The captain goes down with the ship

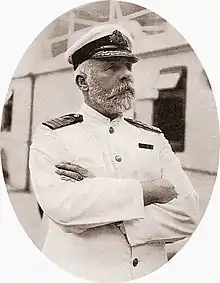

"The captain goes down with the ship" is a maritime tradition that a sea captain holds the ultimate responsibility for both the ship and everyone embarked on it, and in an emergency they will devote their time to save those on board or die trying. Although often connected to the sinking of RMS Titanic in 1912 and its captain, Edward Smith, the tradition precedes Titanic by several years.[1] In most instances, captains forgo their own rapid departure of a ship in distress, and concentrate instead on saving other people. It often results in either the death or belated rescue of the captain as the last person on board.

History

The tradition is related to another protocol from the nineteenth century: "women and children first". Both reflect the Victorian ideal of chivalry, in which the upper classes were expected to adhere to a morality tied to sacred honor, service, and respect for the disadvantaged. The actions of the captain and men during the sinking of HMS Birkenhead in 1852 prompted praise from many, due to the sacrifice of the men who saved the women and children by evacuating them first. Rudyard Kipling's poem "Soldier an' Sailor Too" and Samuel Smiles's book, Self-Help, both highlighted the valour of the men who stood at attention and played in the band as their ship was sinking.[2]

Social and legal responsibility

The tradition says that the captain should be the last person to leave their ship alive before its sinking, and if they're unable to evacuate the crew and passengers from the ship, the captain will choose not to save himself even if he has an opportunity to do so.[3] In a social context, especially as a mariner, the captain will feel compelled to take this responsibility as a social norm.

In maritime law, the ship's master's responsibility for their vessel is paramount, no matter what its condition, so abandoning a ship has legal consequences, including the nature of salvage rights.[4]

Abandoning a ship in distress may be considered a crime that can lead to imprisonment.[3] Captain Francesco Schettino, who left his ship in the midst of the Costa Concordia disaster of 2012, was not only widely reviled for his actions, but received a 16-year sentence including one year for abandoning his passengers. Abandoning ship has been recorded as a maritime crime for centuries in Spain, Greece, and Italy.[5] South Korean law may also require captains to rescue themselves last.[6] In Finland, the Maritime Law (Merilaki) states that the captain must do everything in their power to save everyone on board the ship in distress, and that unless the captain's life is in immediate danger, they shall not leave the vessel as long as there is reasonable hope that it can be saved.[7] In the United States, abandoning the ship is not explicitly illegal, but the captain could be charged with other crimes, such as manslaughter, which encompass common law precedent passed down through centuries. It is not illegal under international maritime law.[8]

Notable examples

- September 27, 1854: James F. Luce was in command of the Collins Line steamer SS Arctic when it collided with SS Vesta off the coast of Newfoundland. Captain Luce was able to escape the wreck and swim to the surface after initially going down with the ship. He was rescued two days later drifting on wreckage of the same paddle-wheel box that killed his youngest son Willie.[9]

- September 12, 1857: William Lewis Herndon was in command of the commercial mail steamer Central America when it encountered a hurricane. Two ships came to the rescue, but could save only a fraction of the passengers, so Captain Herndon chose to remain with the rest.

- September 17, 1894: Captain Deng Shichang, in command of the Zhiyuan during the Battle of the Yalu River, went down with the ship and refused to be rescued, after the ship was struck by a Japanese shell, causing a massive explosion.

- March 27, 1904: Commander Takeo Hirose, in command of the blockship Fukui Maru at the Battle of Port Arthur, went down with the ship while searching for survivors, after the ship sustained a direct strike from Russian coastal artillery, causing it to explode.

- April 13, 1904: Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov of the Imperial Russian Navy went down with his ship, Petropavlovsk, after his ship hit a Japanese naval mine during the early phase of the Siege of Port Arthur.

- April 15, 1912: Captain Edward Smith, in command of RMS Titanic when it sank in the North Atlantic Ocean after striking an iceberg, was seen returning to the bridge just before the ship began its final plunge.[10] There are conflicting accounts of Smith's death. Initial rumours suggest that Smith shot himself,[11] while others suggest that he died on the bridge when it was engulfed by the sea.[12][13] Reliable[14] accounts suggest that Smith and Thomas Andrews jumped overboard from the bridge as the ship sank, and subsequently perished in the water, possibly near lifeboat Collapsible B. An unknown swimmer who was thought to have been Smith, cried out, "All right boys. Good luck and God bless you", and cheered the occupants on saying "Good boys! Good lads!" before dying.[15][16]

- August 26, 1914: Captain Zimro Moore was in command of the SS Admiral Sampson, a U.S. cargo and passenger steamship, when it was rammed by the steamship, Princess Victoria, in fog near Seattle, Washington. He refused to leave the ship and with other crew managed to help most passengers to safety on the Princess Victoria. He went down with the ship.

- December 30, 1917: The troop transport HMT Aragon was torpedoed outside Alexandria, Egypt, after being ordered by Senior Naval Officer on depot ship HMS Hannibal to turn around when having just entered the entrance channel. Confusion over mine clearance and communication procedures resulted in loss of approximately six hundred and ten men from Aragon and HMS Attack, her escort, which had just rescued approximately seven hundred men from Aragon. Captain Francis Bateman had overseen the full evacuation and is reported as shouting his last words demanding an inquiry as to why he was ordered out to sea after reaching safe channel. He then jumped overboard going down with his ship. Both ships were torpedoed by the same German U-boat, SM UC-34, within less than thirty minutes.

- May 27, 1918: HMT Leasowe Castle was torpedoed and sunk carrying ~2900 troops and ship's company 104 miles (167 km) out of Alexandria. Captain Edward John Holl went down with his ship with the exhortation to his crew "...they must be saved!"[17]

- May 30, 1918: When the Italian steamer Pietro Maroncelli was torpedoed by the German submarine UB-49 and started to sink, Italian Rear Admiral Giovanni Viglione, who was on board as the convoy commodore, ordered all the survivors into the lifeboats, then chose to stay aboard and to go down with the ship.[18]

- October 25, 1927. Captain Simone Gulì went down with his ship SS Principessa Mafalda off the coast of Brazil, five hours after a propeller shaft fractured and damaged the hull; there were 314 fatalities out of the 1,252 passengers and crew on board the ship.

- June 27, 1940. When Italian submarine Console Generale Liuzzi was forced to surface by British destroyers in the Mediterranean, her commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Lorenzo Bezzi, ordered his crew to abandon ship and then scuttled the submarine, going down with it.

- October 21, 1940. During the Action off Harmil Island, Italian destroyer Francesco Nullo was disabled by HMS Kimberley and later finished off by Royal Air Force (RAF) Blenheim bombers. Her commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Costantino Borsini, chose to go down with his ship; seaman Vincenzo Ciaravolo, his attendant, chose to follow him.

- November 5, 1940: German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer encountered Allied Convoy HX 84 in the North Atlantic. The convoy consisted of 38 merchant ships escorted by HMS Jervis Bay, an ocean liner newly armed with guns of 1890s design. Her captain, Edward Fegen VC, signalled the convoy to scatter, and attacked the enemy. Jervis Bay was hopelessly outranged and outgunned, and was sunk; her captain and many of her crew went down with her. The sacrifice bought enough time for 31 of the convoy to make it to safety.

- May 24, 1941: During the Battle of the Denmark Strait, HMS Hood suffered a direct hit and magazine explosion, which sank the ship in three minutes. Only three people survived the disaster. One of the survivors, Ted Briggs, said in interviews after the sinking that Vice Admiral Lancelot Holland was last seen sitting in his chair, in utter dejection, making no attempt to escape from the sinking ship.

- May 27, 1941: Captain Ernst Lindemann of the German battleship Bismarck was said to be with his combat messenger, a leading seaman, and apparently trying to persuade his messenger to save himself. In this account, his messenger took Lindemann's hand and the two walked to the forward flagmast. As the ship turned over, the two stood briefly to attention, then Lindemann and his messenger saluted. As the ship rolled to port, the messenger fell into the water. Lindemann continued his salute while clinging to the flagmast, going under with the ship.[19][20]

- December 10, 1941: Admiral Sir Tom Phillips and Captain John Leach went down with HMS Prince of Wales after an attack by Japanese warplanes off the coast of Pahang, British Malaya.

- February 28, 1942: Rear Admiral Karel Doorman was killed in action when his flagship HNLMS De Ruyter was torpedoed in the Battle of the Java Sea. Part of the crew was rescued before the sinking, but the Dutch admiral chose to go down with the ship. Captain Lieutenant Eugène Lacomblé also died in the sinking.

- June 5, 1942: Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, on board the aircraft carrier Hiryū, insisted on staying with the stricken ship during the Battle of Midway. The ship's commander, Captain Kaku, followed his example. Yamaguchi refused to allow his staff officers to stay with them. Yamaguchi and Kaku were last seen on the bridge of the stricken carrier waving to the crew who were abandoning ship.[21] In addition, Captain Ryusaku Yanagimoto chose to remain with his ship Sōryū when it was scuttled after being destroyed in the same battle.

- September 27, 1942. Captain Paul Buck of SS Stephen Hopkins, a lightly-armed US liberty ship, went down with his ship after fighting German commerce raider Stier to a standstill. Captain Buck was posthumously awarded the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal.

- February 7, 1943: Commander Howard W. Gilmore, captain of the American submarine USS Growler, gave the order for crew to "clear the bridge" and leave the exposed deck of the submarine, as his crew was being attacked by a Japanese gunboat. Two men had been shot dead; Gilmore and two others were wounded. After all others had entered the sub and Gilmore found that time was critically short, he gave his last order: "Take her down." The executive officer, hearing his order, closed the hatch and submerged the crippled boat, saving the rest of the crew from the attack of the Japanese convoy escort. Commander Gilmore, who was never seen again, received the Medal of Honor posthumously for his "distinguished gallantry", making him the second submariner to receive this award.

- November 19, 1943: Captain John P. Cromwell went down on the sinking sub USS Sculpin.

- October 24, 1944: Rear Admiral Toshihira Inoguchi[22] chose to go down with the Japanese battleship Musashi, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, even though he could have escaped. Over half of the ship's crew, 1,376 of 2,399, were rescued.

- October 25, 1944: Commander Ernest E. Evans, in the Battle off Samar, a part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, captained Fletcher Class destroyer Johnston in a torpedo attack until it was sunk by a Japanese force that was vastly superior in number, firepower, and armor. Evans did not survive. Evans posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

- November 29, 1944: Captain Toshio Abe went down with the Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano after she was torpedoed by USS Archerfish.

- December 24, 1944: Captain Charles Limbor went down with the Léopoldville after it was torpedoed and sank by U-486 5 miles from Cherbourg.

- April 7, 1945: Vice Admiral Seiichi Itō, the fleet admiral, and Captain Kosaku Aruga went down with the Japanese battleship Yamato during Operation Ten-Go.

- December 30, 1950: Luis González de Ubieta (born 1899), exiled Admiral of the Spanish Republican Navy, went down with his ship. He refused to be rescued when Chiriqui, a merchant vessel under his command, sank in the Caribbean Sea not far from Barranquilla.[23]

- January 10, 1952: After his ship was struck by a pair of rogue waves, Captain Kurt Carlsen of the SS Flying Enterprise remained aboard his ship once her passengers and crew had been evacuated in order to oversee attempts to tow the crippled vessel into port. He was eventually joined by Ken Dancy, a member of the salvage tug's crew. When the time came to abandon ship, Carlsen said to Dancy that they would jump together; Dancy refused, saying he should go first so that Carlsen could be the last to leave the ship. The Flying Enterprise sank 48 minutes later.

- July 26, 1956: Piero Calamai, the captain of the Italian liner Andrea Doria, after satisfying himself that all 1,660 passengers and crew had been safely evacuated following a collision with the MS Stockholm had determined to go down with the ship to atone for his errors leading to the disaster, which killed 46 people. During his supervision of the rescue operation, one of the largest in maritime history, Calamai turned to one of his officers and said softly, "If you are saved, maybe you can reach Genoa and see my family. ... Tell them I did everything I could." His officers finally convinced him to reluctantly board a lifeboat by refusing to leave him behind; nevertheless, Calamai made certain he was the last person off his doomed ship.[24][25] Captain Calamai, who never commanded another vessel, reportedly asked repeatedly on his deathbed in 1972, "Are the passengers safe? Are the passengers off?".[26]

- December 9, 1971: Captain Mahendra Nath Mulla, MVC, the captain of the Indian frigate INS Khukri, went down with the ship after it was attacked by a submarine in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. At least 194 members of the crew died in the sinking, which reportedly took two minutes.

- November 10, 1975: Captain Ernest M. McSorley, of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald (a Great Lakes freighter), perished, along with all other hands in a massive November storm on Lake Superior. The captain of another freighter (the Arthur M. Anderson) messaged the Fitzgerald around 7:10 p.m. to see how matters were going. McSorley answered back, "We're holding our own." With that, the Fitzgerald disappeared from radar.

- September 28, 1994: Captain Arvo Andresson sank with MS Estonia off the coasts of Estonia and Finland. Of the 989 people on board, 137 were rescued and 95 were later found dead in freezing waters or rafts.

- July 19, 1996: Lieutenant Commander Parakrama Samaraweera, RSP, the captain of the Sri Lanka Navy ship SLNS Ranaviru, went down with the ship after it was attacked by LTTE during the first battle of Mullaitivu. Commander Samaraweera was last seen on the bridge firing a rifle. His body was never recovered.[27]

- October 29, 2012: Captain Robin Walbridge of the Bounty, a replica of HMS Bounty, stayed on the ship until it capsized during Hurricane Sandy. Walbridge and one crew member died, while the fourteen crew members who made it to liferafts survived.[28][29] Captain Walbridge was never found.[30]

- October 2, 2015: Captain Michael Davidson, master of the cargo ship El Faro, was recorded on the voyage data recorder encouraging the ship's helmsman, not moving due to fear and exhaustion, to join him in abandoning the vessel, before the recording ended with both still on the bridge of the sinking ship.

Counter-examples

In some cases the captain may choose to scuttle the ship and escape danger rather than die as it sinks. This choice is usually available only if the damage does not immediately imperil a vast portion of the ship's company and occupants. If a distress call was successful and the crew and occupants, the ship's cargo, and other items of interest are rescued, then the vessel may not be worth anything as marine salvage and be allowed to sink. In other cases a military organization or navy might wish to destroy a ship to prevent it being taken as a prize or captured for espionage, such as occurred in the USS Pueblo incident. Commodities and war materiel carried as cargo might also need to be destroyed to prevent capture by the opposing side.

In other cases a captain may decide to save themselves to the detriment of their crew, the vessel, or its mission. A decision that shirks the responsibilities of the command of a vessel will usually bring upon the captain a legal, criminal, or social penalty, with military commanders often facing dishonor.

- July 17, 1880: The captain and crew of SS Jeddah abandoned the ship and their passengers in a storm expecting it would sink, but the ship was found with all passengers alive three days later. A key part of Joseph Conrad's 1899–1900 novel Lord Jim is based on this incident; Conrad had been a captain in the merchant marine before turning to writing.

- September 8, 1934: When a fire broke out on the SS Morro Castle, First Officer William Warms, in command after the death of Captain Robert Wilmott, led the crew in abandoning ship. 137 people died, mostly passengers.

- September 10, 1941: When the German submarine U-501 was forced to surface alongside a Canadian corvette, Korvettenkapitän Hugo Förster surrendered himself by jumping onto the Canadian ship. The First Watch Officer took over and had the U-boat scuttled just as the Canadians boarded. One Canadian and 11 Germans died.

- October 1944: Lieutenant Commander Richard O'Kane of the USS Tang (SS-306) was one of nine survivors of the Tang during its sinking by its own torpedo. With his submarine scuttled, he was one of three survivors to have made it off the bridge and up to the surface, before being captured by a Japanese destroyer crew later that morning. O'Kane was at first secretly held captive at the Ōfuna navy detention center, then later moved to the regular army Omori POW camp. Following his release, O'Kane was awarded the Medal of Honor for "conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity" during his submarine's final operations against Japanese shipping.

- November 12, 1965: When a fire broke out aboard SS Yarmouth Castle, Captain Byron Voustinas was on the first lifeboat, which had only crew and no passengers aboard. 90 people died.

- April 7, 1990: Having been erroneously informed the ship was evacuated, Captain Hugo Larsen abandoned MS Scandinavian Star after arson caused the ship to burn. 158 people died.

- August 3–4, 1991: Captain Yiannis Avranas of the cruise ship MTS Oceanos abandoned ship without informing passengers that the ship was sinking. All 571 people on the ship survived. A Greek board of inquiry found Avranas and four officers negligent in their handling of the disaster.

- September 26, 2000: Captain Vassilis Giannakis and the crew abandoned the MS Express Samina after the ship hit the rocks off the Portes Inlets. 82 people died. The captain was sentenced to 16 years in prison while the first officer received a 19-year sentence.

- January 13, 2012: Captain Francesco Schettino abandoned his ship before hundreds of passengers had been evacuated during the Costa Concordia disaster. 32 people died in the accident. Schettino was sentenced to 16 years in prison for his role in the disaster.

- April 16, 2014: Captain Lee Joon-seok abandoned the South Korean ferry MV Sewol. The captain and much of the crew were saved, while hundreds of students from Danwon High School embarked for their trip remained in their cabins, according to instructions provided by the crew.[31][6] Many passengers apparently remained on the sinking vessel and died. Following this incident, the captain was arrested and put on trial beginning in early June 2014, when video footage filmed by some survivors and news broadcasters showed him being rescued by a coast guard vessel. Orders to abandon ship never came, and the vessel sank with all life rafts still in their stowage position. The captain was subsequently sentenced to 36 years in prison for his role in the deaths of the passengers, and was also given a life sentence, after being found guilty of murder of the 304 passengers that did not survive.

- June 1, 2015: The Chinese captain of the river cruise ship Dong Fang Zhi Xing left the ship before most passengers were rescued. In the end, 442 deaths were confirmed with 12 rescued among 454 on board.[32]

Extended or metaphorical use

When used metaphorically, the "captain" may be simply the leader of a group of people, "the ship" may refer to some other place that is threatened by catastrophe, and "going down" with it may refer to a situation that implies a severe penalty or death. It is common for references to be made in the case of the military and when leadership during the situation is clear. So when a raging fire threatens to destroy a mine, the mine's supervisor, the "captain", may perish in the fire trying to rescue their workers trapped inside, and acquaintances might say that they went down with their ship or that they "died trying".

In aviation

The concept has been explicitly extended in law to the pilot in command of an aircraft, in the form of laws stating that they "[have] final authority and responsibility for the operation and safety of the flight".[33] Jurisprudence has explicitly interpreted this by analogy with the captain of a sea vessel.

This is particularly relevant when an aircraft is forced to ditch in the ocean and becomes a floating vessel that will almost certainly sink. For example, following the crash of US Airways Flight 1549 into the Hudson River in 2009, pilot in command Chesley Sullenberger was the last person to exit the partially submerged aircraft, and performed a final check for any others on board before doing so. All 155 passengers and crew survived.[34][35][36]

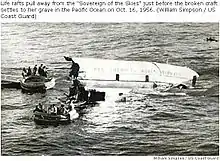

Similarly, on October 16, 1956, Pan Am Flight 6 was a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser (en route from Honolulu to San Francisco) that was forced to ditch in the Pacific Ocean due to multiple engine failures. The airliner broke apart when one of its wings collided with a wave swell. Airline Captain Richard N. Ogg was the last to exit the airplane during the successful mid-ocean ditching and rescue of all 31 on board by the US Coast Guard cutter USCGC Pontchartrain.[37] The airplane fuselage sank with no one on board a few minutes later.[37]

Kohei Asoh, the captain of a Douglas DC-8 conducting Japan Air Lines Flight 2, gained notoriety for his honest assessment of his mistake (the "Asoh defense") in the 1988 book The Abilene Paradox. Asoh was the pilot in command during the 1968 accidental ditching in San Francisco Bay a few miles short of the runway.[38] With the plane resting on the shallow bottom of the bay, he was the last one of the 107 occupants to exit the airplane; all survived with no injuries.[39]

In academia

After a major sexual assault scandal at Baylor University, the university fired President Kenneth Starr and appointed him chancellor. A week later, Starr resigned as chancellor and "willingly accepted responsibility" for the actions at Baylor that "clearly fell short". He stated that his resignation for the scandal was "a matter of conscience", and said, "The captain goes down with the ship."[40] He indicated that his resignation was necessary even though he "didn't know what was happening".

See also

References

- John, Alix (1901). The Night-hawk: A Romance of the '60s. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. pp. 249.

...for, if anything goes wrong a woman may be saved where a captain goes down with his ship.

- Synnott, Anthony (2016). Re-Thinking Men: Heroes, Villains and Victims. Taylor and Francis. p. 33. ISBN 978-1317063940.

- "Must a captain be the one-off a sinking ship?". BBC News. January 18, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- A Digest of Maritime Law Cases, from 1837 to 1860, Shipping Law Cases. H. Cox. 1865. p. 1.

- Hetter, Katia (January 19, 2012). "In a cruise ship crisis, what should happen?". CNN. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Drew, Christopher; Mouawad, Jad (April 19, 2014). "Breaking Proud Tradition, Captains Flee and Let Others Go Down With Ship". The New York Times. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- "Merilaki 6 Luku 12 §. 15.7.1994/674 - Ajantasainen lainsäädäntö". FINLEX, database of Finnish Acts and Decrees (in Finnish). 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Longstreth, Andrew (January 20, 2012). "Cowardice at sea is no crime – at least in the U.S." Reuters. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- Shaw, David (2002). The Sea Shall Embrace Them. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 256. ISBN 9780743235037.

- "Day 9 - Testimony of Edward Brown (First Class Steward, SS Titanic)". British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. May 16, 1912. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- "Capt. Smith Ended Life When Titanic Began To Founder (Washington Times)". Encyclopedia Titanica. April 19, 1912. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Bartlett, W.B. (2011). Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell, the Survivors' Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4456-0482-4.

- Spignesi, Stephen (2012). The Titanic for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 207. ISBN 9781118206508. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- "Day 14 - Testimony of Harold S. Bride, recalled". United States Senate Inquiry. May 4, 1912. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- A Night to Remember

- On a Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the RMS Titanic by Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton & Bill Wormstedt. Amberley Books, March 2012. p 335

- Knight, Edward Frederick (1920). The Union-Castle and the War 1914-1919. Union-Castle Mail Steamship Company. p. 32.

- "Steamer Pietro Maroncelli - Ships hit by U-boats - German and Austrian U-boats of World War One - Kaiserliche Marine - uboat.net". uboat.net.

- Grützner, Jens (2010). Kapitän zur See Ernst Lindemann: Der Bismarck-Kommandant – Eine Biographie [Captain at Sea Ernst Lindemann: The Bismarck-Commander – A Biography] (in German). Zweibrücken: VDM Heinz Nickel. p. 202. ISBN 978-3-86619-047-4.

- McGowen, Tom (1999). Sink the Bismarck: Germany's Super-Battleship of World War II. Brookfield, Connecticut: Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-7613-1510-0 – via Archive.org.

- Lord, Walter (1967). Incredible Victory. New York: Harper and Row. pp. 249–251. ISBN 1-58080-059-9.

- "Toshihira Inoguchi". World War II Database. 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- García Fernández, Javier (coord.) (2011). 25 militares de la República; "El Ejército Popular de la República y sus mandos profesionales. Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa.

- Andrews, Evan (May 8, 2023). "The Sinking of Andrea Doria". History.

- Pecota, Samuel (January 18, 2012). "In Andrea Doria wreck, a captain who shone". CNN.

- Rasmussen, Frederick N. (February 26, 2012). "Some captains show bravery, others cowardice in face of maritime disasters". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- "FEATURESGentle giant who fought to the death". The Island. July 12, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- Ware, Beverley (February 15, 2013). "Witness recounts Claudene Christian's last minutes on Bounty". The Chronicle Herald. Halifax, Nova Scotia. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- "Bounty crew member's body found, captain still missing". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. October 29, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- "Coast Guard suspends search for missing captain of HMS Bounty" (Press release). United States Coast Guard. November 1, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- "참사 2주째 승무원도 제대로 파악 안돼" [Exact Number of Crew still not known 2 weeks after the ferry disaster]. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). April 20, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- "Yangtze River Ship Captain Faces Questions on Sinking". The Wall Street Journal. June 2, 2015.

- "Title 14 Chapter I Subchapter A Part 1 §1.1". Code of Federal Regulations. 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Sturcke, James (January 16, 2009). "Chesley 'Sully' Sullenberger: US Airways crash pilot". The Guardian. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- McFadden, Robert D. (January 16, 2009). "Pilot Is Hailed After Jetliner's Icy Plunge". The New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Goldman, Russell (January 15, 2009). "US Airways Hero Pilot Searched Plane Twice Before Leaving". ABC News. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- This Day in Aviation, 16 October 1956, 2016, Bryan R. Swopes

- Silagi, Richard (March 9, 2001). "The DC-8 that was too young to die". Airliners.net. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- "107 On Board Uninjured As Jetliner Lands In Bay". Toledo Blade. AP. November 22, 1968. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- "Starr won't be Baylor chancellor, will teach". ESPN.com. June 1, 2016.