1804 dollar

The 1804 dollar or Bowed Liberty Dollar was a dollar coin struck by the United States Mint, of which fifteen specimens are currently known to exist. Though dated 1804, none were struck in that year; all were minted in the 1830s or later. They were first created for use in special proof coin sets used as diplomatic gifts during Edmund Roberts' trips to Siam and Muscat.

United States | |

| Value | 1 U.S. dollar |

|---|---|

| Mass | Class I: 410.21 grains (26.581 g)–416.4 grains (26.98 g)[1] Class II: 392.6 grains (25.45 g)[2] Class III: 402.8 grains (26.10 g)–416.25 grains (26.973 g)[3] |

| Diameter | 37-40 mm (1.49-1.57 in) |

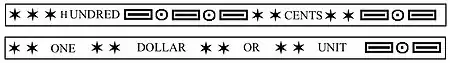

| Edge | Class I: HUNDRED CENTS ONE DOLLAR OR UNIT Class II: Plain - HUNDRED CENTS ONE DOLLAR OR UNIT Class III: HUNDRED CENTS ONE DOLLAR OR UNIT |

| Composition | 90.0% Ag 10.0% Cu |

| Obverse | |

| |

| The obverse of a Class I 1804 dollar | |

| Design | Bust of Liberty, facing to the viewer's right, with the date and the word "LIBERTY" |

| Design date | 1795 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| The reverse of a Class I 1804 dollar | |

| Design | Heraldic representation of an eagle holding a scroll reading "E PLURIBUS UNUM", above which are 13 stars and clouds, with "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA" along the periphery |

| Design date | 1798 |

Edmund Roberts distributed the coins in 1834 and 1835. Two additional sets were ordered for government officials in Japan and Cochinchina, but Roberts died in Macau before they could be delivered. Besides those 1804 dollars produced for inclusion in the diplomatic sets, the Mint struck some examples which were used to trade with collectors for pieces desired for the Mint's coin cabinet. Numismatists first became aware of the 1804 dollar in 1842, when an illustration of one example appeared in a publication authored by two Mint employees. A collector subsequently acquired one example from the Mint in 1843. In response to numismatic demand, several examples were surreptitiously produced by Mint officials. Unlike the original coins, these later restrikes lacked the correct edge lettering, although later examples released from the Mint bore the correct lettering. The coins produced for the diplomatic mission, those struck surreptitiously without edge lettering and those with lettering are known collectively as "Class I", "Class II" and "Class III" dollars, respectively.

From their discovery by numismatists, 1804 dollars have commanded high prices. Auction prices reached $1,000 by 1885, and in the mid-twentieth century, the coins realized over $30,000. In 1999, a Class I example sold for $4.14 million, then the highest price paid for any coin. Their high value has caused 1804 dollars to be a frequent target of counterfeiting and other methods of deception.

Background

The Coinage Act of 1792, the legislation which provided for the establishment of the Mint of the United States (today the United States Mint), authorized coinage of multiple denominations of gold, silver and copper coins.[4] According to the act, the dollar, or "unit", was to "be of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver".[4] The act went on to state that the coin would be struck in an alloy consisting of 89.2 percent silver and 10.8 percent copper.[5] The purity and weight standards outlined in the Act were based on the mean of several assays conducted on Spanish milled dollars.[6] However, the dollars were mandated by Spanish law to contain 90.2 percent silver, and most of the unworn examples in circulation in the United States at the time contained approximately 1.75 grains (0.113 g) more than the silver dollars authorized by the Act.[7] In 1793, President George Washington signed into law a bill which declared Spanish milled dollars legal tender, provided that they weighed no less than 415 grains (26.9 g), which meant that at the lowest weight allowed by law, the Spanish dollars would contain approximately 0.5 percent less silver than the United States dollar coins.[8][9] As a result, the United States silver dollars and unworn Spanish dollars were largely forced out of circulation in accordance with Gresham's law; the lighter Spanish dollars were shipped in quantity for circulation in the United States, while the heavier pieces would be turned in to the Philadelphia Mint to be recoined into United States coinage to take advantage of the discrepancy in weight.[9] At that time, silver bullion was supplied to the Mint exclusively by private depositors, who, according to the Coinage Act of 1792, had the right to have their bullion coined free of charge.[10][5] As large silver coins were a preferred method of commerce throughout the world, especially China, a considerable number of the United States dollars requested by silver depositors were exported to satisfy that demand.[9]

The first dollar coins, known as Flowing Hair dollars, were issued by the Mint beginning in 1794. By 1800, a majority of depositors requested their bullion be struck as silver dollars, which were then utilizing the Draped Bust design.[11] This contributed to a shortage of small change in circulation, and as a result, the public became increasingly critical of the Mint.[12] Mint Director Elias Boudinot began encouraging depositors to accept fractional coins, and the production of dollars began to decrease in relation to the smaller coins.[13] Dollar coin production ceased in March 1804, although those pieces bore the date of 1803.[12][lower-alpha 1] In his 1805 report, Mint Director Robert Patterson stated that "[t]he striking of small coins is a measure which has been adopted to accommodate the banks and other depositors, and at their particular request, both with a view of furnishing a supply of small change, and to prevent the exportation of the specie of the United States to foreign countries."[15] Though none had been struck for over two years, Secretary of State James Madison officially suspended silver dollar coinage on May 1, 1806, addressing a letter to Patterson:

Sir: In Consequence of a representation from the director of the Bank of the United States that considerable purchases have been made of dollars coined at the mint for the purpose of exporting them, and as it is probable further purchases and exportations will be made the President directs that all the silver to be coined at the mint shall be of small denominations, so that the value of the largest pieces shall not exceed half a dollar.[16]

Production

Edmund Roberts' diplomatic mission

In 1832, commercial shipper Edmund Roberts began acting as an envoy to Asia on behalf of the United States government, with the intent of negotiating trade deals in the region.[17][lower-alpha 2] During his mission, he reached deals both with Said bin Sultan, the Sultan of Muscat and Oman, and the Phra Khlang of Siam (modern Thailand), an important financial minister of that nation.[19] Roberts was given items which were to be presented as gifts to the officials with whom he was negotiating, but described them as being of "very mean quality, and of inconsiderable value".[20] After the treaties were ratified in the United States, Roberts had to return to Siam and Muscat to receive approval from the representatives of those nations.[19] In a letter to the Department of State dated October 8, 1834, Roberts decried the gifts of his previous journey as inadequate and insulting to his hosts in the Orient.[19] In addition to several other items, he requested a set of coins as an appropriate offering to Said bin Sultan:

I am rather at a loss to know what articles will be most acceptable to the Sultan, but I suppose a complete set of new gold & silver & copper coins of the U.S. neatly arranged in a morocco case & then to have an outward covering would be proper to send not only to the sultan, but to other Asiatics.[21]

In a November 11, 1834 letter sent to Mint Director Samuel Moore, Secretary of State John Forsyth approved Roberts' suggestion, writing:

The President [Andrew Jackson] has directed that a complete set of the coins of the United States be sent to the King of Siam, and another to the Sultan of Muscat. You are requested, therefore, to forward to the Department for that purpose, duplicate specimens of each kind now in use, whether of gold, silver, or copper.[21]

He also directed Moore to have two Morocco leather boxes made to house the coins. He stated that one should be yellow in color, and the other crimson, and that funds could be drawn from the Treasury for the value of the boxes and coins.[21] Later, in a letter dated December 2, 1834, Forsyth directed Moore to include "national emblems" (including an eagle and stars) on the exterior of the cases.[21]

In their book The Fantastic 1804 Dollar, numismatic historians Eric P. Newman and Kenneth E. Bressett assert that a problem arose at the Mint as to how to interpret Forsyth's order.[22] As his initial correspondence indicated that the sets were to include coins of every type then in use, Mint officials included both the silver dollar and gold eagle.[lower-alpha 3] The moratorium on silver dollar coinage had been lifted in 1831, but none had been coined since those issued in March 1804.[24] Two sets of coins, minted in proof finish, were completed and delivered along with their boxes to Roberts shortly prior to his departure on the USS Peacock on April 27, 1835.[25] The dollars included the sets bore the Draped Bust design, depicting an allegorical representation of Liberty on the obverse and a heraldic eagle on the reverse.[26] A list of diplomatic gifts was also proposed for missions to Japan and Cochin-China (today part of Vietnam), which included two additional sets of coins.[27]

Roberts delivered the first set of coins to Said bin Sultan on October 1, 1835.[28] He delivered the next set to King Rama III of Siam the following year, on April 6.[29] Roberts died in Macau on June 12, 1836, before he could initiate contact with any other nations. On June 30, Edmund P. Kennedy, commodore of the diplomatic fleet, wrote to the State Department that he had "directed that the presents [which remained ungifted due to Roberts’ death] be forwarded to the United States".[27] The proof sets meant for Cochin-China and Japan were likely included in the shipment of returned presents.[27] All dollars struck for inclusion in the diplomatic gift sets were likely dated 1804.[30] It is unknown why that date was chosen for the dollars, but numismatic historian R.W. Julian suggests that it could have been done to prevent angering collectors who would not have been able to acquire the 1834-dated coin for their collections; Chief Coiner Adam Eckfeldt, after consulting with Moore, mistakenly determined that 19,570 dollars bearing the date 1804 were struck in that year.[31][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] The dollars minted for the diplomatic gift sets, as well as other examples struck with the same dies, are collectively known as "Class I" 1804 dollars.[34] In total, eight specimens of this type are known today.[35]

Later restrikes

.jpg.webp)

During the nineteenth century, Mint employees produced unauthorized copies of medals and coins, sometimes backdated.[36] Although coin restrikes were created openly at the Philadelphia Mint from the 1830s, the practice became clandestine by the end of the 1850s.[37] In the decades after the first 1804 dollars were produced, collectors became aware of their existence and desired to obtain them.[38] Several were struck at the Mint in 1858.[39] Those coins, which became known as "Class II" 1804 dollars, had plain, unlettered edges, as opposed to standard issue Draped Bust dollars and those struck as diplomatic gifts, all of which had edge lettering applied by the Castaing machine.[39] In 1859, James Ross Snowden unsuccessfully requested permission from the Treasury Secretary to create patterns and restrikes of rare coins for sale to collectors, and in that year, dealers began offering plain edge 1804 dollars to the public.[39] At least three were offered for sale by various dealers in 1859, and coin dealer Ebenezer Locke Mason claimed that he was offered three by Theodore Eckfeldt, a Mint employee and nephew of Adam Eckfeldt (who had died in 1852).[40] After the public became aware that Mint officials had permitted restrikes, there was a minor scandal which resulted in a Congressional investigation and the destruction of outdated coinage dies. The controversy prompted William E. DuBois, Mint Assayer, to try, in 1860, to recall the examples of the 1804 dollar in private hands.[41][39] According to DuBois, five coins were known to be privately owned, of which four were recovered.[39] He stated that three were destroyed in his presence, and one was added to the Mint's coin cabinet (of which he was curator, and which is today the National Numismatic Collection), where it remains today.[42] The coin, which is the sole known Class II specimen in existence, was struck over an 1857 Swiss shooting thaler minted for the federal shooting festival held in Bern.[36] The fifth coin, alluded to by DuBois, is not currently accounted for, although its edge may have been lettered after its recovery in an attempt to pass it as an original.[43] Coins with added lettering are known as "Class III" 1804 dollars.[44] The obverse coinage die used to strike the Class II and Class III 1804 dollars was deposited in safekeeping in 1860, and the reverse die was destroyed in that year.[44] The obverse die was defaced in 1869.[45]

Class III dollars are identical to the Class II dollar, except lettering similar to that on the Class I dollars was applied to the edge of the coins.[34] Based on the slightly concave appearance of the Class III dollars, it is likely that all were given edge lettering at some point after striking; as the Castaing machine was meant to be used prior to striking, its improper use resulted in a deformation of the coin surface.[46] Newman and Bressett assert that they were struck at approximately the same time as the Class II dollars, and that the edges were lettered and the coins concealed by Mint employees until 1869, when one was offered to a coin collector, who rejected it as a restrike.[47] However, numismatist S. Hudson Chapman believed that some Class III dollars were struck as late as 1876.[48] In 1875, several were sold by Philadelphia coin dealer John W. Haseltine.[45] Six specimens of the Class III dollar are known today.[35]

Numismatic interest

Collectors first became aware of the existence of the 1804 dollar in 1842, when a pantograph reproduction of one specimen was featured in A Manual of Gold and Silver Coins of All Nations, a work authored by Mint employees Jacob R. Eckfeldt and William DuBois.[49][50] The first private collector to obtain an example was Matthew A. Stickney, who acquired the coin from the Mint on May 9, 1843, by trading certain rare coins from his collection, including a unique early United States Immune Columbia coin struck in gold.[51] Interest in coin collecting and the 1804 dollars began increasing, and by 1860, the dollars saw extensive coverage by numismatists.[52] In 1885, auctioneer W.E. Woodward described the 1804 dollar as "the king of coins", a moniker which it maintains today.[53] Numismatic historian Q. David Bowers asserts that the 1804 dollar has attracted more attention than any other coin.[54] All fifteen extant specimens are acknowledged and studied by numismatists. They are identified by nicknames based on prominent owners, or the first individuals known to have possessed the coins.[55]

At the 1962 American Numismatic Association convention, British numismatist David B. Spink announced that he was in possession of a theretofore unknown 1804 dollar specimen.[56] The coin was housed in a yellow leather case embossed with an eagle and other ornamentation, conforming to the description of that made for the King of Siam. The set consisted of a half cent, cent, dime, quarter, half dollar, dollar, quarter eagle, half eagle and eagle.[56][lower-alpha 6] As all of the coins in the set were dated 1834 with the exception of the dollar and eagle, it provided the first definitive proof that an 1804 dollar was included in the diplomatic presentation sets.[56] According to Spink, the set was offered to him by two women whom he believed were descendants of Anna Leonowens, tutor of the children of Rama IV (half-brother and heir of Rama III) and fictionalized protagonist of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I.[58]

Years of production

The fact that no 1804 dollars were struck in 1804 was not widely accepted by numismatists until the early twentieth century.[59] Before such time, the actual year in which they were struck remained contentious among numismatists. Early on, collectors assumed that the 1804 dollars were struck in 1804, and their rarity was explained by various theories. The bulk of the mintage was variously rumored to have been paid to Barbary pirates as ransom, lost at sea en route to China, and melted before leaving the Philadelphia Mint.[60] In 1867, numismatist W. Elliot Woodward acknowledged that 1804 dollars were struck as diplomatic gifts in 1834, but he also believed that others were struck in 1804.[61] Numismatists Lyman H. Low and William T. R. Marvin, writing for the American Journal of Numismatics in 1899, stated that "the journal confidently asserts that there is no dollar dated 1804 which was struck in that year by the U.S. Mint."[62] In 1891, numismatist John A. Nexsen wrote that the Class I 1804 dollars were "without doubt coined in 1804".[63] In 1905, he recanted his earlier assertions, stating that "no one now believes that they were coined in 1804."[64]

According to Newman and Bressett, the manner in which the 1804 dollars were produced is proof that none were struck in 1804.[65] They note that the Castaing machine's edging dies utilized an 'H' that was undersized in relation to the other letters, the same as those used on Draped Bust dollars throughout the regular production of those coins.[65] However, the edge lettering on all Class I 1804 dollars is deformed and partially obliterated, meaning that they were not struck in an open-collared coinage press as was used in 1804, but one which used a steel collar that was not introduced to the Mint until 1833.[65] The deformation of the edge lettering was caused by pressure pushing the coinage metal against the steel collar containing the coin blank.[65] Additionally, many 1804 dollars were struck in proof finish, a technique which was first employed at the Mint in 1817.[66]

Sale prices

From the time numismatists became aware of 1804 dollars, they have commanded high prices, both in relation to their face value and the numismatic value of other silver dollars.[67] Some early examples were maintained in the Mint's coin cabinet for use in trades, and in 1859, dealers began offering Class II dollars priced at $75, while Theodore Eckfeldt reportedly offered a Philadelphia coin dealer three coins for $70 each.[40] In 1883, a Class III dollar was reportedly purchased in Vienna for $740, and a Class I specimen was auctioned for $1,000 in 1885 by Henry and Samuel H. Chapman.[68][69] In 1903, an example sold for $1,800, and the same coin reportedly sold for $4,250 in 1941.[70] In 1960, a Class III dollar fetched $28,000 at an auction conducted by Stack's, a coin firm, and the same coin reached $36,000 at another Stack's sale in 1963.[71] A Class I specimen brought $77,500 at a 1970 Stack's auction, and during a 1980 rise in coin prices, a Class III example sold for $400,000 by Bowers and Ruddy Galleries.[72][73] A Class I example reached $990,000 at a Superior Galleries auction in 1990, and an example once owned by coin collector Louis Eliasberg became the first 1804 dollar to surpass $1 million at auction, selling for $1,815,000 at a sale conducted by Bowers and Merena, Inc., in 1997.[72]

The price reached an all-time high in 1999, when the finest known specimen, graded Proof-68 by the Professional Coin Grading Service, which is believed to have been the example presented to Said bin Sultan, was auctioned by Bowers and Merena for $4,140,000.[74] At the time of the sale, this was the highest price paid for any coin.[75] In 2008, a Class I example was sold by Heritage Auctions for $3,737,500, and a Class III was sold by the same firm for $2,300,000 in 2009.[72]

Counterfeits and reproductions

Counterfeits and spurious reproductions of the 1804 dollar have been created since numismatists became aware of the coins' high value.[76] James A. Bolen, a medallist and coin collector who created copies of valuable coins between 1862 and 1869, fabricated an 1804 dollar by altering the last digit in the date of a genuine 1803 example.[76] Although Bolen added his name to the edge of the coin, other forgers created altered date coins with the intent to deceive.[77] Nineteenth-century stage actor John T. Raymond purchased a specimen of the coin, which was later revealed to be a forgery, for $300.[78] All silver dollars dated between 1800 and 1803 were subject to alteration to 1804 dollars, but 1801 was the date most commonly used for that purpose.[79][80]

In addition to altered dates, electrotypes of the 1804 dollar were created, both for the purposes of study and fraud.[81][lower-alpha 7] One such coin in the collection of the San Francisco Mint was described by them as genuine from 1887 to 1927.[83] Electrotypes were also created by Mint employees, and one was used as the basis for the pantograph reproductions which appeared in Eckfeldt and DuBois' 1842 A Manual of Gold and Silver Coins of All Nations.[84]

More modern replicas, known as "Saigon copies", were commonly offered as original at low prices to American soldiers during the Vietnam War. In Saigon and other South Vietnamese cities, as well in nearby Thailand, military personnel were offered the copies by vendors who sometimes claimed that they were family heirlooms.[85][86] In 2012, Professional Coin Grading Service founder David Hall stated that counterfeit 1804 dollars had been available in Hong Kong for decades.[87]

Known specimens

| Type | Representative obverse | Representative reverse | Specimen nicknames[88] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I |  |

|

Mint Cabinet Specimen/U.S. Mint Specimen |

| Stickney Specimen | |||

| King of Siam Presentation Specimen/Siam Specimen | |||

| Sultan of Muscat Presentation Specimen/Watters Specimen | |||

| Dexter Specimen | |||

| Parmalee-Reed Specimen | |||

| Mickley Specimen | |||

| Cohen Specimen | |||

| Class II |  |

|

Mint Cabinet Specimen/U.S. Mint Specimen |

| Class III |  |

|

Berg Specimen |

| Adams Specimen | |||

| Davis Specimen | |||

| Linderman Specimen | |||

| Driefus–Rosenthal Specimen/Rosenthal Specimen | |||

| Idler Specimen |

See also

Notes

- In the early days of the Mint, dies were saved and reused as an economic measure. They were sometimes modified to include the current date, but that practice was not universally applied.[14]

- Officially, Roberts was a "special agent", but he was described in a later State Department document as a "Special Envoy". Numismatic historian Q. David Bowers suggests that Roberts' original title may have been chosen to avoid intervention from Congress, as official ambassadors and envoys required approval by the United States Senate.[18]

- Although the dollars struck in 1804 bore the date 1803, the eagles struck in that year were not antedated.[23] Mintage of that denomination ceased because the intrinsic bullion value became higher than the face value of the coin.[22]

- Moore consulted the Mint records, which indicated that 19,570 dollars were struck in 1804. However, those coins, struck from old dies as was common practice at the time, were dated 1803.[31]

- The issue of when dollar coin mintage actually ceased was further confused by a later misreading of Patterson's 1806 annual report to Congress, which erroneously suggested that 321 were coined in 1805.[32] In reality, the coins listed were struck earlier and included as part of a bullion deposit routed through the Mint.[33]

- There were two empty openings in the case: one the size of a half dime, and another the size of a quarter eagle.[56] The extra opening may have been used for a quarter eagle inscribed "E PLURIBUS UNUM", which was removed from that denomination in 1834;[57] The quarter eagle utilized for the set was an example which lacked the motto.

- Electrotypes were created by making a wax impression of both sides of the coin, coating the impressions with graphite, then submerging them in a plating solution. Copper in the solution was deposited into the impressions, creating reproduction of the obverse and reverse, which were then joined together.[82]

References

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 120–122.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 128.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 129–130.

- Act of April 2, 1792, p. 3.

- Act of April 2, 1792, p. 4.

- Breen, 1988, p. 423.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 20–21.

- Act of February 9, 1793, p. 7.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 21.

- Julian, 1993, p. 35.

- Julian, 1993, p. 44.

- Julian, 1993, p. 46.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 22.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 41.

- American State Papers, 1832, p. 165.

- Laws of the United States Relating to the Coinage, 1892, p. 16.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 142.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 191.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 63.

- Roberts, 1837, p. 319.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 195.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 64.

- Yeoman, 2008, p. 255.

- Julian, 1993, p. 432.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 64–65.

- Yeoman, 2008, p. 210.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 65.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 235.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 264.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 28.

- Julian, 1993, p. 433.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 17–18.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 18–19.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 35.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 203.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 75.

- Bowers, 1999, pp. 17–19.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 78.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 80.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 80–81.

- Frossard, 1891, p. 231.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 75–81.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 81.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 112.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 88.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 60–61.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 114.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 356.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 19.

- Eckfeldt & DuBois, 1842, Plate II.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 71–73.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 348.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 350.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 347.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 357.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 66.

- Yeoman, 2008, p. 247.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 359.

- Albanese, 2009, p. 111.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 24–25.

- Bowers, 1999, p. 351.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 94.

- Nexsen, 1891, p. 98.

- Nexsen, 1905, p. 102.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 58.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 61.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 13.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 129.

- American Journal of Numismatics, 1904, p. 92.

- McIlvaine, 1941, p. 29.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 194.

- Beety, 2013, p. 9.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 189.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 175–178.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 178.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 103.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 103–104.

- The Art Collector, 1891, p. 90.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 105.

- Alexander & Co., 1910, p. 8.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, pp. 106–107.

- Ruddy, 2005, p. 265.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 106.

- Newman & Bressett, 2009, p. 107.

- Rochette, 1997.

- Ganz, 2010, p. 99.

- Numismatic News, 2012.

- Bowers, 1999, pp. 357–369.

Bibliography

- Albanese, Dean (2009). King of Eagles: The Most Remarkable Coin Ever Produced by the U.S. Mint (First ed.). New York, New York: Harris Media. ISBN 978-0-9799475-2-0.

- Alexander & Co. (1910). Alexander & Co.'s Hub Coin Book (17th ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Alexander & Co.

- Beety, John Dale (2013). "The 1804 Dollar—An Introduction to the 'King of American Coins'". The Mickley–Hawn–Queller Class I Original 1804 Dollar, PR62 From the Greensboro Collection, Part IV (PDF) (PDF). Dallas, Texas: Heritage Numismatic Auctions.

- Bowers, Q. David (1999). The Rare Silver Dollars Dated 1804 and the Exciting Adventures of Edmund Roberts. Wolfeboro, New Hampshire: Bowers and Merena Galleries. ISBN 0-943161-82-7.

- Breen, Walter (1988). Walter Breen's Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. New York, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-14207-6.

- Eckfeldt, Jacob R.; DuBois, William E. (1842). A Manual of Gold and Silver Coins of All Nations, Struck Within the Past Century. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: C. Sherman.

- Frossard, Edouard (October 1, 1891). Alfred Trumble (ed.). "The U.S. Mint Collection". The Collector. New York, New York. II (19).

- Ganz, David L. (2010). Rare Coin Investing. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-4402-1358-8.

- Julian, R.W. (1993). Bowers, Q. David (ed.). Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States. Wolfeboro, New Hampshire: Bowers and Merena Galleries. ISBN 0-943161-48-7.

- Lowrie, Walter; Clarke, Matthew St. Clair, eds. (1832). American State Papers. Vol. VI. Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton.

- Marvin, William T.; Low, Lyman H., eds. (January 1904). "The 1804 Dollar Again". American Journal of Numismatics. Boston, Massachusetts. XXXVIII (3).

- McIlvaine, Arthur D. (1941). The Silver Dollars of the United States of America. New York, New York: American Numismatic Society.

- Newman, Eric P.; Bressett, Kenneth E. (2009). The Fantastic 1804 Dollar (Tribute ed.). Racine, Wisconsin: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-2829-5.

- Nexsen, John A. (1891). "The 1804 Dollar". American Journal of Numismatics. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Numismatic Society. XXV.

- Nexsen, John A. (1905). "The 1804 Dollar". American Journal of Numismatics. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Numismatic Society. XXXIX.

- Numismatic News (June 28, 2012). "Cracking Down on Fakes". NumisMaster. Krause Publications. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- Rochette, Ed (May 25, 1997). "$1.8 Million Silver Dollar No 'Saigon Copy'". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. (subscription required)

- Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

- Ruddy, James F. (2005). Photograde: Official Photographic Grading Guide for United States Coins (19th ed.). Irvine, California: Bowers and Merena Galleries, Inc. ISBN 0-9742371-5-9.

- Treasury Department, Bureau of the Mint (1897). Laws of the United States Relating to the Coinage. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Trumble, Alfred, ed. (January 15, 1892). "That 1804 Dollar". The Art Collector. New York, New York. III (6).

- United States Congress (April 2, 1792). "Act of April 2, 1792" (PDF). United States Mint. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- United States Congress (February 9, 1793). "Act of February 9, 1793" (PDF). United States Mint. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- Yeoman, R.S. (2008). Kenneth Bressett (ed.). A Guide Book of United States Coins (62nd ed.). Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-2491-4.