8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot

The 8th (King's) Regiment of Foot, also referred to in short as the 8th Foot and the King's, was an infantry regiment of the British Army, formed in 1685 and retitled the King's (Liverpool Regiment) on 1 July 1881.

| 8th (King's) Regiment of Foot | |

|---|---|

_Regiment_of_Foot_Badge.jpeg.webp) Cap badge of the 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot | |

| Active | 19 June 1685 – 1 July 1881 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Army |

| Type | Line Infantry |

| Size | Two battalions |

| Regimental Depot | Peninsula Barracks, Warrington |

| Nickname(s) | The Leather Hats, The King's Hanoverian White Horse |

| Motto(s) | Nec Aspera Terrent (Difficulties be Damned) |

| Colours | Blue |

| March | Here's to the Girl |

| Anniversaries | Blenheim (13 August) Delhi (14 September) |

| Battle honours | Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Dettingen, Martinique 1809, Niagara, Delhi 1857, Lucknow, Peiwar Kotal |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel of the Regiment | General Thomas Gerrard Ball (1861–1881) |

As infantry of the line, the 8th (King's) peacetime responsibilities included service overseas in garrisons ranging from British North America, the Ionian Islands, India, and the British West Indies. The duration of these deployments varied considerably, sometimes exceeding a decade; its first tour of North America began in 1768 and ended in 1785.

The regiment served in numerous conflicts during its existence, notably in the wars with France that dominated the 18th and 19th centuries, the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Indian rebellion of 1857 (historically referred to as the "Indian Mutiny" by Britain). As a consequence of Childers reforms, the 8th became the King's (Liverpool Regiment). A pre-existing affiliation with the city had derived from its depot being situated in Liverpool from 1873 because of the earlier Cardwell reforms.

History

The regiment formed as the Princess Anne of Denmark's Regiment of Foot during a rebellion in 1685 by the Duke of Monmouth against King James II.[1] After James was deposed during the "Glorious Revolution" that installed William III and Mary II as co-monarchs, the regiment's commanding officer, the Duke of Berwick, decided to join his royal father in exile.[2] His replacement as commanding officer was Colonel John Beaumont, who had earlier been dismissed with six officers for refusing to accept a draft of Catholics.[2]

It took part in the Siege of Carrickfergus in Ireland in 1689[3] and in the Battle of the Boyne the following year.[4] Further actions, while under the command of John Churchill (later 1st Duke of Marlborough) took place that year involving the regiment during the sieges of Limerick, Cork and Kinsale.[4]

War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714)

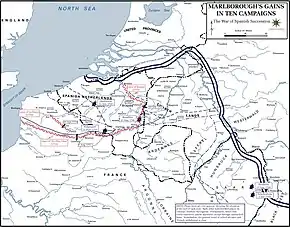

For almost a decade, the regiment undertook garrison duties in England, Ireland, and the Dutch United Provinces, where it paraded for King William on Breda Heath in September 1701.[5] On the accession of Princess Anne to the throne in 1702, the regiment became the Queen's Regiment of Foot, although it continued to be referred to as Webb's Regiment per an unofficial army convention that had a unit known by the name of its colonel.[6] The War of the Spanish Succession, predicated on a dispute between a "Grand Alliance" and France over who would succeed Charles II of Spain, reached the Low Countries in April 1702. While Dutch marshal Prince Walrad took the initiative and besieged Kaiserswerth, the French Marshal duc de Boufflers forced Walrad's colleague, the Earl of Athlone, to withdraw deep into the Dutch Republic.[7] Supporting Athlone's army, the Queen's Regiment fought near Nijmegen in a rearguard action during the Dutch Army's retreat between the Maas and Rhine rivers.[6] John Churchill, Earl (later Duke) of Marlborough, ranked as Captain-General with limited authority over Dutch forces, arrived in the Low Countries soon afterwards to assume control of a multi-national army organised by the Grand Alliance. He invaded the French-controlled Spanish Netherlands and presided over a series of sieges at Venlo, Roermond, Stevensweert, and Liège, in which the regiment's grenadier company breached the citadel. After a lull during the winter, Marlborough struggled to retain the cohesion of his army against the inclination of Dutch generals to divide his resources, while the army itself experienced a reverse at Liège in 1703.[8]

Later in the year, the regiment assisted in the capture of Huy and Limbourg,[8] but the campaigns in 1702 and 1703 nevertheless "were largely indecisive".[9] To aid the beleaguered Austrian Habsburgs and preserve the alliance, Marlborough sought to engage the French in a definitive set-piece battle in 1704 by advancing into Bavaria, an ally of France, and combining his force with that of Prince Eugene.[9] As an army of 40,000 men assembled, Marlborough's elaborate programme of deception concealed his intentions from the French.[9][10] The army invaded Bavaria on 2 July and promptly captured the Schellenberg after a devastating assault that included a contingent from the Queen's.[11] On 13 August, the Allies encountered a Franco-Bavarian army under the overall command of the duc de Tallard, beginning the Battle of Blenheim. The Queen's Regiment, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Sutton, supported General Lord Cutts' left wing, opposite to French-held Blenheim.[11] According to a contemporary account by Francis Hare, Chaplain-General of Marlborough's army, the Queen's secured a French-constructed "barrier" to prevent it being used as a route of escape, taking hundreds prisoner in its vicinity.[12] Blenheim had become congested with French soldiers and its streets filled with dead and wounded.[11] About 13,000 French soldiers eventually surrendered, including Tallard, while the collective carnage caused more than 30,000 soldiers to become casualties.[13]

The effective collapse of Bavaria as a French ally and the capture of its most significant fortresses followed Blenheim by year's end.[13] After a period of recuperation and reinforcement in Nijmegen and Breda, the Queen's returned to active service during the Allies' attempted invasion of France, via the Moselle, in May 1705.[14] In June, French Marshal Villeroi captured Huy and besieged Liège, forcing Marlborough to abort a campaign that lacked appreciable Allied support.[15] The regiment became detached from Marlborough's army to assist in the retaking of Huy before rejoining for the subsequent attack on the Lines of Brabant[14] Although the lines were overcome, French resistance, combined with opposition among some Dutch generals and adverse weather conditions, prevented much exploitation.[15] The Queen's helped to seize Neerwinden, Neerhespen, and the bridge at Elixheim.[16]

In May 1706, Villeroi, pressured by King Louis XIV to atone for France's earlier defeats, initiated an offensive in the Low Countries by crossing the Dyle river.[17] Marlborough engaged Villeroi's army near Ramillies on 23 May.[17] Along with 11 battalions and 39 squadrons of cavalry under Lord Orkney,[17] the Queen's fought initially in what transpired to be a feint attack on the left flank of the French lines.[16] The feint convinced Villeroi to divert troops from the centre,[17] while Marlborough had to use representatives to repeatedly instruct Orkney not to continue the attack.[16] Most of Orkney's battalions, including the Queen's, redeployed to support Marlborough on the left. By 19:00, the Franco-Bavarian army had completely disintegrated. For the remainder of 1706, the Allies systematically captured towns and fortresses, including Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, and Ghent.[17] The regiment fought its last siege of 1706 at Menin, one of the most formidably defended fortresses in Europe.[18]

The threat of a French-supported Jacobite uprising in Scotland arose in 1708 and the Queen's was among those regiments recalled to Britain.[16] Once the Royal Navy intercepted an invasion fleet off the English coast, the regiment returned to the Low Countries, disembarking at Ostend.[19] The French later returned to the offensive, attacking Flanders and capturing territory that had been lost in 1706.[16] Marlborough had positioned his forces near Brussels, anticipating that an offensive might be directed against the city,[16] and had to march his army 50 miles (80 km) over a period of two days.[20] On 11 July, Marlborough led an Allied army against Bourgogne, grandson of King Louis, and Marshal Vendôme's 100,000–man army at the Battle of Oudenarde. The Queen's joined an advanced contingent under Lord Cadogan which crossed the Scheldt, via pontoon bridges assembled near Oudenarde, as a prelude to the arrival of the main army.[16] While elements of the main army began to arrive at the bridges, Cadogan advanced on the village of Eyne and swiftly overwhelmed an isolated group of four Swiss mercenary battalions; three surrendered and the fourth attempted to withdraw but was intercepted by Jørgen Rantzau's cavalry.[21] To signify the surrender, the commanding officer of the Queen's received some of their colours. The regiment soon became engaged in battle near the village of Herlegem, fighting through the hedges until darkness.[22] Cadogan's precarious situation only began to alleviate by the deployment of the Duke of Argyll's reinforcements.[23]

The Queen's became occupied by a succession of sieges: at Ghent, Bruges, and Lillie.[24] In 1709, the regiment assisted in the protracted Siege of Tournai, which capitulated in September. On the 11th, the regiment fought in the bloodiest battle of the war: Malplaquet. After being committed from reserve in the battle's closing stages, the regiment advanced under heavy fire and fought through dense wood, having Lieutenant-Colonel Louis de Ramsay killed.[24] The memoirs of Private Matthew Bishop, of the Queen's Regiment, contained an account that recalled: "the French were well prepared to give us a warm salute. It soon broke us in a terrible manner, though our vacancies were quickly filled up...when we got clear of the dead and wounded, we ran upon them and returning their fire, even broke them out of the breast-work."[25]

In 1710, the regiment was represented at the sieges of Douai, Béthune, Aire and St. Venant.[26]

Jacobites and renewed European conflict (1715–1768)

Rebellion against the Hanoverian King George I began in 1715 by Jacobite supporters of James Stuart, "Old Pretender" to the throne of Great Britain. As unrest escalated in Britain, the Queen's Regiment arrived in Scotland and became absorbed by a Government army under the Duke of Argyll.[27] Although numerically superior, the Jacobite army did not begin an advance south until November because of the caution of their leader, the Earl of Mar.[28][29] The Duke of Argyll moved north from Stirling and positioned his forces in the vicinity of Dunblane on 12 November.[28] On the morning of the 13th, in conditions that had frozen the ground during the night, the Battle of Sheriffmuir began.[28]

The Queen's Regiment formed part of General Thomas Whetham's left wing. Confused troop movements led to both it and the Jacobite left being weaker than the corresponding right wing.[30] While Whetham's men attempted to readjust their dispositions, a mass of Highlanders began a rapid charge.[27] Entwined in hand-to-hand combat within minutes, the sides fought until Whetham's men broke and retreated in disarray.[30] The Queen's had 111 killed, including Lieutenant-Colonel Hanmer, 14 wounded, and 12 captured.[27] The remnants withdrew from the battlefield until almost upon Stirling.[27] Without cavalry support, the Jacobite left also broke,[28] and the Earl of Mar abandoned the area at nightfall.[27]

In 1716 at the behest of George I, to honour the regiment's service at Sheriffmuir, the Queen's became the King's Regiment of Foot, with the White Horse of Hanover (symbol of the Royal Household) as its badge.[31]

The King's remained in Scotland until 1717, by which time the Jacobite uprising had been suppressed.[32] The regiment served in Ireland between May 1717 and May 1721[33] and between winter 1722 and spring 1727.[34] The regiment embarked to Flanders in winter 1742 for service in the War of the Austrian Succession.[35] It fought at the Battle of Dettingen in June 1743 where, despite the French enjoying superiority in numbers, Britain and its Allies defeated an army under the duc de Noailles.[36] The regiment also took part in the Battle of Fontenoy in May 1745: the King's Regiment was positioned in the frontline of the Duke of Cumberland's army but a retreat was eventually ordered.[37]

In 1745, Prince Charles Edward (popularly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie) landed in Scotland, seeking to restore the Stuarts to the British throne. The regiment did not become committed to battle until the Battle of Falkirk in January 1746.[38] The regiment was part of the left wing of the front line of the army, under the command of Lieutenant-General Henry Hawley. After a failed attack by dragoons of Hawley's army, the Highlanders loyal to Prince Charles charged the Government forces, compelling the left wing of the army to withdraw while the right wing held. The rebels and Government armies both withdrew from the battlefield by night-time.[39] The regiment also fought in the Battle of Culloden in April 1746.[39] Once the impetuous Highlanders charged and overcame the initial volley of fire, vicious hand-to-hand fighting ensued with Hawley's men. The King's provided cross-fire support, firing across the front-line and into the Highlanders. The regiment sustained a single, severely wounded casualty.[39]

The King's fought in the Battle of Rocoux in October 1746[40] and the Battle of Lauffeld in July 1747. In the latter, the King's and three other regiments became embroiled in a protracted struggle through the avenues of Val. Control of the village fluctuated throughout the battle until the Allies retreated before overwhelming numbers.[41]

The British Army implemented a numbering system in 1751 to reflect the seniority of a regiment by its date of creation, with the King's becoming the 8th (King's) Regiment of Foot in the order of precedence.[31] The beginning of the Seven Years' War, which would encompass Europe and its colonial possessions, necessitated the 8th's expansion to two battalions, amounting to a total of 20 companies.[42] Both battalions formed part of an expedition in 1757 that captured Île d'Aix, an island off the western coast of France,[42] as a precursor to a planned seizure of the mainland garrison town of Rochefort.[43] The 2nd Battalion became the 63rd Regiment of Foot in 1758.[44]

When the regiment augmented the Hanoverian Army in 1760, the 8th King's had its grenadier company committed to the battles of Warburg and Kloster Kampen. As a complete regiment, the 8th served at Kirch-Denkern, Paderborn, Wilhelmsthal, and the capture of Cassel.[42]

American Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

The 8th Foot arrived in Canada in 1768 and had its ten companies dispersed to garrison isolated posts on the Great Lakes: Fort Niagara (four), Fort Detroit (three), Fort Michilimackinac (two), and Fort Oswego (one).[45] As the regiment's deployment appeared to near completion, protests in the eastern colonies began to intensify, evolving from vocal concerns about self-determination and taxation without representation, to rebellion against Britain in 1775.[46]

During its posting, the 8th Foot possessed a number of officers adept in cultivating a relationship with tribes on the Great Lakes,[47] notable amongst them being Captain Arent DePeyster and Lieutenant John Caldwell. Later to become 5th Baronet of County Fermanagh's Caldwell Castle, Caldwell immersed himself in his efforts to foster understanding between the British and Ojibwa, reputedly marrying a member of the tribe and becoming a chief under the adopted name of "The Runner".[48] In the west, Captain DePeyster's negotiations proved instrumental in maintaining peace between the British and tribes such as the Mohawk and Ojibwa nations. Born into a prominent New York City family of Dutch origin, DePeyster held authority over Fort Michilimackinac. In 1778, using £19,000 of goods as leverage, he arranged for more than 550 warriors from several tribes to serve in Montreal and Ottawa.[49]

The invasion of Canada by American generals Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold began in mid-1775. By the end of November, the Americans had captured Fort St. Jean, Montreal, and Fort Chambly, and besieged the city of Quebec.[50] An attempt to storm it in December resulted in Montgomery's death. Reinforcements from Europe raised the siege in May 1776 and expelled the almost starved and exhausted Americans from the area.[51] After the lifting of the siege, a small party from the 8th Foot led the regiment to its first significant battle in the war.[52]

From Fort Oswegatchie, Captain George Forster, of the regiment's light company, led a composite force, including 40 regulars and about 200 warriors, across the St. Lawrence River to attack Fort Cedars, held by 400 Americans under Timothy Bedel.[53] Forster maintained illicit contact with occupied Montreal,[53] and received intelligence of American troop movements using Indian operatives and Major de Lorimier.[54] On arriving at the fort on 18 May, the British briefly exchanged fire before Forster parleyed with Bedel's successor, Major Isaac Butterfield, to request his surrender and warn him of the consequences should Indian warriors be committed to battle.[55] Butterfield, whose men had apparently been disconcerted by an earlier display of Indian war chanting, expressed a willingness to do so on the proviso of being allowed to retire with his weapons – a condition that Forster refused.[53]

Butterfield conceded the fort on the 19th, on the day an American relief force of about 150 resumed its advance on the Cedars, having previously reembarked aboard bateaux because of exaggerated scout reports.[53] Once he learned of the column's presence, Forster had a detachment ambush the Americans from positions astride the only available path through the forest.[56] The relief's commander, Major Sherburne, surrendered, but the engagement infuriated the Indian contingent as the Allies' only fatality was a Seneca war chief.[53] Forster managed to dissuade them from executing the prisoners by paying substantial ransoms for some of the captives as compensation for the loss.[57]

Emboldened by the two victories, the British landed at Pointe-Claire, on the Island of Montreal, only to withdraw after Forster established the strength of General Benedict Arnold's force at Lachine.[53] In pursuit of a dwindling column, Arnold followed the British using bateaux, but was deterred from landing by Forster's placement of men along the embankment at Quinze-Chênes, supported by two captured cannon pieces.[58] On the 27th, Forster sent Sherburne under a flag of truce to inform Arnold that terms to a prisoner exchange favourable to the British had been agreed upon. Arnold accepted the conditions, with the exception of Americans being forbidden from serving elsewhere. Both Arnold and Forster had postured during the battle, each threatening the other with the prospect of atrocities: the killing of prisoners by Forster's Indian allies and the destruction of Indian villages by Arnold's men.[53] The exchange would be denounced by the American Second Continental Congress and the arrangement reneged upon under the pretext that abuses had been committed by Forster's men.[53]

In late July 1777, the regiment contributed Captain Richard Leroult and 100 men to the Siege of Fort Stanwix. Commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Barry St. Leger, 34th Foot,[59] the force ambushed the American troops at the Battle of Oriskany in August 1777: however a few weeks later the siege collapsed with the disappearance of the dis-spirited native allies.[60]

The regiment took part in further actions at Vincennes and the Battle of Newtown (Elmira, New York) in 1779, as well as the Mohawk Valley in 1780 and Kentucky in 1782.[61] Captain Henry Bird of the 8th Regiment led a British and Native American siege of Fort Laurens in 1779. In 1780, he led an invasion of Kentucky,[61] capturing two "stations" (fortified settlements) and returning to Detroit with 300 prisoners.[62] The regiment returned to England in September 1785.[63]

French Revolutionary War

In 1793, revolutionary France declared war on Great Britain. The King's became assigned to an expeditionary force sent to the Netherlands under the command of Prince Frederick, Duke of York.[63] In 1794, the regiment attempted to lift the French Siege of Nijmegen. The allies planned a nocturnal attack, with the march conducted without audible commotion. The force leapt into the French earthworks, with hand-to-hand fighting ensuing. Despite the success, the town of Nijmegen was soon evacuated and the British withdrew from the Netherlands in 1795.[64]

In 1799, the King's became resident on Menorca, which had been captured from Spain the previous year.[65] In 1801, the regiment landed at Abukir Bay, Egypt, with an expedition sent under the command of General Ralph Abercromby to counter a French invasion.[66] The King's participated in the capture of Rosetta, 65 miles west of Alexandria,[67] and a fort located in Romani.[68] The British completed the occupation of Egypt by September.[68]

Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812

The regiment was sent to Gibraltar in 1802 and returned to England in 1803.[69] It landed at Cuxhaven in Germany in October 1805 as part of the Hanover Expedition, but was withdrawn in February 1806[70] before taking part in the Battle of Copenhagen in August 1807.[71]

The 1st Battalion moved to Canada in 1808 as the Napoleonic Wars extended to the Americas.[71] Within a year, in January 1809, the battalion had embarked at Barbados with an expeditionary force comprising two divisions assembled to invade Martinique.[71] Although a number of engagements with the French garrison preceded the island's seizure, disease represented the principal threat to Britain's five-year occupation. By October 1809, some 1,700 of more than 2,000 casualties had succumbed to disease.[72] The 8th Foot returned to Nova Scotia in April, having had its commanding officer, Major Bryce Maxwell, and four others killed in a skirmish with French soldiers on the Surirey Heights during the advance on Fort Desaix in February.[73] When sustained tension between the United States and Britain culminated in the War of 1812, the 1st and 2nd battalions were based in Quebec and Nova Scotia respectively.[74]

Sporadic raids into Canada on the eastern frontier provided impetus for a former regimental officer, Lieutenant-Colonel "Red" George MacDonnell, to encroach into New York State and attack Ogdensburg in February 1813.[75] To reach their destination, the 8th Foot and Canadian militia had to traverse across the frozen St. Lawrence River and through dense snow.[76] After gaining control of the fort following close-quarters battle, the British destroyed the main barracks and three anchored vessels,[76] and departed with provisions and prisoners. Ogdensburg would not be reestablished as a frontier garrison, ensuring relative peace in the region.[77]

In April 1813, two companies of the 8th, elements of the Canadian militia, and Native American allies attempted to repulse an American attack on York (present-day Toronto).[78] As the Americans landed on the shoreline, the grenadier company engaged them in a bayonet charge with 46 killed, including its commanding officer, Captain Neal McNeale. The Americans nevertheless overwhelmed the area but subsequently incurred 250 casualties, notably General Zebulon Pike, when retreating British regulars detonated Fort York's Grand Magazine.[79]

While garrisoning Fort George, at Newark (present day Niagara-on-the-Lake), in May 1813 with companies of the Glengarries and Runchey's Company of Coloured Men, the 8th Foot attempted to disrupt an amphibious landing by the Americans. Although numerically inferior, the British delayed the invasion and retreated without disorder.[80] In June 1813, the 8th and 49th regiments assaulted an American encampment at Stoney Creek. Five companies from the two British regiments engaged more than 4,000 Americans in a nocturnal battle. Although the Americans had two brigadiers captured and suffered losses, the British commander, Colonel John Harvey, considered the possibility of his opponents realising their numerical advantage too compelling to ignore and withdrew.[81]

In July 1814 the regiment fought in the Battle of Chippawa in which the British commander General Phineas Riall retreated after he misidentified American regulars for militia.[82] Later in the month, the regiment fought in the Battle of Lundy's Lane.[83] The British, Canadian and Native soldiers, under the command of Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond, engaged the American force. It was one of the bloodiest battles recorded on Canadian territory.[84] The following month, the King's took part in the action at Snake Hill during the siege of Fort Erie.[85] In September 1814 the Americans attacked the British posts with overwhelming force and the regiment suffered heavy losses.[85] The King's Regiment received the battle honour 'Niagara' for its contributions to the war.[86] The regiment landed back in England in summer 1815.[86]

Indian rebellion and Second Afghan War

Between the end of the war and the Indian rebellion of 1857, the King's undertook a variety of duties in Bermuda, Canada, Cephalonia, Corfu, Gibraltar, Ireland, Jamaica, Malta and Zante. In 1846, the regiment began a 14-year posting to India, stationed initially in the Bombay Presidency. At the beginning of the rebellion in May 1857, the 8th Foot occupied a cantonment in Jullundur, together with three Indian regiments and two troops of horse artillery.[87]

The complex array of motives and causes that culminated in the mutiny of much of the Bengal Army would be catalysed in 1857 by rumours that beef and pork fat was being used to grease paper rifle cartridges. Confined first to a number of Bengal regiments, the mutiny eventually manifested in some areas as a more diverse, albeit disparate, rebellion against British rule.[88][89] Soon after reports were received of the first mutiny at Meerut on 10 May, the 8th's commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Hartley, had two companies secure the fort of Phillaur, near Jullundur, due to the significance of its magazine stores and reports that the 3rd Bengal Native Infantry intended to seize it.[89]

After a period of seven weeks in Jullundur, the regiment became attached to an army preparing to besiege Delhi. Because of a shortage of troops, due primarily to cholera and other diseases, several weeks elapsed before the British had attained a strength sufficient to commence operations.[89]

In July 1857, two companies supported a position that had been under attack for seven hours. The King's participated in the capture of Ludlow Castle, in the vicinity of Kashmir Gate in the northern walls of Delhi. Grouped into the 2nd Column with the 2nd Bengal Fusiliers and 4th Sikhs, the 8th King's attacked Delhi early on 14 September with the intent of capturing the Water Bastion and Kashmiri Gate.[90] Once the city had been secured by the British, the 8th's Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Greathed vacated his position and became commander of a column dispatched to Cawnpore. The regiment, commanded by Major Hinde, had been seriously depleted and the combined total of it and the 75th Foot numbered just 450.[91] The regiment also took part in the second Relief of Lucknow in November, seeing much action until withdrawing, after the evacuation of civilians, on the 22nd. In an environment of systematic reprisal by the British, Captain Octavius Anson, of the 9th Lancers, recalled observing acts of punitive violence against Indian civilians, including the alleged killing of incapacitated villagers by soldiers of the 8th Foot.[92]

The 1st Battalion was brought back to Britain in 1860.[93] It spent the year 1865 in Dublin, Ireland, where the battalion supported garrison operations against Irish Republican activity in the city.[94] Then, after two years in Malta, the 1st King's returned to India in 1868.[94] where it remained for a decade.[95] The regiment's 2nd Battalion, which had been reconstituted in 1857,[96] was itself posted to Malta (in 1863) and India (in 1877), and met up with the 1st King's on the island and at Mundra, in the Bombay Presidency.[95]

Within a year of the battalion's arrival in India,[95] in November 1878, Britain invaded Afghanistan when an ultimatum to its ruler by the Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton, went unanswered.[97] Lytton's demands had followed the reluctant hosting of a Russian mission to Kabul by Sher Ali and the prevention of a similar British mission from entering Afghanistan at Ali Masjid.[98] Though still acclimatising and consequently susceptible to fever, the 2nd King's was allocated to the Kurram Valley Field Force, under Major-General Frederick Roberts.[99] The 2nd King's fought at the Battle of Peiwar Kotal in November 1878.[100]

The regiment was not fundamentally affected by the Cardwell Reforms of the 1870s, which gave it a depot at Peninsula Barracks, Warrington from 1873, or by the Childers reforms of 1881 – as it already possessed two battalions, there was no need for it to amalgamate with another regiment.[101] Under the reforms the regiment was renamed the King's Regiment (Liverpool) on 1 July 1881.[31]

Colonels

Colonels of the Regiment were:[31]

Princess Anne of Denmark's Regiment of Foot

- 1685–1687: Col Robert Shirley, Lord Ferrers of Chartley

- 1687–1688: Lt-Gen James FitzJames, 1st Duke of Berwick

- 1688–1695: Col John Beaumont

- 1695–1715: Lt-Gen John Richmond Webb

Queen's Regiment of Foot

- 1715–1720: Brig-Gen Henry Morrison

King's Regiment of Foot

- 1720–1721: Sir Charles Hotham, 4th Baronet

- 1721–1732: Brig-Gen. John Pocock

- 1732–1738: Col. Charles Lenoe

- 1738–1745: Lt-Gen. Richard Onslow

- 1745–1759: Lt-Gen. Edward Wolfe

8th (The King's) Regiment

- 1759–1764: Major-Gen. The Hon. John Barrington

- 1764–1766: Lt-Gen. John Stanwix

- 1766–1772: Lt-Gen. Daniel Webb

- 1772–1794: Gen. Bigoe Armstrong

- 1794–1814: Gen. Ralph Dundas

- 1814–1825: Gen. Edmund Stevens

- 1825–1846: Gen. Henry Bayly, GCH

- 1846–1854: Gen. Sir Gordon Drummond, GCB

- 1854–1855: Lt-Gen. John Duffy, CB, KC

- 1855–1860: Gen. Roderick Macneil

- 1860–1861: Maj-Gen. Eaton Monins

- 1861–1881: Gen. Thomas Gerrard Ball

For colonels after 1881 see King's Regiment (Liverpool)

Notes

- Mileham (2000), p. 1

- Mileham (2000), pp. 2-3

- Cannon (1844), p. 17

- Cannon (1844), p. 18

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. xxii

- Mileham (2004), p. 4

- The Spanish Succession: 1702 - King William III dies Archived 21 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, spanishsuccession.nl. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- Mileham (2000), p. 5

- Hoppit (2002), p. 116

- Chandler, David (2003), p83

- Mileham (2000), p. 6

- Murray (1845), p. 407

- Black (1998), p. 50

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 23

- Sundstrom (1991), p. 151

- Mileham (2000), p. 7–8

- Chandler (2003), p70–3

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 26

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 27

- Jones (2001), p. 280

- Churchill (1947), pp. 363-4

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 29

- Churchill (1947), p. 368-9

- Mileham (2000), p. 9

- Nicolas, Nicholas Harris & Southern, Henry (1828), The Retrospective Review, and Historical and Antiquarian Magazine, p52

- Cannon (1844), p. 45

- Mileham (2000), p. 11-2

- Szechi (2006), pp. 151-2

- Black (1996), p. 100

- Roberts (2002), p. 45

- Mills, T.F. "The King's Regiment (Liverpool)". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2004. Retrieved 8 November 2005.

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 39

- Cannon (1844), p. 51

- Cannon (1844), p. 52

- Cannon (1844), p. 53

- Cannon (1844), p. 54

- Cannon (1844), p. 55

- Cannon (1844), p. 56

- Cannon (1844), p. 57

- Cannon (1844), p. 58

- Cannon (1844), p. 60

- Mileham (2000), p. 15

- Szabo (2007), p. 80

- "63rd (West Suffolk) Regiment of Foot". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- Houlding (1981), p. 17

- Cannon (1844), p. 66

- Mileham (2000), p. 19

- Mileham (2000), p. 21

- Nester (2004), p. 198

- Barnes & Royster (2000), pp. 72-3

- Allen (1992), p. 47

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), pp. 56-7

- Morrissey & Hook (2003), pp. 66-8

- Stanley (1977), p. 119

- Nester (2004), p. 106

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), pp. 57-8

- Kingsford (1893), p. 51

- Stanley (1977), p. 122

- Cannon (1844), p. 70

- Cannon (1844), p. 71

- Potter, William L. "Redcoats on the Frontier: The King's Regiment in the Revolutionary War". National Park Service. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- Banta (1998), p. 158

- Cannon (1844), p. 72

- Cannon (1844), p. 73

- Cannon (1844), p. 74

- Cannon (1844), p. 76

- Cannon (1844), p. 77

- Cannon (1844), p. 78

- Cannon (1844), p. 79

- Cannon (1844), p. 80

- Cannon (1844), p. 81

- Buckley (1998), p. 265

- Mileham (2000), p. 36.

- Cannon (1844), p. 84

- Whitfield, Carol M. (2000). "MacDonnell (McDonald), George Richard John". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- Mileham (2000), p. 37.

- Turner (2000), p. 68.

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), pp. 76–77.

- Benn (1993), pp. 54–56

- Cannon (1844), p. 88

- Cannon (1844), p. 91

- Cannon (1844), p. 95

- Cannon (1844), p. 96

- Heidler (2004), p. 161

- Cannon (1844), p. 99

- Cannon (1844), p. 100

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), pp. 103

- Parsons (1999), pp. 45-6

- Mileham (2000), p. 49

- Raugh (2004), p. 119

- Roberts (1897), pp. 141-2

- Collier (1964), p. 270

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), p. 151-2

- Cannon, Cannon & Cunningham (1883), pp. 155-6

- Mileham (2000), pp. 56-7

- Mileham (2000), p. 53

- Riddick (2006), p. 72

- Hopkirk (1992), pp. 382-3

- Roberts (1897), p. 349

- "Battle of Peiwar Kotal". British Battles. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "Training Depots 1873–1881". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2016. The depot was the 13th Brigade Depot from 1873 to 1881, and the 8th Regimental District depot thereafter

References

- Allen, Robert (1992). His Majesty's Indian Allies: British Indian Policy in the Defence of Canada. Dundurn.

- Banta, Richard (1998). The Ohio. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813109596.

- Barnes, Ian; Royster, Charles (2000). The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415922432.

- Benn, Carl (1993). Historic Fort York, 1793-1993. Natural Heritage. ISBN 978-0-92047-479-2.

- Black, Jeremy (1998). Britain as a Military Power, 1688-1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857287721.

- Black, Jeremy (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Modern Warfare. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521470339.

- Buckley, Roger Norman (1998). The British Army in the West Indies. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813016047.

- Cannon, Richard (1844). Historical Record of the Eighth, or the King's Regiment of Foot. London: Parker, Furnivall and Parker.

- Cannon, Richard; Cannon, Robertson; Cunningham, Alexander (1883). Historical Record of the King's Liverpool Regiment of Foot. Harrison and sons. ISBN 978-1-4368-7227-0.

- Chandler, David (2003). The Oxford History of the British Army. Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 0-19-280311-5.

- Collier, Richard (1964). The Great Indian Mutiny: A Dramatic Account of the Sepoy Rebellion. Dutton.

- Churchill, Winston (1947). Marlborough: His Life and Times. George G. Harrap & Co.

- Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T. (September 2004). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-362-8.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1992). The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4770017031.

- Hoppit, Julian (2002). A Land of Liberty? England 1699-1727. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199251001.

- Houlding, J.A. (1981). Fit for Service: The Training of the British Army, 1715-1795. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198226475.

- Jones, Archer (2001). The Art of War in the Western World. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252069666.

- Kingsford, William (1893). The History of Canada. Vol. 6. General Books.

- Mileham, Patrick (2000). Difficulties Be Damned: The King's Regiment - A History of the City Regiment of Manchester and Liverpool. Fleur de Lys. ISBN 1-873907-10-9.

- Morrissey, Brendan; Hook, Adam (2003). Quebec 1775: The American Invasion of Canada. Osprey. ISBN 978-1841766812.

- Murray, Sir George (1845). The letters and dispatches of John Churchill, 1702 to 1712. John Murray.

- Nester, William (2004). The Frontier War for American Independence. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0811700771.

- Parsons, Timothy (1999). The British Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A World History Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0847688241.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576079256.

- Riddick, John F. (2006). The History of British India: A Chronology. Praeger. ISBN 978-0313322808.

- Roberts, Frederick Sleigh (1897). Forty-one Years in India: From Subaltern to Commander-in-Chief. Richard Bently and Son.

- Roberts, John (2002). The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745. Polygon. ISBN 978-1902930299.

- Stanley, George Francis Gillman (1977). Canada Invaded, 1775-1776. Samuel Stevens Hakkert. ISBN 978-0888665782.

- Sundstrom, Roy (1991). Sidney Godolphin: Servant of the State. EDS Publications. ISBN 978-0874134384.

- Szabo, Franz (2007). The Seven Years' War in Europe: 1757-1763. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582292727.

- Szechi, Daniel (2006). 1715: The Great Jacobite Rebellion. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300111002.

- Turner, Wesley (2000). The War of 1812: The War That Both Sides Won. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1550023367.