Adyton

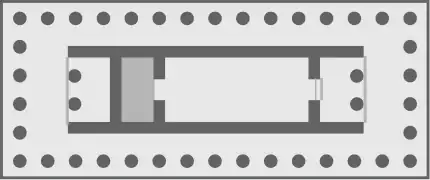

The adyton (Ancient Greek: ἄδῠτον [ádyton], 'innermost sanctuary, shrine', lit. 'not to be entered') or adytum (Latin) was a restricted area within the cella of a Greek or Roman temple. The adyton was frequently a small area at the farthest end of the cella from the entrance; at Delphi it measured just 9 by 12 feet (2.7 by 3.7 m). The adyton often would house the cult image of the deity.

Adyta were spaces reserved for oracles, priestesses, priests, or acolytes, and not for the general public. Adyta were found frequently associated with temples of Apollo, as at Didyma, Bassae, Clarus, Delos, and Delphi, although they were also said to have been natural phenomena (see the story of Nyx). Those sites often had been dedicated to deities whose worship preceded that of Apollo and may go back to prehistoric eras, such as Delphi, but who were supplanted by the time of Classical Greek culture.[1]

In modern usage, the term is sometimes extended to similar spaces in other cultural contexts, as in Egyptian temples or the Western mystery school, Builders of the Adytum.

The term abaton (Koinē Greek: ἄβατον, [ábaton], 'inaccessible') or avato (Greek: άβατο, [ˈavato]) is used in the same sense in Greek Orthodox tradition, usually of the parts of monasteries accessible only to monks or only to male visitors.

Truncated variants of the term, adyt or adyte (plural: adites, addittes, adyts) are found in English as early as the late 16th century. By the early 19th century, the term acquired a figurative meaning, referring to the innermost parts of any structure or of the human psyche.[2]

See also

- Holy of Holies

- Inner sanctum

- Sanctuary

- Sanctum sanctorum

- Mahavira Hall and Hondo, sometimes translated as adytum

Sources

- Broad, William J. The Oracle: The lost secrets and hidden messages of ancient Delphi. Penguin Press, 2006

References

- Herbert William Parke, The Delphic Oracle, v. 1, p. 3. "The foundation of Delphi and its oracle took place before the times of recorded history. It would be foolish to look for a clear statement of origin from any ancient authority, but one might hope for a plain account of the primitive traditions. Actually this is not what we find. The foundation of the oracle is described by three early writers: the author of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, Aeschylus in the prologue to the Eumenides, and Euripides in a chorus in the Iphigeneia in Tauris. All three versions, instead of being simple and traditional, are already selective and tendentious. They disagree with each other basically, but have been superficially combined in the conventional version of late classical times."Parke goes on to say, "This version [Euripides] evidently reproduces in a sophisticated form the primitive tradition which Aeschylus for his own purposes had been at pains to contradict: the belief that Apollo came to Delphi as an invader and appropriated for himself a previously existing oracle of Earth. The slaying of the serpent is the act of conquest which secures his possession; not as in the Homeric Hymn, a merely secondary work of improvement on the site. Another difference is also noticeable. The Homeric Hymn, as we saw, implied that the method of prophecy used there was similar to that of Dodona: both Aeschylus and Euripides, writing in the fifth century, attribute to primeval times the same methods as used at Delphi in their own day. So much is implied by their allusions to tripods and prophetic seats."Continuing on p. 6, "Another very archaic feature at Delphi also confirms the ancient associations of the place with the Earth goddess. This was the Omphalos, an egg-shaped stone which was situated in the innermost sanctuary of the temple in historic times. Classical legend asserted that it marked the 'navel' (Omphalos) or center of the Earth and explained that this spot was determined by Zeus who had released two eagles to fly from opposite sides of the earth and that they had met exactly over this place".On p. 7 he writes further, "So Delphi was originally devoted to the worship of the Earth goddess whom the Greeks called Ge, or Gaia. Themis, who is associated with her in tradition as her daughter and partner or successor, is really another manifestation of the same deity: an identity which Aeschylus himself recognized in another context. The worship of these two, as one or distinguished, was displaced by the introduction of Apollo. His origin has been the subject of much learned controversy: it is sufficient for our purpose to take him as the Homeric Hymn represents him—a northern intruder—and his arrival must have occurred in the dark interval between Mycenaean and Hellenic times. His conflict with Ge for the possession of the cult site was represented under the legend of his slaying the serpent."

- OED, s.v., adyt, n., entry 3059.