1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery

The 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery was the first protest against enslavement of Africans made by a religious body in the Thirteen Colonies. Francis Daniel Pastorius authored the petition; he and three other Quakers living in Germantown, Pennsylvania (now part of Philadelphia), signed it on behalf of the Germantown Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends. Clearly a highly controversial document, Friends forwarded it up the hierarchical chain of their administrative structure—monthly, quarterly, and yearly meetings—without either approving or rejecting it. The petition effectively disappeared for 150 years into Philadelphia Yearly Meeting's capacious archives; but upon rediscovery in 1844 by Philadelphia antiquarian Nathan Kite, latter-day abolitionists published it in 1844 in The Friend, (Vol. XVII, No. 16.) in support of their antislavery agitation.

| 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery | |

|---|---|

The petition was the first

American public document to protest slavery. It was also one of the first written public declarations of universal human rights. | |

| Created | April 1688 |

| Location | Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections |

| Signatories | Francis Daniel Pastorius, Garret Hendericks, Derick op den Graeff, and Abraham op den Graeff |

| Purpose | Protest against the institution of slavery. |

Historical background

The colony of Pennsylvania was founded in 1682 by William Penn as a place where people from any country and faith could settle, free from religious persecution. In payment of a debt to Penn's father, Penn had received from King Charles II a large land grant west of New Jersey which Charles II named Pennsylvania after William's father, Admiral William Penn. Penn had become a friend of George Fox, the founder of the Society of Friends, who were pejoratively nicknamed "Quakers" because they described themselves as quaking and trembling in fear of the Lord. Penn had converted to Quakerism and had been imprisoned several times for his beliefs. Charles II allowed Penn to establish a proprietary colony where Penn appointed the governor and judges but established an otherwise democratic system of government with freedom of religion, fair trials, elected representatives, and separation of church and state.

From 1660 to 1680, several Quakers including William Penn visited the United Provinces and the Rhine valley of what would later become Germany, and organized gatherings where they preached the Quaker testimony. Many people, including some who had been Mennonites in Krefeld and Kriegsheim (now part of the modern Mennonite congregation of Monsheim, Germany), in the German "Palatinate", converted to the new Quaker faith. Among them was Francis Daniel Pastorius, a young German born near Würzburg to a family of elite officeholders. After training as an attorney, Pastorius sought spiritual release from his lucrative but uninspiring practice with the local gentry, and he turned inward looking for a philosophical purity in his life. He was attracted to Penn's colony as a place where religious freedom would allow him to start afresh a life free from "libertinism and sins of the European world." Meanwhile, the Mennonites and Quakers in the Netherlands and along the Rhine valley were often fined or imprisoned for publicly practicing a faith other than the officially recognized Reformed Church, Catholicism and Lutheranism.

In 1681, Penn invited immigrants from Europe to the new colony. He arrived in 1682, had the land surveyed, organized Philadelphia as a welcoming town laid out as a grid with many green spaces, and profited by selling lots. Soon, the waterfront was a bustle of activity, town streets were laid out with houses built on narrow lots, and churches of several different faiths were established. The town merchants traded with the largely Quaker colony of West Jersey. The town and surrounding countryside prospered.

The German settlement

In 1683, Pastorius was delegated authority to purchase land in the new Pennsylvania colony by a group of men from Frankfurt who intended to emigrate. He traveled to Philadelphia in August 1683, having purchased a warrant from Penn's agent on behalf of the Frankfurt men who had supplied the funds. In October, 1683, thirteen German-Dutch families from Krefeld in the Rhine valley arrived with their own land claim. Seizing upon a chance to create a viable German-speaking town, Pastorius negotiated with Penn to combine the two claims. As it turned out, the people from the Frankfurt Company never emigrated to the new colony, but more Quakers and Mennonites came from the Rhine valley and Pastorius's ambitious plan for a German-speaking town near Philadelphia grew and became real.

Pastorius had devised a simple plan for a town, with lots parceled out along one long main thoroughfare, where settlers could build their houses. He required land good for tilling because the emigrants would need to grow their own food to survive. Pastorius and Penn became good friends, and they often discussed plans for the new settlement over dinner. The land originally promised to Pastorius was supposed to be level and along a navigable river, and Pastorius had paid for 6,000 contiguous acres (24 km2). However a suitable tract of land near Philadelphia was unavailable on the Delaware River, because level ground there was valuable and most of it had already been sold. Penn suggested land near the Schuylkill Falls (East Falls), but it was too steep for Pastorius's plan, so as an alternative Penn suggested land a little further east, near the top of a gentle hill between two creeks, and Pastorius agreed. Germantown was thus founded along a Lenni Lenape trail four miles (6 km) north of Philadelphia, between the Wissahickon and Wingohocking creeks. Pastorius had the land surveyed, and over the first winter the families lived in downtown Philadelphia while struggling to clear the land for their makeshift log houses. Germantown became a separate and self-sufficient town of Dutch and German speakers.

The thirteen original Krefelder families were Mennonites who had become Quakers in their native Holland before they arrived in the new Pennsylvania colony. Because they had been persecuted in their own land on account of their beliefs they understood the value of a community founded on religious toleration. Unlike Pastorius, they were not wealthy, but were skilled craftsmen who knew they would have to work hard for a living. By trade they were carpenters, weavers, dyers, tailors, and shoemakers, so they were not fully prepared for the hard work of clearing the forest. Over the first year they cleared land and planted crops for food and flax for weaving. They set up looms and soon were producing linen cloth that sold widely throughout the colonies.

The issue of slavery

Some of the early settlers of Philadelphia and its surrounding towns were wealthy and purchased African slaves to work on their farms. Although many such slaveowners also had immigrated to escape religious persecution, they saw no contradiction in owning slaves. Although serfdom had already been abolished in northwestern Europe by 1500, servitude was still ubiquitous, and sometimes under harsh conditions. Many immigrants to the new colony were indentured servants, who had signed an agreement to work for several years in exchange for being transported via a passenger ship to the new colony. Slavery was widespread in the American colonies, and local slave markets ensured the ease of purchasing slaves to the general populace. The Atlantic slave trade was beginning to rapidly expand, and many settlers thought it necessary for economic growth in the colonies. Many slave ship owners and captains made large profits transporting slaves from Africa to the Caribbean and mainland North America. William Penn oversaw the economic progress of his colony and once proudly declared that during the course of a year Philadelphia had received ten slave ships.

The first settlers of Germantown were soon joined by several more Quaker and Mennonite families from Kriegsheim (Monsheim), also in the Rhine valley, who were ethnic Germans but spoke a similar dialect to the Hollanders from Krefeld. Some out of pragmatism attended the local Quaker Meetings held in the newly built homes of immigrants, becoming involved and accepted in the Philadelphia Quaker community, and eventually joining as members. However, in several ways they felt themselves outsiders, which allowed them to question the social values in the nascent colony. Some attended the Quaker Meeting temporarily while they waited for a Mennonite minister to arrive, and then helped to build the first Mennonite Meetinghouse. The town prospered and grew, and a Quaker Meeting was organized at Thones Kunders's house, under the care of Dublin (Abington Meeting). By 1686 a Quaker Meetinghouse was constructed near the current site of Germantown Friends Meeting.

The German-Dutch settlers were unaccustomed to owning slaves, although from the shortage of labor they understood why slavery was required to ensure the economic prosperity of the colony. Slaves and indentured servants were a valuable asset for a farmer because they were not paid. Yet the German-Dutch settlers refused to buy slaves themselves and quickly saw the contradiction in the slave trade and in farmers who forced people to work. Although in their native Germany and Holland the Krefelders had been persecuted because of their beliefs, only people who had been convicted of a crime could be forced to work in servitude. In what turned out to be a revolutionary leap of insight, the Germantowners saw a fundamental similarity between the right to be free from persecution on account of their beliefs and the right to be free from being forced to work against their will.

Contents of the petition

In 1688, five years after Germantown was founded, Pastorius and three other men petitioned the Dublin Quaker Meeting. The men gathered at Thones Kunders's house and wrote a petition based upon the Bible's Golden Rule, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you," urging the Meeting to abolish slavery. It is an unconventional text in that it avoids the expected salutation to fellow Quakers and does not contain references to Jesus and God. It argues that every human, regardless of belief, color, or ethnicity, has rights that should not be violated.

Throughout the petition the reference to the Golden Rule is used to argue against slavery and for universal human rights. On first reading, the argument presented in the petition seems indirect. Nowhere is the Meeting specifically asked to condemn the practice of slavery. Instead, in reference to the Golden Rule, the four men ask why Christians are allowed to buy and own slaves, almost in mock sarcasm, to get the slaveowners to see their point. In doing so, it arguably was very successful, but it would be easy to miss the sophistication of their argument. They emphatically argue that in their society the capture and sale of ordinary people as slaves, where husband, wife and children are separated, would not be tolerated, again referring to the Golden Rule.

The four men also assert that according to the Golden Rule, the slaves would have the right to revolt, and that inviting more people to the new land would be difficult if prospective settlers saw the contradiction inherent in slavery. In mentioning the possibility of a slave revolt, they clearly were suggesting to that slavery would discourage potential settlers from emigrating to the American colonies. In the Caribbean colonies there had been many slave revolts over several decades, so the possibility was real. However, the power of the argument for potential settlers from Europe was more than the fear of a revolt—it was that any such revolt would be justifiable according to the Golden Rule. This logic strengthened the newly defined universal rights, which applied to all humans, not just the "civilized". The petition has several examples of such counter-intuitive but forceful arguments to push the slave-owning reader off his balance.

The petition contains several points of difficulty for the reader unfamiliar with history. First, the petition's grammar seems unusual today but reflects the Krefelders' incomplete knowledge of English as well as typical pre-modern use of variable spelling. The original wording includes "ye." which is a contraction of the word "the", and might be confused with the second person plural "ye" that was in wide use at the time.

Second, the petition mentions Turks as an example of a people who might take someone on a ship into slavery in the Ottoman Empire. The four men were referring to the widely known stories of Barbary pirates who had established outposts on the coast of North Africa and for hundreds of years had plundered ships. After the Muslims were driven out of Spain in 1492 they raided the Spanish coast and the Spanish countered with more attacks. The Barbary pirates in the period (1518–1587) were allied with the Ottoman authorities and captured slaves to be brought back to North Africa or Turkey. Thus in their early period, their motivation was political. In the later period during the 17th century the North African pirate communities became more independent and lived mainly on plunder so the motivation for piracy was mainly economic. In that period up to 20,000 captured Christians were said to be kept as slaves in Algiers. The slave raiders traveled throughout the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic, often taking slaves from Italy and Spain, but ranging as far north as Ireland (see Sack of Baltimore etc.). Among the Barbary pirates were renegades from Northern Europe who had converted to Islam. Some English, French, and Germans were allowed to pay their way out of slavery and so brought back the stories of marauding pirates capturing slaves. At the time that the Petition was written, a number of Friends were enslaved in Morocco, including the captain of the ship that had brought Pastorius and his compatriots to Pennsylvania.[1]

The petition's mention of this point, then, is another example of their sophisticated reasoning. The widely circulated stories of slavery on the Barbary Coast were true, for Europeans had been the prey of political enemies and renegades who had captured them as slaves. Indeed, in the year that the petition was written, a number of Quakers were enslaved in Morocco.[2] This analogy in the first paragraph of the petition cast the Atlantic slave trade in a questionable light. The four authors expressed their belief that slaves had social and political equality with ordinary citizens.

Third, the petition refers to the black slaves as "negers", which was a German and Dutch word meaning black or negro. In its 1688 usage the term was simply descriptive and not in any way derogatory. Throughout the petition the four men show respect for enslaved people and declare them equals.

Effect of the document

The four men presented their petition at the local Monthly Meeting at Dublin (Abington), but it is not clear what they expected to happen. Although they were accepted in the Quaker community, they were outsiders who could not speak or write fluently in English, and they also had a fresh view of slavery that was unique to Germantown. They must have understood from the beginning that it would be difficult to force the whole colony to abolish slavery, as it was generally believed that the colony's prosperity depended on slavery. It is not clear whether the four men expected the local Meeting to affirm their view, because they knew that nearby Meetings might not in be in agreement, and consequences would be far-reaching. The Meeting decided that although the issue was fundamental and just, it was too difficult and consequential for them to judge, and would need to be considered further. In the usual manner the Meeting sent the petition on to the Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting, where it was again considered and sent on to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (held in Burlington, NJ). Realizing that the abolition of slavery would have a wide and overreaching impact on the entire colony, none of the Meetings wanted to pass judgment on such a "weighty matter." PYM minuted that they would send the petition to London Yearly Meeting, without mentioning whether they actually did so, and on this point no direct evidence has been discovered. The minutes of London Yearly Meeting do not mention the petition directly, apparently skirting the issue.

The practice of slavery continued and was tolerated in Quaker society in the years immediately following the 1688 petition. Some of the authors continued to protest against slavery, but for a decade their efforts were rejected. Germantown continued to prosper, growing in population and economic strength, becoming widely known for the quality of its products such as paper and woven cloth. Eventually several of the original Krefelders rejoined the Mennonites and moved away from Germantown at least in part because of their insistence not to side with slave-owners. Several other petitions and protests were written by Quakers against slavery in the next several decades, but were based on racist or practical arguments of inferiority and intolerance. Some of the protests became entangled with politics and theology and as a result were dismissed by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, confusing the issue. Almost three decades passed before another Quaker petition against slavery was written with sophistication comparable to the Germantown 1688 petition. But the Germantowners' condemnation of slavery continued, and their moral leadership on the issue influenced Quaker abolitionists and Philadelphia society.

Gradually over the next century, due to the efforts of many dedicated Quakers such as Benjamin Lay, John Woolman, and Anthony Benezet, Quakers became convinced of the essential wrongness of the institution of slavery.[3] Many of the Quaker abolitionists published their articles anonymously in Benjamin Franklin's newspaper. In 1776 a proclamation was written by Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banning the owning of slaves.[4] By that time, many Quaker monthly meetings in the Delaware Valley were attempting to help freed slaves by providing funds for them to start businesses and encouraging them to attend Quaker meetings and educate their children. Villages were setup in places such as Lima, Pennsylvania, where released slaves could settle with support from local families involved in the anti-slavery movement. The well-known Van Leer family helped set up lots in Lima, for newly freed slaves and people who would support them.[5]

Historical and social importance

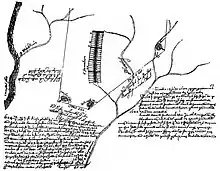

The 1688 petition was the first American document of its kind that made a plea for equal human rights for everyone.[6][7] It compelled a higher standard of reasoning about fairness and equality that continued to grow in Pennsylvania and the other colonies with the Declaration of Independence and the abolitionist and suffrage movements, eventually giving rise to Lincoln's reference to human rights in the Gettysburg Address. The 1688 petition was set aside and forgotten until 1844 when it was re-discovered and became a focus of the burgeoning abolitionist movement in the United States. After a century of public exposure, it was misplaced and once more re-discovered in March 2005 in the vault at Arch Street Meetinghouse. At that time it was in deteriorating condition, with tears at the edges, paper tape covering voids and handwriting where the petition had originally been folded, and its oak gall ink slowly fading into gray. To preserve the document for future generations, it was treated at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) in downtown Philadelphia. CCAHA conservator Morgan Zinsmeister removed previous repairs and reduced centuries of old and discolored adhesives with various poultices and enzymatic solutions. Acidity and discoloration in the paper were reduced through aqueous treatment. Repairs were made with acrylic-toned Japanese papers that were carefully applied to bridge the voids. Finally, the petition was photographed at high resolution and then encapsulated along its edges (not laminated) between sheets of inert polyester film. The petition was shown at an exhibit of original rare American documents at the National Constitution Center on Independence Mall in the summer of 2007. It currently resides at Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections, the joint repository (with Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College) for the records of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Today the 1688 petition is for many a powerful reminder about the basis for freedom and equality for all.

Notes

- Meggitt, Justin J. (2013). "Early Quakers and Islam: Slavery, Apocalyptic and Christian-Muslim Encounters in the Seventeenth Century" (PDF). Uppsala: Swedish Science Press. p. 76. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015.

- See Tuke, Samuel. 1848. Account of the Slavery of Friends in the Barbary States Towards the Close of the Seventeenth Century. London: Edward Marsh.

- An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery - March 1, 1780, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

- Williams, William H. "Slavery and Freedom in Delaware, 1639-1865", Rowman & Littlefield, 1999, ISBN 0-8420-2847-1.

- Lemon, John "Jack" (January 20, 2022). "The Village of Lima". Van Leer Archives. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- Gerbner. "Quaker Roots". Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- Gross, Leonard and Gleysteen, Jan, "Colonial Germantown Mennonites", Telford, PA: Cascadia, 2007, ISBN 1-931038-41-4.

References

- Online images of the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery; Bryn Mawr College

- Carey, Brycchan, From Peace to Freedom: Quaker Rhetoric and the Birth of American Antislavery, 1657-1761. Yale University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780300180770.

- Gerbner, Katharine, "We are against the traffick of mens-body: The Germantown Quaker Protest of 1688 and the Origins of American Abolitionism", in Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies (Spring 2007).

- Introductory text prepared by Germantown Friends Meeting Working Group on the 1688 Petition Against Slavery.

- Nash, Gary B., and Soderlund, Jean R. Freedom by Degrees: Emancipation in Pennsylvania and its aftermath, Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-19-504583-1.

- Jenkins, Charles F, The Guide Book to Historic Germantown, Site and Relic Society, Germantown, 1915.

- Kite, Nathan (1844) "First Germantown Friends", in "The Friend" (January 13, 1844; Vol. XVII, No. 16).

- Lane, Raymond, M. "In Pa., Slavery Protest Came Early," The Washington Post (April 22, 2009).

- Learned, Marion Dexter, The Life of Francis Daniel Pastorius, the Founder of Germantown, Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1908.

- Pennypacker, Samuel W, "The Settlement of Germantown and the Beginning of the German Emigration to North America", Philadelphia, William Campbell, 1899.

- Ruth, John L., "The Emigration From Krefeld to Pennsylvania 1683," an article in Mennonite Quarterly Review, Vol. LVII, #4, October 1983.

- Ward, Townsend, "The Germantown Road and its Associations", in Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1881, Vol. V, No. 1.

- Williams, William H. "Slavery and Freedom in Delaware, 1639-1865", Rowman & Littlefield, 1999. ISBN 0-8420-2847-1

- Wolf, Stephanie Grauman, Urban Village: Population, Community, and Family Structure in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1683-1800. Princeton University Press (May 1, 1980); ISBN 0-691-00590-7.

External links

- Quaker Protest Against Slavery in the New World scan and transcription of manuscript held by Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections