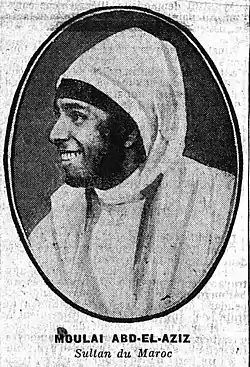

Abdelaziz of Morocco

Moulay Abd al-Aziz bin Hassan (Arabic: عبد العزيز بن الحسن), born on 24 February 1881 in Marrakesh and died on 10 June 1943 in Tangier,[1][2] was a sultan of Morocco from 9 June 1894 to 21 August 1908, as a ruler of the 'Alawi dynasty. He was proclaimed sultan at the age of sixteen after the death of his father Hassan I. Moulay Abdelaziz tried to strengthen the central government by implementing a new tax on agriculture and livestock, a measure which was strongly opposed by sections of the society. This in turn led Abdelaziz to mortgage the customs revenues and to borrow heavily from the French, which was met with widespread revolt and a revolution that deposed him in 1908 in favor of his brother Abd al-Hafid.[3] [4]

| Abd al-Aziz bin Hassan عبد العزيز بن الحسن | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sultan of Morocco | |

| Reign | 1894–1908 |

| Predecessor | Mawlay Hassan I |

| Successor | Mawlay Abd al-Hafid |

| Regent | Ahmed bin Musa (1894–1900) |

| Born | 24 February 1881 Marrakesh, Morocco |

| Died | 10 June 1943 (aged 65) Tangier, Morocco |

| Burial | |

| Wives | Lalla Khadija bint Omar al-Youssi Lalla Yasmin al-Alaoui |

| Issue | Moulay Hassan Lalla Fatima Zahra |

| House | 'Alawi dynasty |

| Father | Hassan bin Mohammed |

| Mother | Lalla Ruqiya al-Amrani |

| Religion | Maliki Sunni Islam |

Reign

Early reign

Shortly before his death in 1894[5] Hassan I designed Mawlay Adb al-Aziz his heir, despite his young age, because his mother, Lalla Ruqiya al-Amrani[6][7] was his favorite wife. His mother is often confused to be Aisha,[8] the favorite slave concubine[5][9] of Georgian origins who was bought in Istanbul by the vizir Sidi Gharnat and brought to the Sultan’s harem circa 1876.[10] By the action of Ahmed bin Musa, the Chamberlain and Grand Wazir of the former sultan Hassan I, Abd al-Aziz's accession to the sultanate was ensured with little fighting. Ba Ahmed became regent and for six years showed himself a capable ruler.[11]

In 1895, tribes of southern Morocco rose up in rebellion. At the head of an army, Abd al-Aziz marched south and defeated the southern rebels, triumphantly entering Marrakesh in March 1896 with his regent Ahmed, capturing a large booty of horses and camels.[12]

On his death in 1900 the regency ended, and Abdelaziz took the reins of government into his own hands and chose an Arab from the south, Mehdi al-Menebhi, as his chief adviser.[1] On the same year, the French administration of Algeria called for the annexation of the Tuat region, which was part of Morocco back then,[13] and owned religious and tributary allegiance to the sultans of Morocco.[14] The territory was annexed by France in 1901.[15] Subsequently, in 1903, France began to expand westwards towards Bechar and Tindouf, defeating the Moroccan forces in the Battle of Taghit and Battle of El-Moungar.[16]

As urged by his mother,[17][18] the sultan sought advice and counsel from Europe and endeavored to act on it, but advice not motivated by a conflict of interest was difficult to obtain, and in spite of the unquestionable desire of the young ruler to do what was best for the country, wild extravagance both in action and expenditure resulted, leaving the sultan with a depleted exchequer and the confidence of his people impaired. His intimacy with foreigners and his imitation of their ways were sufficient to rouse strong popular opposition.[11]

While privately owned printing presses had been allowed since 1872, Abdelaziz passed a dhahīr in 1897 that regulated what could be printed, allowing the qadi of Fes to establish a board to censor publications, and requiring that the judges be notified of any publication, so as to "avoid printing something that is not permitted."[19] According to Abdallah Laroui, these restrictions limited the volume and variety of Moroccan publications at the turn of the century, and institutions such as al-Qarawiyyin University and Sufi zawiyas became dependent on imported texts from Egypt.[19]

.jpg.webp)

His attempt to reorganize the country's finances by the systematic levy of taxes was hailed with delight, but the government was not strong enough to carry the measures through, and the money which should have been used to pay the taxes was employed to purchase firearms instead. And so the benign intentions of Moulay Abdelaziz were interpreted as weakness, and Europeans were accused of having spoiled the sultan and of being desirous of spoiling the country.[11]

When British engineers were employed to survey the route for a railway between Meknes and Fes, this was reported as indicating the sale of the country outright. The strong opposition of the people was aroused, and a revolt broke out near the Algerian frontier. Such was the state of things when the news of the Anglo-French Agreement of 1904 came as a blow to Abdelaziz, who had relied on England for support and protection against the inroads of France.[11]

Algeciras Conference

On the advice of Germany, Abdelaziz proposed an international conference at Algeciras in 1906 as a result of the First Moroccan Crisis in 1905, to consult upon methods of reform, the sultan's desire being to ensure a state of affairs which would leave foreigners with no excuse to interfere in the control of the country and thereby promote its welfare, which he had earnestly desired from his accession to power. This was not, however, the result achieved (see main article), and while on June 18 the sultan nonetheless ratified the resulting Act of the conference, which the country's delegates had found themselves unable to sign, the anarchic state into which Morocco fell during the latter half of 1906 and the beginning of 1907 revealed the young ruler as lacking sufficient strength to command the respect of his turbulent subjects.[11]

The final Act of the Conference, signed on 7 April 1906, covered the organisation of Moroccan police and customs, regulations concerning the repression of the smuggling of armaments and concessions to the European bankers from a new State Bank of Morocco, issuing banknotes backed by gold, with a 40-year term. The new state bank was to act as Morocco's Central Bank, with a strict cap on the spending of the Sherifian Empire, and administrators appointed by the national banks, which guaranteed the loans: the German Empire, United Kingdom, France and Spain. Spanish coinage continued to circulate.[20] The right of Europeans to own land was established, whilst taxes were to be levied towards public works.[21]

Rebellion of Bu Himara

Jilali bin Idris al-Yusufi al-Zarhuni (Bu Hmara) appeared in north-east Morocco in 1902 claiming to be Abd al-Aziz's older brother and the rightful heir to the throne. He had spent time in Fes and learned the politics of the Makhzen. The pretender to the throne established a rival makhzen in a remote region between Melilla and Oujda, traded with Europe and collected customs duties, imported arms, granted Europeans mining rights to Iron and Lead in the Rif, and claimed to be the mahdi.[22] He easily defeated poorly-organised armies sent by Abdelaziz to defeat him, and even threatened the capital, Fes, which proved the Minister of War al-Manabhi an incompetent general. The rebellion lasted until Abdelaziz's successor Abd al-Hafid defeated and executed Bu Hmara in 1909.[22]

Rebellion of Ahmed al-Raysuni

Ahmed al-Raysuni, a warlord and leader of the Jibala tribal confederacy, started a rebellion against the sultan of Morocco, which gave other rebels the signal to defy the Makhzen. al-Raysuni built an independent power-center and invaded Tangier in 1903. Raysuni would kidnap Christians, including Greek American Ion Perdicaris, British journalist Walter Burton Harris, and Scottish military instructor Harry Maclean, and ransom them—in open defiance of the Makhzen of Abdelaziz.[23] The Perdicaris Incident in 1904 was one of the most important of these incidents, leading to the involvement of the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain. Raysuni demanded a ransom of $70,000 and six districts from the sultan, in which the sultan eventually complied with. Raysuni supported Abd al-Hafid in taking over the Moroccan throne in the Hafidiya coup in 1908, and continued the rebellion against the later Spanish colonisers, until he was captured and imprisoned in Tamassint by Abd al-Karim in 1925, where died a few months later on the same year.[23]

Occupation of Oujda

On 19 March 1907, Émile Mauchamp, a French doctor, was assassinated by a mob in Marrakesh who stabbed him. The French press represented the murder as an "unprovoked and random act of barbarous cruelty. Shortly after Mauchamp's death, France took his death as a pretext to occupy Oujda from French Algeria, a Moroccan city on the border with French Algeria, on March 29 supposedly in retribution for the murder.[24][25]

Bombardment of Casablanca

In July 1907, tensions rose even higher, when eight Europeans were murdered by tribesmen of the Chaouia—demanding removal of the French officers from the customs house, an immediate halt on the construction of the port, and the destruction of the railroad crossing over the Sidi Belyout cemetery—and incited a riot in Casablanca, calling for Jihad.[26] European railroad workers were killed, leading to Casablanca's bombardment by France, in which parts of the city were destroyed, and 1,500 to 7,000 civilians were killed.[26] The French then sent an expeditionary force of 2,000 soldiers to the city, occupying it, and then moved into the plains surrounding the city while fighting the Chaouia in a pacification campaign.[27]

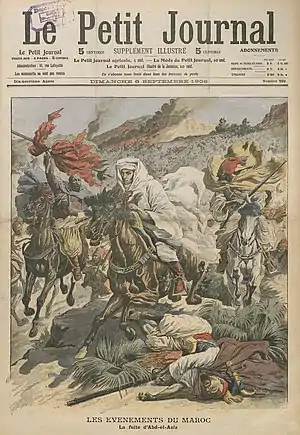

Hafidiya

A few months earlier in May 1907, the southern aristocrats, led by the head of the Glawa tribe Si al-Madani al-Glawi, invited Abd al-Hafid, an elder brother of Abd al-Aziz, and viceroy of Marrakesh, to become sultan, and the following August Abd al-Hafid was proclaimed sovereign there with all the usual formalities.[11] In September 1907, Abd al-Hafid gained the Bay'ah from Marrakesh, and in January 1908, the Ulama of Fes issued a "conditional" Bay'ah in support of Abd al-Hafid. The Bay'ah demanded that Abd al-Hafid abolishes gate taxes, liberates the French-occupied cities of Oujda and Casablanca, and confines Europeans to port cities.[28] Soon after, Abd al-Aziz arrived at Rabat from Fes and endeavored to secure the support of the European powers against his brother.[11] After months of inactivity Abd al-Aziz made an effort to restore his authority, and quitting Rabat in July he marched on Marrakesh. His force, largely owing to treachery, was completely overthrown on August 19 when nearing that city, and was defeated in the Battle of Marrakesh.[1] Abd al-Aziz fled to Settat, within the French lines around Casablanca, where he announced his abdication two days later.[29]

End of rule

In November he came to terms with his brother, and thereafter took up his residence in Tangier as a pensioner of the new sultan.[11] However the exercise of Moroccan law and order continued to deteriorate under Abd al-Hafid, leading to the Treaty of Fes in 1912, in which European nations assumed many responsibilities for the sultanate, which was divided into three zones of influence, under the French protectorate and the Spanish protectorate, while Abd al-Hafid was succeeded by his brother Yusef.[11]

Mariages and children

Moulay Abdelaziz wedded two women,[30] the first was Lalla Khadija bint Omar al-Yousi[31] commonly known as Lalla Khaduj.[31] And his second wife was a cousin of his, Lalla Yasmin al-Alaoui.[32] He had two known children:

- Moulay Hassan (b. July 1899 - d. 1919)[33] he was born in Marrakesh and died in Tangier aged 19 or 20 years old, his mother was Lalla Khadija.[33] He was half-brother of Lalla Fatima Zahra.[33]

- Lalla Fatima Zahra (b. 13 June 1927[34] - d. 15 September 2003)[35] she was born in Tangier and died in Rabat aged 76 years old,[34] her mother was Lalla Yasmin.[32] In Tangier she was educated at l'école italienne[36] then pursued high school in the same city at the collège français.[36] Aged 16 she was engaged to her future husband,[36] a distant cousin, Moulay Hassan ben el-Mehdi then Caliph of Tetuan.[36] Their wedding took place on June 6, 1949 in Tetuan.[37][38] In 1956, after Mohammed V's return from exile, her husband renewed his allegiance to the King and relinquished his position as Caliph. He was then appointed ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1965, then to Rome from 1965 to 1967. She accompanied her husband during his two mandates as ambassador. In 1969, Lalla Fatima Zahra was appointed President of the National Union of Moroccan Women[39] which she presided until her death in 2003.[39]

Later life and death

In the course of 1919, Hubert Lyautey came to the conclusion that the return of Abdelaziz from his exile in France to Morocco would be desirable as it would remove his appeal as a potential rallying point for rebellion, and subsequently let him come to live in Tangier, by then a city under unsettled status that was part neither of the Spanish nor of the French protectorates.[40] Abdelaziz led an active social but mostly nonpolitical life in the city, from 1925 the Tangier International Zone, where he spent much of his time playing golf and lived in various residences including the Villa Al Amana[41]: 315 and the Zaharat El-Jebel Palace.[42] During the Spanish annexation of Tangier in 1940, he acquiesced insofar as the Moroccan palace authorities called the "makhzen" played a significant role therein.

Abdelaziz died in Tangier in 1943 and his body was transported to Fes, where he was buried in the royal necropolis of the Moulay Abdallah Mosque.[43]

Legacy

Historian Douglas Porch characterized Abdelaziz as curious and kind in his personal relations, but a spoiled and "weak man" who failed to successfully manage foreign influences at the court. During his reign he enabled reformers who sought to modernize the kingdom, and personally displayed a high interest in European inventions, but also failed to perform the traditional religious and ceremonial functions as expected of a ruler and thus lost the faith of his own people. [44]

He was portrayed by Marc Zuber in the film The Wind and the Lion (1975), a fictional version of the Perdicaris affair.

Honours

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (civil division), 2 July 1901[45]

United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (civil division), 2 July 1901[45].svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Prussia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 22 January 1902[46]

Kingdom of Prussia: Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 22 January 1902[46]

References

- "Abd al-Aziz". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 14. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- There is a dispute on the exact date of birth with two dates given: Feb 24, 1878 or Feb 18, 1881, while Chisholm (1911) states 1880.

- "Abd al-Aziz | sultan of Morocco | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- Sasson, Albert (2007). Les couturiers du sultan: itinéraire d'une famille juive marocaine : récit (in French). Marsam Editions. p. 62. ISBN 978-9954-21-082-6.

- "Fight Expected At Fez" (PDF). The New York Times: 1. January 2, 1903.

- Ganān, Jamāl (1975). Les relations franco-allemandes et les affaires marocaines de 1901 à 1911 (in French). SNED. p. 14.

- Lahnite, Abraham (2011). La politique berbère du protectorat français au Maroc, 1912-1956: Les conditions d'établissement du Traité de Fez (in French). Harmattan. p. 44. ISBN 978-2-296-54980-7.

- Bonsal, Stephen (1893). Morocco as it is: With an Account of Sir Charles Euan Smith's Recent Mission to Fez. Harper. p. 65.

- Weisgerber, F. (2004). Au seuil du Maroc moderne (in French). Editions La Porte. p. 49. ISBN 978-9981-889-48-4.

- Bonsal, Stephen (1893). Morocco as it is: With an Account of Sir Charles Euan Smith's Recent Mission to Fez. Harper. p. 59.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abd-el-Aziz IV". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 32.

- Miller 2013, p. 56.

- Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Boundary in the Guir-Zousfana River Basin, in: African Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1970), pp. 37–56, Publ. Boston University African Studies Center: « The Algerian-Moroccan conflict can be said to have begun in 1890s when the administration and military in Algeria called for annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt, a sizable expanse of Saharan oases that was nominally a part of the Moroccan Empire (...) The Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt oases had been an appendage of the Moroccan Empire, jutting southeast for about 750 kilometers into the Saharan desert »

- Windrow, Martin (2011-12-20). French Foreign Legion 1872–1914. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-237-5.

- Claude Lefébure, Ayt Khebbach, impasse sud-est. L'involution d'une tribu marocaine exclue du Sahara, in: Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, N°41–42, 1986. Désert et montagne au Maghreb. pp. 136–157: « les Divisions d'Oran et d'Alger du 19e Corps d'armée n'ont pu conquérir le Touat et le Gourara qu'au prix de durs combats menés contre les semi-nomades d'obédience marocaine qui, depuis plus d'un siècle, imposaient leur protection aux oasiens »

- Mahuault, Jean-Paul (2005). L'épopée marocaine de la Légion étrangère, 1903-1934, ou, Trente années au Maroc (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7475-8057-1.

- FIGHT EXPECTED AT FEZ.; Rebels Only Four Hours from Capital at Last Report. LONDON TIMES -- NEW YORK TIMES Special Cablegram. January 2, 1903

- American Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events, Volume 19; Volume 34, D. Appleton, 1895, p.501

- "يومية "المساء" تروي قصة دخول المطبعة إلى المغرب". هوية بريس (in Arabic). 2014-05-04. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- ""شروط الخزيرات" .. حقيقة أشهر مؤتمر قرر في مصير المغرب". Hespress (in Arabic). Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "Algeciras Conference". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Miller 2013, p. 65.

- Miller 2013, p. 66-67.

- Yabiladi.com. "29 mars 1907 : Quand la France occupait Oujda en réponse à l'assassinat d'Émile Mauchamp". www.yabiladi.com (in French). Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Miller 2013, p. 75.

- Adam, André (1963). Histoire de Casablanca: des origines à 1914. Aix En Provence: Annales de la Faculté des Lettres Aix En Provence, Editions Ophrys. p. 62.

- Miller 2013, p. 75-76.

- Miller 2013, p. 77.

- Miller 2013, p. 78.

- "Morocco (Alaoui Dynasty)". 2005-08-29. Archived from the original on 2005-08-29. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- Rosen, Lawrence (2016). Two Arabs, a Berber, and a Jew: Entangled Lives in Morocco. University of Chicago Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-226-31748-9.

- "Yasmin Alawi". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- "Hassan Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- "Fatima Zohra Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- MATIN, LE. "En présence de S.M. le Roi Mohammed VI : Obsèques de S.A. la Princesse Lalla Fatima Zohra". Le Matin (in French). Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- Sasson, Albert (2007). Les couturiers du sultan: itinéraire d'une famille juive marocaine : récit (in French). Marsam Editions. p. 62. ISBN 978-9954-21-082-6.

- Limited, Alamy. "La Princesa Lal-la Fatima en su camino a su boda en el califa de Marruecos español en Tetuán, junio de 6. 10 de junio de 1949. (Foto de la prensa asociada Fotografía de stock - Alamy". www.alamy.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- Boda del Jalifa en Tetuán 1949 - Parte 1, retrieved 2022-10-21

- UNFM. "Historique". www.unfm.ma (in French). Archived from the original on 2015-02-28. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- José Antonio González Alcantud (2019), "Segmentariedad política y sultanato. Los sultanes marroquíes Abdelaziz, Hafid y Yussef (1894-1927) y la política colonial francesa", Estudios de Asia y África, 54:2

- Silvia Nélida Bossio, ed. (2011), Aproximación a los edificios históricos y patrimoniales de Málaga, Tetuán, Nador, Tánger y Alhucemas / Un Rapprochement entre les édifices historiques et patrimoniaux de Malaga, Tétouan, Nador, Tanger et Al Hoceima (PDF), Servicio de Programas del Ayuntamiento de Málaga

- "Le sultan Ben Arafa s'est retiré à Tanger après avoir chargé l'un de ses cousins de s'occuper des affaires du trône". Le Monde. 3 October 1955.

- Bressolette, Henri (2016). A la découverte de Fès. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2343090221.

- Porch, Douglas (June 22, 2005). The Conquest of Morocco: A History (2nd ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 55–63. ISBN 0374128804.

- "No. 27329". The London Gazette. 2 July 1901. p. 4399.

- "Rother Adler-orden", Königlich Preussische Ordensliste (supp.) (in German), vol. 1, Berlin: Gedruckt in der Reichsdruckerei, 1895, p. 7 – via hathitrust.org

Bibliography

- Miller, Susan Gilson (2013). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521810708.

- Tharaud, Jerome et Jean. Marrakech ou les Seigneurs de l'Atlas.

- Benumaya, Gil. El Jalifa en Tanger. Madrid.

External links

Media related to Abdelaziz of Morocco at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abdelaziz of Morocco at Wikimedia Commons- Morocco Alaoui dynasty

- History of Morocco

- El Protectorado español en Marruecos: la historia trascendida