4-Hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase

4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (EC 1.14.14.9) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

- 4-hydroxyphenylacetate + FADH2 + O2 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate + FAD + H2O

| 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

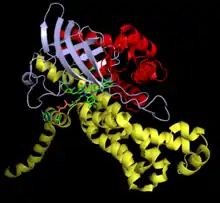

PyMOL-generated cartoon of a Thermus thermophilus hpaB monomer complexed to FAD and 4-hydroxyphenylacetate. Color-coding distinguishes the enzyme's three primary structural domains.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.14.14.9 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 37256-71-6 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

This reaction is the first step in a pathway found in enteric bacteria such as Escherichia coli and soil bacteria such as Pseudomonas putida which degrades 4-hydroxyphenylacetate (4-HPA), allowing these bacteria to use 4-HPA and other aromatic compounds found in mammalian digestive tracts or in soil as a carbon source.[2] While most known flavin monooxygenases use NADH or NADPH as substrates (and use the flavins FAD or FMN as prosthetic groups [3]), this enzyme is part of a two-component system, in which a flavin oxidoreductase partner (EC 1.5.1.37) regenerates FADH2 by oxidizing NADH to NAD+. hpaB and hpaC, the 4-HPA oxygenase and reductase partner proteins (respectively) of E. coli strain W, were the first two-component flavin monoxygenase system identified.[4] While known examples of this enzyme share a common catalytic mechanism and likely evolutionary origin, they differ with respect to regulation and ability to substitute FMNH2 for FADH2 as a substrate.

Structure

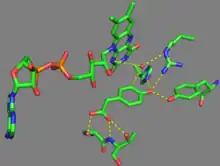

This enzyme is a tetramer which forms as a dimer of dimers.[1] Sequence alignments of the Thermus thermophilus and E. coli hpaB enzymes show structural similarity to each other and to the oxygenase components of other bacterial two-component monooxygenases for compounds such as phenol and chlorophenol.[1] Each monomer of this protein consists of an N-terminal alpha-helical domain, a middle beta barrel domain, and a C-terminal "tail" helix. FADH2 is bound by a groove between these domains; this binding event causes a loop in the middle domain to change position, preforming a binding site for 4-HPA. At this point, multiple residues act to stabilize catalytic intermediates by hydrogen-bonding to the peroxide bound to FAD, as well as to the hydroxyl group of 4-HPA's phenol moiety (stabilizing its dienone transition state - see Mechanism). The loop which moves to form the 4-HPA binding site when FADH2 binds provides catalytic specificity by hydrogen-bonding to 4-HPA's carboxylic acid moiety.[1]

Mechanism

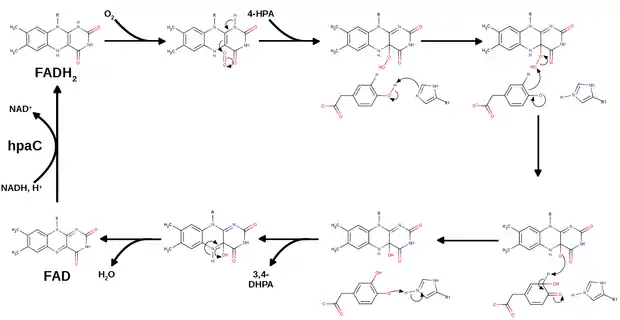

While many flavin-dependent monooxygenases retain FMN or FAD in their active sites throughout their catalytic cycle,[3] this enzyme binds FADH2 at the start of its catalytic cycle and releases FAD at the end. After FADH2 binds, dioxygen attacks it at the C4a carbon, leading to a C4a-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate. 4-HPA then binds, and a conformational change sequesters the enzyme's active site from solution, preventing the oxygen from escaping as toxic hydrogen peroxide. 4-HPA is then hydroxylated via a dienone intermediate and released as 3,4-DHPA; with the peroxide bond broken, C4a-hydroxyflavin releases the remaining oxygen atom by eliminating water and is released from the enzyme as FAD.[1]

Biological Function

To cope with the wide variety of phenolic compounds found in nature, bacterial pathways for degradation of aromatic compounds generally begin by channeling these diverse substrates towards a few common intermediates, which are then further degraded.[5] Pathways for catabolizing aromatic compounds generally begin by adding two hydroxyl groups to the benzene ring, most often on adjacent carbons. This product then undergoes ring cleavage to produce a linear molecule which is ultimately degraded to intermediates of central metabolism, such as succinate, pyruvate, and carbon dioxide. In the case of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate, which only needs one hydroxyl group to be added, a monooxygenase is required.

Among common E. coli laboratory strains, the 4-HPA degradation pathway is not found in the commonly used K-12 strain, but it does appear in strains B, C, and W (the strain in which most research into the pathway has been done). Only strains containing this pathway are able to survive by metabolizing 4-HPA as the sole carbon source, showing that this pathway is required for catabolism of this compound, and likely for similar phenolic compounds as well.[6]

Evolution

In addition to the exclusively FADH2-dependent monooxygenase found in species such as E. coli and T. thermophilus, a version of the enzyme which can use either reduced FAD or reduced FMN has been described in Acinetobacter baumannii.[7] Although these enzymes catalyze similar reactions and share a similar acyl-CoA dehydrogenase fold, the FMN-dependent enzyme is allosterically regulated by 4-HPA while the FADH2-dependent enzyme is likely regulated by a simpler kinetic mechanism, in which low concentrations of 4-HPA lead the enzyme to bind and sequester FADH2 as part of the normal catalytic cycle, causing the free concentration of FADH2 to drop until the flavin oxidoreductase's reaction is indirectly inhibited as well.[8] Along with other differences in regulation and substrate binding despite a shared fundamental catalytic mechanism,[9] this has led to speculation that these enzymes collectively represent an example of convergent evolution.[3]

Potential Applications

In addition to 4-HPA, the enzyme has been reported to have activity on a number of other phenolic substrates.[4] Metabolic engineers have demonstrated that microbes expressing the E. coli enzyme can catalyze reactions such as hydroxylation of tyrosine to L-dopa[10] and hydroxylation of the pharmacologically interesting phenylpropanoids umbelliferone and resveratrol.[11] However, these approaches are not currently used commercially.

References

- Kim SH, Hisano T, Takeda K, Iwasaki W, Ebihara A, Miki K (November 2007). "Crystal structure of the oxygenase component (HpaB) of the 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase from Thermus thermophilus HB8". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (45): 33107–17. doi:10.1074/jbc.m703440200. PMID 17804419.

- Díaz E, Ferrández A, Prieto MA, García JL (December 2001). "Biodegradation of aromatic compounds by Escherichia coli". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 65 (4): 523–69, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.65.4.523-569.2001. PMC 99040. PMID 11729263.

- Huijbers MM, Montersino S, Westphal AH, Tischler D, van Berkel WJ (February 2014). "Flavin dependent monooxygenases". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 544: 2–17. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.005. PMID 24361254.

- Prieto MA, Perez-Aranda A, Garcia JL (April 1993). "Characterization of an Escherichia coli aromatic hydroxylase with a broad substrate range". Journal of Bacteriology. 175 (7): 2162–7. doi:10.1128/jb.175.7.2162-2167.1993. PMC 204336. PMID 8458860.

- Helmut Sigel; Astrid Sigel (25 March 1992). Metal Ions in Biological Systems: Volume 28: Degradation of Environmental Pollutants by Microorganisms and Their Metalloenzymes. CRC Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-8247-8639-7.

- Burlingame R, Chapman PJ (July 1983). "Catabolism of phenylpropionic acid and its 3-hydroxy derivative by Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology. 155 (1): 113–21. doi:10.1128/JB.155.1.113-121.1983. PMC 217659. PMID 6345502.

- Alfieri A, Fersini F, Ruangchan N, Prongjit M, Chaiyen P, Mattevi A (January 2007). "Structure of the monooxygenase component of a two-component flavoprotein monooxygenase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (4): 1177–82. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.1177A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608381104. PMC 1783134. PMID 17227849.

- Louie TM, Xie XS, Xun L (June 2003). "Coordinated production and utilization of FADH2 by NAD(P)H-flavin oxidoreductase and 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase". Biochemistry. 42 (24): 7509–17. doi:10.1021/bi034092r. PMID 12809507.

- Chakraborty S, Ortiz-Maldonado M, Entsch B, Ballou DP (January 2010). "Studies on the mechanism of p-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-hydroxylase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a system composed of a small flavin reductase and a large flavin-dependent oxygenase". Biochemistry. 49 (2): 372–85. doi:10.1021/bi901454u. PMC 2806516. PMID 20000468.

- US application 2006141587, Kramer, M; Kremer-Muschen, S & Wubbolts, MG, "Process for the preparation of L-3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine by aerobic fermentation of a microorganism", published 2006-06-29

- Lin Y, Yan Y (September 2014). "Biotechnological production of plant-specific hydroxylated phenylpropanoids". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 111 (9): 1895–9. doi:10.1002/bit.25237. PMID 24752627.