Dorset Militia

The Dorset Militia was an auxiliary[lower-alpha 1] military force in the county of Dorsetshire[lower-alpha 2] in South West England. From their formal organisation as Trained Bands in 1558 until their final service as the Special Reserve, the Militia regiments of the county carried out internal security and home defence duties. They saw active service during the Second Bishops' War and the English Civil War, and played a prominent part in suppressing the Monmouth Rebellion. After being the first English militia regiment to reform in 1758, they served in home defence in all of Britain's major wars, including service in Ireland, and finally trained thousands of reinforcements during World War I. After a shadowy postwar existence they were formally disbanded in 1953.

| Dorset Militia 3rd Battalion, Dorset Regiment | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1558–1953 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Battalion |

| Garrison/HQ | The Keep, Dorchester |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Thomas Strangways George Pitt, 1st Baron Rivers Edward Digby, 2nd Earl Digby |

Early history

The English militia was descended from the Anglo-Saxon Fyrd, the military force raised from the freemen of the shires under command of their Sheriff. It continued under the Norman kings, and was reorganised under the Assizes of Arms of 1181 and 1252, and again by King Edward I's Statute of Winchester of 1285.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

In 1296 Edward called out the horse and foot of Dorset and Somerset to defend their shires from the French while he was away campaigning in Scotland. In February 1322 John de Bello Campo was ordered to raise all the horse and foot of Dorset and Somerset against the Baronial rebels. A week later Ralph de Gorges and Sir John de Clyveden were ordered to raise 1000 footmen (later increased to 2000) from Somerset and Dorset for service against invading Scots and the rebels, for the campaign that culminated in the Battle of Boroughbridge. Again, in 1326 Dorset and Somerset were ordered to levy 3000 archers, light cavalry and others for the defence of the realm. For King Edward III's 1333 campaign against the Scots, Bello Campo was instructed to levy 500 archers from Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire. By now the infantry were mainly equipped with the English longbow. The usual shire contingent was divided into companies of roughly 100 men commanded by ductores or constables, and subdivided into platoons of 20 led by vintenars. For Edward III's summer campaign in Scotland in 1335 Dorset supplied a 'ductor' with 59 mounted archers.[9][10][11]

In 1539 King Henry VIII, fearing invasion, held a Great Muster of all the counties, recording the number of armed men available in each hundred, borough or liberty (such as the Isle of Portland in Dorset). Dorsetshire supplied 5245 names, but with no details of how they were armed.[4][12]

Dorset Trained Bands

The legal basis of the militia was updated by two Acts of 1557 covering musters and the maintenance of horses and armour. The county militia was now under the Lord Lieutenant, assisted by the Deputy Lieutenants (DLs) and Justices of the Peace (JPs). The entry into force of these Acts in 1558 is seen as the starting date for the organised county militia in England. Although the militia obligation was universal, it was impractical to train and equip every able-bodied man, so after 1572 the practice was to select a proportion of men for the Trained Bands, who were mustered for regular training.[5][13][14][15][16][17][18]

When war broke out with Spain training and equipping the militia became a priority, and in 1588 veteran officers were sent to supervise preparations in the maritime counties of Dorset, Hampshire, Sussex and Kent.[1][12][19] The arrival of the Spanish Armada led to the mobilisation of the trained bands on 23 July, Dorset sending its cavalry and a large number of infantry to London. It was reported that one of the Dorset contingents had offered £500 for the honour of serving as the royal bodyguard. Queen Elizabeth gave her Tilbury speech on 9 August to the army camped at Tilbury on the Thames Estuary. The rest of the Dorset men went to their stations when the fire beacons were lighted and they shadowed the Spanish fleet as it sailed up the English Channel. After the defeat of the Armada, the army was dispersed to its counties, but the men were to hold themselves in readiness. There were several more alarms over the following years, notably in 1596, and the Trained Bands were regularly mustered and exercised, but were never called to active service.[1][20][21]

With the passing of the threat of invasion, the trained bands declined in the early 17th Century. Later, King Charles I attempted to reform them into a national force or 'Perfect Militia' answering to the king rather than local control.[1][22][23][24] Dorset was ordered to send a contingent to Newcastle upon Tyne for the Second Bishops' War of 1640. However, substitution was rife and many of those sent on this unpopular service would have been untrained replacements. When they reached Faringdon in Berkshire they broke into mutiny and murdered one of their officers. When this was suppressed and the march was resumed, almost half the men had deserted.[25]

Control of the militia was one of the major points of dispute between Charles I and Parliament that led to the First English Civil War. Once hostilities began, neither side made much further use of the Trained Bands except as a source of recruits and weapons for their own full-time regiments.[1][26][27][28][29] Early in the conflict in September 1642 Dorset Trained Bandsmen were called out by both sides for the Siege of Sherborne Castle, Col Hugh Rogers' regiment serving in the Royalist garrison, while Sir Thomas Trenchard's regiment and the Dorchester Trained Band were in the Parliamentarian blockading force. The Parliamentarians did not press the siege, but after they withdrew the Royalist army dispersed to Cornwall and South Wales, and those members of the Dorset TBs who had not joined one of the fulltime regiments presumably dispersed to their homes. In 1643 the Dorchester TB was present when that town was captured by the Royalists virtually without a fight.[30][31][32][33]

Once Parliament had re-established full control it passed new Militia Acts in 1648 and 1650 that replaced lords lieutenant with county commissioners appointed by Parliament or the Council of State. At the same time the term 'Trained Band' began to disappear in most counties. Under the Commonwealth and Protectorate the militia received pay when called out, and operated alongside the New Model Army to control the country.[34][35]

Restoration Militia

After the Restoration of the Monarchy, the English Militia was re-established by the Militia Act 1661 under the control of the king's lords-lieutenant, the men to be selected by ballot. This was popularly seen as the 'Constitutional Force' to counterbalance a 'Standing Army' tainted by association with the New Model Army that had supported Cromwell's military dictatorship, and almost the whole burden of home defence and internal security was entrusted to the militia under politically reliable local landowners.[1][36][37][38][39][40] The militia were frequently called out during the reign of King Charles II; their duties included suppressing non-conformist religious assemblies (of which there were many in the West Country) under the Conventicle Act 1664.[41]

Two of Dorset's deputy lieutenants, Robert Coker of Mappowder (a former Parliamentary officer and captain of Militia Horse) and George Fulford, were commended by the Privy Council for promptly mustering the Dorset Militia when a French invasion of the Isle of Purbeck was feared during the Popish Plot crisis in 1678.[42][43]

Monmouth's rebellion

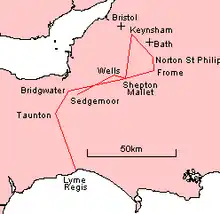

In 1685 the Duke of Monmouth launched his rebellion by landing at Lyme Regis in Dorset on 11 June. He chose to begin his campaign in the West Country because of the level of support he expected in that strongly Protestant region, where economic recession was hurting the weavers and clothiers. As his rebels mustered the government of James II responded by declaring him a traitor and calling out the militia on 13 June while the regulars of the Royal army were assembled.[44][45][46]

At this time the Lord Lieutenant of Dorset was John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol and the officers of the Dorset Militia included:[47]

- Colonel Thomas Strangways, MP and DL for Dorset, and commanding the whole Dorset Militia in the absence of the Earl of Bristol[48][49]

- Col Thomas Erle, MP for Wareham and DL for Dorset, who was a Major in the Royal Army[50][51]

- Captain of Horse Richard Fowns, MP for Corfe Castle and DL for Dorset[52]

- Captain of Foot Thomas Chafin, MP for Poole and DL for Dorset[53]

The Dorset Militia at this time comprised five regiments of Foot and one of Horse, which mustered at the following towns:[54]

- Blandford (The East Dorset Militia, commanded by Col Erle)

- Bridport (The Red Regiment commanded by Col Strangways)

- Dorchester

- Shaftesbury

- Sherborne

- Dorchester (Horse)

The Dorset Militia reacted quickly to the invasion: a party of the Militia Horse and the constable's watch were patrolling the road between Lyme and Bridport by 12 June when they skirmished with a group of mounted officers from Monmouth's army. Although the rebels charged the militia, killing two and driving them back, the militia and watchmen were backed by larger numbers, and the rebels withdrew.[55] By 14 June the Red Regiment had assembled at Bridport under Col Strangways. On that day Monmouth sent a force against them under Lord Grey of Werke with Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Venner commanding about 40 horsemen and Maj Nathaniel Wade some 450 foot. Scouting ahead, a vanguard of about 40 of the most experienced musketeers advanced in thick mist and surprised the militia outguard of about 12 men that Strangways had posted at the West Bridge. The outguard fell back onto the mainguard (about 36 musketeers and pikemen) at the crossroads, which exchanged a volley with the advancing rebels. The rebel vanguard being supported by a further 100 musketeers the militia party fell back along the High Street towards their main body in camp at the East Bridge, alerting the officers and volunteers billeted in the Bull Inn. In the High Street, the rebels skirmished with the Militia Horse, who were trying to secure their mounts and broke into the Bull Inn. In the confusion, two militia officers, Edward Coker (DL for Dorset and son of Robert Coker of Mappowder) and Wadham Strangways (DL for Dorset and brother of Col Strangways), were killed at the Bull Inn, though not before Coker shot and wounded Venner. Meanwhile, Col Strangways had been joined by Maj Erle and the deployed the rest of the Red Regiment at the East Bridge. This was barricaded, with a 'killing ground' in front where the narrow High Street opened out to the bridge approach. The fire of the militia behind their barricade and probably in the adjoining houses drove back the rebels, killing 7 and capturing 23. Grey and the rebel horse fled back to Lyme, but Wade extracted the foot in good order. Strangways did not follow up.[56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64]

The day after the skirmish at Bridport, the East Dorset Regiment marched into the town from Blandford, and the Dorset Militia from the Sherborne area hovered around Yeovil and the line of the River Parrett on Monmouth's flank. On 17 June John, Lord Churchill, arrived at Bridport with the cavalry of the Royal army. Next day the Dorset Militia marched out with Churchill in pursuit of Monmouth. After Bridport Monmouth had advanced from Lyme to Axminster, just in time to prevent a junction of the Devon and Somerset Militia. Some of the Somersets fled, many joining Monmouth, and Monmouth followed up into that county; the Devons fell back and blocked his way westwards, as the Dorsets had blocked the way into East Dorset. While the Dorsets with Churchill closely followed Monmouth, the Devons re-occupied Lyme and Taunton behind him. Finding the Gloucestershire and Wiltshire Militia also blocking the routes into those counties, Monmouth was unable to reach Bristol and fell back into Somerset, where Churchill joined the Royal forces under the Earl of Feversham.[10][56][58][60][65][66][67][68]

At the Battle of Norton St Philip on 27 June, Feversham posted the Dorset Militia, together with those of Somerset and Oxfordshire in the line while the Regulars attempted to attack the village. Although the rebels repulsed this attack, they did not dare to attack Feversham's position, and continued their retreat to Frome and then to Bridgwater. The speed of the march was such that the Dorset Militia were exhausted, and Feversham (who did not trust the militia) sent them home to Dorset to keep the peace there and maintain the cordon drawn round the rebels.[58][60][68][69][70][71] On the night of 5/6 July Monmouth launched a desperate attack on Feversham's camp (the Battle of Sedgemoor), but his scratch forces were destroyed by the regulars.[10][58][72][73][74][75] Major Thomas Erle and Capt Thomas Chaffin of the Dorset Militia fought as volunteers under Churchill at Sedgemoor.[51][53]

Four days after Sedgemoor King James ordered the militia to be stood down across the country, but those of the West Country still had work to do in hunting down rebels and pacifying the countryside. James II deliberately belittled their performance to play down Monmouth's skill and to bolster his own plans for a large army under his own control. After the suppression of the rebellion he suspended militia musters and planned to use the counties' weapons and militia taxes to equip and pay his expanding Regular Army, which he felt he could rely upon, unlike the locally commanded militia.[36][76][77][78]

The West Country militia was not mustered for training in 1687, and was not embodied when William of Orange made his landing in the West Country in 1688 (the Glorious Revolution). It is impossible to say whether the Dorset Militia would have supported James or William, but the officers who were MPs all supported William, and Robert Coker, a former Parliamentary and Militia officer, and recently removed as a DL for Dorset, was instrumental in bringing over the Dorset Militia for William.[42][79][lower-alpha 3]

The militia was restored to its former position under William III. When all the counties mustered their militia in 1697, Dorset had two Troops of Horse with 8 officers and 118 men, and 23 Companies of Foot with 69 officers and 1760 men, organised into two regiments.[81] But the Militia passed into virtual abeyance during the long peace after the Treaty of Utrecht in 1712.[82]

1757 Reforms

Under threat of French invasion during the Seven Years' War a series of Militia Acts from 1757 reorganised the county militia regiments, the men being conscripted by means of parish ballots (paid substitutes were permitted) to serve for three years. In peacetime they assembled for 28 days' annual training. There was a property qualification for officers, who were commissioned by the lord lieutenant. An adjutant and drill sergeants were to be provided to each regiment from the Regular Army, and arms and accoutrements would be supplied when the county had secured 60 per cent of its quota of recruits.[36][56][83][84][85]

Dorsetshire was given a quota of 640 men in one regiment, and George Pitt, MP, later Lord Rivers, was commissioned as colonel on 25 October 1757. Not only was he the first militia colonel to be commissioned under the Act, but his regiment was the first to be completed, receiving its arms on 27 August 1758.[56][86][87][lower-alpha 4] The Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Lieutenant of Dorset, reviewed part of the new regiment near Cranbourne in October that year and expressed himself satisfied with their appearance. The regiment was embodied at Dorchester for actual service on 21 June 1759 (again, together with the Wiltshire Militia on the same day, the first regiment to be embodied).[12][56][86][87]

On first embodiment, the regiment was quartered at Exeter. From July to October 1760 it was in camp near Winchester, and then went into winter quarters near Blandford Forum, where it also returned in the winters of 1761–62 and 1762–63, with some companies at Dorchester.[56] In the summer of 1762 the regiment (together with the 21st Foot and the Cornwall Militia) formed part of Lt-Gen Edward Carr's Brigade camped in Chatham Lines, protecting the dockyard.[91] The war ended with the signature of the Treaty of Paris in February 1763, and the militia could be stood down: the Dorset Militia was disembodied in April 1763.[12][56][86]

The militia was kept in being over the next 15 years, with vacancies among the officers filled by the lord lieutenant, and the men occasionally mustered, for example in July 1767 when Lord Shaftesbury reviewed the regiment at Dorchester.[92]

American War of Independence

The American War of Independence broke out in 1775, and by 1778 Britain was threatened with invasion by the Americans' allies, France and Spain, while the bulk of the Regular Army was serving overseas. The militia were called out and the Dorset regiment assembled at Blandford on 20 April 1778 under Lt-Col Michel.[12][86][92]

Over the following years the regiment spent the summer months at one of the training camps, where the militia were exercised alongside regular troops while providing a reserve in case of French invasion. The regiment spent four months in 1778 in camp at Winchester; in 1779 and 1782 it was at Coxheath Camp near Maidstone in Kent, which was the army's largest training camp; in 1780 and 1780 it was camped on Southsea Common. Winters were spent in quarters in Dorset. Invasion fears were at their height in 1779 when French troops were massed along the Channel coast and a Franco-Spanish fleet appeared at the mouth of the Channel (the 'Armada of 1779'), but maladministration led to a disastrous epidemic in the combined fleet and the militia guarding the coast were not called into action. With the Treaty of Paris in 1783 the militia was disembodied.[12][86][92][93]

From 1784 to 1792 the militia ballot was used to keep up the numbers of the disembodied militia, but to save money only two-thirds of the men were actually mustered for annual training.[94]

French Revolutionary War

The militia was already being embodied when Revolutionary France declared war on Britain on 1 February 1793. The Dorset Militia had been called out as early as 17 December 1792. After assembling at Blandford, with an establishment of 672 rank and file in 10 companies, it marched to Portsmouth in February 1793.[12][86][95]

The French Revolutionary Wars saw a new phase for the English militia: they were embodied for a whole generation, and became regiments of full-time professional soldiers (though restricted to service in the British Isles), which the regular army increasingly saw as a prime source of recruits. They served in coast defences, manning garrisons, guarding prisoners of war, and for internal security, while their traditional local defence duties were taken over by the Volunteers and mounted Yeomanry.[36][96][97] The Dorset Militia were moved around the counties south of the River Thames and east of Dorset, usually on the invasion-threatened coast in the summer months.[95] In August 1793 the regiment was part of a large militia encampment at Ashdown Forest,[98] in 1796 it was guarding French prisoners of war at Porchester Castle and in 1797 it garrisoned Hurst Castle. Winter quarters were twice in the Thames Valley, at Wallingford and Henley, once in West Surrey, and once in the Winchelsea–Hastings area of East Sussex.[95]

Supplementary Militia

.jpg.webp)

In 1794 the regiment's establishment was increased to 840, the additional recruits being volunteers raised 'by beat of drum' rather than the ballot. In an attempt to have as many men as possible under arms for home defence in order to release regulars, in 1796 the Government created the Supplementary Militia, a compulsory levy of men to be trained for 20 days a year in their spare time, and to be incorporated in the Regular Militia in emergency. Rural Dorset's quota was only increased by 185 men. The regiment's establishment was increased to 1000 and no additional units were required.[87][95][99][100][101]

The regiment's home base was at Fordington, Dorset, where the parish Overseers of the Poor were responsible for the wives and families of numerous militiamen, especially after the increase in establishment.[102]

In July 1798 George Damer, 2nd Earl of Dorchester, succeeded George Pitt, Lord Rivers, as colonel of the regiment, the Hon George Pitt was promoted from Major to 2nd Lt-Col, Capt William Morton Pitt, MP, became 2nd Major, and Captain-Lieutenant Edward Digby, 2nd Earl Digby was promoted to captain. (The Earl of Dorchester had first been commissioned into the Dorset Militia as a lieutenant in 1778 but had left the following year to join the newly raised 87th Foot as major, until it was disbanded in 1783.)[95][103] Three months later, George Pitt became 1st Lt-Col, Maj Richard Bingham was promoted to 2nd Lt-Col and William Morton Pitt became senior major; Capt Earl Digby resigned.[104]

Ireland 1798–9

A Rebellion broke out in Ireland in 1798 and in August a French force was landed to support the rebels. The English Militia were invited to volunteer for service in Ireland and the Dorset (600 men) and Devon regiments embarked aboard the frigate HMS Arethusa on 31 August.[12][88][95][8][102][105] They were still in transit when a decisive battle took place at Ballinamuck in County Longford and the French surrendered; the militia were landed again. However, the invitation was renewed shortly afterwards and nearly every man of the regiment volunteered. They landed at Waterford on 11 September and were stationed at Carrick-on-Suir from 2 to 29 September. Among their duties the militia had to search Carrick for arms, but they only appear to have located rusty old guns and swords. They were despatched to Fermoy and Kerrick, north of Cork, but were back in Carrick by October 22 and remained there for the next year.[106]

Although the rebellion had been suppressed, Ireland was still disturbed. On one occasion the regiment confronted a large body of rebels, who dispersed before they could be engaged, on another the regiment killed two notorious rebels hiding out in a wood. Intelligence having been received that there was going to be trouble at Coolnamuck, near Carrick where number of prisoners were being held, a Mr Jephson preceded there with a force of Yeomanry Cavalry assisted by the Dorset Militia. There they took into custody seven persons on 6 September 1799. That night about 300 people assembled and during the ensuing disturbances another nine were taken into custody. Thereafter things generally quietened down and the government decided that there was no longer a need for such large numbers of troops in Ireland. The English Militia, including the Devon and Dorset contingents, returned to England in late 1799. Before the Dorset Militia left the mayor and corporation of Carrick presented the Earl of Dorchester with a sword and the officers with mess plate.[12][88][95][102]

Since 1798 officers and men of the militia had been encouraged to volunteer to transfer to the Regular Army, and many Dorset men accepted the bounty. As a consequence, the regiment's establishment was reduced to 770 in July 1799, and by November it had only 377 men. The establishment was down to 411 by 1802.[87][95][107] Between 1798 and 1814 48 officers, with their quotas of non-commissioned officers and men, transferred from the Dorset Militia into the regiments of the line, Royal Artillery, Royal Marines etc.[88]

From Ireland the regiment had sailed to land at Pill, Somerset, on 12 October 1799 and then marched back to Dorset. The Fordington Overseers accounts show that a number of men returned there from Ireland and were discharged.[95][102] In December 1799 the Earl of Dorchester and Lt-Col George Pitt both resigned, and Lt-Col Richard Bingham and Maj W.M. Pitt were promoted to succeed them.[95][108][109][110][111]

The regiment then returned to duty in South West England, in garrisons and guarding prisoners of war. The militia was stood down after the Treaty of Amiens and the Dorset Militia was disembodied at Dorchester on 24 April 1802.[86][95]

Napoleonic War

However, the Peace of Amiens quickly broke down and the militia were recalled, the Dorsets being embodied again at Dorchester on 28 March 1803, still under Col Bingham.[12][86][112] The establishment strength was 496 men, soon increased to 730 when the Supplementary Militia were called up. Before the end of the year the regiment was moved to Sussex, which was the most likely place for a French invasion. An alarm on 1 January 1804 saw the regiment deployed for five days at Shoreham-by-Sea ready to repel a landing. Most of 1804 was spent camped at Beachy Head. Not until after the defeat of the French fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 was the regiment permitted to return to Dorset. Thereafter it mainly did duty in Dorset, Devon and Hampshire; it was in Cornwall in 1811, and in East Anglia in 1812.[112]

In 1813 the regiment volunteered for service in Ireland once more, spending mid-1813 to September 1814 stationed at Limerick. It was commanded by Col Bingham, assisted by Lt-Col Richard T. Steward and Maj Nathaniel T. Still.[12][88][112][113] By later 1814 the war had ended, and the regiment returned to Dorchester to be disembodied in February 1815. It was not called upon during the short Waterloo campaign later that year.[12][88][86][112]

Long peace

After Waterloo there was another long peace. Although officers continued to be commissioned into the militia and ballots were still held until 1831, the regiments were rarely assembled for training: the Dorsets only trained in May 1820, May 1821, May 1825 and September 1831,[88][114] but they were recalled briefly in 1830 to contain the spread of the Swing Riots, which never really affected Dorset. The permanent staff of sergeants and drummers at Dorchester were progressively reduced.[115]

When Col Bingham died in 1824, Earl Digby, by now Lord Lieutenant of Dorset, appointed himself colonel of the regiment.[116] He resigned in 1846 and Sir John James Smith, 3rd Baronet, was appointed to succeed him.[88][112][111][117][118]

1852 Reforms

The Militia of the United Kingdom was revived by the Militia Act 1852, enacted during a renewed period of international tension after Napoleon III was declared Emperor of the French. As before, units were raised and administered on a county basis, and filled by voluntary enlistment (although conscription by means of the Militia Ballot might be used if the counties failed to meet their quotas). Training was for 56 days on enlistment, then for 21–28 days per year, during which the men received full army pay. Under the Act, militia units could be embodied by Royal Proclamation for full-time home defence service in three circumstances:[119][120]

- 'Whenever a state of war exists between Her Majesty and any foreign power'.

- 'In all cases of invasion or upon imminent danger thereof'.

- 'In all cases of rebellion or insurrection'.

The Dorset Militia was revived in 1852, with younger officers appointed, including a number of former Regular officers. Colonel Richard Hippisley Bingham, formerly a captain in the Madras Army, succeeded the elderly Sir John James Smith on 26 July 1852. The county's militia quota was set at 506 men, augmented in 1853 with a further 308.[114][121][122]

Crimean War and after

War having broken out with Russia in 1854 and an expeditionary force sent to the Crimea, the militia began to be called out for home defence. The Dorset Militia was embodied on 7 December 1854.[12][86] It was stationed at Dorchester until early in 1856 when it moved to Gosport.[123][124][125] A peace treaty having been signed in March 1856, the regiment was disembodied in June 1856.[86]

From 1852 to 1873 the Dorset Militia usually carried out its annual training at Dorchester. The regiment constructed a barracks in the town during the 1860s to house the permanent staff and armoury.[114][126]

The Militia Reserve introduced in 1867 consisted of present and former militiamen who undertook to serve overseas in case of war.[119][114]

Cardwell Reforms

Under the 'Localisation of the Forces' scheme introduced by the Cardwell Reforms of 1872, militia regiments were brigaded with their local regular and Volunteer battalions. Sub-District No 39 (County of Dorset) was formed in Southern District with headquarters at Weymouth and the following units assigned:[86][122]

- 39th (Dorsetshire) Regiment of Foot

- 75th (Stirlingshire) Regiment of Foot

- Dorset Militia at Dorchester

- 1st Administrative Battalion, Dorsetshire Rifle Volunteers, at Dorchester

The militia now came under the War Office rather than their county lords lieutenant. Around a third of the recruits and many young officers went on to join the regular army.[119][114][127] The sub-districts were to establish a brigade depot for their linked battalions, and the militia barracks at Dorchester were chosen as the site. A new complex, 'The Keep', incorporating the old barracks (the 'Little Keep'), was built in 1879 and the Brigade Depot moved from its temporary site at Weymouth.[122][126] The original intention had been to have two militia battalions in each regimental district, but Dorset was a thinly-populated rural county and the proposed 2nd Dorset Militia was never formed.[122][128]

Following the Cardwell Reforms a mobilisation scheme began to appear in the Army List from December 1875. This assigned places in an order of battle to Militia units serving Regular units in an 'Active Army' and a 'Garrison Army'. The Dorset Militia's assigned war station was with the Garrison Army in the Portland defences.[122]

Training for the militia now became more intensive: in 1874 the Dorset Militia carried out its annual training at Aldershot and then took part in that year's manoeuvres. Afterwards training was in Dorset, at Poole, Lulworth or Weymouth.

Dorset Regiment

.jpg.webp)

The Childers Reforms took Cardwell's reforms further, with the linked battalions forming single regiments. From 1 July 1881 a new Dorset Regiment was formed with the 39th Foot as the 1st Battalion, the 54th (West Norfolk) Regiment of Foot (rather than the 75th Foot) became the 2nd Battalion, and the Dorset Militia became the 3rd Battalion.[86][12][89][122][128]

Second Boer War

At the start of the Second Boer War 1899, most of the regular battalions were sent to South Africa, the Militia Reserve was mobilised to reinforce them and many militia units were called out to replace them for home defence. The 3rd Dorsets were embodied from 14 December 1899 to 13 July 1901, but unlike some militia units did not see any overseas service, although considerable numbers of its militia reservists did so.[12][86][129]

Special Reserve

After the Boer War, there were moves to reform the Auxiliary Forces (militia, yeomanry and volunteers) to take their place in the six army corps proposed by St John Brodrick as Secretary of State for War. However, little of Brodrick's scheme was carried out.[130][131] Under the sweeping Haldane Reforms of 1908, the militia was replaced by the Special Reserve (SR), a semi-professional force similar to the previous militia reserve, whose role was to provide reinforcement drafts for regular units serving overseas in wartime.[132][133][134] The 3rd (Dorset Militia) Bn now became the 3rd (Reserve) Bn (SR). Only 180 other ranks transferred from the militia to the new battalion, against an establishment of 1009 all ranks, but it had grown to about 400 by the outbreak of World War I.[86][122][129]

World War I

On the outbreak of war the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion was embodied at Dorchester on 4 August 1914 under the command of Lt-Col E.C. Castleman Smith, CB, and went to its war station at Weymouth. Here it served in the Portland Garrison and trained reinforcement drafts for the regular Dorset battalions serving overseas (the 1st Bn on the Western Front, the 2nd Bn in Mesopotamia). When the 2nd Bn was besieged at Kut al Amara from December 1915 the relieving force included a large draft from the 3rd Bn destined for the 2nd. This was combined with a similar draft for the 2nd Bn Norfolk Regiment to form a 'Composite English Battalion' in 21st Indian Brigade of 7th (Meerut) Division. This battalion was nicknamed the 'Norsets' and fought in the desperate attempts to break through to Kut. After the fall of Kut the Norsets continued in service until further reinforcements arrived and the Dorset elements formed the 2nd (Provisional) Bn of the regiment, eventually replacing the Regular 2nd Bn.[86][122][135][136][137]

The 7th (Reserve) Battalion of the Dorsets was formed fn November 1914 from the surplus volunteers training with the 3rd Bn at Weymouth, initially as a service battalion of Kitchener's Fourth New Army ('K4') in 102nd Brigade of 34th Division. On 10 April 1915 the division was broken up and in May the 7th became a second reserve battalion at Wool to provide reinforcements for the K1 and K2 battalions of the Dorsets.[86][135][136][138]

In June 1915 the 3rd Bn moved a short way from Weymouth to Wyke Regis where it remained for the rest of the war. When Lt-Col Castleman-Smith retired in 1916, he was replaced by Maj Worship from the Royal Munster Fusiliers who had been invalided home from Gallipoli. On 1 June 1916 the 3rd Bn formed the 1st (Home Service) Bn of the Dorsets, which also served in the Portland garrison until it was disbanded in January 1917. Apart from a short posting to Wareham from July to October 1915, the 7th Bn remained at Wool with 8th Reserve Brigade, where the 2nd (Home Service) Garrison Battalion (designated 8th (Home Service) Bn from 1 November 1916) of the Dorsets was formed on 1 September 1916 and completed by SR drafts. This battalion also served at Portland before joining 219th Brigade of 73rd Division at Blackpool in November. It moved to Danbury, Essex, in January 1917 and was disbanded on 14 December 1917, the men being distributed among 219th Bde. The 7th Bn was redesignated the 35th Bn of the Training Reserve in 8th Reserve Bde on 1 September 1916 and later transferred to the Devonshire Regiment.[86][135][136][139]

Instead of being demobilised at the end of the war the 3rd Bn was sent in March 1919 to Ireland under active service conditions. It was stationed at Derry where it absorbed the 3/4th Bn (the reserve for the Territorial Force battalions). The 1st Bn arrived at Derry in May and the remaining personnel of 3rd Bn were transferred to it on 28 July 1919. The 3rd Bn was then disembodied on 21 August.[86][140]

Postwar

The SR resumed its old title of Militia in 1921 but like most militia units the 3rd Dorsets remained in abeyance after World War I. By the outbreak of World War II in 1939, no officers remained listed for the 3rd Bn. The Militia was formally disbanded in April 1953.[86][122]

Heritage and ceremonial

Precedence

In 1759 it was ordered that militia regiments on service were to take precedence from the date of their arrival in camp. In 1760 this was altered to a system of drawing lots where regiments did duty together. During the War of American Independence the counties were given an order of precedence determined by ballot each year. For the Dorset Militia the positions were:[90][92]

- 30th on 1 June 1778

- 44th on12 May 1779

- 6th on 6 May 1780

- 14th on 28 April 1781

- 42nd on 7 May 1782

The militia order of precedence balloted for in 1793 (Dorset was 43rd) remained in force throughout the French Revolutionary War: this covered all the regiments in the county. Another ballot for precedence took place in 1803 at the start of the Napoleonic War and remained in force until 1833: Dorset was 50th. In 1833 the King drew the lots for individual regiments and the resulting list continued in force with minor amendments until the end of the militia. The regiments raised before the peace of 1763 took the first 47 places: the Dorsets became 42nd. Most regiments took little notice of the numeral. Indeed, the Dorsets kept the number '1' on their buttons from their claim to be the first militia regiment revived in 1758.[89][90][95][88][114][115][122]

Uniforms and insignia

The regiment's uniforms from the 1758 review at Cranbourne onwards were red with green facings. As 3rd Dorsets after 1881 the facings changed to the standard white of English county regiments. The 39th Foot had previously worn grass green facings, and these were re-adopted by the whole of the Dorset Regiment in 1904.[56][89][122][114]

Until 1881 the Dorset Militia wore the crest of Lord Rivers (who as the Hon George Pitt had re-raised the regiment in 1758) on its appointments, and in 1914 the SR officers still wore this as a collar badge.[89][114]

About 1810 an officer's gilt shoulder-belt plate had the Royal cypher 'GR' above the numeral '1' within a crowned garter inscribed 'DORSET MILITIA', with a laurel wreath either side. Officers' coatee and tunic buttons of 1830–81 carried the numeral '1' with a crown above and the word 'DORSET' below. The officers' waistbelt plate of 1855–81 had the crowned royal cypher 'VR' within a circle inscribed with the title.[89]

Examples of the Dorset Militia cap badge are not common and where they do exist they appear to be of a standard Victorian Shako Plate with a crown an facetted eight-pointed star, with a central motif of an ornate numeral one surrounded by a belted title bearing the title "Dorset Militia", or in the case of the Glengarry the standard Dorset Regiment badge with the Gibraltar castle and motto Primus In Indis (First in India) and a circlet with "Dorsetshire" inscribed.[141]

Honorary Colonels

The following served as Honorary Colonel of the regiment:[12][112][122]

- Col Richard Hippisley Bingham, former CO, appointed 1873

- Edward Digby, 10th Baron Digby, appointed 25 April 1891

- Col H.C.G. Batten, appointed 2 March 1906

Portraits

Members of the local Dorset gentry joined the militia and a number were painted in their uniforms, notably:[142]

- Colonel David Robert Michel painted by Thomas Gainsborough circa 1760

- Lieutenant Sir Gerard Napier painted by Joshua Reynolds circa 1762[143]

- Colonel George Pitt, First Lord Rivers painted by Thomas Gainsborough circa 1768;[144] and then by Thomas Beach circa 1780 and Thomas Gooch circa 1782

Regimental museum

The Dorset Regiment Museum and that of its militia units was located at The Keep Museum in Dorchester.

Memorials

There is a memorial brass plate in St. Mary's Church, Bridport, to Edward Coker, killed at the Bull Inn during the Dorset Militia's skirmish with Monmouth's rebels on 1 June 1685.[64]

See also

Footnotes

- It is incorrect to describe the British Militia as 'irregular': throughout their history they were equipped and trained exactly like the line regiments of the regular army, and once embodied in time of war they were fulltime professional soldiers for the duration of their enlistment.

- 'Dorset' and 'Dorsetshire' are use interchangeably in most older sources and documents; 'Dorset' is preferred today.

- Major Thomas Erle of the Dorset Militia went on to raise a regiment of foot for William during the Glorious Revolution and fought with it at the Battle of the Boyne. He then took command of Luttrell's Regiment (later the Green Howards), served as a Brigadier-General at the Battle of Landen and as a Lieutenant-General at the Battle of Almansa and Siege of Lille. He was promoted to full General in 1711 and retired as commander-in-chief in England.[50][51][80]

- In later years it wore the number '1' on its buttons to commemorate this, irrespective of the precedence it had been assigned.[88][89][90]

Notes

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 3–6.

- Fortescue, Vol I, p. 12.

- Fissel, pp. 178–80.

- Hay, pp. 60–2, 64–5.

- Holmes, pp. 90–1.

- Kerr, p. 1.

- Scott, pp. 55–8.

- Michael Russell, 'Background to the Militia and the Irish Rebellion of 1798', Dorset Online Parish Clerks.

- Fissel, p. 181.

- Kerr, pp. 105–7.

- Nicholson, Appendix VI.

- Hay, p. 353.

- Cruickshank, pp. 17, 24–5.

- Fissel, pp. 178–87.

- Fortescue, Vol I, pp. 12, 16, 125.

- Hay, pp. 11–17, 88.

- Scott, p. 61.

- "The Militia – The Keep Military Museum, Dorchester, Dorset". www.keepmilitarymuseum.org. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Hay, p. 91.

- Boynton, pp. 180–1.

- Hay, p. 89.

- Fissel, pp. 174–8, 190–5.

- Hay, pp. 97–8.

- Dorset Trained Bands at BCW Project.

- Fissel, pp. 208, 262–3.

- Burne & Young, pp. 6–7.

- Cruickshank, p. 326.

- Rogers, pp. 17–8.

- Reid, pp. 1–2.

- Rogers' Regiment at BCW Project.

- Trenchard's Regiment at BCW Project.

- Dorchester TB at BCW Project.

- Reid, pp. 40–1, 59.

- Hay, pp. 98–104.

- Western, p. 8.

- Holmes, pp. 94–101.

- Fortescue, Vol I, pp. 294–5.

- Macaulay, Vol I, p. 143.

- Scott, pp. 68–73.

- Western, pp. 3–29.

- Western, pp. 33–5.

- Coker at History of Parliament Online.

- Fulford at History of Parliament Online.

- Chandler, pp. 7–8, 19, 22.

- Macaulay, Vol I, pp. 279–80, 283.

- Scott, Table 2.1.2, p. 55.

- Scott, Tables 2.2.2, p. 71; 2.2.3, p. 74; 2.2.4, p. 76.

- Scott, p. 374.

- Strangways at History of Parliament Online.

- Scott, p. 365.

- Erle at History of Parliament Online.

- Fowns at History of Parliament Online.

- Chaffin at History of Parliament Online.

- Scott, Table 3.1.2, p. 94; 3.2.2, p. 127.

- Scott, p. 265.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 7–9.

- Chandler, p. 20.

- Chandler, pp. 124–30.

- Macaulay, Vol I, pp. 282–3.

- Scott, Table 2.1.2, p. 55; Table 4.3.2, p. 167.

- Scott, pp. 167–8 and fn 61; pp. 177–8, 266–72 and fn 58.

- Watson, p. 217.

- Seccombe, Thomas (1899). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58. p. 418.

- IWM War Memorials Register, ref 26610.

- Kerr, pp. 5–6.

- Macaulay, pp. 289–92.

- Scott, pp. 170, 252–62, 272, 291–2.

- Western, pp. 54–7.

- Chandler, pp. 32–7.

- Macaulay, pp. 292–94.

- Scott, pp. 264, 278–9, 286.

- Chandler, pp. 38–71.

- Macaulay, pp. 295–9.

- Scott, pp. 289–90.

- Watson, pp. 242-50.

- Chandler, pp. 73–5, 186–7.

- Fortescue, Vol I, pp. 302–3.

- Scott, pp. 77–82; 332–5.

- Scott, pp. 82–3.

- Frederick, p. 106.

- Camden Miscellany, 1953, Vol 20, p. 8.

- Fortescue, Vol II, p. 133.

- Fortescue, Vol II, pp. 288, 299–302.

- Hay, pp. 136–44.

- Western, pp. 124–57, 251.

- Frederick, pp. 88–9.

- Western, Appendices A & B.

- Sleigh, p. 83.

- Parkyn.

- Baldry.

- Cormack.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 9–10.

- Herbert.

- Fortescue, Vol III, pp. 530–1.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 10–11.

- Clammer.

- Knight, pp. 78–9, 111, 255, 411.

- Sargeaunt, p. 85.

- Fortescue, Vol V, pp. 167–8, 198–204.

- Hay, pp. 148–52.

- Western, pp. 220–3.

- Michael Russell, 'Fordington Overseers' Accounts, 1798–1802', Dorset Online Parish Clerks.

- London Gazette, 3 July 1798.

- London Gazette, 30 October 1798.

- The Times, 1 September 1798.

- Diary of James Ryan, a land surveyor in Carrick in 1798, preserved in Waterford County Museum, quoted at Dorset Online Parish Clerks.

- Western, pp. 227–36.

- London Gazette, 17 December 1799.

- War Office, 1805 List.

- "The New Monthly Magazine". E. W. Allen. 1824. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Haigh, Lesley. "Elizabeth Kellaway and her Bingham Descendents". www.leshaigh.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 11–2.

- "The Gentleman and Citizen's Almanack ... for the Year of Our Lord ..." S. Powell. 1814. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 12–4.

- Hay, pp. 154–5.

- London Gazette, 8 June 1824.

- London Gazette, 20 January 1846.

- Hart's.

- Dunlop, pp. 42–5.

- Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 91–2.

- London Gazette, 30 July 1852.

- Army List, various dates.

- Edinburgh Gazette, 9 February 1855.

- Edinburgh Gazette, 8 January 1856.

- Edinburgh Gazette, 12 February 1856.

- 'History of our Building' at The Keep.

- Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 195–6.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 1–3.

- Atkinson, pp. 111–2.

- Dunlop, pp. 131–40, 158-62.

- Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 243–54.

- Dunlop, pp. 270–2.

- Frederick, pp. vi–vii.

- Spiers, Army & Society, pp. 275–7.

- Atkinson, Pt III, pp. 119, 128–30.

- James, p. 81.

- Perry, pp. 86–8.

- Becke, Pt 3b, p. 137.

- Becke, Pt 2b, pp.111–6.

- Atkinson, Pt III, p. 141.

- "Victorian Dorsetshire Militia Glengarry Badge of white metal with two loops to the reverse, top l". www.the-saleroom.com. 5 May 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Military – British Army – Fencibles & Militia | Ireland | British Museum". Scribd. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Portrait Of Sir Gerard Napier by Joshua Reynolds". Pixels. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Portrait of George Pitt, First Lord Rivers | Cleveland Museum of Art". www.clevelandart.org. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

References

- C.T. Atkinson, The Dorsetshire Regiment: The Thirty-Ninth and Fifty-Fourth Foot and the Dorset Militia and Volunteers, Oxford: Privately printed at the University Press (for the regiment?), 1947.

- W.Y. Baldry, 'Order of Precedence of Militia Regiments', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 15, No 57 (Spring 1936), pp. 5–16.

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2b: The 2nd-Line Territorial Force Divisions (57th–69th), with the Home-Service Divisions (71st–73rd) and 74th and 75th Divisions, London: HM Stationery Office, 1937/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-39-8.

- Maj A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3b: New Army Divisions (30–41) and 63rd (R.N.) Division, London: HM Stationery Office, 1939/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-41-X.

- Lindsay Boynton, The Elizabethan Militia 1558–1638, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1967.

- David G. Chandler, Sedgemoor 1685: An Account and an Anthology, London: Anthony Mott, 1685, ISBN 0-907746-43-8.

- David Clammer, 'Dorset's Volunteer Infantry 1794–1805', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 89, No 357 (Spring 2011), pp. 6–25.

- Andrew Cormack, 'An Officer of the Cornwall Militia, 1760', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 76, No 307 (Autumn 1998), pp. 151–6.

- C.G. Cruickshank, Elizabeth's Army, 2nd Edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Mark Charles Fissel, The Bishops' Wars: Charles I's campaigns against Scotland 1638–1640, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-521-34520-0.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol I, 2nd Edn, London: Macmillan, 1910.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol II, London: Macmillan, 1899.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol III, 2nd Edn, London: Macmillan, 1911.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol V, 1803–1807, London: Macmillan, 1910.

- J.B.M. Frederick, Lineage Book of British Land Forces 1660–1978, Vol I, Wakefield: Microform Academic, 1984, ISBN 1-85117-007-3.

- Lt-Col H.G. Hart, The New Annual Army List, and Militia List (various dates from 1840).

- Col George Jackson Hay, An Epitomized History of the Militia (The Constitutional Force), London:United Service Gazette, 1905.

- Brig Charles Herbert, 'Coxheath Camp, 1778–1779', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 45, No 183 (Autumn 1967), pp. 129–48.

- Richard Holmes, Soldiers: Army Lives and Loyalties from Redcoats to Dusty Warriors, London: HarperPress, 2011, ISBN 978-0-00-722570-5.

- Brig E.A. James, British Regiments 1914–18, London: Samson Books, 1978, ISBN 0-906304-03-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1-84342-197-9.

- W.J.W. Kerr, Records of the 1st Somerset Militia (3rd Bn. Somerset L.I.), Aldershot:Gale & Polden, 1930.

- Lord Macaulay, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, Popular Edn, London:Longman, 1895.

- Ranald Nicholson, 'Edward III and the Scots, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965.

- H.G. Parkyn, 'English Militia Regiments 1757–1935: Their Badges and Buttons', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 15, No 60 (Winter 1936), pp. 216–248.

- F.W. Perry, History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 5b: Indian Army Divisions, Newport, Gwent: Ray Westlake, 1993, ISBN 1-871167-23-X.

- Stuart Reid, All the King's Armies: A Military History of the English Civil War 1642–1651, Staplehurst: Spelmount, 1998, ISBN 1-86227-028-7.

- Capt B.E. Sargeaunt, The Royal Monmouthshire Militia, London: RUSI, 1910/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, nd, ISBN 978-1-78331204-7.

- Christopher L. Scott, The military effectiveness of the West Country Militia at the time of the Monmouth Rebellion, Cranfield University PhD thesis 2011.

- Arthur Sleigh, The Royal Militia and Yeomanry Cavalry Army List, April 1850, London: British Army Despatch Press, 1850/Uckfield: Naval and Military Press, 1991, ISBN 978-1-84342-410-9.

- War Office, A List of the Officers of the Militia, the Gentlemen & Yeomanry Cavalry, and Volunteer Infantry of the United Kingdom, 11th Edn, London: War Office, 14 October 1805/Uckfield: Naval and Military Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1-84574-207-2.

- J.N.P. Watson, Captain-General and Rebel Chief: The Life of James, Duke of Monmouth, London: Allen & Unwin, 1979, ISBN 0-04-920058-5.