Triplex locomotive

A triplex locomotive is a steam locomotive that divides the driving force on its wheels by using three pairs of cylinders to drive three sets of driving wheels. Any such locomotive will inevitably be articulated. All triplex locomotives built were of the Mallet type, but with an extra set of driving wheels under the tender. The concept was extended to locomotives with four, five or six sets of drive wheels. However, these locomotives were never built, except for one quadruplex locomotive in Belgium.

_(27197514215).jpg.webp)

Triplex classes

Baldwin Locomotive Works built three triplex locomotives for the Erie Railroad between 1914 and 1916.[1] The first was named Matt H. Shay, after a beloved employee of that road.[1] These Triplexes were given the classification of P-1 and they could reportedly pull 650 freight cars.[2] The triplexes were primarily used as pushers on grades requiring helper locomotives. Slow moving, the triplexes were not considered highly successful, and no more were built for Erie. The Erie Railroad scrapped their Triplexes from 1929, 1931, and 1933.[3]

Another very similar designed triplex was built by Baldwin as a 2-8-8-8-4 for the Virginian Railway, as No. 700, in 1916. This triplex was given classification of XA, so named due to the experimental nature of the locomotive. The 2-8-8-8-4 was considered unsuccessful because it only made a maximum speed of 4.8–8.0 km/h (3–5 mph) and had high maintenance costs. The XA was sent back to Baldwin Locomotive Works where it was taken apart in 1920 and converted into a 2-8-8-0 and a 2-8-2. These two engines were in service until 1953.[4] Neither of the two engines were preserved.

Design

The triplex locomotives were of the Mallet type, but with an extra set of driving wheels under the tender. The centre set of cylinders received high-pressure steam. The exhaust from these was fed to the two other sets of cylinders.[3] The right cylinder exhausted into the front set of low pressure cylinders, and the left into the rear set; this is also why the high pressure cylinders are the same diameter as the low pressure cylinders, making the engine a 2 to 1 compound, whereas most Mallet locomotives have much smaller high pressure cylinders. The front set exhausted through the smokebox and the rear set exhausted first through a feedwater heater in the tender and then through a large pipe directly to the outside, as can be seen in the photo. As only half of the exhaust steam went through the blast pipe in the smokebox, the draft in the firebox and the heating of the boiler was poor. Although the boiler was large in comparison with contemporary two-cylinder and four-cylinder locomotives, six large cylinders required more steam than even such a boiler could supply.[3]

The Erie locomotives always operated in compound mode and did not have starting valves that would have put full pressure on all six cylinders, yet the triplexes produced huge amounts of tractive effort that may have been the highest of any steam locomotives ever. Westing[3] gives a figure of 160,000 lbf (710 kN) in compound mode and seems to indicate that it was the largest tractive effort for any locomotives up to the mid-1910s. The Union Pacific Big Boy, built in the 1940s, did not exceed the tractive effort of the Erie locomotives either, as it had a tractive effort of only 135,375 lbf (602.18 kN).

The triplexes could also be considered the largest tank locomotives ever built, as the tender also had driving wheels and thus contributed to the traction. The problem of variable adhesion of the tender unit was not a serious one, as the pusher locomotives had frequent opportunities to take on additional fuel and water.

Usage

In all, only four triplex locomotives were built, and only in the United States. Because the tractive effort of the locomotives was so great that the couplings and frames of the cars could not withstand it,[5] the triplex locomotives could only be used to bank[3] heavy trains up steep grades. Even with their huge boilers, the Erie locomotives could only produce enough steam to run at 16 km/h (10 mph), the Virginian only 8.0 km/h (5 mph).[5] The reason for this was the poor performance of the boilers due to the lack of exhaust draught from the driving wheelset under the tender.[6]

The Erie locomotives were used as helpers on the Susquehanna Hill also known as the Gulf Summit, near Deposit, New York, on the Southern Tier Line. After 13 years they were replaced by 2-10-2s and retired.[5] All Erie triplex locomotives had been scraped by 1930, and none have survived.

The Virginian XA #700 2-8-8-8-4 was unsuccessful. It was returned to Baldwin, where it was rebuilt into a 2-8-2, numbered 410, and a 2-8-8-0, numbered 610. A two-wheel trailing truck was later added, making it into a 2-8-8-2. These two locomotives were operated until 1953.[5]

Expanding the concept

The concept of three drive wheel sets was extended to locomotive projects with four, five and six drive wheel sets. Only one of these projects, the Belgian quadruplex locomotive, was realised, while the others never got off the drawing board. However, while all of the triplex locomotives were Mallet locomotives, this concept was abandoned for the Belgian quadruplex locomotive and the quintuplex project originating from the same manufacturer. Beyer, Peacock and Company’s Super-Garratt project was again based on the Mallet concept, with the bridge of a Garratt locomotive on two Mallet bogies.

United States

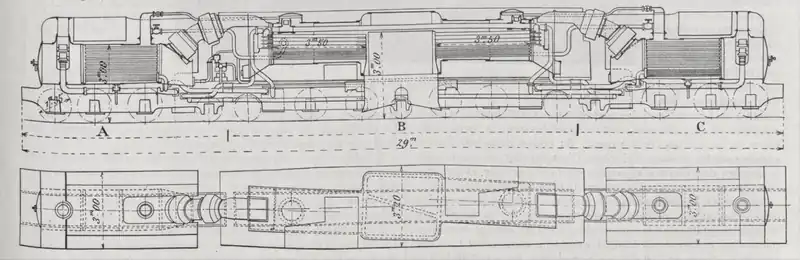

In June 1914, George R. Henderson was granted US Patent 1,100,563 for a quadruplex 2-8-8-8-8-2 locomotive,[7] which was assigned to the Baldwin Locomotive Company. Baldwin submitted the design to the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF), which in the 1910s was a strong proponent of compound locomotives.[8][9][10]

This would have been, in 1913, by far the largest steam locomotive ever proposed. In quadruplex form, it would have been 129 feet 10+1⁄2 inches (39.586 m) in overall length, total weight of about 885,000 pounds (401 t), with tractive effort of 200,000 pounds-force (890 kN).[11]

The Quadruplex was to comprise three articulated engines of 8 driving wheels each beneath the locomotive itself, and a fourth engine beneath the tender. As a compound locomotive, engine cylinders 7 and 9 (as numbered on the above image) would receive high pressure steam to drive the first and third engines, each would exhaust as low-pressure steam to power cylinders 8 and 10 on the second and fourth engines. Both sets of low-pressure cylinders would then exhaust direct to atmosphere through stacks 33 and 38. The drivers had a diameter of 60 in (1524 mm).[12]

Due mostly to its extreme length the design included a number of mostly untried innovations:

- An engineer’s cab (24) at the very front, as well as a fireman’s cab (23) behind the firebox (17). Communication between the cabs was proposed as cable- or rod-operated signalling devices, similar to the engine order telegraph used on steamships, and possibly a voice pipe

- A jointed boiler with a flexible coupling (16) allowing the boiler casing to flex laterally on track curves. Such an accordion joint was already in use on a 2-6-6-2 locomotive of the AT&SF.[12]

- Two separate boilers, served by the single firebox: The front boiler (21) to supply the front two engines, the rear boiler (20) to supply the rear two engines. Working pressure of the boiler would be 215 psi (15 bar).[12]

- A turbine-driven extractor fan (26) within the smokebox (25) was intended to maintain a constant draft through the flues of both boilers. This was because Henderson had calculated that a conventional blast pipe utilizing steam exhausted from the low-pressure cylinders would have been inadequate to provide a sufficient draft until the locomotive was in motion.

By the time the patent was granted, the experience of the existing triplexes and jointed-boiler locomotives had shown the shortcomings of these designs, and the quadruplex did not proceed to construction.[8]

Belgium

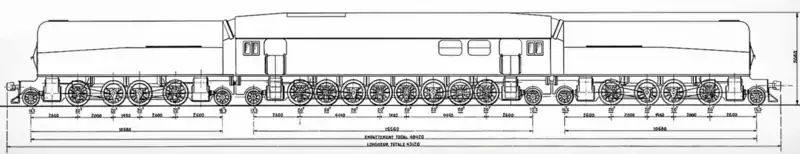

The only quadruplex locomotive built was No. 2096 for the National Railway Company of Belgium , built by the Ateliers Métallurgiques de Tubize in Belgium. It was also the first locomotive ever built with Franco-Crosti boilers. The locomotive consisted of three articulated sections with a total of four engines. The middle section, with two engines with four wheels each, carried the two steam boilers, which operated at 14 bar. They were arranged at a slight angle to allow the two fireboxes to be placed side by side in the centre.[13]

The two end units each carried a Franko-Crosti flue gas preheater. The connections between the boilers in the centre section and the preheaters in the end sections were expected to have problems with outside air being drawn in by leakage, so the spherical connections were designed with labyrinth seals.[14]

The water tanks were also in the end sections, which were driven by six-wheel engines. All engines were single-expansion engines. The 20 drivers were supplemented by 10 idlers. The total weight of the three-part locomotive was given as 230 t (according to other sources 248 t), the adhesion mass as 164 t.[13]

In the middle section were two identically cabs, which were used depending on the direction of travel, as the 29 m (31 maccording to other sources) long locomotive could not use turntables due to its length. Each of the two boilers had its own coal box and was operated by its own fireman. The coal boxes were located to the side of the long boilers. While one fireman could communicate directly with the driver, the other fireman's line of sight to the driver was blocked by the coal box, so communication was by audible signals only.[13]

The locomotive was delivered in 1932, but was never actually used. The locomotive's tractive forces were so high that the chain couplers broke. The reason for building the locomotive is unclear, as it was far beyond the needs of the Belgian State Railways for freight transport, and could not be used for passenger transport due to its low top speed of 60 kph. The sheer size of the locomotives caused problems with stabling, the large number of coupling wheels, cylinders and seals on the movable connections between the preheaters and the main boilers were additional maintenance problems, apart from the fact that the locomotive required two firemen instead of one. The locomotive was exhibited at the 1935 Brussels World's Fair and was retired shortly afterwards. Some believe that the locomotive was built as a proof of concept for the project of a larger hexaplex locomotive with the same body for the Russian market.[15]

Super-Garratt

Beyer, Peacock and Company also applied for a patent for a quadruplex locomotive in 1927. Based on their successful Garratt locomotive design, it was called the Super-Garratt. The standard gauge locomotive was designed as an articulated 2-6-6-2 + 2-6-6-2 for the North American railroads and would have been built in conjunction with the American Locomotive Company (ALCo).[16] The starting tractive force of 200,000 pounds-force (890 kN) of the 460-ton locomotive would probably have been at the limit of the couplers in use at the time. Like a Garratt locomotive, it had a centre frame with boiler, firebox and cab, which sat on two subframes at each end. Each subframe, like a Mallett locomotive, contained a fixed set of driving wheels and, at the end of the locomotive, a pivoting bogie with another set of driving wheels. In addition to the standard gauge version, a 3 ft 6 in gauge version was planned for the South African Railways (SAR), but neither version was built.[17][18]

Quintuplex

A quintuplex version (2-8-8-8-8-8-2) was also included in the George R. Henderson’s patent application for the quaruplex version. The design was based on the quadruplex, with the fourth and fifth engines under an extended, articulated tender.[9][10][19]

An even larger 2-10-10-10-10-10-2 variant appeared as an artist's impression in the August 1951 issue of Trains magazine. However, this idea seems to be speculative on the part of both the magazine writer and the artist, perhaps because AT&SF already had a fleet of 2-10-10-2’s in 1913. There is no evidence that either George Henderson or Baldwin suggested such a version.

Hexaplex

There was a Belgian project for a hexaplex locomotive for the Russian market, based on the Franco-Crosti quadruplex locomotive built for the Belgian State Railways. It had the wheel arrangement 2-4-4-2 + 2-8-8-2 + 2-4-4-2 and made full use of the Russian loading gauge and broad gauge. The total weight of the 43-metre-long locomotive was to be 410 tonnes, of which about 320 tonnes would have been available for adhesion. The water tank capacity was to be 60 m3, the coal capacity 15 tonnes.[14]

References

- Westing (1966), pp. 124–125.

- "A titan of the rails". The Independent. July 27, 1914. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Westing 1966, pp. 124–125.

- "2-8-8-8-2/4 "Triplex" Locomotives in the USA". www.steamlocomotive.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24.

- "2-8-8-8-2/4 "Triplex" Locomotives in the USA". steamlocomotive.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- M.T.H. Electric Trains (ed.). "HO 2-8-8-8-2 Triplex". Modèles Européens 2011 (in French). Columbia (MD): 11. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- US patent 1100563, Henderson, George, "Locomotive", issued 1914-06-16, assigned to Baldwin Locomotive Works

- "The Quadraplexes". www.douglas-self.com. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Solomon, Brian, 2015. The Majesty of Big Steam. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0760348925

- Drury, George H. (1993). Guide to North American Steam Locomotives. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing Company.

- ”What Might Have Been”, Trains magazine, August 1951

- "Baldwin Locomotive Works Design a Quadruplex Compound Locomotive". Railway an Locomotive Engineering. 28 (9): 320. September 1915.

- Valenziani, M.H (1933-03-25). "Nouveau type de locomotive à vapeur articulée à grande puisasance, système Franco". Le Génie civil (in French): 287.

- Self, Douglas. "The Franco-Crosti Boiler System". Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- Belgium's completely overkill engine - Quadraplex on YouTube

- Hills, Richard Leslie (1982). Beyer, Peacock : locomotive builders to the world. p. 182.

- Leslie Paxton and David Bourne, Locomotive of the South African Railways, Struik, 1985, pp. 8–9.

- Self, Douglas. "Dreams of Quadraplexes".

- Trains. Kalmbach Publishing Company. 1950.

Bibliography

- US 1629369 "Triple-expansion mallet locomotive." by Samuel M. Vauclain assigned to the Baldwin Locomotive Works filed on November 25, 1925

- Westing, Frederick (1966), The locomotives that Baldwin built. Containing a complete facsimile of the original "History of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1923", Crown Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-517-36167-2, LCCN 66025422.

.jpg.webp)

.gif)