174th Tunnelling Company

The 174th Tunnelling Company was one of the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers created by the British Army during World War I. The tunnelling units were occupied in offensive and defensive mining involving the placing and maintaining of mines under enemy lines, as well as other underground work such as the construction of deep dugouts for troop accommodation, the digging of subways, saps (a narrow trench dug to approach enemy trenches), cable trenches and underground chambers for signals and medical services.[1]

| 174th Tunnelling Company | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | World War I |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Royal Engineer tunnelling company |

| Role | military engineering, tunnel warfare |

| Nickname(s) | "The Moles" |

| Engagements | World War I Battle of the Somme Spring Offensive 1918 |

Background

By January 1915 it had become evident to the BEF at the Western Front that the Germans were mining to a planned system. As the British had failed to develop suitable counter-tactics or underground listening devices before the war, field marshals French and Kitchener agreed to investigate the suitability of forming British mining units.[2] Following consultations between the Engineer-in-Chief of the BEF, Brigadier George Fowke, and the mining specialist John Norton-Griffiths, the War Office formally approved the tunnelling company scheme on 19 February 1915.[2]

Norton-Griffiths ensured that tunnelling companies numbers 170 to 177 were ready for deployment in mid-February 1915.[3] In the spring of that year, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and The Bluff which required the deployment of new drafts of tunnellers for several months after the formation of the first eight companies. The lack of suitably experienced men led to some tunnelling companies starting work later than others. The number of units available to the BEF was also restricted by the need to provide effective counter-measures to the German mining activities.[4] To make the tunnels safer and quicker to deploy, the British Army enlisted experienced coal miners, many outside their nominal recruitment policy. The first nine companies, numbers 170 to 178, were each commanded by a regular Royal Engineers officer. These companies each comprised 5 officers and 269 sappers; they were aided by additional infantrymen who were temporarily attached to the tunnellers as required, which almost doubled their numbers.[2] The success of the first tunnelling companies formed under Norton-Griffiths' command led to mining being made a separate branch of the Engineer-in-Chief's office under Major-General S.R. Rice, and the appointment of an 'Inspector of Mines' at the GHQ Saint-Omer office of the Engineer-in-Chief.[2] A second group of tunnelling companies were formed from Welsh miners from the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the Monmouthshire Regiment, who were attached to the 1st Northumberland Field Company of the Royal Engineers, which was a Territorial unit.[5] The formation of twelve new tunnelling companies, between July and October 1915, helped to bring more men into action in other parts of the Western Front.[4]

Most tunnelling companies were formed under Norton-Griffiths' leadership during 1915, and one more was added in 1916.[1] On 10 September 1915, the British government sent an appeal to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand to raise tunnelling companies in the Dominions of the British Empire. On 17 September, New Zealand became the first Dominion to agree the formation of a tunnelling unit. The New Zealand Tunnelling Company arrived at Plymouth on 3 February 1916 and was deployed to the Western Front in northern France.[6] A Canadian unit was formed from men on the battlefield, plus two other companies trained in Canada and then shipped to France. Three Australian tunnelling companies were formed by March 1916, resulting in 30 tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers being available by the summer of 1916.[1]

Unit history

Formation

From its formation in March 1915 until the end of the war 174th Tunnelling Compa served under Third Army.[3][7] It moved into the Houplines area in northern France, where it was in action in the Rue du Bois sector by early 1915.[1] By autumn 1915, the 181st Tunnelling Company had also moved to this area.[1]

The Somme 1915/16

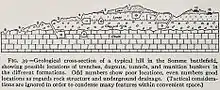

In July 1915, 174th Tunnelling Company moved to the Somme, where it took over French mine workings between La Boisselle and Carnoy,[1] some 27 miles (43 km) northeast of Amiens. On 24 July 1915, the unit established headquarters at Bray, taking over some 66 shafts at Carnoy, Fricourt, Maricourt and La Boisselle.[8] Around La Boisselle, the Germans had dug defensive transversal tunnels at a depth of about 80 feet (24 metres), parallel to the front line.[8] The British extended and deepened the tunnel system, first to 24 metres (79 ft) and ultimately 30 metres (98 ft). Above ground the infantry occupied trenches were just 45 metres (148 ft) apart.[9] Early attempts at mining by the British on the Western Front had commenced in late 1914 in the soft clay and sandy soils of Flanders. Mining at La Boisselle was in chalk, much harder and requiring different techniques.[8] The German advance had been halted at La Boisselle by French troops on 28 September 1914. There was bitter fighting for possession of the village cemetery, and for farm buildings on the south-western edge of the village, known as "L'îlot de La Boisselle" to the French, as "Granathof" (German: "shell farm") to the Germans and as "Glory Hole" to the British. In December 1914, French engineers began tunnelling beneath the ruins. With the war on the surface at stalemate, both sides continued to probe beneath the opponent's trenches and detonate ever-greater explosive charges. By August 1915, the French and Germans were working at a depth of 12 metres (39 ft); the size of their charges had reached 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb).[9] 174th Tunnelling Company was supported in its role on the Somme by the 183rd Tunnelling Company, but the British did not have enough miners to take over the large number of French shafts and the French agreed to leave their engineers at work for several weeks. To provide the tunnellers needed, the British formed the 178th and 179th Tunnelling Companies in August 1915, followed by the 185th and 252nd Tunnelling Companies in October.[10] The 181st Tunnelling Company was also present on the Somme.[5]

In October 1915, 174th Tunnelling Company was joined at La Boisselle by 179th Tunnelling Company, which had been formed in Third Army area that month.[1] Later that month, 174th Tunnelling Company gave up part of that front sector to the newly-formed 183rd Tunnelling Company, and concentrated on the Mametz sector instead.[1] As Allied preparations were under way for the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916), the British tunnelling companies were to make two major contributions by placing 19 large and small mines beneath the German positions along the front line and by preparing a series of shallow Russian saps from the British front line into no man's land, which would be opened at zero hour and allow the infantry to attack the German positions from a comparatively short distance.[11] In the front sector between Fricourt and Mametz,[12] 174th Tunnelling Company planted the Mametz West group of four 230-kilogram (500 lb) mines along the German trench lines running east from the heights of Bois Français, located south of Hidden Wood[13] and 1.03 kilometres (0.64 mi) south-east of Fricourt.[14] Local underground fighting at Bois Français had already taken place in the winter of 1914 and spring of 1915.[10] Before the summer of 1916, no-man's land south of Bois Français had already witnessed the blowing of at least eight mines, and the area of Kiel and Danube trenches, located some 0.46 kilometres (500 yd) to the east of Bois Français, had also seen extensive underground operations.[14] In October 1915, John Norton-Griffiths had even advocated the use of poison gas to deal with the German resistance in the Bois Français sector, but the proposal was not followed up. As at Fricourt, no frontal assault was planned in this area for 1 July as the British infantry would have to advance across large crater fields.[15] Instead, the Royal Engineers placed the Mametz West group of mines there – three charges at Kiel Trench and one at Danube Trench. The first purpose of these mines was to protect the left of the 7th Division's attack south of Mametz, while the second was to protect the 20th Battalion, Manchester Regiment during their attack on the German lines.[14]

By October 1916, 174th Tunnelling Company had moved north of the river Ancre, facing Beaumont-Hamel.[1]

Arras, 1917

During the fighting at Bullecourt on 11 April, men of 174th Tunnelling Company, under the command of Major Hutchinson, MC, worked continuously for 30 hours to dig out the victims of a collapsed house. They rescued nine men of the 2/6th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment alive.[16]

Spring Offensive 1918

In the German attack of March 1918, the unit suffered severe casualties while working on machine-gun emplacements at Bullecourt in northern France and fought as emergency infantry.[1] Soon after, 174th Tunnelling Company worked on a long section of trench in northern France near Monchy-au-Bois.[1]

See also

References

- The Tunnelling Companies RE Archived May 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, access date 25 April 2015

- "Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths (1871–1930)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Watson & Rinaldi, p. 49.

- Peter Barton/Peter Doyle/Johan Vandewalle, Beneath Flanders Fields - The Tunnellers' War 1914-1918, Staplehurst (Spellmount) (978-1862272378) p. 165.

- "Corps History – Part 14: The Corps and the First World War (1914–18)". Royal Engineers Museum. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Anthony Byledbal, "New Zealand Tunnelling Company: Chronology" (online Archived July 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine), access date 5 July 2015

- Watson & Rinaldi, p. 20.

- http://www.lochnagarcrater.org, Military Mining (online Archived 2015-06-29 at the Wayback Machine), accessed 25 June 2015

- La Boisselle Study Group, History (online), accessed 25 June 2015

- Jones 2010, p. 114.

- Jones 2010, p. 115.

- "Battle of the Somme: "Z" Day 1 July 1916". The Great War 1914-1918. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- Edmonds 1932, p. 349.

- Stedman 2011, p. 42.

- Jones 2010, p. 130.

- Laurie Magnus, The West Riding Territorials in the Great War, London: Keegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1920//Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-77-7, pp. 131–2.

Bibliography

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Stedman, M. (2011) [1997]. Somme: Fricourt–Mametz. Battleground Europe. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-574-8.

Further reading

- An overview of the history of 174th Tunnelling Company is also available in Robert K. Johns, Battle Beneath the Trenches: The Cornish Miners of 251 Tunnelling Company RE, Pen & Sword Military 2015 (ISBN 978-1473827004), p. 217 see online

- Alexander Barrie (1988). War Underground – The Tunnellers of the Great War. ISBN 1-871085-00-4.

- The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War 1914 -1919, – MILITARY MINING.

- Arthur Stockwin (ed.), Thirty-odd Feet Below Belgium: An Affair of Letters in the Great War 1915-1916, Parapress (2005), ISBN 978-1-89859-480-2 (online).

- Graham E. Watson & Richard A. Rinaldi, The Corps of Royal Engineers: Organization and Units 1889–2018, Tiger Lily Books, 2018, ISBN 978-171790180-4.