Abílio de Nequete

Abílio de Nequete (Fih-el-Khoura, Lebanon, February 15, 1888 - Porto Alegre, August 7, 1960) was a Lebanese-Brazilian barber, teacher and political activist. Born into a family of Orthodox Christians, he immigrated to Brazil at the age of 14, in 1903, settling in the city of São Feliciano (now Dom Feliciano), a district of Encruzilhada do Sul. There he became a peddler, working together with his father, with whom he had a conflicting relationship, even politically, since his father was a federalist and Abílio joined the Republican Party.

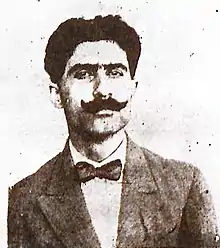

Abílio de Nequete | |

|---|---|

Abdo Nakat | |

Abílio de Nequete in 1919 | |

| Born | February 15, 1888 Fih-el-Khoura, Lebanon |

| Died | August 7, 1960 Porto Alegre, Brazil |

| Nationality | Lebanese-Brazilian |

| Occupation(s) | Barber, teacher and political activist |

| Political party | Communist Party of Brazil (until 1923) |

| Movement | Socialism, communism (until 1923), technocracy (1923 on) |

| Parent |

|

He moved to Porto Alegre between 1907 and 1908, where he worked as a barber. In the Gaucho capital he converted to Spiritism and joined the labor movement. He stood out as one of the main leaders of the great general strikes of 1917 and 1919, besides having founded, in 1918, the Maximalist Union of Porto Alegre (União Maximalista de Porto Alegre), a group that would later be part of the foundation of the Communist Party of Brazil (Partido Comunista Brasileiro - PCB) in 1922, party of which Nequete was General Secretary until 1923.

Away from the PCB, Abílio de Nequete reconnected with republicanism and began to show an interest in technocracy, interpreting it through his own political theory and creating a corresponding religion, Evidentism. He became a professor at the Escola de Comércio and died in August 1960, victim of an illness.

First years

Abílio de Nequete was born on February 15, 1888, in the village of Fih-el-Khoura, in northern Lebanon, under the name Abdo Nakat, into an Orthodox Christian family. His mother died some time after his birth, and at the age of two his father, Miguel Nakat, immigrated to Brazil. Nequete was left with an older sister, who would also immigrate a few years later. At the age of 14, in 1903, with no news of his father, he decided to travel in order to find him, boarding a cargo ship headed for Brazil.[1]

Arriving in the city of Rio Grande, Nequete contacted the local Arab community and, with the information he obtained, headed to São Feliciano (now Dom Feliciano), a district of Encruzilhada do Sul. There, Abílio de Nequete became a peddler, working together with his father. Abílio had a conflictive relationship with his father, even politically, since Miguel was a federalist and Abílio joined the Republican Party. Between 1907 and 1908, Abilio moved to Porto Alegre, where he started working as a barber. In the Gaucho capital, Nequete went to live on Conde de Porto Alegre Street, located in the Fourth District: the city's industrial core where factory workers lived.[1] In Porto Alegre, he converted to Spiritualism and began to serve in the labor movement.[2]

Militancy in the labor movement

In 1917, Abílio de Nequete witnessed a series of mob violence against German immigrants in Porto Alegre, during the campaign for Brazil's entrance into the First World War. Such violence moved him and convinced him of the need to organize the population.[3] In August of the same year, he played a central role in the Popular Defense League (Liga de Defesa Popular - LDP), which was articulated during the general strike.[3] Nequete became the editor of the periodic A Epocha, LDP's agency. His status as a barber made Abílio a well-known subject with the ability to articulate personal contacts, and his interest in philosophical questions gave him a special status, as a literate worker who could be entrusted with the editorship of a newspaper.[3]

With the end of the general strike, Nequete took up a personal militant initiative in December 1917, distributing pamphlets among the lower-ranking military in an attempt to bring them closer to the workers. One of his pamphlets, called "Ao povo rio grandense", presented a very nationalistic rhetoric, which tried to sensitize the soldiers about the working class situation, suggesting that they should suspend the payment of their rents to donate 5% of the amount to the Brazilian Red Cross and to the development of aviation. The authorities considered such activity as subversive and a military police investigation was opened against Nequete.[4]

Under the impact of the Russian Revolution, Nequete started to work with the anarchists of the International Workers Union (União Operária Internacional - UOI) in 1918, conflicting with them, because some of his conceptions, such as his Spiritist faith, clashed with the Atheism of the UOI militants. Due to these frictions, Nequete decided to leave the UOI to establish, with Francisco Merino and Otavio Hengist, the Maximalist Union, in November of the same year.[5] In his memoirs, Nequete stated that, due to his Orthodox Christian origin, he had been in solidarity with Russia and that he had suffered a lot with its defeats. When the Bolsheviks took power, he came to admire Soviet Russia, adhering to its ideals.[4] The Maximalist Union is considered one of the first communist organizations in Brazil, acting among syndicates and organizing workers' strikes.[5]

In 1919, the action of the Maximalist Union in the strike of carpenters and metallurgists made the association to gain new supporters, among them Carlos Tóffolo, President of the Porto Alegre Metallurgical Union (União Metalúrgica de Porto Alegre).[5] Throughout the year, the Maximalist Union became one of the main political organizations of workers in the capital city of Rio Grande do Sul, with Nequete participating in the meetings of the Rio Grande do Sul Workers Federation (Federação Operária do Rio Grande do Sul - FORGS), then under the hegemony of the anarchists of the UOI, but also relating to the militants of the Force and Light Syndicate (Sindicato da Força e Luz), led by Orlando de Araújo Silva, a rival of the anarchists of the FORGS.[6] In the same year, Nequete became involved in a violent strike started in September by the Força e Luz workers, which was soon joined by bakers, wagoners, and telephone company workers.[7] The strikers organized a rally for the 7th, to be held in Montevideo Square, but the police prohibited it. The FORGS lawyer, in turn, consulted the Federal Constitution and considered the rally legal. When the number of the present rose to around 500, a conflict erupted between the strikers and the military brigade, which resulted in the death of a worker.[8] On the 8th, troops of the military brigade, under the orders of the governor, invaded the headquarters of the FORGS, Force and Light Syndicate and Metallurgical Union. Their leaders were imprisoned, among them Abílio de Nequete.[8][9]

After this episode, repression intensified on the organized workers of Porto Alegre. At this time, however, Abílio de Nequete and the Maximalist Union increased their presence in the FORGS. Nequete even wrote a column in the FORGS's periodical O Syndicalista, in which he wrote under the pseudonym Máximo Evidente.[9] In October 1919, Nequete also participated in a meeting of the state workers' leaderships with one of the editors of the periodical A Plebe, who had come from São Paulo to get the Gaucho militants to join an insurrection that would begin in the São Paulo capital and involve workers' organizations from various regions of the country. Abílio was given the task of traveling to the southern part of the state to decree a general strike in Pelotas and Rio Grande.[10] The insurrectionary plans failed after the explosion of a bomb at José Prol's residence in Brás neighborhood, which served as a justification for the arrest of several militants of the workers' movement and the deportation of foreign anarchists, among them Gigi Damiani and Everardo Dias.[10] The movement did not spread, and Abílio took advantage of his trip to collect addresses of Argentine Marxist publications.[11]

In 1920, Abílio de Nequete, together with Friedrich Kniestedt and Carlos Tófollo, participated in the 2nd Regional Workers Congress. In this Congress, Nequete presented a proposal for the FORGS to join the Communist International (Comintern), clashing with the anarchist Friedrich Kniestedt, who was against its approval. The proposal was rejected, so the Maximalist Union distanced itself from the FORGS and Abílio began to articulate with the communist groups that were being constituted in Brazil and the América Platina countries.[10]

In early 1921, Nequete contacted the periodic Justícia, of the Socialist Party of Uruguay (Partido Socialista del Uruguay - PSU), and he was informed of the debate about the adhesion of that group to the Communist International. Based on this, Abílio de Nequete established correspondence with Representative Celestino Mibelli, who was in favor of immediate membership, which resulted in the exchange of information and the creation of a link between the Maximalist Union and the communists of Uruguay. In a concomitant manner, Nequete established correspondence with the Rio de Janeiro Communist Group (Grupo Comunista do Rio de Janeiro), changing the name of the Maximalist Union to Porto Alegre Communist Group (Grupo Comunista de Porto Alegre). In February 1922, Abílio de Nequete was called to the Uruguayan capital to meet with a Soviet delegate for Latin America, the Russian-Argentine Alex Alexandrovsky. During his stay in Montevideo, Nequete produced a rather pessimistic report on the Brazilian labor movement in which he blamed repression and the actions of anarchist militancy for the disorganization of the labor movement. Abílio returned from Uruguay with the task of activating his contacts with the other groups in the country to found a communist party in Brazil.[12]

Between March 25 and 27, 1922, together with other nine delegates from Porto Alegre, Recife, São Paulo, Cruzeiro, Niterói and Rio de Janeiro, Abílio de Nequete participated in the foundation of the Communist Party of Brazil.[13] According to Astrogildo Pereira, Nequete had made "a great contribution to the founding of the Party", so that he suggested his name for the post of General Secretary, considering the importance of his contacts with the Uruguayan communists and with the Propaganda Agency for South America of the Communist International.[14]

Despite holding an important position within the Party, Nequete had a troubled relationship with its members:[15] after the interruption of a PCB meeting by the police, Abílio resigned from his position. In his memoirs, he stated that he was disgusted with the rent paid for the Party's headquarters, the bankruptcy of its printing shop, the disappearance of the money to be sent to the victims of the Russian scourge, and mainly with the political orientation of his comrades, considering that a good part of the PCB members were, at that moment, former anarchists and still carried with them many of their libertarian conceptions.[16] In 1923, when he had already left the post of General Secretary, the Communist Party of Uruguay asked him for a report on communism in Brazil, occasion in which he transcribed all these denunciations. In response, the executive commission of the PCB charged Octávio Brandão with preparing another report, about the attitude of Nequete, who was expelled as a traitor;[17] Brandão even called him a "charlatan, coward and braggart", and affirmed that only after his expulsion from the Party there was progress in the organization in Porto Alegre.[15] In his memoirs, however, Nequete claimed to have left communism after receiving news of British Labour Party electoral defeat, which would have convinced him that the working class was not a revolutionary class.[17]

Withdrawal from the labor movement and later years

After leaving the PCB, Nequete returned to the Republican Party of Rio Grande do Sul (Partido Republicano do Rio-grandense - PRR). In any case, in a 1924 pamphlet, even though he was out of the PCB, he called on his "communist comrades" to vote for the Republican Party in May of that year. The support would have more of a moral than official aspect, but with this, it was expected to support the release of Leopoldo Silva, arrested during the 1919 strike, besides aiming for a space in the periodic A Federação, PRR's agency, for the dissemination of communist ideas, while they did not edit their own newspaper.[18] He supported Borges de Medeiros and joined the League of Republican Workers (Liga dos Operários Republicanos) in 1925.[18]

In this period he began to show some interest in technocracy. In 1925, while writing in the newspaper A Evolução, of the League of Republican Workers, he no longer considered the workers worthy of attention. In an article in which he tried to confront the historian Aurélio Porto on the issue of the single tax, he stated, after praising the role of technicians in society, that "an examination thus dispassionate, led me to consider the technicians as the only producers, the only sustainers of everything, considering the manual workers as the same parasites". His new ideas were developed in a book released in 1926, called A technocracia: O V estado.[19] In this book, whose structure was similar to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels' The Communist Manifesto, Nequete defended the idea of an evolution of humanity in five stages, starting with ancient civilizations, passing through the feudal phase, which would be surpassed by capitalism and this, in turn, by communism, which would finally be replaced by the technocratic state, in which technicians should be responsible for the reorganization of society.[19] In 1927, he founded a Technocratic Party (Partido Tecnocrata), which, however, received only 15 votes in the state elections.[19]

Abílio de Nequete soon abandoned his profession as a barber and became a teacher at the Escola de Comércio. From the 1940s on, he devoted himself to developing the spiritual face of technocracy, Evidentism, a religious doctrine that linked spiritual evolution to the social evolution of mankind, in his Extratos evidentinos. His doctrine, however, left no followers. Nequete came to pass away in August 1960, victim of an illness.[20]

See also

References

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 159.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 160.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 161.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 162.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 163.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). pp. 163–164.

- Foster-Dulles (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). pp. 94–95.

- Foster-Dulles (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). p. 95.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 164.

- Foster-Dulles (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). p. 97.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 165.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 166.

- Foster-Dulles (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). p. 146.

- Foster-Dulles (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). pp. 147–148.

- Foster-Dulles (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). p. 149.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). pp. 166–167.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 167.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 168.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 169.

- Bartz (2008). História Social (in Portuguese). p. 170.

Bibliography

- Bartz, Frederico Duarte (2008). "Abílio de Nequete (1888-1960): os múltiplos caminhos de uma militância operária". História Social. 14/15 (in Portuguese). Campinas: IFCH/UNICAMP. pp. 157–173.

- Foster-Dulles, John W. (1980). Anarquistas e Comunistas no Brasil, 1900-1935 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira.