Acorn

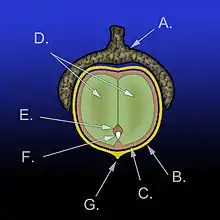

The acorn, or oaknut, is the nut of the oaks and their close relatives (genera Quercus and Lithocarpus, in the family Fagaceae). It usually contains one seed (occasionally two seeds), enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and borne in a cup-shaped cupule. Oaknuts are 1–6 cm (1⁄2–2+1⁄2 in) long and 0.8–4 cm (3⁄8–1+5⁄8 in) on the fat side. Oaknuts take between 5 and 24 months (depending on the species) to mature; see the list of Quercus species for details of oak classification, in which oaknut morphology and phenology are important factors.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,619 kJ (387 kcal) |

40.75 g | |

23.85 g | |

| Saturated | 3.102 g |

| Monounsaturated | 15.109 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 4.596 g |

6.15 g | |

| Tryptophan | 0.074 g |

| Threonine | 0.236 g |

| Isoleucine | 0.285 g |

| Leucine | 0.489 g |

| Lysine | 0.384 g |

| Methionine | 0.103 g |

| Cystine | 0.109 g |

| Phenylalanine | 0.269 g |

| Tyrosine | 0.187 g |

| Valine | 0.345 g |

| Arginine | 0.473 g |

| Histidine | 0.170 g |

| Alanine | 0.350 g |

| Aspartic acid | 0.635 g |

| Glutamic acid | 0.986 g |

| Glycine | 0.285 g |

| Proline | 0.246 g |

| Serine | 0.261 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 2 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 10% 0.112 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 10% 0.118 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 12% 1.827 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 14% 0.715 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 41% 0.528 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 22% 87 μg |

| Vitamin C | 0% 0.0 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 4% 41 mg |

| Copper | 31% .621 mg |

| Iron | 6% 0.79 mg |

| Magnesium | 17% 62 mg |

| Manganese | 64% 1.337 mg |

| Phosphorus | 11% 79 mg |

| Potassium | 11% 539 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 0 mg |

| Zinc | 5% 0.51 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 27.9 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Etymology

The word acorn (earlier akerne, and acharn) is related to the Gothic name akran, which had the sense of "fruit of the unenclosed land".[1] The word was applied to the most important forest produce, that of the oak. Chaucer spoke of "achornes of okes" in the 14th century. By degrees, popular etymology connected the word both with "corn" and "oak-horn", and the spelling changed accordingly.[2] The current spelling (emerged 15c.-16c.), derives from association with ac (Old English: "oak") + corn.[3]

Ecological role

Oaknuts play an important role in forest ecology when oaks are plentiful or dominant in the landscape.[4] The volume of the oaknut crop may vary widely, creating great abundance or great stress on the many animals dependent on oaknuts and the predators of those animals.[5] Oaknuts, along with other nuts, are termed mast.

Wildlife that consume oaknuts as an important part of their diets include birds, such as jays, pigeons, some ducks, and several species of woodpeckers. Small mammals that feed on oaknuts include mice, squirrels and several other rodents. Oaknuts have a large influence on small rodents in their habitats, as large oaknut yields help rodent populations to grow.[6]

Large mammals such as pigs, bears, and deer also consume large amounts of oaknuts; they may constitute up to 25% of the diet of deer in the autumn.[10] In Spain, Portugal and the New Forest region of southern England, pigs are still turned loose in dehesas (large oak groves) in the autumn, to fill and fatten themselves on oaknuts. Heavy consumption of oaknuts can, on the other hand, be toxic to other animals that cannot detoxify their tannins, such as horses and cattle.[11][12]

The larvae of some moths and weevils also live in young oaknuts, consuming the kernels as they develop.[13]

Oaknuts are attractive to animals because they are large and thus efficiently consumed or cached. Oaknuts are also rich in nutrients. Percentages vary from species to species, but all oaknuts contain large amounts of protein, carbohydrates and fats, as well as the minerals calcium, phosphorus and potassium, and the vitamin niacin. Total food energy in an oaknut also varies by species, but all compare well with other wild foods and with other nuts.[14]

Oaknuts also contain bitter tannins, the amount varying with the species. Since tannins, which are plant polyphenols, interfere with an animal's ability to metabolize protein, creatures must adapt in different ways to use the nutritional value oaknuts contain. Animals may preferentially select oaknuts that contain fewer tannins. When the tannins are metabolized in cattle, the tannic acid produced can cause ulceration and kidney failure.[12]

Animals that cache oaknuts, such as jays and squirrels, may wait to consume some of these oaknuts until sufficient groundwater has percolated through them to leach out the tannins. Other animals buffer their oaknut diet with other foods. Many insects, birds, and mammals metabolize tannins with fewer ill effects than do humans.

Species of oaknut that contain large amounts of tannins are very bitter, astringent, and potentially irritating if eaten raw. This is particularly true of the oaknuts of American red oaks and English oaks. The oaknuts of white oaks, being much lower in tannins, are nutty in flavor; this characteristic is enhanced if the oaknuts are given a light roast before grinding.

Tannins can be removed by soaking chopped oaknuts in several changes of water, until the water no longer turns brown. Cold water leaching can take several days, but three to four changes of boiling water can leach the tannins in under an hour.[15] Hot water leaching (boiling) cooks the starch of the oaknut, which would otherwise act like gluten in flour, helping it bind to itself. For this reason, if the oaknuts will be used to make flour, then cold water leaching is preferred.[16]

Being rich in fat, oaknut flour can spoil or molder easily and must be carefully stored. Oaknuts are also sometimes prepared as a massage oil.

Oaknuts of the white oak group, Leucobalanus, typically start rooting as soon as they are in contact with the soil (in the fall), then send up the leaf shoot in the spring.

Dispersal agents

Oaknuts are too heavy for wind dispersal, so they require other ways to spread. Oaks therefore depend on biological seed dispersal agents to move the oaknuts beyond the mother tree and into a suitable area for germination (including access to adequate water, sunlight and soil nutrients), ideally a minimum of 20–30 m (70–100 ft) from the parent tree.

Many animals eat unripe oaknuts on the tree or ripe oaknuts from the ground, with no reproductive benefit to the oak, but some animals, such as squirrels and jays serve as seed dispersal agents. Jays and squirrels that scatter-hoard oaknuts in caches for future use effectively plant oaknuts in a variety of locations in which it is possible for them to germinate and thrive.

Even though jays and squirrels retain remarkably large mental maps of cache locations and return to consume them, the odd oaknut may be lost, or a jay or squirrel may die before consuming all of its stores. A small number of oaknuts manage to germinate and survive, producing the next generation of oaks.

Scatter-hoarding behavior depends on jays and squirrels associating with plants that provide good packets of food that are nutritionally valuable, but not too big for the dispersal agent to handle. The beak sizes of jays determine how large oaknuts may get before jays ignore them.

Oaknuts germinate on different schedules, depending on their place in the oak family. Once oaknuts sprout, they are less nutritious, as the seed tissue converts to the indigestible lignins that form the root.[17]

Uses

In some cultures, oaknuts once constituted a dietary staple, though they have largely been replaced by grains and are now typically considered a relatively unimportant food, except in some Native American and Korean communities.

Several cultures have devised traditional oaknut-leaching methods, sometimes involving specialized tools, that were traditionally passed on to their children by word of mouth.[18][19]

Culinary use

Oaknuts served an important role in early human history and were a source of food for many cultures around the world.[20] For instance, the Ancient Greek lower classes and the Japanese (during the Jōmon period)[21] would eat oaknuts, especially in times of famine. In ancient Iberia they were a staple food, according to Strabo. Despite this history, oaknuts rarely form a large part of modern diets and are not currently cultivated on scales approaching that of many other nuts. However, if properly prepared (by selecting high-quality specimens and leaching out the bitter tannins in water), oaknut meal can be used in some recipes calling for grain flours. In antiquity, Pliny the Elder noted that oaknut flour could be used to make bread.[22] Varieties of oak differ in the amount of tannin in their oaknuts. Varieties preferred by Native Americans such as Quercus kelloggii (California black oak) may be easier to prepare or more palatable.[23]

In Korea, an edible jelly named dotorimuk is made from oaknuts, and dotori guksu are Korean noodles made from oaknut flour or starch. In the 17th century, a juice extracted from oaknuts was administered to habitual drunkards to cure them of their condition or else to give them the strength to resist another bout of drinking.

Oaknuts have frequently been used as a coffee substitute, particularly when coffee was unavailable or rationed. The Confederates in the American Civil War and Germans during World War II (when it was called Ersatz coffee), which were cut off from coffee supplies by Union and Allied blockades respectively, are particularly notable past instances of this use of oaknuts.

Use by Native Americans

.jpg.webp)

Oaknuts are a traditional food of many indigenous peoples of North America, and long served an especially important role for Californian Native Americans, where the ranges of several species of oaks overlap, increasing the reliability of the resource.[24] One ecology researcher of Yurok and Karuk heritage reports that "his traditional oaknut preparation is a simple soup, cooked with hot stones directly in a basket," and says he enjoys oaknuts eaten with "grilled salmon, huckleberries or seaweed."[25] Unlike many other plant foods, oaknuts do not need to be eaten or processed right away, but may be stored for a long time, much as squirrels do. In years that oaks produced many oaknuts, Native Americans sometimes collected enough oaknuts to store for two years as insurance against poor oaknut production years.

After drying in the sun to discourage mould and germination, oaknuts could be cached in hollow trees or structures on poles to keep them safe from mice and squirrels. Stored oaknuts could then be used when needed, particularly during the winter when other resources were scarce. Oaknuts that germinated in the fall were shelled and pulverized before those germinating in spring. Because of their high fat content, stored oaknuts can become rancid. Moulds may also grow on them.

The lighting of ground fires killed the larvae of oaknut moths and oaknut weevils by burning them during their dormancy period in the soil. The pests can infest and consume more than 95% of an oak's oaknuts.

Fires also released the nutrients bound in dead leaves and other plant debris into the soil, thus fertilizing oak trees while clearing the ground to make oaknut collection easier. Most North American oaks tolerate light fires, especially when consistent burning has eliminated woody fuel accumulation around their trunks. Consistent burning encouraged oak growth at the expense of other trees less tolerant of fire, thus keeping oaks dominant in the landscapes.

Oaks produce more oaknuts when they are not too close to other oaks and thus competing with them for sunlight, water and soil nutrients. The fires tended to eliminate the more vulnerable young oaks and leave old oaks which created open oak savannas with trees ideally spaced to maximize oaknut production.

Art

A motif in Roman architecture, also popular in Celtic and Scandinavian art, the oaknut symbol is used as an ornament on cutlery, furniture, and jewelry; it also appears on finials at Westminster Abbey.

In the Artemis Fowl book series, "The Ritual" describes the method used by faeries to regenerate their magical powers.[26]

Military symbolism

The oaknut was used frequently by both Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. [27] Modern US Army Cavalry Scout campaign hats still retain traces of the oaknut today.

Contemporary use as symbol

The oaknut is the symbol for the National Trails of England and Wales, and is used for the waymarks on these paths.[28] The oaknut, specifically that of the white oak, is also present in the symbol for the University of Connecticut.[29]

Oaknuts are also used as charges in heraldry.

Oaknut waymark for National Trails

Oaknut waymark for National Trails Oaknut in the coat of arms of the du Quesne family

Oaknut in the coat of arms of the du Quesne family Oak branch with two oaknuts in the coat of arms of Tammela

Oak branch with two oaknuts in the coat of arms of Tammela

See also

External links

References

- Harper, Douglas. "acorn". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Acorn". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 152–153. This cites the New English Dictionary, now the Oxford English Dictionary

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". etymonline.com. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Plumb, Timothy R., ed. (1980). Proceedings of the symposium on the ecology, management, and utilization of California oaks, June 26–28 (PDF). USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PSW-044. pp. 1 to 368. ASIN B000PMY1P8.

- King, Richie S. (2 December 2011). "After Lean Acorn Crop in Northeast, Even People May Feel the Effects". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

there is nothing unusual about large fluctuations in the annual number of acorns.

- "Acorn Study | Research | Upland Hardwood Ecology and Management | SRS". srs.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- "Acorns fatally poison 50 ponies in English forest". Horsetalk.co.nz. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "Acorn Poisoning – Are Acorns Poisonous To Horses?". Horse-advice.com. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "Acorns, Oaks and Horses: Tannin Poisoning". The Way of Horses. 15 September 2002. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Barrett, Reginald H. (1980). "Mammals of California Oak Habitats-Management Implications" (PDF). In Plumb, Timothy R. (ed.). Proceedings of the symposium on the ecology, management, and utilization of California oaks, June 26–28. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PSW-044. pp. 276–291.

- "A bumper crop of acorns causes concern for those with horses". Countryfile.com. Immediate Media Company. 19 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Barringer, Sam. "Acorns Can be Deadly". West Virginia University Extension Service. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Brown, Leland R. (1979) Insects Feeding on California Oak Treesin Proceedings of the Symposium on Multiple-Use Management of California's Hardwood Resources, Timothy Plum and Norman Pillsbury (eds.).

- "Nutrition Facts for Acorn Flour". Nutritiondata.com. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Tull, Delena (1987). A practical guide to edible & useful plants : including recipes, harmful plants, natural dyes & textile fibers. Austin, Tex.: Texas Monthly Press. ISBN 9780877190226. OCLC 15015652.

- "Two Ways to Make Cold Leached Acorn Flour – Learn How with this Guide". The Spruce. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- Janzen, Daniel H. (1971), Richard F. Johnson, Peter W. Frank and Charles Michner (ed.), "Seed Predation by Animals", Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, vol. 2, pp. 465–492, doi:10.1146/annurev.es.02.110171.002341, JSTOR 2096937

- "Indigenous Food and Traditional Recipes". NativeTech. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "Cooking With Acorns". Siouxme.com. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Bainbridge, D. A. (12–14 November 1986), Use of acorns for food in California: past, present and future, San Luis Obispo, CA.: Symposium on Multiple-use Management of California's Hardwoods, archived from the original on 27 October 2010, retrieved 1 September 2010

- Junko Habu; Habu Junko (29 July 2004). Ancient Jomon of Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77670-7.

- Alphonso, Christina (5 November 2015). "Acres of Acorns". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Derby, Jeanine A. (1980). "Acorns-Food for Modern Man" (PDF). In Plumb, Timothy R. (ed.). Proceedings of the symposium on the ecology, management, and utilization of California oaks, June 26–28. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PSW-044. pp. 360–361.

- Suttles, Wayne (1964), "(Review of) Ecological Determinants of Aboriginal California Populations, by Martin A. Baumhoff", American Anthropologist, vol. 66, no. 3, p. 676, doi:10.1525/aa.1964.66.3.02a00360

- Prichep, Deena (2 November 2014). "Nutritious Acorns Don't Have To Just Be Snacks For Squirrels". The Salt : NPR. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Colfer, Eoin (2001). Artemis Fowl. London: Viking. p. 277. ISBN 9780670899623.

- Forest Service, U.S. (27 October 2022). "Chikamauga and Chattanooga". Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- "National Trail Acorn". National Trails. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- "University of Connecticut". Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.