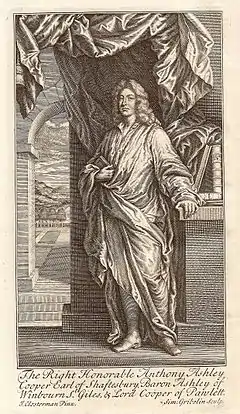

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (26 February 1671 – 16 February 1713) was an English peer, Whig politician, philosopher and writer.

The Earl of Shaftesbury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 February 1671 London, England |

| Died | 16 February 1713 (aged 41–42) Chiaia,Naples |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy Early modern philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Cambridge Platonism |

Early life

He was born at Exeter House in London, the son of the future Anthony Ashley Cooper, 2nd Earl of Shaftesbury and his wife Lady Dorothy Manners, daughter of John Manners, 8th Earl of Rutland. Letters sent to his parents reveal emotional manipulation attempted by his mother in refusing to see her son unless he cut off all ties to his father. At the age of three Ashley-Cooper was made over to the formal guardianship of his grandfather Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury. John Locke, as medical attendant to the Ashley household, was entrusted with the supervision of his education. It was conducted according to the principles of Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), and the method of teaching Latin and Greek conversationally was pursued by his instructress, Elizabeth Birch. At the age of eleven, it is said, Ashley could read both languages with ease.[1] Birch had moved to Clapham and Ashley spent some years there with her.[2]

In 1683, after the death of the first Earl, his father sent Lord Ashley, as he now was by courtesy, to Winchester College. Under a Scottish tutor, Daniel Denoune, he began a continental tour with two older companions, Sir John Cropley, 2nd Baronet, and Thomas Sclater Bacon.[3]

Under William and Mary

After the Glorious Revolution, Lord Ashley returned to England in 1689. It took five years, but he entered public life, as a parliamentary candidate for the borough of Poole, and was returned on 21 May 1695. He spoke for the Bill for Regulating Trials in Cases of Treason, one provision of which was that a person indicted for treason or misprision of treason should be allowed the assistance of counsel.[1]

Although a Whig, Ashley was not partisan. His poor health forced him to retire from parliament at the dissolution of July 1698. He suffered from asthma.[1] The following year, to escape the London environment, he purchased a property in Little Chelsea,[3] adding a 50-foot extension to the existing building to house his bedchamber and Library, and planting fruit trees and vines. He sold the property to Narcissus Luttrell in 1710.[4]

Lord Ashley moved to the Netherlands. Away for over a year, Ashley returned to England, and shortly succeeded his father as Earl of Shaftesbury. He took an active part, on the Whig side in the House of Lords, in the general election of 1700–1701, and again, with more success, in the autumn election of 1701.[3]

Under Queen Anne

After the first few weeks of Anne's reign, Shaftesbury, who had been deprived of the vice-admiralty of Dorset, returned to private life.[1] In August 1703, he again settled in the Netherlands. At Rotterdam he lived, he says in a letter to his steward Wheelock, at the rate of less than £200 a year, and yet had much to dispose of and spend beyond convenient living.[5]

Shaftesbury returned to England in August 1704, he landed at Aldeburgh, Suffolk having escaped a dangerous storm during his voyage.[6] He had symptoms of consumption, and gradually became an invalid. He continued to take an interest in politics, both home and foreign, and supported England's participation in the War of the Spanish Succession.[5]

The declining state of Shaftesbury's health rendered it necessary for him to seek a warmer climate and in July 1711 he set out for Italy. He settled at Naples in November, and lived there for more than a year.[7]

Death

Shaftesbury died at Chiaia in the Kingdom of Naples, on 15 February 1713 (N.S.) His body was brought back to England and buried at Wimborne St Giles, the family seat in Dorset.[3]

Associations

John Toland was an early associate, but Shaftesbury after some time found him a troublesome ally. Toland published a draft of the Inquiry concerning Virtue, without permission. Shaftesbury may have exaggerated its faults, but the relationship cooled.[3] Toland edited 14 letters from Shaftesbury to Robert Molesworth, published in Toland in 1721.[7] Molesworth had been a good friend from the 1690s. Other friends among English Whigs were Charles Davenant, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, Walter Moyle, William Stephens and John Trenchard.[3]

From Locke's circle in England, Shaftesbury knew Edward Clarke, Damaris Masham and Walter Yonge. In the Netherlands in the late 1690s, he got to know Locke's contact Benjamin Furly. Through Furly he had introductions to become acquainted with Pierre Bayle, Jean Leclerc and Philipp van Limborch. Bayle introduced him to Pierre Des Maizeaux.[3] Letters from Shaftesbury to Benjamin Furly, his two sons, and his clerk Harry Wilkinson, were included in a volume entitled Original Letters of Locke, Sidney and Shaftesbury, published by Thomas Ignatius Maria Forster (1830, and in enlarged form, 1847).

Shaftesbury was a patron of Michael Ainsworth, a young Dorset man of Wimborne St Giles, maintained by Shaftesbury at University College, Oxford. The Letters to a Young Man at the University (1716) were addressed to Ainsworth. Others he supported included Pierre Coste and Paul Crellius.[3]

Works

Most of the works for which Shaftesbury is known were completed in the period 1705 to 1710. He collected a number of those and other works in Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times (first edition 1711, anonymous, 3 vols.).[8][9] His philosophical work was limited to ethics, religion, and aesthetics where he highlighted the concept of the sublime as an aesthetic quality.[7] Basil Willey wrote "[...] his writings, though suave and polished, lack distinction of style [...]".[10]

Contents of the Characteristicks

This listing refers to the first edition.[11] The later editions saw changes. The Letter on Design was first published in the edition of the Characteristicks issued in 1732.[7]

- Volume I

The opening piece is A Letter Concerning Enthusiasm, advocating religious toleration, published anonymously in 1708. It was based on a letter sent to John Somers, 1st Baron Somers of September 1707.[12] At this time repression of the French Camisards was topical.[7] The second treatise is Sensus Communis: An Essay on the Freedom of Wit and Humour, first published in 1709.[8][13] The third part is Soliloquy: or, Advice to an Author, from 1710.[14]

- Volume II

It opens with Inquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit, based on a work from 1699. With this treatise, Shaftesbury became the founder of moral sense theory.[8][15] It is accompanied by The Moralists, a Philosophical Rhapsody, from 1709.[8] Shaftesbury himself regarded it as the most ambitious of his treatises.[16] The main object of The Moralists is to propound a system of natural theology, for theodicy. Shaftesbury believed in one God whose characteristic attribute is universal benevolence; in the moral government of the universe; and in a future state of man making up for the present life.[7]

- Volume III

Entitled Miscellaneous Reflections, this consisted of previously unpublished works.[8] From his stay at Naples there was A Notion of the Historical Draught or Tablature of the Judgment of Hercules.[7]

Philosophical moralist

Shaftesbury as a moralist opposed Thomas Hobbes. He was a follower of the Cambridge Platonists, and like them rejected the way Hobbes collapsed moral issues into expediency.[17] His first published work was an anonymous Preface to the sermons of Benjamin Whichcote, a prominent Cambridge Platonist, published in 1698. In it he belaboured Hobbes and his ethical egoism, but also the commonplace carrot and stick arguments of Christian moralists.[3] While Shaftesbury conformed in public to the Church of England, his private view of some of its doctrines was less respectful.[7]

His starting point in the Characteristicks, however, was indeed such a form of ethical naturalism as was common ground for Hobbes, Bernard Mandeville and Spinoza: appeal to self-interest. He divided moralists into Stoics and Epicurean, identifying with the Stoics and their attention to the common good. It made him concentrate on virtue. He took Spinoza and Descartes as the leading Epicureans of his time (in unpublished writings).[18]

Shaftesbury examined man first as a unit in himself, and secondly socially. His major principle was harmony or balance, rather than rationalism. In man, he wrote,

"Whoever is in the least versed in this moral kind of architecture will find the inward fabric so adjusted, [...] that the barely extending of a single passion too far or the continuance [...] of it too long, is able to bring irrecoverable ruin and misery".[19]

This version of a golden mean doctrine that goes back to Aristotle was savaged by Mandeville, who slurred it as associated with a sheltered and comfortable life, Catholic asceticism, and modern sentimental rusticity.[20] On the other hand, Jonathan Edwards adopted Shaftesbury's view that "all excellency is harmony, symmetry or proportion".[21]

On man as a social creature, Shaftesbury argued that the egoist and the extreme altruist are both imperfect. People, to contribute to the happiness of the whole, must fit in.[22] He rejected the idea that humankind is naturally selfish; and the idea that altruism necessarily cuts across self-interest.[23] Thomas Jefferson found this general and social approach attractive.[24]

This move relied on a close parallel between moral and aesthetic criteria. In the English tradition, this appeal to a moral sense was innovative. Primarily emotional and non-reflective, it becomes rationalised by education and use. Corollaries are that morality stands apart from theology, and the moral qualities of actions are determined apart from the will of God; and that the moralist is not concerned to solve the problems of free will and determinism. Shaftesbury in this way opposed also what is to be found in Locke.[22]

Reception

The conceptual framework used by Shaftesbury was representative of much thinking in the early Enlightenment, and remained popular until the 1770s.[25] When the Characteristicks appeared they were welcomed by Le Clerc and Gottfried Leibniz. Among the English deists Shaftesbury was significant, plausible and the most respectable. [22]

By the Augustans

In terms of Augustan literature, Shaftesbury's defence of ridicule was taken as an entitlement to scoff, and to use ridicule as a "test of truth". Clerical authors operated on the assumption that he was a freethinker.[26] Ezra Stiles, reading Characteristicks in 1748 without realising Shaftesbury had been marked down as a deist, was both impressed and sometimes shocked. Around this time John Leland and Philip Skelton stepped up a campaign against deist influence, tarnishing Shaftesbury's reputation.[27]

While Shaftesbury wrote on ridicule in the 1712 edition of Characteristicks, the modern scholarly consensus is that the uses of his views on it as a "test of truth" were a stretch.[28] According to Alfred Owen Aldridge, the "test of truth" phrase is not to be found in Characteristicks; it was imposed on the Augustan debate by George Berkeley.[29]

The influence of Shaftesbury, and in particular The Moralists, on An Essay on Man, was claimed in the 18th century by Voltaire (in his philosophical letter "On Pope"),[30] Lord Hervey and Thomas Warton, and supported in recent times, for example by Maynard Mack. Alexander Pope did not mention Shaftesbury explicitly as a source: this omission has been understood in terms of the political divide, Pope being a Tory.[31] Pope references the character Theocles from The Moralists in the Dunciad (IV.487–490):

"Or that bright Image to our Fancy draw,

Which Theocles in raptur'd vision saw,

While thro' Poetic scenes the Genius roves,

Or wanders wild in Academic Groves".

In notes to these lines, Pope directed the reader to various passages in Shaftesbury's work.[22]

In moral philosophy and its literary reflection

Shaftesbury's ethical system was rationalised by Francis Hutcheson, and from him passed with modifications to David Hume; these writers, however, changed from reliance on moral sense to the deontological ethics of moral obligation.[32] From there it was taken up by Adam Smith, who elaborated a theory of moral judgement with some restricted emotional input, and a complex apparatus taking context into account.[33] Joseph Butler adopted the system, but not ruling out the place of "moral reason", a rationalist version of the affective moral sense.[34] Samuel Johnson, the American educator, did not accept Shaftesbury's moral sense as a given, but believed it might be available by intermittent divine intervention.[35]

In the English sentimental novel of the 18th century, arguments from the Shaftesbury–Hutcheson tradition appear. An early example in Mary Collyer's Felicia to Charlotte (vol.1, 1744) comes from its hero Lucius, who reasons in line with An Enquiry Concerning Virtue and Merit on the "moral sense".[36] The second volume (1749) has discussions of conduct book material, and makes use of the Philemon to Hydaspes (1737) of Henry Coventry, described by Aldridge as "filled with favorable references to Shaftesbury."[37][38] The eponymous hero of The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753) by Samuel Richardson has been described as embodying the "Shaftesburian model" of masculinity: he is "stoic, rational, in control, yet sympathetic towards others, particularly those less fortunate."[39] A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1768) by Laurence Sterne was intended by its author to evoke the "sympathizing principle" on which the tradition founded by latitudinarians, Cambridge Platonists and Shaftesbury relied.[40]

Across Europe

In 1745 Denis Diderot adapted or reproduced the Inquiry concerning Virtue in what was afterwards known as his Essai sur le Mérite et la Vertu. In 1769 a French translation of the whole of Shaftesbury's works, including the Letters, was published at Geneva.[22]

Translations of separate treatises into German began to be made in 1738, and in 1776–1779 there appeared a complete German translation of the Characteristicks. Hermann Theodor Hettner stated that not only Leibniz, Voltaire and Diderot, but Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Moses Mendelssohn, Christoph Martin Wieland and Johann Gottfried von Herder, drew from Shaftesbury.[22]

Herder in early work took from Shaftesbury arguments for respecting individuality, and against system and universal psychology. He went on to praise him in Adrastea.[41] Wilhelm von Humboldt found in Shaftesbury the "inward form" concept, key for education in the approach of German classical philosophy.[42] Later philosophical writers in German (Gideon Spicker with Die Philosophie des Grafen von Shaftesbury, 1872, and Georg von Gizycki with Die Philosophie Shaftesbury's, 1876) returned to Shaftesbury in books.[43]

Legacy

At the beginning of the 18th century, Shaftesbury built a folly on the Shaftesbury Estate, known as the Philosopher's Tower. It sits in a field, visible from the B3078 just south of Cranborne.

In the Shaftesbury papers that went to the Public Record Office are several memoranda, letters, rough drafts, etc.[7]

A portrait of the 3rd Earl is displayed in Shaftesbury Town Hall.[44]

Family

Shaftesbury married in 1709 Jane Ewer, the daughter of Thomas Ewer of Bushey Hall, Hertfordshire. On 9 February 1711, their only child Anthony, the future fourth Earl was born.[3]

His son succeeded him in his titles and republished Characteristicks in 1732. His great-grandson was the famous philanthropist, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury.[7]

Notes

- Fowler & Mitchell 1911, p. 763.

- "About". The Clapham Historian. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Klein, Lawrence E. "Cooper, Anthony Ashley, third Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6209. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- The Environs of London: Being an Historical Account of the Towns, Villages, and Hamlets, Within Twelve Miles of that Capital : Interspersed with Biographical Anecdotes. T. Cadell and W. Davies. 1811. pp. 110–111.

- Fowler & Mitchell 1911, pp. 763, 764.

- "Electronic Enlightenment: John Freke to John Locke". www.e-enlightenment.com. 2019. doi:10.13051/ee:doc/lockjoou0080384b1c. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Fowler & Mitchell 1911, p. 764.

- "Lord Shaftesbury [Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury"] entry by Michael B. Gill in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 9 September 2016

- Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper of (1711). Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. s.n.

- Willey, Basil (1964). The English Moralists. Chatto & Windus. p. 227.

- Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper of (1711). Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. s.n.

- Richard B. Wolf, The Publication of Shaftesbury's "Letter concerning Enthusiasm", Studies in Bibliography Vol. 32 (1979), pp. 236–241, at pp. 236–237. Published by: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia JSTOR 40371706

- Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper of (1711). Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. s.n. p. 57.

- Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper of (1711). Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. s.n. p. 151.

- "Anthony Ashley Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury, on the Emotions" entry by Amy M. Schmitter in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2010

- John G. Hayman, The Evolution of "The Moralists", The Modern Language Review Vol. 64, No. 4 (Oct., 1969), pp. 728–733, at p. 728. Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association JSTOR 3723913

- Brett, R. L. (2020). The Third Earl of Shaftesbury: A Study in Eighteenth-Century Literary Theory. Routledge. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-000-03127-0.

- Israel, Jonathan I. (2002). Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750. OUP Oxford. pp. 625–626. ISBN 9780191622878.

- Fowler & Mitchell 1911, p. 765 Cites: Inquiry concerning Virtue or Merit, Bk. II. ii. 1.

- Sambrook, James (2014). The Eighteenth Century: The Intellectual and Cultural Context of English Literature 1700–1789. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-317-89324-0.

- Bombaro, John J. (2011). Jonathan Edwards's Vision of Reality: The Relationship of God to the World, Redemption History, and the Reprobate. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-63087-812-2.

- Fowler & Mitchell 1911, p. 765.

- Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper Earl of (1977). An Inquiry Concerning Virtue, Or Merit. Manchester University Press. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-7190-0657-9.

- Vicchio, Stephen J. (2007). Jefferson's Religion. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-59752-830-6.

- Chisick, Harvey (2005). Historical Dictionary of the Enlightenment. Scarecrow Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-8108-6548-8.

- Bullard, Paddy (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Eighteenth-Century Satire. Oxford University Press. p. 578. ISBN 978-0-19-872783-5.

- Fiering, Norman (2006). Jonathan Edwards's Moral Thought and Its British Context. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 109 note8. ISBN 978-1-59752-618-0.

- Amir, Lydia B. (2014). Humor and the Good Life in Modern Philosophy: Shaftesbury, Hamann, Kierkegaard. SUNY Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4384-4938-8.

- Alfred Owen Aldridge, Shaftesbury and the Test of Truth, PMLA Vol. 60, No. 1 (Mar., 1945), pp. 129–156, at p. 129. Published by: Modern Language Association JSTOR 459126

- "On Pope"

- William E. Alderman, Pope's "Essay on Man" and Shaftesbury's "The Moralists", The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America Vol. 67, No. 2 (Second Quarter, 1973), pp. 131–140. Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Bibliographical Society of America JSTOR 24301749

- Darwall, Stephen; Stephen, Darwall (1995). The British Moralists and the Internal 'Ought': 1640–1740. Cambridge University Press. p. 219 and note 25. ISBN 978-0-521-45782-8.

- Haakonssen, Knud (1996). Natural Law and Moral Philosophy: From Grotius to the Scottish Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-521-49802-9.

- Skorupski, John (2010). The Routledge Companion to Ethics. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-136-96422-0.

- Joseph J. Ellis III, The Philosophy of Samuel Johnson, The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan., 1971), pp. 26–45, at p. 44. Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture JSTOR 1925118

- Staves, Susan (2006). A Literary History of Women's Writing in Britain, 1660–1789. Cambridge University Press. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-1-139-45858-0.

- Staves, Susan (2006). A Literary History of Women's Writing in Britain, 1660–1789. Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-139-45858-0.

- Alfred Owen Aldridge, Shaftesbury and the Deist Manifesto, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society Vol. 41, No. 2 (1951), pp. 297–382, at p. 376. Published by: American Philosophical Society. JSTOR 1005651

- Sabor, Peter; Schellenberg, Betty A. (2017). Samuel Richardson in Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-108-32716-9.

- Ross, Ian Campbell (2001). Laurence Sterne: A Life. Oxford University Press. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-19-212235-3.

- Gjesdal, Kristin (2017). Herder's Hermeneutics: History, Poetry, Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. p. 112 and note 27. ISBN 978-1-107-11286-5.

- Palmer, Joy; Bresler, Liora; Cooper, David (2002). Fifty Major Thinkers on Education: From Confucius to Dewey. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-134-73594-5.

- Erdmann, Johann Eduard (2004). A History of Philosophy. Psychology Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-415-29542-0.

- "Anthony Ashley-Cooper (1671–1713), 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury". Art UK. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Fowler, Thomas; Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). "Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 763–765.

Further reading

- Cooper, Anthony Ashley, Earl of Shaftesbury, An Inquiry Concerning Virtue, London, 1699. Facsimile ed., introd. Joseph Filonowicz, 1991, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, ISBN 978-0-8201-1455-2.

- David Walford (editor). An Inquiry Concerning Virtue or Merit. A selection of material from Toland's 1699 edition with introduction.

- Robert B. Voitle, The third Earl of Shaftesbury, 1671–1713, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, c. 1984.

- Edward Chaney (2000), George Berkeley's Grand Tours: The Immaterialist as Connoisseur of Art and Architecture, in E. Chaney, The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed. London, Routledge

- Watson, Paula; Lancaster, Henry. "ASHLEY, Anthony, Lord Ashley (1671–1713), of Wimborne St. Giles, Dorset". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- Smith, George H. (2008). "Shaftesbury, Third Earl of (1671–1713)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. p. 462. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n282. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

External links

Works by or about Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury at Wikisource

Works by or about Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury at Wikisource Quotations related to Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury at Wikiquote- Shaftesbury's Characteristicks in three parts

- Contains the five treatises in Shaftesbury's Characteristicks, slightly modified for easier reading

- The Third Earl of Shaftesbury, an article by John McAteer in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2011