death

On 26 November 1950, he suffered a heart attack and died in Eastbourne in the presence of his general practitioner, John Bodkin Adams, the suspected serial killer.[7] Despite the fact that the duke had not seen a doctor in the 14 days before his death, the coroner was not notified as he should have been. Adams signed the death certificate stating that the Duke died of natural causes. Thirteen days earlier, Edith Alice Morrell – another patient of Adams – had also died. Historian Pamela Cullen speculates that as the Duke was the head of British freemasonry, Adams – a member of the fundamentalist Plymouth Brethren – would have been motivated to withhold the necessary vital treatment,[8] since the "Grandmaster of England would have been seen by some of the Plymouth Brethren as Satan incarnate".[9] No proper police investigation was ever conducted into the death, but the duke's son, Andrew, later said "it should perhaps be noted that this doctor was not appointed to look after the health of my two younger sisters, who were then in their teens";[7] Adams had a reputation for grooming older patients in order to extract bequests.

Adams was tried in 1957 for Morrell's murder but controversially acquitted.[7][10] The prosecutor was Attorney-General Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller, a distant cousin of the Duke (via their shared ancestor, George Cavendish).[7] Cullen has questioned why Manningham-Buller failed to question Adams regarding the Duke's death, and suggests that he was wary of drawing attention to Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (the Duke's brother-in-law) and specifically to his wife who was having an extramarital affair with Robert Boothby at the time.[11]

Home Office pathologist Francis Camps linked Adams to 163 suspicious deaths in total, which would make him a precursor to Harold Shipman.[7]

The Duke's body was buried in the churchyard at Edensor, Derbyshire, near Chatsworth.

Estate

In 1946 the Duke transferred most of his assets to his only surviving son in an attempt to avoid a repeat of the heavy death duties which the 9th Duke had had to pay in 1908. The Duke's surprise death less than four years later meant that his estate had to pay 80% death duties on the value of the entire estate. Had he lived longer, the value assessed to tax would have been progressively reduced to zero. The tax liability led to the transfer of Hardwick Hall to the National Trust, and the sale of many of the Devonshires' accumulated assets, including tens of thousands of acres of land, and many works of art and rare books.[12] Whilst the majority of the Duke's property transferred to the next Duke, his private funds of £796,473 8s. 9d. were willed to his widow Mary Alice, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire.

See also

References

- Who Was Who, 1941–1950. A & C Black. 1952. p. 310.

- Kelly's Handbook of the Titled, Landed and Official Classes, 1916. Kelly's. p. 714.

- Kelly's Handbook of the Titled, Official and Landed Classes, 1948. Kelly's. p. 626.

- Kelly's Handbook to the Titled, Landed and Official Classes, 1948. Kelly's. p. 626.

- Mosley, Charles, editor. Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes. Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003

- Eve Colpus, 'Tree, Lady Anne Evelyn Beatrice (1927–2010)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Jan 2014; online edn, Jan 2015 accessed 20 April 2017

- Cullen, Pamela V., Stranger in Blood: The Case Files on Dr John Bodkin Adams, London, Elliott & Thompson, 2006, ISBN 1-904027-19-9.

- Cullen, pp. 97–101.

- Cullen, p. 100.

- Devlin, Patrick. Easing the passing: The trial of Doctor John Bodkin Adams, London, The Bodley Head, 1985.

- Cullen, p. 617.

- "GREAT BRITAIN: Death and Taxes". Time. 26 August 1957. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011.