1991 Bangladesh cyclone

The 1991 Bangladesh cyclone was among the deadliest tropical cyclones on record.[1] Forming out of a large area of convection over the Bay of Bengal on April 24, the tropical cyclone initially developed gradually while meandering over the southern Bay of Bengal. On April 28, the storm began to accelerate northeastwards under the influence of the southwesterlies, and rapidly intensified to super cyclonic storm strength near the coast of Bangladesh on April 29. After making landfall in the Chittagong district of southeastern Bangladesh with winds of around 250 km/h (155 mph), the cyclone rapidly weakened as it moved through northeastern India, degenerating into a remnant low over the Yunnan province in western China.

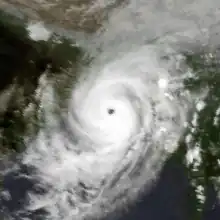

The cyclone near peak intensity approaching Bangladesh on April 29 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | April 24, 1991 |

| Dissipated | April 30, 1991 |

| Super cyclonic storm | |

| 3-minute sustained (IMD) | |

| Highest winds | 235 km/h (145 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 920 hPa (mbar); 27.17 inHg |

| Category 5-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 260 km/h (160 mph) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 138,866 (Fourth-deadliest tropical cyclone on record) |

| Damage | $1.7 billion |

| Areas affected | Bangladesh, Northeastern India, Myanmar, Yunnan |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1991 North Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

One of the most powerful tropical cyclones ever recorded in the basin, the tropical cyclone caused a 6.1 m (20 ft) storm surge, which inundated the coastline, causing at least 138,866 deaths and about US$1.7 billion (1991 USD) in damage. As a result of the catastrophic damage, the United States and other countries carried out Operation Sea Angel, one of the largest military relief efforts ever carried out.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On April 22, 1991, a circulation formed in the southern Bay of Bengal from a persistent area of convection, or thunderstorms, near the equator in the eastern Indian Ocean. Within two days, the cloud mass encompassed most of the Bay of Bengal, focused on an area west of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[2][3] On April 24, the India Meteorological Department (IMD)[nb 1] designated the system as a depression, and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)[nb 2] labeled the system as Tropical Cyclone 02B. Ships in the region reported winds of around 55 km/h (35 mph) around this time.[6]

From its genesis, the storm moved northwestward, and early forecasts from the JTWC anticipated that trajectory would continue toward Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India, due to a westward-moving ridge over India. The cyclone gradually strengthened, amplified by a wind surge from the south. The IMD upgraded the depression to a cyclonic storm on April 25, and to a severe cyclonic storm on the following day. By April 26, wind shear had decreased to near zero as an anticyclone developed aloft the hurricane. Around this time, the cyclone rounded the western periphery of a large subtropical ridge over Thailand, and the storm turned northward between the ridge to the northeast and northwest. The IMD upgraded the system to a very severe cyclonic storm on April 27, estimating winds of 142 km/h (89 mph). By this time, the JTWC anticipated a future track toward the Ganges Delta region of eastern India and Bangladesh.[6][2]

On April 28, the flow of the southwesterlies caused the cyclone to accelerate to the north-northeast. This flow also amplified the storm's outflow, and the cyclone intensified further. By 12:00 UTC on April 28, or about 31 hours before landfall, the JTWC was correctly forecasting a landfall in southeastern Bangladesh.[2] Early on April 29, the IMD upgraded the system to a super cyclonic storm – the highest category – and estimated peak winds of 235 km/h (145 mph). The JTWC estimated peak winds of 260 km/h (160 mph), the equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale or a super typhoon. The IMD also estimated a minimum barometric pressure of 918 hPa (27.11 inHg), while the JTWC estimated a minimum pressure of 898 hPa (26.52 inHg). The cyclone's high winds and low pressure, a rarity for the Bay of Bengal, ranked it among the most intense cyclones in the basin. At 19:00 UTC on April 29, the cyclone made landfall about 55 km (35 mi) south of Chittagong in southeastern Bangladesh while slightly below its peak strength. Moving through the mountainous terrain of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the cyclone quickly weakened and crossed into northeast India, where it degenerated into a remnant low-pressure area.[7][6][2]

Background and preparations

Until 2004, tropical cyclones were not named in the north Indian Ocean.[8] Through its role as Regional Specialized Meteorological Center, the IMD issued warnings on the storm, designating it Super Cyclonic Storm BoB 1. The agency tracked the storm using satellite imagery, radar, and other meteorological stations.[4][7] The JTWC, providing warnings and support to American military interests, designated the storm as Tropical Cyclone 02B, and also referred to it as a "super cyclone".[2] Although the cyclone was officially unnamed, documents from the United States Agency for International Development and the United States Army referred to the storm as Cyclone Marian.[9][10] Time magazine referred to the storm as Cyclone Gorky.[11]

The Bay of Bengal is prone to large storm surges, which is the rise in sea water accompanying a cyclone landfall. The low-lying coast of Bangladesh along the Bay of Bengal is heavily populated,[2] with at least 120 million people.[12] In 1970, a cyclone struck Bangladesh and killed at least 300,000 people.[2]

Before the cyclone moved ashore, an estimated 2–3 million people evacuated the Bangladeshi coast. In a survey by the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the main reason more people did not evacuate was underestimating the severity of the cyclone. The JTWC maintained contact with the American embassy in Bangladesh's capital Dhaka, assuring that it would not have to be evacuated due to a projected track farther southeast.[2]

Impact

The cyclone made landfall in southeastern Bangladesh around the time of high tide,[6] which was already 5.5 m (18 ft) above normal; in addition, the cyclone produced a 6.1 m (20 ft) storm surge that inundated the coastline. The storm also brought winds of around 240 km/h (150 mph).[2] Winds exceeding 220 km/h (135 mph) lashed a populated region of the coast for about 12 hours, as well as 12 offshore islands.[6]

An estimated 138,000 people were killed by the cyclone.[2] More than 20,000 people died on Kutubdia Upazila, an island offshore Chittagong where 80–90% of homes were destroyed, and all livestock were killed. Some smaller offshore islands lost their entire populations.[9] There were around 25,000 dead in Chittagong, 40,000 dead in Banshkali. About 13.4 million people were affected.[9] Around 1 million homes were destroyed, leaving 10 million people homeless.[2] The storm surge caused whole villages to be swept away.

The storm caused an estimated $1.5 billion (1991 US dollars) in damage.[13] The high velocity wind and the storm surge devastated the coastline. Although a concrete levee was in place near the mouth of the Karnaphuli River in Patenga, it was washed away by the storm surge. A large number of boats and smaller ships ran aground. The Bangladesh Navy and Bangladesh Air Force, both of which had bases in Chittagong, were also heavily hit. The Isha Khan Naval Base at Patenga was flooded, with heavy damages to the ships.[14] Most of the fighter planes belonging to the air force were damaged. The extensive damage caused the price of building materials to greatly increase. For an additional three to four weeks after the storm had dissipated, mass land erosion resulted in more and more farmers losing their land, and therefore, the number of unemployed rose.[15] In several areas up to 90 percent of crops had been washed away. The shrimp farms and salt industry were left devastated.

Elsewhere

The JTWC tracked the cyclone as moving northeastward from Bangladesh into northern Myanmar, dissipating in western China over Yunnan province.[3] In Northeast India, continuous rainfall and gusty winds affected Tripura and Mizoram states, causing "some loss of life" according to the IMD. Many houses in the two states were destroyed, and telecommunications were disrupted.[6]

Aftermath

In the days after the storm, homeless Bangladeshis overcrowded shelters, and many storm victims were unable to find shelter.

On the island of Sonodia its inhabitants were suffering from diarrhea from drinking contaminated water, respiratory and urinary infections, scabies and various injuries with only rice for food. Out of the ten wells on the island only 5 were functional of which only one providing pure water with the rest contaminated by sea water.

As a result of the 1991 cyclone, Bangladesh improved its warning and shelter systems.[16] Also, the government implemented a reforestation program to mitigate future flooding issues.[17]

A survey concluded that the cyclone mostly killed children of under 10 years of age and women above 40 years.[18]

Operation Sea Angel

The United States amphibious task-force, consisting of 15 ships and 2,500 men, returning to the US after the Gulf War was diverted to the Bay of Bengal to provide relief to an estimated 1.7 million survivors. This was part of Operation Sea Angel, one of the largest military disaster relief efforts ever carried out, with the United Kingdom, China, India, Pakistan and Japan also participating.[19]

Operation Sea Angel began on May 10, 1991, when President Bush directed the US military to provide humanitarian assistance.[20] A Contingency Joint Task Force under the command of Lieutenant General Henry C. Stackpole, consisting of over 400 Marines and 3,000 sailors, was subsequently sent to Bangladesh to provide food, water, and medical care to nearly two million people.[12] The efforts of U.S. troops, which included 3,300 tons of supplies, are credited with having saved as many as 200,000 lives.[21] The relief was delivered to the hard-hit coastal areas and low-lying islands in the Bay of Bengal by helicopter, boat and amphibious craft.

The US military also provided medical and engineering teams to work with their Bangladeshi counterparts[9] and international relief organisation to treat survivors and contain an outbreak of diarrhea, caused by contaminated drinking water. Water purification plants were built and prevalence of diarrhea amongst the population was reduced to lower than pre-cyclone levels.[22]

After the departure of the task force, 500 military personnel, two C-130 cargo planes, five Blackhawk helicopters and four small landing craft from the task force remained to help finish off relief operations in outlying districts and rebuild warehouses. The amphibious landing ship USS St. Louis (LKA-116) delivered large quantities of intravenous solution from Japan to aid in the treatment of cyclone survivors.[23][24]

See also

- 1970 Bhola cyclone – The deadliest tropical cyclone recorded worldwide

- 1988 Bangladesh cyclone – Another powerful cyclone that followed a similar path

- 1994 Bangladesh cyclone – Another powerful cyclone that followed a similar path

- Cyclone Amphan – Took a similar path and had a similar intensity

- Cyclone Sidr

- Cyclone Nargis

- Cyclone Mora

- List of Bangladesh tropical cyclones

- List of disasters in Bangladesh by death toll

Notes

- The India Meteorological Department became the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the northern Indian Ocean in 1988.[4]

- The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the northern Indian Ocean and other regions.[5]

References

- Unattributed (2008). "The Worst Natural Disasters by Death Toll" (PDF). NOAA Backgrounder. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy, United States Airforce. 1992. p. 155. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- "Tropical Cyclone 02B Best Track". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy, United States Airforce. December 1, 2002. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- Cyclone Warning Services in India (Report). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2011). "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". United States Navy, United States Airforce. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- Bangladesh Cyclone, April 24–30 1991 (PDF) (Report on Cyclonic Disturbances (Depressions and Tropical Cyclones) over North Indian Ocean in 1991). India Meteorological Department. January 1992. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 22, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- "IMD Best track data 1982-2022" (xls). India Meteorological Department. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- "Report on Cyclonic Disturbances Over North Indian Ocean During 2009" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 4, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- The Bangladesh Cyclone of 1991 (PDF) (Report). United States Agency for International Development. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Paul A. McCarthy (1994). Operational Sea Angel: A Case Study (PDF) (Report). RAND Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2012.

- Simon Robinson (November 19, 2007). "How Bangladesh Survived a Cyclone". Time. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- McCarthy, Paul A. (1994). Operation Sea Angel: A Case Study (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2012.

- "Weather Events: Significant Severe Cyclones Striking Bangladesh". www.islandnet.com. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- M.Z. Hossain; M.T. Islam; T. Sakai; M. Ishida (April 2008). "Impact of Tropical Cyclones on Rural Infrastructures in Bangladesh". Agricultural Engineering International: The CIGR Ejournal. X.

- "Bangladesh Survivors Desperate for Aid". NPR: Morning Edition. May 3, 1991.

- "Bangladesh cyclone of 1991 - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Bangladesh cyclone of 1991 | tropical cyclone". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- Bern, C.; Sniezek, J.; Mathbor, G. M.; Siddiqi, M. S.; Ronsmans, C.; Chowdhury, A. M.; Choudhury, A. E.; Islam, K.; Bennish, M.; Noji, E. (1993). "Risk factors for mortality in the Bangladesh cyclone of 1991". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 71 (1): 73–78. PMC 2393441. PMID 8440041.

- Pike, John. "Operation Sea Angel / Productive Effort". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- Berke, Richard L. (May 12, 1991). "U.S. Sends Troops to Aid Bangladesh in Cyclone Relief". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- "U.S. Forces Heading Home After Cyclone Mission". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. May 29, 1991. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- "1991 Cyclone relief" (PDF). US Navy. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 6, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- "Bangladesh Air Force in Disaster Management Activities". www.baf.mil.bd. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- "Armies help govts worldwide to tackle terror, disasters". The News International. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

External links

- Data on Bangladesh disasters from NIRAPAD disaster response organisation.

- Indian Cyclone Fact Sheet

- Bern C, Sniezek J, Mathbor GM, et al. (1993). "Risk factors for mortality in the Bangladesh cyclone of 1991". Bull. World Health Organ. 71 (1): 73–8. PMC 2393441. PMID 8440041.

- JTWC report