1906 French Grand Prix

The 1906 Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France, commonly known as the 1906 French Grand Prix, was a motor race held on 26 and 27 June 1906, on closed public roads outside the city of Le Mans. The Grand Prix was organised by the Automobile Club de France (ACF) at the prompting of the French automobile industry as an alternative to the Gordon Bennett races, which limited each competing country's number of entries regardless of the size of its industry. France had the largest automobile industry in Europe at the time, and in an attempt to better reflect this the Grand Prix had no limit to the number of entries by any particular country. The ACF chose a 103.18-kilometre (64.11 mi) circuit, composed primarily of dust roads sealed with tar, which would be lapped six times on both days by each competitor, a combined race distance of 1,238.16 kilometres (769.36 mi). Lasting for more than 12 hours overall, the race was won by Ferenc Szisz driving for the Renault team. FIAT driver Felice Nazzaro finished second, and Albert Clément was third in a Clément-Bayard.

| 1906 French Grand Prix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

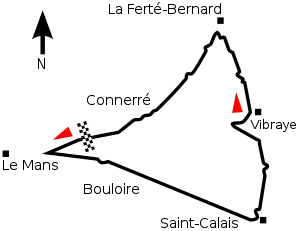

A roughly triangular track, with Le Mans at the western corner, La Ferté-Bernard at the north-east corner and Saint-Calais at the south-east corner. The track begins on the north-west side, and travels anti-clockwise.

| |||

| Race details | |||

| Date | 26 and 27 June 1906 | ||

| Official name | 9e Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France[note 1] | ||

| Location | Le Mans, France | ||

| Course | Public roads | ||

| Course length | 103.18 km (64.11 miles) | ||

| Distance | 12 laps, 1,238.16 km (769.36 miles) | ||

| Fastest lap | |||

| Driver |

| Brasier | |

| Time | 52:25.4 on lap 1 | ||

| Podium | |||

| First | Renault | ||

| Second | FIAT | ||

| Third | Clément-Bayard | ||

Paul Baras of Brasier set the fastest lap of the race on his first lap. He held on to the lead until the third lap, when Szisz took over first position, defending it to the finish. Hot conditions melted the road tar, which the cars kicked up into the faces of the drivers, blinding them and making the racing treacherous. Punctures were common; tyre manufacturer Michelin introduced a detachable rim with a tyre already affixed, which could be quickly swapped onto a car after a puncture, saving a significant amount of time over manually replacing the tyre. This helped Nazzaro pass Clément on the second day, as the FIAT—unlike the Clément-Bayard—made use of the rims.

Renault's victory contributed to an increase in sales for the French manufacturer in the years following the race. Despite being the second to carry the title, the race has become known as the first Grand Prix. The success of the 1906 French Grand Prix prompted the ACF to run the Grand Prix again the following year, and the German automobile industry to organise the Kaiserpreis, the forerunner to the German Grand Prix, in 1907.

Background

The first French Grand Prix originated from the Gordon Bennett races, established by American millionaire James Gordon Bennett, Jr. in 1900. Intended to encourage automobile industries through sport, by 1903 the Gordon Bennett races had become some of the most prestigious in Europe;[2] their formula of closed-road racing among similar cars replaced the previous model of unregulated vehicles racing between distant towns, over open roads. Entries into the Gordon Bennett races were by country, and the winning country earned the right to organise the next race.[3] Entries were limited to three per country, which meant that although the nascent motor industry in Europe was dominated by French manufacturers, they were denied the opportunity to fully demonstrate their superiority. Instead, the rule put them on a numerical level footing with countries such as Switzerland, with only one manufacturer, and allowed Mercedes, which had factories in Germany and Austria, to field six entries: three from each country.[4] The French governing body, the Automobile Club de France (ACF), held trials between its manufacturers before each race; in 1904 twenty-nine entries competed for the three positions on offer.[5]

When Léon Théry won the 1904 race for the French manufacturer Richard-Brasier, the French automobile industry proposed to the ACF that they modify the format of the 1905 Gordon Bennett race and run it simultaneously with an event which did not limit entries by nation.[2] The ACF accepted the proposal, but decided that instead of removing limits to entries by nation, the limits would remain but would be determined by the size of each country's industry. Under the ACF's proposal, France was allowed fifteen entries, Germany and Britain six, and the remaining countries—Italy, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria and the United States—three cars each.[6]

The French proposal was met with strong opposition from governing bodies representing the other Gordon Bennett nations, and at the instigation of Germany a meeting of the bodies was organised to settle the dispute. Although the delegates rejected the French model for the 1905 race, to avoid deadlock they agreed to use the new system of limits for the 1906 race. But when Théry and Richard-Brasier won again in 1905, and the responsibility for organising the 1906 race fell once more to the ACF, the French ended the Gordon Bennett races and organised their own event as a replacement, the Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France.[6]

Track

A combined offer from the city council of Le Mans and local hoteliers to contribute funding to the Grand Prix persuaded the ACF to hold the race on the outskirts of the city,[7] where the Automobile Club de la Sarthe devised a 103.18-kilometre (64.11 mi) circuit.[note 2][8][9] Running through farmlands and forests, the track, like most circuits of the time, formed a triangle. It started outside the village of Montfort, and headed south-west towards Le Mans. Competitors then took the Fourche hairpin, which turned sharply left and slowed the cars to around 50 kilometres per hour (31 mph), and then an essentially straight road through Bouloire south-east towards Saint-Calais. The town was bypassed with a temporary wooden plank road, as the track headed north on the next leg of the triangle. Another plank road through a forest to a minor road allowed the track to bypass most of the town of Vibraye, before it again headed north to the outskirts of La Ferté-Bernard. A series of left-hand turns took competitors back south-west towards Montfort on the last leg of the triangle, a straight broken by a more technical winding section, near the town of Connerré.[10][11] Competitors lapped the circuit twelve times over two days, six times on each day, a total distance of 1,238.16 kilometres (769.36 mi).[9]

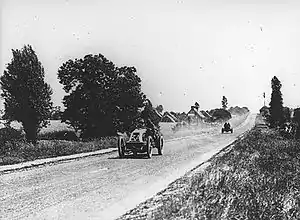

To address concerns about previous races, during which spectators crowding too close to the track had been killed or injured by cars, the ACF erected 65 kilometres (40 mi) of palisade fencing around the circuit, concentrated around towns and villages, and at the ends of lanes, footpaths and roads intersecting the track.[10] The planking used to avoid the towns of Saint-Calais and Vibraye was installed as an alternative to the system used in the Gordon Bennett races, where cars passing through towns would slow down to a set speed and were forbidden to overtake.[12] Several footbridges were erected over the track, and a 2,000-seat canopied grandstand was built at the start and finish line at Montfort. This faced the pit lane on the other side of the track, where the teams were based and could work on the cars. A tunnel under the track connected the grandstand and the pit lane.[11] The road surface was little more than compacted dust and sharp stones which could be easily kicked up by the cars, and to limit the resulting problem of impaired visibility and punctures the ACF sealed the entire length of the track with tar. More was added to the bends of the track after cars running on them during practice broke up the surface.[5][10]

Entries and cars

If we win the Grand Prix we shall let the whole world know that French motorcars are the best. If we lose it shall merely be by accident, and our rivals should then be grateful to us for having been sufficiently sportsmanlike to allow them an appeal against the bad reputation of their cars.

Le Petit Parisien, quoted in The Motor.[13]

Ten French manufacturers entered cars in the Grand Prix: Clément-Bayard, Hotchkiss, Gobron-Brillié, Darracq, Vulpes, Brasier (the successor to Richard-Brasier), Panhard, Grégoire, Lorraine-Dietrich and Renault. Two teams came from Italy (FIAT and Itala) and one (Mercedes) from Germany. With the exceptions of Gobron-Brillié and Vulpes, which each entered one car, and Grégoire, which entered two cars, each team entered three cars, to make a total field of thirty-four entries.[14] No British or American manufacturers entered the Grand Prix. The British were suspicious that the event was designed as propaganda for the French automobile industry; British magazine The Motor quoted French daily newspaper Le Petit Parisien as evidence of this supposed lack of sportsmanship.[13][15]

The ACF imposed a maximum weight limit—excluding tools, upholstery, wings, lights and light fittings—of 1,000 kilograms (2,205 lb), with an additional 7 kilograms (15 lb) allowed for a magneto or dynamo to be used for ignition.[16][17] Regulations limited fuel consumption to 30 litres per 100 kilometres (9.4 mpg‑imp; 7.8 mpg‑US).[16] Every team opted for a magneto system; all used a low-tension system except Clément-Bayard, Panhard, Hotchkiss, Gobron-Brillié, and Renault, which used high-tension.[13] Mercedes, Brasier, Clément-Bayard, FIAT and Gobron-Brillié used a chain drive system for transmission; the rest used drive shafts.[17] All entries were fitted with four-cylinder engines; engine displacement ranged from 7,433 cubic centimetres (454 cu in) for the Grégoire to 18,279 cubic centimetres (1,115 cu in) for the Panhard.[18] Exhaust pipes were directed upwards to limit the dust kicked up off the roads.[10] Teams were allowed to change drivers and equipment, but only at the end of the first day's running, not while the race was in progress.[19]

Michelin, Dunlop and Continental supplied tyres for the race.[20] In the Grand Prix's one major technical innovation, Michelin introduced the jante amovible: a detachable rim with a tyre already affixed, which could be quickly swapped onto the car in the event of a puncture. Unlike in the Gordon Bennett races, only the driver and his riding mechanic were allowed to work on the car during the race, hence carrying the detachable rims could save time and confer a large advantage. The conventional method of changing a tyre, which involved slicing off the old tyre with a knife, and forcing the new tyre onto the rim, generally took around fifteen minutes; replacing Michelin's rims took less than four.[21] The FIATs each used a full set, while the Renaults and two of the Clément-Bayards used them on the rear wheels of their cars.[14] As carrying each rim added 9 kilograms (20 lb) to the weight of the car over conventional wheels and tyres, some teams—such as Itala and Panhard—could not carry them without exceeding the weight limit.[5][14]

The Grand Prix name ("Great Prize") referred to the prize of 45,000 French francs to the race winner.[22] The franc was pegged to the gold at 0.290 grams per franc, which meant that the prize was worth 13 kg of gold.

Race

Roads around the track were closed to the public at 5 am on the morning of the race.[23] A draw took place among the thirteen teams to determine the starting order, and assign each team a number.[24] Each of a team's three entries was assigned a letter, one of "A", "B", or "C". Two lines of cars formed behind the start line at Montfort: cars marked "A" in one line and cars marked "B" in the other. Cars assigned the letter "C" were the last away; they formed a single line at the side of the track so that any cars which had completed their first circuit of the track would be able to pass. Cars were dispatched at 90-second intervals, beginning at 6 am.[note 3][23] Lorraine-Dietrich driver Fernand Gabriel (numbered "1A") was scheduled to be the first competitor to start, but he stalled on the line and could not restart his car before the FIAT of Vincenzo Lancia, who was next in line, drove away.[12] Renault's lead driver, the Hungarian Ferenc Szisz, started next, and behind him Victor Hémery of Darracq, Paul Baras of Brasier, Camille Jenatzy of Mercedes, Louis Rigolly of Gobron-Brillié and Alessandro Cagno of Itala. Philippe Tavenaux of Grégoire, scheduled next, was unable to start; the only other non-starter was the sole Vulpes of Marius Barriaux, which was withdrawn before the race when it was found to be over the weight limit. The last of the thirty-two starters—the Clément-Bayard of "de la Touloubre",[note 4] numbered "13C"—left the start line at 6:49:30 am.[18]

Itala driver Maurice Fabry started the fastest of the competitors; he covered the first kilometre in 43.4 seconds. Over the full distance of the lap Brasier's Baras was the quickest; his lap time of 52 minutes and 25.4 seconds (52:25.4) moved him up to third position on the road and into the lead overall.[5][25] A mechanical problem caused Gabriel to lose control of his car at Saint-Calais; he regained control in time to avoid a serious accident but was forced to retire.[26] Baras maintained his lead after the second lap, but fell back to second the next lap as Szisz took over the lead. As the day grew hotter the tar began to melt, which proved to be a greater problem than the dust; it was kicked up by the cars into the faces of the drivers and their mechanics, seeping past their goggles and inflaming their eyes.[5][25] The Renault driver, J. Edmond, was particularly affected: his broken goggles allowed more tar to seep past and rendered him nearly blind. His attempts to change the goggles at a pit stop were rejected by officials on the grounds that equipment could not be replaced mid-race. Nor could another driver be substituted; he continued for two more laps before retiring.[19]

FIAT driver Aldo Weilschott climbed from fourteenth on lap three to third on lap five, before his car rolled off the planks outside Vibraye.[27] Szisz maintained the lead he had gained on lap three to finish the first day just before noon in a time of 5 hours, 45 minutes and 30.4 seconds (5:45:30.4), 26 minutes ahead of Albert Clément of Clément-Bayard.[28] Despite a slow start, FIAT driver Felice Nazzaro moved up to third position, 15 minutes behind Clément. Seventeen cars completed the first day; Henri Rougier's Lorraine-Dietrich finished last with a time of 8:15:55.0, 2+1⁄2 hours behind Szisz.[27][28] All the cars that were competing the next day were moved into parc fermé, a floodlit area guarded overnight by members of the ACF, to prevent teams and drivers from working on them until the following morning.[27]

The time each car set on the first day determined the time they set off on the second day, hence Szisz's first-day time of 5 hours and 45 minutes meant he started at 5:45 am. Following the same principle, Clément began at 6:11 am and Nazzaro at 6:26 am. This method ensured that positions on the road directly reflected the race standings. A horse, which had been trained before the race to be accustomed to the loud noise of an engine starting, towed each competitor out of parc fermé to the start line.[29] As neither driver nor mechanic could work on their car until they had been given the signal to start the day's running, Szisz and Clément began by heading directly to the pit lane to change tyres and service their cars. Clément completed his stop more quickly than Szisz, and Nazzaro did not stop at all, and so Clément closed his time gap to Szisz and Nazzaro closed on Clément.[27] Jenatzy and Lancia, who were both experiencing eye problems from the first day, had intended to retire from the race and be relieved by their reserve drivers. As planned, "Burton" took over Jenatzy's car, but Lancia was forced to resume in his street clothes when his replacement driver could not be found when the car was due to start.[30]

Hotchkiss driver Elliott Shepard, who finished the first day in fourth, less than four minutes behind Nazzaro, spent half-an-hour working on his car at the start of the second day, fitting new tyres and changing liquids. On the eighth lap, he ran off the wooden planking at Saint-Calais but was able to resume; a wheel failure later in the lap caused him to run into a bank of earth and forced him to retire.[30][31] Panhard driver Georges Teste crashed early in the day and retired, as did Claude Richez of Renault; the sole Gobron-Brillié of Rigolly suffered radiator damage on lap seven and was forced out of the race.[32] After two laps' running on the second day, second-placed Clément had established a 23-minute lead over Nazzaro, but this was reduced to three minutes on the following lap. Despite Nazzaro passing Clément on lap ten, a refuelling stop for the FIAT soon after put Clément back in front. Nazzaro passed again, and led Clément into the last lap of the race by less than a minute.[32]

Szisz's Renault suffered a broken rear suspension on the tenth lap, but his lead was so great (more than 30 minutes) that he could afford to drive cautiously with the damage. He took the black flag of the winner at the finish line after a combined total from the two days of 12:12:07.0; he had also been quicker on the straight than any other driver, reaching a top speed of 154 kilometres per hour (96 mph).[5][33][34] He finished 32 minutes ahead of second-placed Nazzaro, who was in turn 3 minutes ahead of Clément. Jules Barillier's Brasier was fourth, ahead of Lancia and Panhard driver George Heath. Baras—whose first lap was the fastest of any car during the race—was seventh, ahead of Arthur Duray of Lorraine-Dietrich, "Pierry" of Brasier, and "Burton". The last finisher, the Mercedes driver "Mariaux", was eleventh, more than four hours behind Szisz. Rougier, who had set the fastest lap of the day with a time of 53:16.4, had retired on lap ten after a long series of punctures.[34] Of the other retirements, Hémery, René Hanriot (riding mechanic Jean Chassagne) and Louis Wagner of Darracq suffered engine problems; the radiators on the cars of Rigolly of Gobron-Brillié, Xavier Civelli de Bosch of Grégoire and Cagno of Itala failed; Pierre de Caters of Itala, Shepard and Hubert Le Blon of Hotchkiss, A. Villemain of Clément-Bayard and Vincenzo Florio of Mercedes withdrew after wheel failures; Gabriel of Lorraine-Dietrich, "de la Touloubre" of Clément-Bayard and Henri Tart of Panhard retired because of other mechanical problems; and Fabry of Itala, Weilschott of FIAT, Teste of Panhard, Richez of Renault and Jacques Salleron of Hotchkiss suffered crash damage. Edmond of Renault was the only competitor whose retirement was the result of driver injury.[34]

Post-race and legacy

The top three finishers were escorted to the grandstand to collect their trophies. In an interview after the race, Szisz reflected on the "anxiety" he had felt as he drove the final laps: "I feared something small which would take away victory at the moment when it had seemed to be won."[33] The prestige Renault gained from Szisz's victory led to an increase in sales for the company, from around 1,600 cars in 1906 to more than 3,000 a year later, and increasing to more than 4,600 in 1908.[35] But the race had not proven the superiority of the French motorcar; an Italian car had finished second and only seven of the twenty-three French cars that had started the race finished it.[34]

Reflections on the race by the organisers and the media generally concluded that the Grand Prix had been a poor replacement for the Gordon Bennett races. In part, this had been because the race was too long, and the system of starting the race—with each car leaving at 90-second intervals—had meant that there had been very little interaction between the competitors, simply cars driving their own races to time.[note 5][34][38] The ACF decided that too much pressure had been put on drivers and riding mechanics by forbidding others to work on the cars during the race.[39] It was also felt that the outcome of the race had been too dependent on the use of Michelin's detachable rims. Clément had driven the only Clément-Bayard to not have the rims, and it was thought that this contributed to Nazzaro passing him on the second day as he stopped to change tyres.[34][35] Despite this, the ACF decided to run the Grand Prix again the following year.[40] The publicity generated by the race prompted the German governing body to organise a similar event that favoured their own industry. The forerunner to the German Grand Prix, the Kaiserpreis (Kaiser's Prize) was raced in 1907.[40]

The conference held in 1904 to consider the French proposal for a change in formula to the Gordon Bennett races led to the formation of the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus (AIACR; the predecessor of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile), the body responsible for regulating international motorsport.[6][41] Although a smaller race held in 1901 had awarded the "Grand Prix de Pau", the 1906 race outside Le Mans was the first genuinely international race to carry the label "Grand Prix". Until the First World War it was the only annual race to be called a Grand Prix (often, the Grand Prix), and is commonly known as "the first Grand Prix".[5][16][41]

Classification

| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Laps | Time/Retired | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3A | Renault | 12 | 12:14:07.4 | |||

| 2 | 2B | FIAT | 12 | +32:19.4 | |||

| 3 | 13A | Clément-Bayard | 12 | +35:39.2 | |||

| 4 | 5B | Brasier | 12 | +1:38:53.0 | |||

| 5 | 2A | FIAT | 12 | +2:08:04.0 | |||

| 6 | 10A | Panhard | 12 | +2:33:38.4 | |||

| 7 | 5A | Brasier | 12 | +3:01:43.0 | |||

| 8 | 1C | Lorraine-Dietrich | 12 | +3:11:54.6 | |||

| 9 | 5C | Brasier | 12 | +4:01:00.6 | |||

| 10 | 6A | Mercedes | 12 | +4:04:35.8 | |||

| 11 | 6B | Mercedes | 12 | +4:34:44.4 | |||

| Ret | 1B | Lorraine-Dietrich | 10 | Punctures | |||

| Ret | 3C | Renault | 8 | Accident | |||

| Ret | 12C | Hotchkiss | 7 | Wheel | |||

| Ret | 4A | Darracq | 7 | Engine | |||

| Ret | 7A | Gobron-Brillié | 7 | Radiator | |||

| Ret | 10C | Panhard | 6 | Accident | |||

| Ret | 3B | Renault | 5 | Driver injury | |||

| Ret | 2C | FIAT | 5 | Accident | |||

| Ret | 6C | Mercedes | 5 | Wheels | |||

| Ret | 13B | Clément-Bayard | 4 | Wheels | |||

| Ret | 12A | Hotchkiss | 4 | Wheel | |||

| Ret | 10B | Panhard | 4 | Suspension | |||

| Ret | 13C | Clément-Bayard | 3 | Gearbox | |||

| Ret | 12B | Hotchkiss | 2 | Accident | |||

| Ret | 4B | Darracq | 2 | Engine | |||

| Ret | 8A | Itala | 2 | Radiator | |||

| Ret | 8C | Itala | 1 | Wheel | |||

| Ret | 1A | Lorraine-Dietrich | 0 | Radius rod | |||

| Ret | 8B | Itala | 0 | Accident | |||

| Ret | 9B | Grégoire | 0 | Radiator | |||

| Ret | 4C | Darracq | 0 | Engine | |||

| DNS | 9A | Grégoire | Non-starter | ||||

| DNS | 11A | Vulpes | Car overweight | ||||

Source:[34] | |||||||

See also

- Grand Prix motor racing

- 1908 New York to Paris Race

- 24 Hours of Le Mans, the world's oldest active endurance race, often called the "Grand Prix of Endurance and Efficiency".

Notes

- Beginning in the early 1920s, French media represented many races held in France before 1906—such as the Paris–Bordeaux–Paris race in 1895—as being Grands Prix de l'Automobile Club de France, despite their running pre-dating the formation of the Club. Hence, the 1906 race was said to have been the 9th edition of the Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France. The ACF itself adopted this reasoning in 1933, although some members of the Club dismissed it, "concerned the name of the Club was lent to the fiction simply out of a childish desire to establish their Grand Prix as the oldest race in the world."[1]

- The circuit was officially called the "Circuit de la Sarthe", but its only relation to the modern Circuit de la Sarthe is the club which designed it: the Automobile Club de la Sarthe, later the Automobile Club de l'Ouest.[5]

- Unlike the Gordon Bennett races, the Grand Prix did not require cars to be painted in the international racing colour of their manufacturer (for example, blue for France, red for Italy and white for Germany). Nevertheless, most cars continued to bear the colours.[23]

- Like other entrants "Pierry", "Burton" and "Mariaux", "de la Touloubre" is a pseudonym.

- By comparison, the 1905 Gordon Bennett race was only 548 kilometres (341 mi)—less than half the distance of the ACF's Grand Prix.[36] Cars in the 1905 race had set off at five-minute intervals, however, much longer than the 90-second intervals used in 1906.[37]

References

Citations

- Hodges (1967), pp. 2–3.

- Hodges (1967), p. 1

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 19

- Hilton (2005), p. 15

- Leif Snellman (27 May 2002). "The first Grand Prix". 8W. FORIX. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Hodges (1967), p. 2

- Rendall (1993), pp. 46–47.

- Clausager (1982), p. 11.

- Hodges (1967), p. 221.

- Hilton (2005), p. 16

- Hodges (1967), p. 222

- Pomeroy (1949), p. 21.

- Hodges (1967), p. 13

- Hodges (1967), p. 14

- Hilton (2005), pp. 15–16.

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 25.

- Pomeroy (1949), p. 20.

- Hodges (1967), pp. 13–14

- Hilton (2005), p. 22

- Hilton (2005), p. 17.

- Rendall (1991), p. 58.

- Grand Prix century – The Telegraph, 10 June 2006

- Hodges (1967), p. 15

- "Une Grand Épreuve Sportive: Le Grand Prix de l'ACF", La Presse (in French), Paris, vol. 73, no. 5138, p. 1, 26 June 1906

- Hodges (1967), p. 16.

- Hilton (2005), pp. 21–22.

- Hodges (1967), p. 17.

- Hilton (2005), p. 23

- Hilton (2005), p. 24

- Hilton (2005), p. 25

- Hodges (1967), p. 18

- Hodges (1967), pp. 18–19

- Hilton (2005), p. 26

- Hodges (1967), p. 19

- Rendall (1993), p. 49

- Cimarosti (1986), p. 24

- Rendall (1993), p. 41

- Hilton (2005), pp. 26–27.

- Rendall (1993), pp. 48–49.

- Pomeroy (1949), p. 22

- Hodges et al. (1981), p. 10

Sources

- Cimarosti, Adriano (1990) [1986], The Complete History of Grand Prix Motor Racing, David Bateman trans., New York: Crescent Books, ISBN 978-0-517-69709-2.

- Clausager, Anders D. (1982), Le Mans, London: A. Barker, ISBN 978-0-213-16846-9.

- Hilton, Christopher (2005), Grand Prix Century: The First 100 Years of the World's Most Glamorous and Dangerous Sport, Somerset: Haynes Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84425-120-9.

- Hodges, David (1967), The French Grand Prix: 1906–1966, London: Temple Press Books.

- Hodges, David; Nye, Doug; Roebuck, Nigel (1981), Grand Prix, London: Joseph, ISBN 978-0-7181-2024-5.

- Pomeroy, Laurence (1949), The grand prix car, 1906–1939, London: Motor Racing Publications.

- Rendall, Ivan (1991), The Power and the Glory: A Century of Motor Racing, London: BBC Books, ISBN 978-0-563-36093-3.

- Rendall, Ivan (1993), The Chequered Flag: 100 Years of Motor Racing, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-83220-1.