1794 Treason Trials

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall. In a repudiation of the government's policies, they were acquitted by three separate juries in November 1794 to public rejoicing. The treason trials were an extension of the sedition trials of 1792 and 1793 against parliamentary reformers in both England and Scotland.

Historical context

The historical backdrop to the Treason Trials is complex; it involves not only the British parliamentary reform efforts of the 1770s and 1780s but also the French Revolution. In the 1770s and 1780s, there was an effort among liberal-minded Members of Parliament to reform the British electoral system. A disproportionately small number of electors voted for MPs and many seats were bought. Christopher Wyvill and William Pitt the Younger argued for additional seats to be added to the House of Commons and the Duke of Richmond and John Cartwright advocated a more radical reform: "the payment of MPs, an end to corruption and patronage in parliamentary elections, annual parliaments (partly to enable the speedy removal of corrupt MPs) and, preeminently and most controversially, universal manhood suffrage".[1] Both efforts failed and the reform movement appeared moribund in the mid-1780s.

Once the revolution in France began to demonstrate the power of popular agitation, the British reform movement was reinvigorated. Much of the vigorous political debate in the 1790s in Britain was sparked by the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790). Surprising his friends and enemies alike, Burke, who had supported the American Revolution, criticized the French Revolution and the British radicals who had welcomed its early stages. While the radicals saw the revolution as analogous to Britain's own Glorious Revolution in 1688, which had restricted the powers of the monarchy, Burke argued that the appropriate historical analogy was the English Civil War (1642–1651) in which Charles I had been executed in 1649. He viewed the French Revolution as the violent overthrow of a legitimate government. In Reflections he argues that citizens do not have the right to revolt against their government, because civilizations, including governments, are the result of social and political consensus. If a culture's traditions were challenged, the result would be endless anarchy. There was an immediate response from the British supporters of the French revolution, most notably Mary Wollstonecraft in her Vindication of the Rights of Men and Thomas Paine in his Rights of Man. In this lively pamphlet war, now referred to as the "Revolution Controversy", British political commentators addressed topics ranging from representative government to human rights to the separation of church and state.[2]

1792 was the "annus mirabilis of eighteenth-century radicalism": its most important texts, such as Rights of Man, were published and the influence of the radical associations was at its height. In fact, it was as a result of the publication of the Rights of Man that such associations began to proliferate.[3] The most significant groups, made up of artisans, merchants and others from the middling and lower sorts, were the Sheffield Society for Constitutional Information, the London Corresponding Society (LCS) and the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI).[4] But it was not until these groups formed an alliance with the more genteel Society of the Friends of the People that the government became concerned. When this sympathy became known, the government issued a royal proclamation against seditious writings on 21 May 1792. In a dramatic increase compared to the rest of the century, there were over 100 prosecutions for sedition in the 1790s alone.[5] The British government, fearing an uprising similar to the French Revolution, took even more drastic steps to quash the radicals. They made an increasing number of political arrests and infiltrated the radical groups; they threatened to "revoke the licences of publicans who continued to host politicized debating societies and to carry reformist literature"; they seized the mail of "suspected dissidents"; and they supported groups that disrupted radical events and attacked radicals in the press.[6] Additionally, the British Government initiated the Aliens Act of 1793 in order to regulate the entrance of immigrants into Great Britain. Essentially, the Aliens Act enforced that aliens be recorded upon arrival and register with the local justice of the peace. Specifically, immigrants were required to give their names, ranks, occupations, and addresses.[7] Overall, the Aliens Act reduced the number of immigrants into Great Britain out of fear that one of them may be an unwanted spy. Radicals saw this period as "the institution of a system of terror, almost as hideous in its features, almost as gigantic in its stature, and infinitely more pernicious in its tendency, than France ever knew".[8]

Prelude: Trials of Thomas Paine, John Frost and Daniel Isaac Eaton

Thomas Paine

The administration did not immediately begin to prosecute all of its detractors after the proclamation against seditious writings was issued. Although Paine's publisher, J. S. Jordan, was indicted for sedition for publishing the Rights of Man in May 1792, Paine himself was not charged until the royal proclamation was promulgated. Even then, the government did not actively pursue him, apart from spying on him and continuing its propaganda campaign against "Mad Tom". Paine's trial was delayed until December and he fled to France in the intervening months, apparently with the government's blessing, which was more interested in getting rid of such a troublesome citizen than trying him in person. Moreover, afraid that Paine might use his trial as a political platform, the government may not have wanted to prosecute Paine personally.[9]

When the trial took place on 18 December 1792, its outcome was a foregone conclusion. The government, under Pitt's direction, had been lambasting Paine in the papers for months and the trial judge had negotiated the prosecution's arguments with them ahead of time. The radical Thomas Erskine defended Paine by arguing that his pamphlet was part of an honorable English tradition of political philosophy that included the writings of John Milton, John Locke and David Hume; he also pointed out that Paine was responding to the philosophical work of an MP, Burke. The Attorney-General argued that the pamphlet was aimed at readers "whose minds cannot be supposed to be conversant with subjects of this sort" and cited its cheap price as evidence of its lack of serious intent.[10] The prosecution did not even have to rebut Erskine's arguments; the jury informed the judge they had already decided Paine was guilty.[11]

John Frost

John Frost was a member of the SCI, a former associate of Pitt, an attorney and a friend of Paine's. On 6 November 1792 he got involved in a dispute with a friend over the French revolution in a tavern and was heard to say "Equality, and No King". This dispute was reported by publicans to government informers. When Frost went to Paris later that month, the government declared him an outlaw and encouraged him to stay in France. Frost, challenging the government to act, returned and surrendered himself to the authorities. Suggestions began to float around, from government and radical sources alike, that the government was embarrassed to prosecute Frost because of his former friendship with Pitt. But on 27 May, he was brought to trial for sedition. Erskine defended Frost, arguing that there was no seditious intent to his statement, his client was drunk, he was in a heated argument, and he was in a private space (the tavern). The Attorney-General contended that Frost "was a man whose seditious intent was carried with him wherever he went".[12] The jury convicted him.

Daniel Isaac Eaton

Daniel Isaac Eaton, the publisher of the popular periodical Politics for the People, was arrested on 7 December 1793 for publishing a statement by John Thelwall, a radical lecturer and debater. Thelwall had made a speech that included an anecdote about a tyrannical gamecock named "King Chanticleer" who was beheaded for its despotism and Eaton reprinted it. Eaton was imprisoned for three months before his trial in an effort to bankrupt him and his family. In February 1794, he was brought to trial and defended by John Gurney. Gurney argued that the comment was an indictment of tyranny in general or of Louis XVI, the king of France, and announced his dismay that anyone could think that the author meant George III. "Gurney went so far as to cheekily suggest that it was the Attorney-General who was guilty of seditious libel; by supplying those innuendos he, not Eaton or Thelwall, had represented George III as a tyrant."[13] Everyone laughed uproariously and Eaton was acquitted; the membership of the radical societies rocketed.

Treason Trials of 1794

The radical societies were briefly enjoying an upsurge in membership and influence. In the summer of 1793 several of them decided to convene in Edinburgh to decide on how to summon "a great Body of the People" to convince Parliament to reform, since it did not seem willing to reform itself. The government viewed this assembly as an attempt to set up an anti-parliament. In Scotland, three leaders of the convention were tried for sedition and sentenced to fourteen years of service in Botany Bay. Such harsh sentences shocked the nation and while initially the societies believed that an insurrection might be necessary to resist such an overbearing government, their rhetoric never materialized into an actual armed rebellion.[14] Plans were made by some of the societies to meet again if the government became more hostile (e.g. if they suspended habeas corpus). In 1794, a plan was circulated to convene again, but it never got off the ground. The government, frightened however, arrested six members of the SCI and 13 members of the LCS on suspicion of "treasonable practices" in conspiring to assume "a pretended general convention of the people, in contempt and defiance of the authority of parliament, and on principles subversive of the existing laws and constitution, and directly tending to the introduction of that system of anarchy and confusion which has fatally prevailed in France".[15] Over thirty men were arrested in all. Of the people arrested were Thomas Hardy, secretary of the LCS; the linguist John Horne Tooke; the novelist and dramatist Thomas Holcroft (arrested in October); the Unitarian minister Jeremiah Joyce; writer and lecturer John Thelwall; bookseller and pamphleteer Thomas Spence; and silversmith and, later, historian John Baxter.[16]

After the arrests, the government formed two secret committees to study the papers they had seized from the radicals' houses. After the first committee report, the government introduced a bill in the House of Commons to suspend habeas corpus; thus, those arrested on suspicion of treason could be held without bail or charge until February 1795. In June 1794 the committee issued a second report, asserting that the radical societies had been planning at least to "over-awe" the sovereign and Parliament by the show of "a great Body of the People" if not to overthrow the government and install a French-style republic. They claimed that the societies had attempted to assemble a large armoury for this purpose, but no evidence could be found for it.[17] They were charged with an assortment of crimes, but seditious libel and treason were the most serious. The government propagated the notion that the radicals had committed a new kind of treason, what they called "modern" or "French" treason. While previous defendants had tried to replace one king with another from another dynasty, these democrats wanted to overthrow the entire monarchical system and remove the king entirely. "Modern French treason, it seemed, was different from, was worse than, old-fashioned English treason."[18] The treason statute, that of the Act of Edward III from 1351, did not apply well to this new kind of treason. The Attorney-General Sir John Scott, who would prosecute Hardy and Horne Tooke, "decided to base the indictment on the charge that the societies had been engaged in a conspiracy to levy war against the king, that they intended to subvert the constitution, to depose the King, and put him to death; and for that purpose, and 'with Force and Arms', they conspired to excite insurrection and rebellion" (emphasis in original).[18]

Initially the men were confined to the Tower of London, but they were moved to Newgate prison. Those charged with treason faced the brutal punishment of hanging, drawing and quartering if convicted: each would have been "hanged by the neck, cut down while still alive, disembowelled (and his entrails burned before his face) and then beheaded and quartered".[19] The entire radical movement was also on trial; there were supposedly 800 warrants that were ready to be acted upon when the government won its case.[20]

Thomas Hardy

Hardy's trial was first; his wife had died while he was in prison, generating support for him among the populace.[21] Thomas Erskine, defending again, argued that the radicals had proposed nothing more than the Duke of Richmond (now an anti-reformer) had in the 1780s and "their plan for a convention of delegates was borrowed from a similar plan advanced by Pitt himself".[22] The government could provide no real evidence of an armed insurrection. The Attorney-General's opening statement lasted nine hours, leading the former Lord Chancellor Lord Thurlow to comment that "there was no treason".[23] Treason must be "clear and obvious"; the great legal theorist Edward Coke had argued that treason was to be determined "not upon conjecturall [sic] presumptions, or inferences, or strains of wit, but upon good and sufficient proof".[23] Part of Erskine's effective defence was to dismiss the prosecution's case, as it was based on "strains of wit" or "imagination" (a play on words of the statute itself).[24] He claimed, as he had in the earlier trials, that it was the prosecution that was "imagining the king's death" rather than the defence. His cross-examination of the prosecution's spies also helped demolish their case; he "cross-examined these witnesses in a tone of contemptuous disbelief and managed to discredit much of their evidence".[25] After a nine-day trial, which was exceptionally long for the time, he was acquitted.[26] The foreman of the jury fainted after delivering his verdict of not guilty, and the crowd enthusiastically carried Hardy through the streets of London.[19]

In his speeches, Erskine emphasized that the radical organizations, primarily the London Corresponding Society and the Society for Constitutional Information, were dedicated to a revolution of ideas, not a violent revolution—they embodied the new ideals of the Enlightenment.[27] Erskine was helped in his defence by pamphlets such as William Godwin's Cursory Strictures on the Charge Delivered by Lord Chief Justice Eyre to the Grand Jury, 2 October 1794.[28]

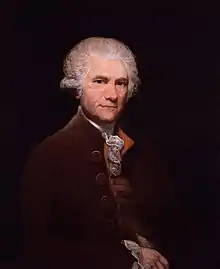

John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke's trial followed Hardy's, in which Pitt was forced to testify and admit that he had attended radical meetings himself.[29] Throughout the trial Horne Tooke "combined the affectation of boredom with irreverent wit".[21] One observer noted that when asked by the court if he would be tried "by God and his Country", he "eyed the court for some seconds with an air of significancy few men are so well able to assume, and shaking his head, emphatically answered 'I would be tried by God and my country, but—!'"[30] After a long trial, he too was acquitted.[26]

Horne Took used to remark later that he owed his life to Godwin’s Cursory Strictures, which had been published anonymously in newspapers and pamphlets, leading to legal arguments that took up more than an hour of the first day’s proceedings[31]

All of the other members of the SCI were released after these two trials, as it became obvious to the government that they would not gain any convictions.[26]

John Thelwall

John Thelwall was tried last; the government felt forced to try him because the loyalist press had argued that his case was particularly strong.[26] While awaiting trial, he wrote and published poetry indicting the entire process.[29] During Thelwall's trial, various members of the London Corresponding Society testified that Thelwall and the others had no concrete plans to overthrow the government, and that details of how reform was to be achieved were an "afterthought". This undermined the prosecution's claims that the society was responsible for fomenting rebellion.[32] Thelwall was also acquitted, after which the rest of the cases were dismissed.[33]

Trial literature

All of these trials, both those from 1792 and those from 1794, were published as part of an 18th-century genre called "trial literature". Often, multiple versions of famous trials would be published and since the shorthand takers were not always precise, the accounts disagree. Moreover, the accounts were sometimes altered by one side or another. Importantly, those in the courtroom knew that their words would be published. In Scotland, one of the accused ringleaders of the plot said: "What I say this day will not be confined within these walls, but will spread far and wide."[34] Indeed, the government may have resisted trying Paine until he had left the country because of the notorious power of his pen.[35]

Aftermath

_by_James_Gillray.jpg.webp)

Although all of the defendants of the Treason Trials had been acquitted, the administration and the loyalists assumed they were guilty. Secretary at War William Windham referred to the radicals as "acquitted felon[s]" and William Pitt and the Attorney-General called them "morally guilty".[36] There was widespread agreement that they got off because the treason statute was outdated. When, in October 1795, crowds threw refuse at the king and insulted him, demanding a cessation of the war with France and lower bread prices, Parliament passed the "gagging acts" (the Seditious Meetings Act and the Treasonable Practices Act, also known as the "Two Acts"). Under these new laws, it was almost impossible to have a public meeting and speech at such meetings was severely curtailed.[37] As a result of these legislative acts, societies that were not directly involved with the Treason Trials, like the Society of the Friends of the People, disbanded.[38] British "radicalism encountered a severe set-back" during these years, and it was not until a generation later that any real reform could be enacted.[39] The trials, although they were not government victories, served the purpose for which they were intended—all of these men, except Thelwall, withdrew from active radical politics as did many others fearful of governmental retribution. Few took their place.[40]

Notes

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", x.

- Butler, "Introductory Essay"; Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xi–xii.

- Butler, "Introductory essay," 7; see also Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xiii.

- Keen, 54.

- "The 1905 Aliens Act | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Qtd. in Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxi.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xviii.

- Qtd. in Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xix.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xix.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xx.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xx–xxii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxiv–xxv.

- Qtd. in Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxvii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxvii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxviii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxi.

- Thompson, 19.

- Thompson, 137.

- Thompson, 135.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxi–xxxii.

- Qtd. in Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxiv; Thompson, 135.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxiv.

- Keen 164–165.

- Butler, "Introductory essay", 198–199.

- Thompson, 136.

- Qtd. in Thompson, 135.

- St Clair, William (1990). The Godwins and the Shelleys. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 130–132. ISBN 0-571-14417-9.

- Jones, Rhian (2013). "Talking Treason? John Thelwall and the Privy Council Examinations of the English Jacobins, 1794" (PDF). Thelwall Studies. John Thelwall Society.

- Thompson, 19; Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxiv.

- Qtd. in Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxviii.

- Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxviii.

- Qtd. in Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxv.

- Butler, Romantics, 49; Thompson, 19; Barrell and Mee, "Introduction", xxxv; Keen, 54.

- Iain Hampsher-Monk. "Civic Humanism and Parliamentary Reform: The Case of the Society of the Friends of the People." (Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 70–89). Journal of British Studies, 1979. JSTOR 175513. 24 November 2015. (subscription required)

- Butler, "Introductory essay," 3.

- Thompson, 137–8.

Bibliography

- Barrell, John and Jon Mee, eds. "Introduction." Trials for Treason and Sedition, 1792–1794. 8 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 2006–7. ISBN 9781851967322.

- Barrell, John. Imagining the King's Death: Figurative Treason, Fantasies of Regicide 1793–1796. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Beattie. J. M. Crime and the Courts in England 1660–1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Butler, Marilyn, ed. "Introductory essay." Burke, Paine, Godwin, and the Revolution Controversy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-521-28656-5.

- Butler, Marilyn. Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-19-289132-4.

- Emsley, Clive. "An Aspect of Pitt's 'Terror': Prosecutions for Sedition during the 1790s." Social History (1981): 155084.

- Epstein, James. "'Equality and No King': Sociability and Sedition: the Case of John Frost". Romantic Sociability: Social Networks and Literary Culture in Britain 1770–1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Goodwin, Albert. The Friends of Liberty: The English Democratic Movement in the Age of the French Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- Green, Thomas Andrew. "The Jury, Seditious Libel, and the Criminal Law." Verdict According to Conscience: Perspectives on the English Criminal Trial Jury 1200–1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Hostettler, John. Thomas Erskine and Trial by Jury. 2010. Waterside Press.

- Keen, Paul. The Crisis of Literature in the 1790s: Print Culture and the Public Sphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-65325-8.

- King, Peter. Crime, Justice and Discretion in England, 1740–1820. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Landau, Norma. Law, Crime and English Society, 1660–1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Langbein, John. The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Lobban, Michael. "From Seditious Libel to Unlawful Assembly: Peterloo and the Changing Face of Political Crime c. 1770–1820." Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 10 (1990): 307–52.

- Lobban, Michael. "Treason, Sedition and the Radical Movement in the Age of the French Revolution." Liverpool Law Review 22 (2000): 205–34.

- Pascoe, Judith. "The Courtroom Theatre of the 1794 Treason Trials." Romantic Theatricality: Gender, Poetry, and Spectatorship. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

- Steffen, Lisa. Defining a British State: Treason and National Identity, 1608–1820. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001.

- Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books, 1966. ISBN 0-394-70322-7.

- Wharam, Alan. The Treason Trials, 1794. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992.

External links

- Eighteenth-century chronology from 1794 Archived 10 January 2000 at the Wayback Machine

- The Trial of John Horne Tooke for High Treason (1795) full-text at google books

- The Trial of Thomas Hardy for High Treason (1796) full-text at google books