History of the British 1st Division during the World Wars

The 1st Division was an infantry division of the British Army that was formed and disestablished numerous times between 1809 and the present. It was raised by Lieutenant-General Arthur Wellesley for service in the Peninsular War (part of the Coalition Wars of the Napoleonic Wars). It was disestablished in 1814 but re-formed the following year for service in the War of the Seventh Coalition and fought at the Battle of Waterloo. It remained active in France until 1818, when it was disbanded. It was subsequently raised for service in the Crimean War, the Anglo-Zulu War, and the Second Boer War. In 1902, it was re-raised in the UK. This latter event saw the division raised as a permanent formation, rather than being formed on an ad hoc basis for any particular crisis.

| |

|---|---|

Divisional insignia during the Second World War. | |

| Active | 1809 – present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Anniversaries | Peninsular Day[1] |

| Engagements | |

| Website | Official website |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |

|

In 1914, the First World War broke out and the division fought on the Western Front throughout the entire period. In 1919, it was used to form the Western Division as part of the British Army of the Rhine occupation force in Germany. The 1st Division was reformed a few months later in the UK. In the inter-war period, it dispatched troops to take part in the Irish War of Independence, to take part in the Occupation of Constantinople, to oversee the 1935 Saar status referendum, and for service during the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. In the Second World War, the division fought in the Battle of France, was evacuated at Dunkirk in 1940 and fought in the Tunisian and Italian campaigns. It ended the war in the Middle East.

During the Cold War, it was garrisoned in various locations across Africa and the Middle East before it returned to the UK. It was then disbanded and reformed in Germany, where it became the 1st Armoured Division in the 1970s. It latter fought in the Gulf War, served in Bosnia, took part in the Iraq War, and in 2014 was renamed the 1st (United Kingdom) Division.

Background

The 1st Division was formed on 18 June 1809, by Lieutenant-General Arthur Wellesley, commander of British forces in Spain and Portugal, for service during the Peninsular War.[2][3] After the conclusion of the War of the Sixth Coalition, it was broken-up only to be reformed the following year when the War of the Seventh Coalition began. The division subsequently fought at the battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo.[2][4][5] With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the division became part of the Army of Occupation based in France where it remained until December 1818, when it was disbanded upon the British withdrawal.[6][7]

Over the course of the 19th century, the division was raised on three more occasions for service in the Crimean War, the Anglo-Zulu War, and the Second Boer War.[2] In response to the lessons learnt following the latter, reforms were initiated throughout the British military. This included the founding of a permanent 1st Division in 1902, rather than one having to be formed on an ad hoc basis for a particular crisis or war.[8] The Haldane Reforms of 1907 saw additional changes. The division became part of Aldershot Command and had artillery, signals, and Royal Engineers permanently attached. It was also increased from two to three brigades to comprise the 1st Brigade based at Aldershot, the 2nd Brigade at Blackdown, and the 3rd Brigade at Bordon.[9][10] It subsequently took part in the Army Manoeuvres of 1912 and 1913.[11]

First World War

The division was a permanently established Regular Army division that was amongst the first to be sent to France at the outbreak of the First World War. It served on the Western Front for the duration of the war. On 31 October 1914 divisional commander General Samuel Lomax was seriously wounded by a shell and died on 10 April 1915, never having recovered from his wounds.[12] The division's insignia was the signal flag for the 'Number 1'. During the war, the division fought in the Battle of Mons, First Battle of the Marne, First Battle of the Aisne, First Battle of Ypres, Battle of Aubers Ridge, Battle of Loos, Battle of the Somme, Battle of Pozières, Third Battle of Ypres, Battle of Épehy. The division suffered 16,000 men killed in action.[13]

Interwar period

With the Armistice of 11 November 1918 ending the First World War, the Allied Powers agreed to occupy the Rhineland as a way to guarantee future reparation payments. On 18 November, after a six-day grace period during which only German forces were allowed to move, the 1st Division started towards Germany, crossed the frontier on 16 December, and reached the Bonn area on 24 December.[14][15] In January 1919, the occupation force became the British Army of the Rhine and demobilisation of veterans began. Starting at a rate of 1,200 men per day, this increased to 2,400 by the end of the month with drafts of teenagers replacing them.[16] In March, the division was redesignated as the Western Division and ceased to exist.[17]

The 1st Division reformed at Aldershot on 4 June 1919, and became the only UK-based formation maintained in a state of readiness that could be deployed in an emergency.[18][19] It dispatched troops to reinforce the British Army in Ireland during the Irish War of Independence and later to assist in the occupation of Constantinople.[20] Annual training also resumed and 1924 marked the first large scale exercise conducted since the Army Manoeuvres of 1913. During the 1924 exercise, held between August and September, the division undertook brigade training around Aldershot before conducting division-level training in the New Forest.[19][21] On 10 June 1925, George V reviewed the formation.[22] At La Groise, France, on 16 April 1927, Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch unveiled a memorial dedicated to the division's fallen. The site was chosen to commemorate actions fought by the division in August 1914 and November 1918.[13]

In December 1934, divisional engineers and signal personnel went to the Territory of the Saar Basin. They assisted international supervisors who oversaw the 1935 Saar status referendum.[20][23] In July 1935, the division was again observed by the king when they took part in a military review.[24] The following year, in September, it deployed to Mandatory Palestine to bolster the British presence during the opening stages of the Arab Revolt. The 1st and the 3rd Brigades moved to Jerusalem, while the 2nd Brigade went to Sarafand al-Amar to guard the southern coast. In December, with the exception of the 2nd Brigade, all returned to the UK.[20][25] The 2nd Brigade left Palestine in late 1937 and returned to the division by December.[26]

During the course of 1937, the division was mechanised and reorganised in line with new thinking. This saw each brigade decreased from four to three battalions, anti-tank companies added, and saw the arrival of Universal Carriers and more transport to make the infantry more mobile.[27] In September, army manoeuvres were conducted in East Anglia to test the changes. The 1st Division played the role of insurgents who had seized London (portrayed by Norwich) who were then attacked by pro-government forces who were portrayed by the 2nd Division.[28]

On 14 February 1938, Major-General Harold Alexander took command of the division and would lead them into the opening stages of the Second World War.[29][30] The second half of the 1930s saw tensions increased between Germany and the UK and its allies. War had been avoided in 1938 via the Munich Agreement, but relations between both parties soon rapidly deteriorated. In March 1939, Germany occupied the remnants of Czechoslovak breaching the agreement reached at Munich.[31] In May, Alexander joined high ranking British officers who were dispatched to France to undertake staff talks with their French counterparts. This was followed by a tour of the Maginot Line. The division itself continued training through the year, with the final excerise occurring between 28 and 30 August.[32] By the outbreak of the war, now known as the 1st Infantry Division, the division consisted of the 1st Infantry Brigade (Guards) as well as the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Brigades.[29][lower-alpha 1]

Second World War

Battle of France

The UK declared war on Germany, on 3 September 1939, following their invasion of Poland. The 1st Infantry Division landed in France on 20 September 1939 and arrived on the Franco–Belgian border on 3 October. Along with the three other divisions of the BEF, it was based east of Lille.[29][35] During the rest of the year and into 1940, training took place as well as the construction of field fortifications. David Fraser, a historian and former British general, wrote that the regular formations of the BEF were well-trained in small arms, but lacked tactical skill. Though mobile, the formations lacked specialist weapons, ammunition, spare parts, and communication equipment because of the budget cuts of the inter-war period.[36]

On 10 May 1940, Germany invaded Belgium. In response, the Anglo–French armies moved into Belgium in accordance with the Allied Dyle Plan. The division reached the River Dyle without difficulties. Although tactical success was achieved in its first action on 15 May, strategic developments forced the BEF to withdraw the next day towards the Escaut.[37][38] The 3rd Infantry Brigade provided a rearguard and was attacked on 18 May, was almost cut off but was able to extradite itself with the support of the divisional artillery. A few days later, the division fought back an assault on their position at the Escaut. The British official campaign history alleged that the Germans preceded their attack with troops dressed as civilians or British officers. On 23 May, a further withdrawal took place as the division moved back to defend the western bank of the Lys.[39] Three days later, with the majority of the BEF now bound within a closing perimeter on the French coast and lacking the ability to hold the position, the decision was made to evacuate from Dunkirk, the only remaining port in British hands.[40] By the end of the month, three of the division's battalions were dispatched to reinforce the 5th Infantry Division while the main body of the 1st Infantry Division withdrew into the newly established Dunkirk perimeter. The divisional engineers constructed a makeshift pier from lorries at Bray-Dunes, which became vital once small ships arrived to help with the evacuation. Meanwhile, the division's infantry (alongside the 46th Infantry Division) defended the Canal de Bergues between Bergues and Hoymille. On 31 May/1 June, they were heavily attacked; some positions were retained while others were breached and the troops forced back to the Canal des Chats. During this fighting, Captain Marcus Ervine-Andrews earned the Victoria Cross.[41] By the end of the next day, the division had been evacuated back to the UK.[29] The 1st Battalion, King's Shropshire Light Infantry, provided the division's rearguard and left via the Dunkirk mole on the ferry St Helier, alongside the final remnants of the BEF that had made it to Dunkirk, just prior to midnight. Left within the heavily damaged town, was upwards of 30,000 French soldiers who covered the final stage of British withdrawal.[42]

Home defence

Once back in the UK, the division moved to Lincolnshire to defend the coast, and to partially replace the 2nd Armoured Division that was relocated and the 66th Infantry Division that had been broken-up.[43][44] It remained through 1941, during which time it moved further inland to act as a reserve as the Lincolnshire County Division took over coastal defence. From its return from France, the division was seen as one of the better equipped and trained formations based in the UK, and was held in a reserve role to be rushed to southern England in the event of a German invasion.[45][46] During this period, the Guards Brigade was replaced by the 38th (Irish) Infantry Brigade.[29]

In 1942, the division moved to East Anglia and in June reorganised as a mixed division.[29] This concept called for an infantry division to have one infantry brigade removed and for it to be replaced by a brigade of tanks. To this point in the war, British tank brigades–containing infantry tanks–were independent formations allocated to higher commands and assigned to subordinate formations as needed. This move, to incorporate them into divisions, was described by Lieutenant-General Giffard Le Quesne Martel, commander of the Royal Armoured Corps, as "the absorption of the armoured forces into the rest of the army".[47][lower-alpha 2] In June, the 34th Tank Brigade joined the division and the Irish brigade left in early July to bring the division into conformation with the new organisation.[29] Despite battle drill existing for infantry-tank co-operation, training between the infantry and the tank brigade did not start until August.[50] The following month, the 34th were replaced by the 25th Tank Brigade.[29] The mixed concept was found not to be successful as it left the division with too few infantry.[47] This resulted in a revision to an infantry division organisation in November, when the 25th Tank Brigade departed and were replaced by the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards).[29] In 1943, the division joined the forming First Army and departed the UK on 28 February bound for North Africa.[29]

Tunisian campaign

The division arrived in North Africa on 9 March 1943 and moved to the Medjez-Bou Arada area of Tunisia. It joined the ongoing Tunisian campaign, by conducting patrols over the following weeks.[29][51] On 4 April, it was temporarily redesignated as the 1st British Infantry Division, to avoid confusion with the US 1st Infantry Division that was also active in the campaign.[52] Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen von Arnim, commander of the Axis Panzer Army Africa, was aware that Allied forces were intending to launch a major offensive. To attempt to cause delays, he approved for the Division Hermann Göring and the 334th Infantry Division to attack, supported by the 10th Panzer Division and Tiger I tanks. On 21 April, six German battalions attacked the British 1st and the 4th Divisions near Medjez el Bab. The 3rd Brigade, holding a ridgeline nicknamed 'Banana Ridge', bore the brunt of the attack in the division's sector. While the German assault caused a potentially dangerous situation to arise for artillery that had been moved forward in preparation for the Allied offensive, it was repulsed with just 106 casualties among the 1st Division. Thirty-three German tanks and 450 prisoners were claimed. The next morning, Operation Vulcan began, which was intended to be the final Allied effort in the Tunisian campaign and to capture Tunis.[53][54]

Two days later, the 1st Division began their part of the operation. Backed by massed artillery and 45 tanks of the 142nd Regiment Royal Armoured Corps, the 2nd Brigade assaulted a ridge between Grich el Oued and Gueriat el Atach. Initial success was thwarted by the inability to dig in and construct defensive fighting positions and a swift German counterattack. Back and forth fighting continued throughout the day, resulting in the ridge remaining in German hands. The 2nd Brigade suffered over 500 casualties and 29 of the supporting tanks were rendered disabled or destroyed. Notably, Lieutenant Willward Alexander Sandys-Clarke was posthumously awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions during this fighting. The next day, 24 April, the 3rd Brigade launched a new attack and seized the ridge. They were then subjected to German bombardments and suffered over 300 casualties.[55][56] On 27 April, the division's next major attack started when the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards) attacked Djebel bou Aoukaz, another defended ridge. The initial attack was almost successful, but ultimately failed. A renewed effort the following day seized the ridge, but it was lost following a German counterattack by elements of the 10th Panzer Division. With the overall Allied advance having slowed, Operation Vulcan came to end 25 miles (40 km) short of Tunis. However, the division continued back and forth fighting until the ridge was eventually secured on 5 May. The fighting resulted in over 300 casualties in one battalion, and two more Victoria Crosses being earned by members of the division.[57][58] The capture of Djebel bou Aoukaz secured the flank for the new offensive, which started on 6 May and used forces other than the 1st Division. Tunis was captured the following day, and Axis forces in North Africa capitulated on 12 May 1943.[59]

Pantelleria

Pantelleria, part of the Pelagie Islands, is located between Sicily and Tunisia. The Italians had fortified the island as a strategic counterweight to Malta. By 1943, it was garrisoned by 12,000 troops (five untried battalions supported by militia), contained radar sites that could track movement from North Africa towards Italy, and included an airbase with underground hangers. With Axis forces defeated in North Africa, the Allied powers set their sights on Sicily and made the decision to capture Pantelleria (Operation Corkscrew) as a prelude to the Allied invasion of Sicily. To avoid the need for a bloody assault, which would be conducted by the 1st Infantry Division, the island was subjected to a heavy aerial bombardment. From 18 May until 11 June, around 6,400 long tons (6,500 t) of bombs were dropped.[60][61] Unbeknown to the Italian garrison, the ships carrying the 1st Division arrived 8 miles (13 km) offshore on the morning of 11 June. Around the same time, the ranking members of the Italian garrison held a conference where they acknowledged their situation was untenable and made the decision to surrender. The latter coincided with the start of the division's landing operations. Under the cover of fighters, a final bombing raid, and naval gunfire, the 1st Division came ashore around noon and were greeted by white flags. The remaining Pelagie Islands were taken the next day, without incident. With the islands secured, the division was withdrawn back to North Africa on 14 June. Four days later, the first Allied aircraft started operating from the island and would go on to provide air cover during the assault on Sicily.[29][62] The capture of Pantelleria resulted in a German decision to send additional troops to Sardinia and Sicily. Allied deception, however, had convinced the Germans that it was just the first step in a series of attacks that would conclude with an invasion of Greece.[63]

Anzio landing

Back in North Africa, the division trained and guarded prisoners of war. This lasted until early December 1943, when it was transferred to Italy and concentrated near Cerignola in preparation to join the Eighth Army fighting on the east coast of the country.[29][64] In the preceding months, Allied forces had landed in southern Italy, accepted the surrender of Italy, and pushed German forces north to where they entrenched along the Winter Line barring the Allies from capturing Rome. From late September onwards, consideration for an amphibious landing behind the front line were made, but logistical and strategical constraints delayed such a venture from gaining traction until the end of the year. Anzio, south of Rome, was chosen as the landing site. The Fifth Army, fighting on the west coast of Italy, was assigned the dual task of advancing north through the Winter Line and conducting the landing. The division was allocated to the Fifth Army to take part in the operation. Accordingly, it moved to the Salerno-Naples area in early January and started specialized training on 14 January 1944. Between 17 and 19 January, Exercise Oboe was conducted in the Bay of Salerno. This was a full-scale rehearsal for the 2nd Infantry Brigade, which would land first, while elements from the rest of the division took part on a scaled down level. The day after the exercise ended, the division joined the US VI Corps that was to oversee the landing for Fifth Army.[65]

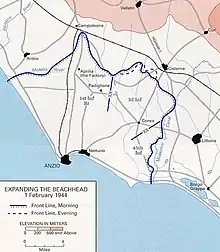

The initial assault was carried out by the 2nd Infantry Brigade (reinforced with tanks, reconnaissance troops, artillery, engineers, and additional infantry), while the rest of the division was held as a floating reserve to be committed as needed across the entire landing zone. Just after 02:00, on 22 January, the 2nd Brigade went ashore and advanced inland against little resistance. The rest of the division started to land a few hours later and were all ashore by the end of the next day although still in a reserve role. During the day, the first German counterattacks began when several infantry companies attacked the 2nd Brigade and were repulsed. On 24 January, the division was relieved of its reserve duties and its forward patrols reached Aprilia (nicknamed 'the factory' by the advancing troops) as well as positions along the Moletta River to secure the left flank of the landing zone. By this point, German troops from Germany, France, Yugoslavia, and elsewhere in Italy had started to redeploy to oppose the landing.[66][67][68]

Route 7, a highway and a vital supply line from central Italy to German forces based at the Winter Line, passes through Cisterna di Latina. The town was thus a target of the Allied landing. Carroceto and Aprilia were captured on 25 January, as the division worked to assist VI Corps achieve this goal. Over the course of the following days, patrols were conducted, minor tactical gains were made, and the division fended off several further German counterattacks that saw at least one British company overrun.[69][70][71] While the initial corps-wide attack had failed, a renewed effort began on 30 January after sufficient forces had landed and the corps had secured its logistical base. For the divisions part, it had to advance towards Albano Laziale and Genzano di Roma, with the aim to create conditions for the US 1st Armored Division to exploit potentially towards Rome. While the division reached Campoleone, it was unable to push beyond, and the US tanks failed to make their own impact due to mud and terrain limitations. The division regrouped to consolidate the ground captured, a salient 7,000 yards (6,400 m) deep.[72][73][74] By early February, the Germans had assembled a force that was almost on parity with the Allied forces in the bridgehead. On the division's front, between 3–4 February, German efforts concentrated on destroying the salient. Due to terrain, some the division's units were not able to set up mutually supporting positions and this was exploited by the German who infiltrated between them. While some of the initial German attacks were fought back, some British positions were overrun, or the troops forced to fall back. By the end of 4 February, the German assault had forced the division back to the positions held on 30 January and had inflicted 1,400 casualties.[75][76][77] Further German attacks steadily gained ground and by the end of 10 February, Aprilia and Carroceto had also been lost by the division.[78] It then moved into reserve. During this period, the divisional commander Major-General Ronald Penney was wounded necessitating several days away.[29][79][80]

Stalemate at Anzio

There was severe fighting throughout the next few weeks as the Germans launched several fierce counterattacks in an attempt to drive the Allied force back into the sea. Testimony to this was when, on 17 February, Penney was wounded by shellfire and command of the 1st Division was taken by Major General Gerald Templer of the recently arrived 56th (London) Infantry Division, from 18 to 22 February, when Penney resumed command.[81] Because of the fighting seen by the division throughout February and March, the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards) was withdrawn from the division, due to a lack of Guards replacements (even at this stage of the war the Guards were the only infantry regiments in the British Army to receive drafts of replacements from their own regiment), and replaced by the 18th Infantry Brigade from the 1st Armoured Division, which was in North Africa at the time.[82]

Operation Diadem was the final battle for Monte Cassino the plan was the U.S. II Corps on the left would attack up the coast along the line of Route 7 towards Rome. The French Expeditionary Corps (CEF) to their right would attack from the bridgehead across the Garigliano into the Aurunci Mountains. British XIII Corps in the centre right of the front would attack along the Liri valley whilst on the right 2nd Polish Corps would isolate the monastery and push round behind it into the Liri valley to link with XIII Corps. I Canadian Corps would be held in reserve ready to exploit the expected breakthrough. Once the German Tenth Army had been defeated, the U.S. VI Corps would break out of the Anzio beachhead to cut off the retreating Germans in the Alban Hills.[83]

As the Canadians and Polish launched their attack on 23 May, Major General Lucian Truscott, who had replaced Lucas as commander of U.S. VI Corps, launched a two pronged attack using five (three American and two British) of the seven divisions in the bridgehead at Anzio. The German 14th Army facing this thrust was without any armoured divisions because Kesselring had sent his armour south to help the German 10th Army in the Cassino action. The 18th Infantry Brigade, which was temporarily attached to the division from February to August, returned to command of the 1st Armoured Division and were replaced by the 66th Infantry Brigade became a part of the division for the rest of the war.[84]

In the fighting for the Anzio beachhead, 8,868 officers and men of the 1st Infantry Division were killed, wounded or missing in action.

Post war

After the war, the division only remained in Palestine for a short time. It was transferred to Egypt for a few months before going back to Palestine in April 1946. Two years later, as the British mandate over Palestine ended, the division returned to Egypt, also spending periods in Libya up until 1951. In October of that year, as British forces pulled out of Egypt outside of the Suez Canal Zone, the division garrisoned that small area. After British forces withdrew from Egypt, the division returned to the UK for a short while in 1955 and 1956.[85] It remained in the until 30 June 1960, when it was disbanded due to there being no need for an additional divisional headquarters in the UK. It was reformed the following day, when the 5th Division was renamed. The new division was based in Germany as part of the British Army of the Rhine.[86][87] During April 1978, a reorganised took place and the formation was renamed the 1st Armoured Division. Under this banner, in 1990–1991, it fought in the Gulf War.[88] When the Cold War ended, the British government restructured the army as part of Options for Change and this saw the division again disbanded on 31 December 1992. In 1993, the 4th Armoured Division, based in Germany, was renamed as the 1st (United Kingdom) Armoured Division.[89] During the 1990s, the division was deployed to Bosnia as part of peacekeeping efforts and in the 2000s fought in the Iraq War.[90] In 2014, the division was redesignated as the 1st (United Kingdom) Division in 2014.[91]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- 1st Infantry Division is the title used in the official publication for the British order of battle during the Second World War.[29] Other government publications as well as those made by the division itself, refer to the formation simply as the 1st Division.[33][34]

- Infantry tanks were initially designed to be heavily armoured and slow moving, so to provide intimate support to infantry.[48] Pre-war doctrine called for independent tank brigades, equipped with infantry tanks, to be attached to an infantry division as needed to assist in penetrating enemy defensive positions. Such penetrations would then be exploited by more mobile forces such as an armoured division.[49]

Citations

- 1 (UK) Division (6 July 2022). "1 (UK) Division". Twitter. Retrieved 6 July 2022., 1 (UK) Division (22 July 2021). "1 (UK) Division". Twitter. Retrieved 22 July 2021., 1 (UK) Division (10 September 2020). "1(UK) Division". Twitter. Retrieved 10 September 2020., and 1 (UK) Division (14 June 2019). "1 (UK) Division". Twitter. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "1st (UK) Division". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- Haythornthwaite 2016, The Divisional System.

- Oman 1930, pp. 496, 504–513, 561.

- Siborne 1900, pp. 186–190, 339–342, 521, 570.

- Ross-of-Bladensburg 1896, pp. 48–50.

- Veve 1992, p. 159.

- Satre 1976, p. 117, 121.

- "Hart's Annual Army List, 1909". National Library of Scotland. pp. 97–98.

- Dunlop 1938, pp. 245, 262.

- Whitmarsh 2007, pp. 337, 343.

- Davies and Maddocks 1995, p. 83

- "War Memorial To 1st Division". The Times. No. 44557. 16 April 1927. p. 9.

- Becke 1935, p. 39.

- Pawley 2007, p. 2–3.

- Pawley 2007, pp. 25, 29.

- Kennedy & Crabb 1977, p. 243.

- "War Office, Monthly Army List, December 1920". London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1920. p. 29.

- "Army Exercises". The Times. No. 43747. 3 September 1924. p. 7.

- Lord & Watson 2003, p. 24.

- "First Division On The March". The Times. No. 43443. 11 September 1923. p. 7. and "Army Training". The Times. No. 43644. 6 May 1924. p. 15.

- "The King's Review To-Day At Aldershot". The Times. No. 43984. 10 June 1925. p. 5.

- "Troops For Saar". The Times. No. 46936. 13 December 1934. p. 15.

- "The Aldershot Review". The Times. No. 47114. 12 July 1935. p. 9.

- "British Troops In Palestine". The Times. No. 47488. 24 September 1936. p. 12. and "The Army: Return of the 1st Division". The Times. No. 47562. 19 December 1936. p. 10.

- "British Troops in Palestine: Reliefs This Winter". The Times. No. 47765. 17 August 1937. p. 10., "War Office, Monthly Army List, November 1937". National Library of Scotland. p. 22. Retrieved 20 December 2022. and "War Office, Monthly Army List, December 1937". National Library of Scotland. p. 22. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- "Reorganizing the Infantry". The Times. No. 47562. 1 March 1937. p. 8.

- "The Army". The Times. No. 47768. 20 August 1937. p. 15. and ""Civil War" In England". The Times. No. 47785. 9 September 1937. p. 17.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 35–36.

- "No. 34487". The London Gazette. 25 February 1938. p. 1261.

- Bell 1997, pp. 3–4, 258–278, 281.

- "British Generals In France". The Times. No. 48300. 9 May 1939. p. 14. and "Militiamen For A.A. Defences". The Times. No. 48389. 21 August 1939. p. 17.

- 1st Division 1944, p. 9.

- "War Office, Monthly Army List, August 1939 Security Edition". National Library of Scotland. p. 42. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 15–17.

- Fraser 1999, pp. 28–29.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 23, 39, 46, 63, 67.

- Fraser 1999, pp. 30, 55–57.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 69, 100, 121, 193.

- Fraser 1999, pp. 67–69.

- Ellis 1954, pp. 193, 205, 232, 242–243.

- Thompson 2009, p. 269.

- Collier 1957, p. 219.

- Newbold 1988, p. 201.

- Newbold 1988, p. 262, 282–283, 367.

- Collier 1957, p. 229.

- Crow 1972, pp. 35–36.

- Crow 1972, p. 11.

- French 2001, pp. 37–41.

- Place 2000, p. 134.

- Blaxland 1977, pp. 227, 235.

- Playfair et al. 2004, p. 364.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 430, 434.

- Blaxland 1977, p. 236.

- Playfair et al. 2004, p. 437.

- Blaxland 1977, p. 242.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 438–439, 441, 449.

- Atkinson 2002, p. 498.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 441, 449, 452 457–458.

- Molony et al. 2004, p. 49.

- Garland & McGaw Smyth 1993, pp. 69–71, 572.

- Garland & McGaw Smyth 1993, pp. 71–73, 119.

- Garland & McGaw Smyth 1993, pp. 75, 203.

- 1st Division 1944, pp. 9–10.

- Joslen 2003, pp. 35–36; 1st Division 1944, pp. 10–17; Blumenson 1993, pp. 235–242; Molony et al. 2004, pp. 213–216, 594, 650.

- 1st Division 1944, pp. 12, 19–23, 26.

- Molony et al. 2004, pp. 651, 668–669.

- Blumenson 1993, p. 363.

- 1st Division 1944, pp. 25–31.

- Molony et al. 2004, pp. 675–677.

- Blumenson 1993, p. 387.

- 1st Division 1944, pp. 32–40.

- Molony et al. 2004, pp. 674–677.

- Blumenson 1993, pp. 389–390.

- 1st Division 1944, pp. 48–52.

- Molony et al. 2004, pp. 726, 727–729.

- Blumenson 1993, p. 392.

- 1st Division 1944, p. 53.

- Molony et al. 2004, p. 746.

- Blumenson 1993, pp. 421.

- Mead, p. 343

- Sheehan, p. 159

- Sheehan, p. 186

- "1st Infantry Division". Unit Histories. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Lord, Cliff; Watson, Graham (2004). The Royal Corps of Signals: Unit Histories of the Corps (1920–2001) and its antecedants. Helion and Co. p. 25. ISBN 978-1874622925.

- Lord & Watson 2003, p. 25; Smart 2005, Murray, General Sir Horatius (1903–1989), GCB, KBE, DSO.

- "Army Notes". Royal United Services Institution. 95:579 (579): 524. 1950. doi:10.1080/03071845009434082.

- Lord & Watson 2003, p. 25; Blume 2007, p. 7.

- Blume 2007, p. 7; Heyman 2007, p. 36.

- Tanner 2014, pp. 50–51.

- Kemp, Ian (2020). "The UK's Armoured Fist". EDR Magazine (European Defence Review). No. 52 July/August 2020: 30–40.

References

- 1st Division (1944). History of the First Division: Anzio Campaign, January–June 1944. Jerusalem, Palestine: "Ahva" Printing Press. OCLC 1281661223.

- Atkinson, Rick (2002). An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943. Vol. I. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-80506-288-5.

- Atkinson, Rick (2007). The Day of Battle. Vol. II. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-6289-2.

- Becke, Archibald Frank (1935). Order of Battle of Divisions Part 1: The Regular British Divisions. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 929528172.

- Bell, P. M. H. (1997) [1986]. The Origins of the Second World War in Europe (2nd ed.). London: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-582-30470-3.

- Bidwell, Shelford; Graham, Dominick (1986). Tug of War: The Battle for Italy 1943–1945. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-82323-8.

- Blaxland, Gregory (1977). The Plain Cook and the Great Showman: The First and Eighth Armies in North Africa. London: Kimber. OCLC 642072863.

- Blaxland, Gregory (1979). Alexander's Generals (The Italian Campaign 1944–1945). London: William Kimber. ISBN 978-0-7183-0386-0.

- Blume, Peter (2007). BAOR The Final Years: Vehicles of the British Army of the Rhine 1980 – 1994. Erlangen, Germany: Tankograd Publishing. OCLC 252418281.

- Blumenson, Martin (1993) [1969]. The Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino. United States Army in World War II. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History. OCLC 1023861933.

- Collier, Basil (1957). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Defence of the United Kingdom. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. London: HMSO. OCLC 375046.

- Crow, Duncan (1972). British and Commonwealth Armoured Formations (1919–46). AFV/Weapons series. Windsor: Profile Publications Limited. ISBN 978-0-853-83081-8.

- Dunlop, John K. (1938). The Development of the British Army 1899–1914. London: Methuen. OCLC 59826361.

- Ellis, Lionel F. (1954). Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 1087882503.

- Fraser, David (1999) [1983]. And We Shall Shock Them: The British Army in the Second World War. London: Cassell Military. ISBN 978-0-304-35233-3.

- French, David (2001) [2000]. Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War Against Germany 1919–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19924-630-4.

- Garland, Albert; McGaw Smyth, Howard (1993) [1965]. The Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Sicily and the Surrender of Italy. United States Army in World War II. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History. OCLC 894759669.

- Heyman, Charles (2007). The British Army Guide 2008–2009. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-783-40811-5.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2016). Picton's Division at Waterloo. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-78159-102-4.

- Joslen, H. F. (2003) [1960]. Orders of Battle: Second World War, 1939–1945. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-474-1.

- Kennedy, Alistair; Crabb, George Felix (1977). The Postal History of the British Army in World War I, Before and After, 1903–1929. Ewell, Surrey: G. Crabb. OCLC 60058343.

- Lord, Cliff; Watson, Graham (2003). The Royal Corps of Signals: Unit Histories of the Corps (1920–2001) and its Antecedents. West Midlands: Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-07-9.

- Mead, Richard (2007). Churchill's Lions: A Biographical Guide to the Key British Generals of World War II. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-431-0.

- Molony, .J.C; et al. (2004) [1973]. The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Campaign in Sicily 1943 and the Campaign in Italy 3rd September 1943 to 31 March 1944. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. V. London: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-069-6.

- Newbold, David John (1988). British Planning And Preparations To Resist Invasion on Land, September 1939 – September 1940 (PhD thesis). London: King's College London. OCLC 556820697.

- Oman, Charles (1930). A History of the Peninsular War. Vol. VII August 1813 – April 14, 1814. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 185228609.

- Pawley, Margaret (2007). The Watch on the Rhine: The Military Occupation of the Rhineland, 1918–1930. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-457-2.

- Place, Timothy Harrison (2000). Military Training in the British Army, 1940–1944. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-8091-0.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004) [1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. London: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-184574-068-9.

- Ross-of-Bladensburg, John Foster George (1896). A History of the Coldstream Guards from 1815 to 1895. London: A.D. Inness & Co. OCLC 1152610342 – via Gutenberg.org.

- Satre, Lowell J. (1976). "St. John Brodrick and Army Reform, 1901–1903". Journal of British Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 15 (2): 117–139. doi:10.1086/385688. JSTOR 175135. S2CID 154171561.

- Sheehan, Fred (1994). Anzio: Epic of Bravery. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2678-4.

- Siborne, William (1900). The Waterloo Campaign (5th ed.). Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co. OCLC 672639901.

- Smart, Nick (2005). Biographical Dictionary of British Generals of the Second World War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-036-6.

- Tanner, James (2014). The British Army since 2000. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-593-3.* * * Thompson, Julian (2009). Dunkirk: Retreat to Victory. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-33043-796-7.

- Veve, Thomas Dwight (1992). The Duke of Wellington and the British Army of Occupation in France, 1815-1818. Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-31327-941-6.

- Whitmarsh, Andrew (2007). "British Army Manoeuvres and the Development of Military Aviation, 1910–1913". War in History. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. 14 (3): 325–346. doi:10.1177/0968344507078378. JSTOR 26070710. S2CID 111294536.

- Zabecki, David T. (1999). World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8240-7029-8.

Further reading

External links

- Imperial War Museam. "Memorial: 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- War Memorials Online. "1st Division Porchway". War Memorials Online. Retrieved 27 June 2022.