Abbey of Notre Dame aux Nonnains

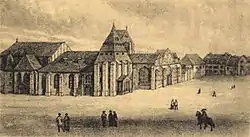

The Abbey of Notre Dame aux Nonnains (French: Abbaye de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains: Abbey of Our Lady of the Nuns), also called the Royal Abbey of Our Lady of Troyes (French: Abbaye royale de Notre-Dame de Troyes), was a convent founded before the 7th century in Troyes, France. The non-cloistered canonesses became wealthy and powerful in the Middle Ages. In 1266–68 they defied the pope and used force to delay construction of the collegiate Church of St Urbain. They were excommunicated as a result. Later the abbey adopted a strictly cloistered rule and the nuns became impoverished. Work started on building a new convent in 1778 but was only partially completed before the French Revolution (1789–99). The abbey was closed in 1792 and the church was demolished. The convent became the seat of the prefecture of Aube.

Abbaye de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains | |

| |

Location within France | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Abbaye royale de Notre-Dame de Troyes |

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | c. 655 |

| Disestablished | 1790 |

| Diocese | Troyes |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Saint Luzon, Bishop of Troyes (651–656) |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Destroyed |

| Site | |

| Location | Troyes, France |

| Coordinates | 48.297337°N 4.078266°E |

Early years

According to legend the abbey of Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains has its origins in the Gallo-Roman era.[1] Legend says that in the 3rd century a women's college charged with maintaining the sacred fire of a pagan temple was built under the walls of the city of Tricasses, headed by a wealthy princess of royal blood.[2] The legends say that Saint Savinien converted them to Christianity around the year 259. Others say that Leuconius, 18th Bishop of Troyes, converted them in 651, quoting a breviary printed by the abbess Maria du Moutier in 1543.[3]

It seems likely that the convent was founded before the 7th century.[4] Tradition says that Saint Leuçon, Bishop of Troyes from 651 to 656, was buried there.[5] Saint Leuçon intended the convent to house widows and young women who had been converted to Christianity. They lived in a community, at first as non-cloistered canonesses.[2] The convent was dedicated to the Virgin of the Assumption under the name of Notre-Dame "aux Nonnains".[2]

The first firm evidence of the convent comes from a letter written by Alcuin (c. 735–804), who had been named abbot of Saint-Loup de Troyes in 782 in the time of Charlemagne (c. 748–814), and who wrote a letter to the abbess of the convent of Notre-Dame thanking her for a cross that she had sent. Her name is unknown.[4] A second proof of the convent's existence comes from a letter written around 1140 to one of the nuns by Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153). Despite reforms that had been instituted there, she wanted to leave the convent and retire into solitude. Bernard wrote to dissuade her from this course.[6] Over the years the convent accumulated unusual immunities and privileges in Troyes.[2]

Medieval convent

On 23 July 1188, during the Troyes Fairs, most of the buildings of the city were destroyed by a violent fire, including the cathedral and the convent of Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains. Many nuns died and all the records were lost. Henry II, Count of Champagne (1166–97) rebuilt the convent, and the Bishop Manassès II de Pougy (r. 1181–90)[lower-alpha 1] renewed the privileges of the nuns.[1] The new convent was built of chalk and mud, and was several stories high.[9] A document from the 13th century shows that the abbess was not just concerned with spiritual values, but was dedicated to maintaining the property, wealth and privileges of the abbey.[10]

Pope Urban IV (c. 1195–1264) was born in Troyes. He asked the Sisters of Notre Dame aux Nonnains to give him the location around his father's cobbler's shop as the site for a collegiate Church of St Urbain. In 1266, and again in 1268, the nuns interrupted the work and sacked the building.[2] In 1268 the nuns hired armed men who prevented the Archbishop of Tyre and the Bishop of Auxerre from blessing the new cemetery.[11] The abbess Ode de Pougy disrupted the church ceremony with her nuns, retainers and followers and drove the prelate out into the road.[8] In March 1269 the pope excommunicated the abbess and several associates who had assisted her.[12]

The nuns finally submitted to the pope in 1283. In 1361 King John II of France (1319–64) confirmed the donations of Henry II of Champagne. In 1448 one of the nuns became a mother. This started a series of acts of procedure, information and excommunication. The underlying cause was a struggle between the bishop and the abbess.[2]

Church

The abbey church was also a parish church under the patronage of Saint-Jacques-aux-Nonnains.[5] The Église Saint Jacques was famous for its 15th century portal in Flamboyant Gothic style, from which it was called "Saint Jacques au Beau Portail". At 72 metres (236 ft) in length it was the second largest church in Troyes after the cathedral. It was divided into one part for the parishioners and another for the nuns. An inventory drawn up before the contents were sold on 15 September 1792 shows that the church was richly furnished. The external choir, open to the parishioners, had a high altar with twisted and carved columns, wood panels and statues, all of gilded wood. It was furnished with upholstered benches and decorated with a crystal chandelier. The interior choir reserved for the nuns was surrounded by two rows of stalls surmounted by paneling, and was decorated with six medium-sized paintings and four statues. Small chapels on the north side were also decorated with paintings.[10]

Cloistered rule

The abbess Catherine de Courcelles began a cloistered rule under of the Order of Saint Benedict in 1518. In 1542 the abbess Claudée de Choiseul, daughter of Choiseul Praslain, Marshal of France, introduced a stricter regime. She had grilles placed in the parlors and church to enforce the cloister.[2] By the end of the 17th century the medieval church and convent buildings were seriously dilapidated. Various partial renovations were undertaken.[9] In 1721 the regent Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674–1723) relieved the nuns of some of their debts. In 1724 the abbess Marie-Madeleine-Margeurite de la Chaussée d’Eu d’Arrêt explained the poor state of the finances of the monastery to King Louis XV of France (1710–74), who placed the abbey under his protection.[2]

The abbess Françoise-Lucie de Montmorin described the poor state of the monastery to King Louis XVI of France (1754–93), who in 1776 agreed to make a large donation for its reconstruction.[2] The architect Louis de La Brière of Paris was assigned the work. On 30 April 1778 the first stone was laid with great pomp by the Marquise de Montmorin, acting for the king's aunt Victoire (1733–99).[9] Funding ran out in 1781 and the work stopped. Of the four buildings planned by La Brière only the north one was completed. The building looking over the Place Notre-Dame was incomplete, and the two projecting wings were reduced in size.[13]

French Revolution and later history

During the French Revolution (1789–99) the abbey was closed in 1790 and sold in September 1792.[5] The 27 remaining nuns remained until the convent was confiscated in 1792. The furniture of the convent and the church were then auctioned. The buildings were not sold, but were used for storing food and wood, as rest houses for troops, then as a museum, library and archive. Precious objects and books from nearby churches and abbeys were stored in the attics.[13] In 1794 the state ceded part of the former abbey to the newly formed prefecture of the Aube. The facade of the rather austere former convent was renovated in 1838, and the building has gone through various modifications since then.[14]

Starting in 1794 the adjoined churches were demolished and their stones used to start building a hall for storing grain. This was not completed, and in 1816 the walls were demolished.[15] Some of the medieval buildings remained in the reign of Louis Philippe (r. 1830–48).[13] The large area to the north and west of the church held the Notre-Dame cemetery, where the dead of the abbey and the parish were buried.[15] A corn exchange was built on the site between 1837 and 1841, but was torn down and replaced by a smaller iron and brick building in 1896.[16] Today the site of the ancient abbey, the churches of Saint-Jacques-au-Beau-Portail and Notre-Dame and the cemetery have become the place de la Libération. The abbey gardens are now the gardens of the prefecture.[1]

Abbesses

Records of the abbesses before the great fire of 1188 are fragmentary. Abbesses since then were:[7]

- Gertrude II (1183–1211)

- Adélide II de Vendeuvre (1211–31), daughter of countess of Sens

- Adélide III (1213–49), daughter of Geoffrey of Villehardouin

- Mathilde I de Valières (1249–62)

- Hermengarde du Chastel (1262)

- Isabelle I de Chasteau-Villain (1262–64), dame de Barbery-Saint-Sulpice

- Ode I de Pougy (1264–72), niece of Manassès II of Troyes

- Isabelle II (1272–75)

- Ode II (1275–84)

- Jeanne I de Gastebled (1284–89)

- Herminie (1289–90)

- Isabelle III de Saint-Phal (1290–93)

- Gille de Veauxjean (1293–97)

- Isabelle IV de Saint-Phal (1297–1314)

- Isabelle V de Saint-Phal (1314–28)

- Mathilde II d'Anglure (1328–49)

- Béatrix (1349–52)

- Helvis de Troyes (1355–57)

- Marie I de Saint-Phal (1357–68)

- Jeanne II de Ricey (1368–69)

- Marguerite de Saint-Phal (1369–1409)

- Blanche de Brie (1410–1438)

- Jeanne III de Broies (1438)

- Jeanne IV de Vézelize (died 1447)

- Isabelle VI de Neuville (1448)

- Huguette de Baissy (died 1465)

- Catherine I de Lusigny (1465–75)

- Isabelle VII de Rochetaillée (1475–80)

- Claudée de Bercenay (1480–82) nominal Abbess

- Catherine II de Courcelles (1482–1519)

- Marie II de Moutier (1519–42)

- Marie III de Foolz (1543–57)

- N. Manthelon (1557–60)

- Marie IV de Luxembourg (1560–97) daughter of Charles I, Count of Ligny

- Louise I de Luxembourg (1597–1602), daughter of François, Duke of Piney-Luxembourg

- Louise II de Dinteville (1602–17), daughter of Guillame de Dinteville

- Claudée de Choiseul de Praslains (died 1667), daughter of Charles de Choiseul de Praslains, Marshal of France

- Anne de Choiseul de Praslains (1667–88), daughter of Charles de Choiseul de Praslains

- Louise-Scolastique le Pelletier (from 1688)

- Marie-Madeleine-Margeurite la Chaussée (from 1698)

- Françoise-Lucie de Montmorin (from 8 August 1756)

Notes

- Manassès II (de Pougy), Bishop of Troyes, was the uncle of Ode de Pougy, abbess from 1264 to 1272.[7] She was known for her resistance to the construction of the Church of St Urbain.[8]

- Demessmacker, Renaud & Morin, p. 1.

- Schweitzer.

- Coffinet 1852, p. 2.

- Coffinet 1852, p. 6.

- Abbaye de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains – BnF.

- Coffinet 1852, p. 7.

- Coffinet 1852b, p. 243.

- Boutiot 1870, pp. 377–378.

- Demessmacker, Renaud & Morin, p. 2.

- Grosdoit-Artur 2002.

- Kane 2010, p. 55.

- Coffinet 1852, p. 22.

- Demessmacker, Renaud & Morin, p. 3.

- Demessmacker, Renaud & Morin, pp. 4–6.

- Demessmacker, Renaud & Morin, p. 7.

- Demessmacker, Renaud & Morin, p. 8.

Sources

- "Abbaye de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains" (in French). BnF. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- Boutiot, Théophile (1870), Histoire de la ville de Troyes et de la Champagne méridionale (in French), A. Aubry, retrieved 2015-12-17

- Coffinet (1852), Sceau de l'abbaye de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains de Troyes (douzième siècle) (in French), on souscrit chez M. A. Forgeais, retrieved 2015-12-17

- Coffinet (1852b), Société de sphragistique de Paris (in French), retrieved 2015-12-17

- Demessmacker, Martine; Renaud, Dominique; Morin, Louis. "De l'Abbaye Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains à la Préfecture de l'Aube" (PDF) (in French). Préfecture de l’Aube. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-18.

- Grosdoit-Artur, H. (2002), Notre Dame aux Nonnains et Eglise Saint Jacques (in French), Sherbrooke College, archived from the original on 2015-12-22, retrieved 2015-12-18

- Jubainville, Henry Arbois de; Pigeotte, Léon (1866), Histoire des ducs et des comtes de Champagne ...: Fin du catalogue des actes des comtes de Champagne, tables, etc. 1866, A. Durand, retrieved 2015-12-18

- Kane, Tina (2010), The Troyes Memoire: The Making of a Medieval Tapestry, Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 978-1-84383-570-7, retrieved 2015-12-16

- Schweitzer, Jacques, "Abbaye Royale de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains", Troyes d'hier à aujourd'hui... (in French), retrieved 2015-12-18

Further reading

- Lalore, Charles (1874), Documents sur l'abbaye de Notre-Dame-aux-Nonnains, de Troyes, Dufour-Bouquot