Foreskin

In male human anatomy, the foreskin, also known as the prepuce (/ˈpriːpjuːs/), is the double-layered fold of skin, mucosal and muscular tissue at the distal end of the human penis that covers the glans and the urinary meatus.[2] The foreskin is attached to the glans by an elastic band of tissue, known as the frenulum.[3] The outer skin of the foreskin meets with the inner preputial mucosa at the area of the mucocutaneous junction.[4] The foreskin is mobile, fairly stretchable and sustains the glans in a moist environment.[5] Except for humans, a similar structure known as a penile sheath appears in the male sexual organs of all primates and the vast majority of mammals.[6]

| Foreskin | |

|---|---|

Human foreskin fully covering the glans penis | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle, urogenital folds |

| System | Male reproductive system |

| Artery | Dorsal artery of the penis |

| Vein | Dorsal veins of the penis |

| Nerve | Dorsal nerve of the penis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | praeputium, preputium penis[1] |

| MeSH | D052816 |

| TA98 | A09.4.01.011 |

| TA2 | 3675 |

| FMA | 19639 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

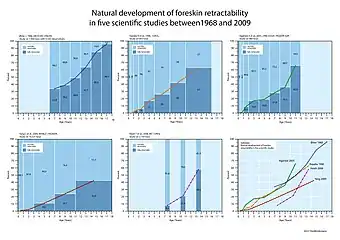

In humans, foreskin length varies widely and coverage of the glans in a flaccid and erect state can also vary.[7] The foreskin is fused to the glans at birth and is generally not retractable in infancy and early childhood.[8] Inability to retract the foreskin in childhood should not be considered a problem unless there are other symptoms.[9] Retraction of the foreskin is not recommended until it loosens from the glans before or during puberty.[9] In adults, it is typically retractable over the glans, given normal development.[9] The male prepuce is anatomically homologous to the clitoral hood in females.[10][11] In some cases, the foreskin may become subject to a pathological condition.[lower-alpha 1][12]

Structure

External

The outside of the foreskin is a continuation of the shaft skin of the penis and is covered by a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The inner foreskin is a continuation of the epithelium that covers the glans and is made up of glabrous squamous mucous membrane, like the inside of the eyelid or the mouth.[13] The mucosal aspect of the prepuce has a great capacity for self-repair.[14] The area of the outer foreskin measures 7–100 cm2,[15] and the inner foreskin measures 18–68 cm.2[7] The mucocutaneous zone occurs where the outer and inner foreskin meet. The foreskin is free to move after it separates from the glans, which usually occurs before or during puberty. The inner foreskin is attached to the glans by the frenulum, a highly vascularized tissue of the penis.[16] The World Health Organization states that "the frenulum forms the interface between the outer and inner foreskin layers, and when the penis is not erect, it tightens to narrow the foreskin opening.[16]

Subcutaneous

The human foreskin is a laminar structure made up of outer skin, mucosal epithelium, lamina propia, dartos fascia and dermis.[14][17] The superficial dartos fascia, formerly called the peripenic muscle, is one of the two sheaths of smooth muscle tissue found below the penile skin, along with the underlying Buck's fascia or deep fascia of the penis.[18] The dartos fascia extents within the skin of the prepuce and contains an abuncance of elastic fibers.[19] These fibers form a whorl at the tip of the foreskin, known as the preputial orifice, which is narrow during infancy and childhood.[20][17] The dartos fascia is sensitive to temperature and reacts to temperature changes by expanding and contracting.[21] The fascia is only loosely connected with the underlying tissue, so that it provides the mobility and elasticity of the penile skin.[19] Langerhans cells are immature dendritic cells that are found in all areas of the penile epithelium, but are most superficial in the inner surface of the foreskin.[22]

As a continuation of the human shaft skin, the prepuce receives somatosensory innervation from the bilateral dorsal nerve of the penis and branches of the perineal nerve, and autonomic innervation from the pelvic plexus.[23][24] The somatosensory receptors that are found in the prepuce are both nociceptors and mechanoreceptors, with a predominace of Meissner's corpuscles.[23][25] Blood supply to the prepuce is provided by the preputial artery, a division of the axial and dorsal artery of the penis.[18] The axial and dorsal arteries that run within the penile skin unite through perforating branches and give off the preputial arteries before they reach the corona of the glans.[26][27] The preputial vein, an extension of the superficial dorsal vein, receives blood from the prepuce and connects to the larger dorsal veins of the penis that drain the rest of the penile shaft.[28][29]

Development

Gestation

The penis develops from a primordial phallic structure that forms in the embryo during the early weeks of pregnancy, known as the genital tubercle.[30] Initially undifferentiated, the tubercle develops into a penis depending on the exposure to male hormones secreted by the testes.[31] The differentiation of the external sexual organs will be evident between twelve and sixteen weeks of gestation.[32][33] Preputial development is initiated at around eleven weeks or earlier and continues up to eighteen weeks.[34][35][36]

Historically, the theories regarding the stages of preputial development during gestation fall into two main ideas.[37] The earliest report by Schweigger-Seidel (1866)[38] and later Hunter (1935)[39] suggested the formation of the prepuce out of dorsal skin and its progressive distal extension to completelly cover and eventually fuse with the epithelium of the glans.[37] Glenister (1956)[40] expanded the theory suggesting that the preputial fold results as an ingrowth of the cellular lamina, which rolls outwards over the glans, but with the resultant preputial lamina also expanding backwards to form an ingrowing fold at the coronal sulcus.[37] The same idea was also described by Cold & Taylor (1999),[17] Johnson (1920)[41] and others.

By eleven and twelve weeks of gestation, the process of preputial formation is evident as a thickening of the epidermis that separates from the penis creating a raised fold, known as the preputial fold.[42] On the underside of this structure forms the preputial lamina, which expands dorsolaterally over the base of the developing glans.[43][44] At thirteen weeks, the prepuce has not yet extended to the distal tip of the glans covering only a part of its surface.[45] By sixteen weeks, the bilateral preputial folds cover most of the glans and the ventral sides of the prepuce fuse in the midline.[46] The penile raphe, the continuation of the perineal raphe in human males, occurs on the ventral side of the penis as a manifestation of the fusion of the urethral and preputial folds.[47] The dorsal nerve of the penis, which is present as early as nine weeks of gestation, completely expands through branches to the distal end of the glans and prepuce by sixteen weeks.[48] At nineteen weeks, foreskin development is complete.[35] Towards the end of the second trimester,[49] the glans and the prepuce have completely fused together by the preputial, sometimes referred to as balanopreputial lamina.[50] At birth, this shared membrane is physiologically adherent to the glans preventing retraction in infancy and early childhood.[51][52] The phenomenon of non-retractile foreskin in children naturally starts to resolve in varying ages; in childhood, preadolescence or puberty.[53]

Retraction

During the first years of life, the inner foreskin is fused to the glans making them hard to manually separate.[8][54] At that time, forced retraction can cause pain or microtearing and is thus not recommended.[55][56][57] The two surfaces may begin to separate from early childhood, but complete separation and retraction is a process that normally occurs over time.[58][59] The phenomenon of non retractile or tight foreskin in childhood, sometimes referred to as physiologic phimosis,[52] may completely resolve before, during or even after puberty.[9][60][56] When the foreskin starts to become retractile, a pediatrician can recommend careful retraction at home and rinsing with water during bath.[55] Mild soap may be used, but can be avoided, if it causes irritation.[57] If full retraction is hard to achieve, the child may only wash the exposed area of the glans.[61] Since there is no specific age when non-retractile foreskin begins to resolve, the time of foreskin retraction can vary considerably among children.[53]

During puberty, as the male begins to sexually mature, foreskin retractability gradually increases allowing more comfortable exposure of the glans when needed. Gentle washing under the foreskin during shower and maintaining good genital hygiene is sufficient to prevent smegma buildup.[62][58] Smegma is an oily secretion in the genitals of both sexes that maintains the moist texture of the mucosal surfaces and prevents friction.[63][64] In boys, it helps resolve the natural adhension of the glans and inner prepuce.[65][54] By the end of puberty, most boys have a fully retractable foreskin.[60]

Variability

In children, the foreskin usually covers the glans completely but in adults it may not. During erection, the degree of automatic foreskin retraction varies considerably; in some adults, when the foreskin is longer than the erect penis, it will not spontaneously retract upon erection. In this case, the foreskin remains covering all or some of the glans until retracted manually or by sexual activity. The foreskin can be classified as long, when the preputial orifice extents beyond the glans, medium, when the preputial orifice is located around the meatus, and short, when most of the glans is exposed.[66] The variation of long foreskin was regarded by Chengzu (2011) as 'prepuce redundant'. Frequent retraction and washing under the foreskin is suggested for all adults, particularly for those with a long or 'redundant' foreskin.[67] Some males, according to Xianze (2012), may be reluctant for their glans to be exposed because of discomfort when it chafes against clothing, although the discomfort on the glans was reported to diminish within one week of continuous exposure.[68] Guochang (2010) states that for those whose foreskins are too tight to retract or have some adhesions, forcible retraction should be avoided since it may cause injury.[69]

Function

The World Health Organization (WHO) stated in 2007 that there was "debate about the role of the foreskin, with possible functions including keeping the glans moist, protecting the developing penis in utero, or enhancing sexual pleasure due to the presence of nerve receptors".[16] The foreskin helps to provide sufficient skin during an erection. The foreskin protects the glans.[71] In infants, it protects the glans from ammonia and feces in diapers, which reduces the incidence of meatal stenosis. And the foreskin helps prevent the glans from getting abrasions and trauma throughout life.

The foreskin contains Meissner's corpuscles, which are one of a group of nerve endings involved in fine-touch sensitivity. Compared to other hairless skin areas on the body, the Meissner's index was highest in the finger tip (0.96) and lowest in the foreskin (0.28) which suggested that the foreskin has the least sensitive hairless tissue of the body.[72]

Research into the sexual function of the foreskin has generally been of poor quality and the results are inconclusive and a source of controversy.[73] Anti-circumcision activists claim that the foreskin is functionally significant for sexual pleasure, but such claims are not supported by good evidence.[74] In 2009, the World Health Organization called it a "myth" that circumcision has any adverse effect on sexual pleasure. The view is echoed by other major medical organizations.[75]

Evolution

The foreskin is present in the vast majority of mammals, including non-human primates, such as the chimpanzee.[16] In primates, the foreskin is present in the genitalia of both sexes and likely has been present for millions of years of evolution.[76] The evolution of complex penile morphologies like the foreskin may have been influenced by females.[77][78][79]

In modern times, there is controversy regarding whether the foreskin is a vital or vestigial structure.[80] In 1949, British physician Douglas Gairdner noted that the foreskin plays an important protective role in newborns. He wrote, "It is often stated that the prepuce is a vestigial structure devoid of function... However, it seems to be no accident that during the years when the child is incontinent the glans is completely clothed by the prepuce, for, deprived of this protection, the glans becomes susceptible to injury from contact with sodden clothes or napkin."[80] During the physical act of sex, the foreskin reduces friction, which can reduce the need for additional sources of lubrication.[80] The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia has written that the foreskin is "composed of an outer skin and an inner mucosa that is rich in specialized sensory nerve endings and erogenous tissue."[71] In the March 2017 publication of the Global Health Journal: Science and Practice, Morris and Krieger wrote, "The variability in foreskin size is consistent with the foreskin being a vestigial structure."[81]

Clinical significance

The foreskin can be involved in balanitis, phimosis, sexually transmitted infection and penile cancer.[82] The American Academy of Pediatricians' now expired 2012 technical report on circumcision found that the foreskin can harbor micro-organisms that may increase the risk of urinary tract infections in some infants and contribute to the transmission of some sexually transmitted infections in adults.[83] In some cases of recurrent pathologies, excessive soap washing may irritate the mucosa, therefore washing of the area should be done gently.[84]

Frenulum breve is a frenulum that is insufficiently long to allow the foreskin to fully retract, which may lead to discomfort during intercourse.

Phimosis is a condition where the foreskin of an adult cannot be retracted properly. Phimosis can be treated by using topical steroid ointments and using lubricants during sex; for severe cases circumcision may be necessary.[85] Posthitis is an inflammation of the foreskin.

A condition called paraphimosis may occur if a tight foreskin becomes trapped behind the glans and swells as a restrictive ring. This can cut off the blood supply, resulting in ischemia of the glans penis.[85]

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that most commonly occurs in adult women, although it may also be seen in men and children. Topical clobetasol propionate and mometasone furoate were proven effective in treating genital lichen sclerosus.[86]

Some birth defects of the foreskin can occur; all of them are rare. In aposthia there is no foreskin at birth,[87]: 37–39 in micropathia the foreskin does not cover the glans,[87]: 41–45 and in macroposthia, also called and congenital megaprepuce, the foreskin extends well past the end of the glans.[87]: 47–50

It has been found that larger foreskins place men who are not circumcised at an increased risk of HIV infection[88] most likely due to the larger surface area of inner foreskin and the high concentration of Langerhans cells.[89]

Society and culture

Modifications

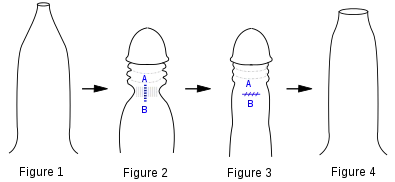

Fig 1. Penis with tight phimotic ring making it difficult to retract the foreskin.

Fig 2. Foreskin retracted under anaesthetic with the phimotic ring or stenosis constricting the shaft of the penis and creating a "waist".

Fig 3. Incision closed laterally.

Fig 4. Penis with the loosened foreskin replaced over the glans.

Circumcision is the removal of the foreskin, either partially or completely. It is most commonly performed as an elective procedure for prophylactic, cultural, or religious reasons.[90][91]: 257 Circumcision may also be performed on children or adults to treat phimosis, balanitis, and other pathologies.[92] The ethics of circumcision in children is a source of controversy.[93][94] Some men have used weights to stretch the skin of the penis to regrow a foreskin; the resulting tissue does cover the glans but does not replicate the features of a foreskin.[95] Other cultural or aesethetic practices include genital piercings involving the foreskin and slitting the foreskin.[96] Preputioplasty is the most common foreskin reconstruction technique, most often done when a boy is born with a foreskin that is too small;[97]: 177 a similar procedure is performed to relieve a tight foreskin without resorting to circumcision.[97]: 181

Foreskin-based products

Foreskins obtained from circumcision procedures are frequently used by biochemical and micro-anatomical researchers to study the structure and proteins of human skin. In particular, foreskins obtained from newborns have been found to be useful in the manufacturing of more human skin.[98]

Foreskins of babies are also used for skin graft tissue,[99][100][101] and for β-interferon-based drugs.[102]

Foreskin-derived fibroblasts have been used in biomedical research,[103] and cosmetic applications.[104]

History

The foreskin was considered a sign of beauty, civility, and masculinity throughout the Greco-Roman world.[105] In ancient Greece, foreskins were valued, especially those that were longer.[106] The earliest known illustrative depiction of the foreskin dates back to Egyptian kingdoms.[107]

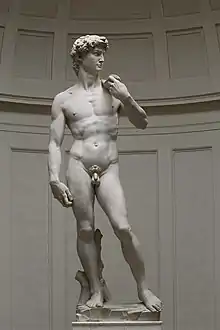

The foreskin has also been depicted in art from different historical ages:

David Marble sculpture, 1504 AD

David Marble sculpture, 1504 AD "Orestes at Delphi". Painting of two naked males, ca. 330 BC.

"Orestes at Delphi". Painting of two naked males, ca. 330 BC. The Marathon Youth, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, ca. 340–330 BC

The Marathon Youth, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, ca. 340–330 BC

References

- Paulsen, Friedrich; Waschke, Jens (2023). Sobotta Atlas of Anatomy, Vol. 2, 17th Ed., English/Latin: Internal Organs. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2971. ISBN 978-0-70206-770-9. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- Kirby R, Carson C, Kirby M (2009). Men's Health (3rd ed.). New York: Informa Healthcare. p. 283. ISBN 978-1-4398-0807-8. OCLC 314774041.

- Male circumcision : global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety, and acceptability. Helen Weiss, World Health Organization, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. ISBN 978-92-4-159616-9. OCLC 425961131.

The foreskin is attached to the glans by the frenulum

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Raynor, Stephen C. (2010-01-01), Holcomb, George Whitfield; Murphy, J. Patrick; Ostlie, Daniel J. (eds.), "chapter 61 - CIRCUMCISION", Ashcraft's Pediatric Surgery (Fifth Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 791–795, ISBN 978-1-4160-6127-4, retrieved 2022-10-24,

The prepuce is a specialized junctional mucocutaneous tissue that provides adequate skin and mucosa

- Collier, Roger (2011-11-22). "Vital or vestigial? The foreskin has its fans and foes". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 183 (17): 1963–1964. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4014. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 3225416. PMID 22025652.

It is also a warm, moist environment that may allow viral particles to linger longer on the penis

- Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (2015), Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (ed.), "Prepuce", Rare Congenital Genitourinary Anomalies: An Illustrated Reference Guide, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 33–41, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-43680-6_3, ISBN 978-3-662-43680-6, retrieved 2022-12-01

- Werker PM, Terng AS, Kon M (September 1998). "The prepuce free flap: dissection feasibility study and clinical application of a super-thin new flap". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 102 (4): 1075–1082. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809040-00024. PMID 9734426. S2CID 37976399.

- Dave, Sumit; Afshar, Kourosh; Braga, Luis H.; Anderson, Peter (2018). "CUA guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (2): E76–E99. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5033. ISSN 1920-1214. PMC 5937400. PMID 29381458.

At birth, the inner foreskin is usually fused to the glans penis and should not be forcibly retracted

- Potts, Jeannette (2004). "Penis Problems". Essential Urology: A Guide to Clinical Practice. Humana Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781592597376.

Virtually all foreskins become retractable in puberty. Thus, phimosis is not a pathological condition in young children unless it is associated with balanitis, or, rarely, urinary retention.

- Crooks, Robert L.; Baur, Karla (2010-01-01). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-81294-4.

- Sloane, Ethel (2002). Biology of Women. Delmar Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-7668-1142-3.

- Shah M (January 2008). The Male Genitalia: A Clinician's Guide to Skin Problems and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-84619-040-7. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- Cunha, Gerald R.; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Baskin, Laurence S. (2020). "Development of the human prepuce and its innervation". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 111: 22–40. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2019.10.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6936222. PMID 31654825.

ts outer surface is continuous with skin of the penile shaft and is covered by a glabrous stratified squamous keratinized epithelium. Its inner mucosal surface is lined by variably-keratinized squamous epithelium

- Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (2020), Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (ed.), "Histology of the Prepuce", Normal and Abnormal Prepuce, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 59–65, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37621-5_6, ISBN 978-3-030-37621-5, S2CID 216401902, retrieved 2022-12-01

- Kigozi G, Wawer M, Ssettuba A, Kagaayi J, Nalugoda F, Watya S, et al. (October 2009). "Foreskin surface area and HIV acquisition in Rakai, Uganda (size matters)". AIDS. 23 (16): 2209–2213. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330eda8. PMC 3125976. PMID 19770623.

- "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Cold, C.J.; Taylor, J.R. (2002-05-27). "The prepuce". BJU International. 83 (S1): 34–44. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. ISSN 1464-4096. PMID 10349413. S2CID 30559310.

- Hsieh, Cheng‐Hsing; Hsu, Geng‐Long; Chang, Shang‐Jen; Yang, Stephen Shei‐Dei; Liu, Shih‐Ping; Hsieh, Ju‐Ton (2020). "Surgical niche for the treatment of erectile dysfunction". International Journal of Urology. 27 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1111/iju.14157. ISSN 0919-8172. PMID 31812157. S2CID 208870116.

- Hadidi, Ahmed (2022). Hypospadias Surgery: An Illustrated Textbook. Springer. pp. 115, 624. ISBN 9783030942489.

- McGregor, Thomas B.; Pike, John G.; Leonard, Michael P. (2007). "Pathologic and physiologic phimosis". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (3): 445–448. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 1949079. PMID 17872680.

physiologic phimosis consists of a pliant, unscarred preputial orifice

- Gibson, Alan; Akinrinsola, Adetokunbo; Patel, Tejesh; Ray, Arijit; Tucker, John; McFadzean, Ian (August 2002). "Pharmacology and thermosensitivity of the dartos muscle isolated from rat scrotum". British Journal of Pharmacology. 136 (8): 1194–1200. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704830. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 1573456. PMID 12163353.

- McCoombe SG, Short RV (July 2006). "Potential HIV-1 target cells in the human penis". AIDS. 20 (11): 1491–1495. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000237364.11123.98. PMID 16847403. S2CID 22839409.

- Raynor, Stephen C. (2010-01-01), Holcomb, George Whitfield; Murphy, J. Patrick; Ostlie, Daniel J. (eds.), "chapter 61 - CIRCUMCISION", Ashcraft's Pediatric Surgery (Fifth Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 791–795, ISBN 978-1-4160-6127-4, retrieved 2022-10-24

- Cunha, Gerald R.; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Baskin, Laurence S. (2020). "Development of the human prepuce and its innervation". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 111: 22–40. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2019.10.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6936222. PMID 31654825.

branches of the dorsal nerve of the penis are already present within the preputial mesenchyme", "Parasympathetic and sympathetic input to the penis is via the pelvic plexus

- García‐Mesa, Yolanda; García‐Piqueras, Jorge; Cobo, Ramón; Martín‐Cruces, José; Suazo, Iván; García‐Suárez, Olivia; Feito, Jorge; Vega, José A. (2021). "Sensory innervation of the human male prepuce: Meissner's corpuscles predominate". Journal of Anatomy. 239 (4): 892–902. doi:10.1111/joa.13481. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 8450466. PMID 34120333.

Certain preputial sensory corpuscles, such as Meissner's corpuscles, Pacinian corpuscles, and Merkel cell‐neurite complexes, function as mechanoreceptors in human glabrous skin

- Quartey, J. K.M. (2006), Schreiter, F.; Jordan, G.H. (eds.), "Anatomy and Blood Supply of the Urethra and Penis", Urethral Reconstructive Surgery, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 13–14, doi:10.1007/3-540-29385-x_3, ISBN 978-3-540-29385-9, retrieved 2022-10-26,

Behind the corona, the axial arteries send perforating branches through Buck's fascia to anastomose with the terminal branches of the dorsal arteries before they end in the glans. The attenuated continuation of the arteries pass into the prepuce.

- Jacob, S. (2008-01-01), Jacob, S. (ed.), "Chapter 4 - Abdomen", Human Anatomy, Churchill Livingstone, pp. 71–123, ISBN 978-0-443-10373-5, retrieved 2022-11-09

- Hinman, F. (1991). "The blood supply to preputial island flaps". The Journal of Urology. 145 (6): 1232–1235. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38584-1. ISSN 0022-5347. PMID 2033699.

- Hsieh, Cheng‐Hsing; Hsu, Geng‐Long; Chang, Shang‐Jen; Yang, Stephen Shei‐Dei; Liu, Shih‐Ping; Hsieh, Ju‐Ton (2020). "Surgical niche for the treatment of erectile dysfunction". International Journal of Urology. 27 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1111/iju.14157. ISSN 0919-8172. PMID 31812157. S2CID 208870116.

The superficial dorsal vein drains blood from the foreskin into saphenous and external pudendal veins

- W.George, D.Wilson, Fredrick, Jean (1984). "2 - Sexual Differentiation". Fetal Physiology and Medicine (Second, Revised ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 57–79. doi:10.1016/B978-0-407-00366-8.50008-3. ISBN 9780407003668.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - George, Fredrick W.; Wilson, Jean D. (1984-01-01), Beard, RICHARD W.; Nathanielsz, PETER W. (eds.), "2 - Sexual Differentiation", Fetal Physiology and Medicine (Second Edition), Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 57–79, ISBN 978-0-407-00366-8, retrieved 2022-11-04

- Merz, Eberhard (2005). Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology. F. Bahlmann (2nd ed., fully rev ed.). Stuttgart: Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-131882-4. OCLC 57251410.

- Schünke, Michael (2006). Thieme atlas of anatomy. General anatomy and musculoskeletal system. Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher, Lawrence M. Ross, Edward D. Lamperti. Stuttgart: Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-142081-7. OCLC 62906603.

- Liu, Xin; Liu, Ge; Shen, Joel; Yue, Aaron; Isaacson, Dylan; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Liaw, Aron; Cunha, Gerald R.; Baskin, Laurence (2018). "Human Glans and Preputial Development". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 103: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2018.08.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6234068. PMID 30245194.

Human preputial development begins at ~11 weeks of gestation [...] when the epithelium thickens on the dorsal aspect of the glans penis and forms the preputial placode [...] from which bilateral preputial laminar processes extend ventrally into the glanular mesenchyme

- Favorito, Luciano Alves; Balassiano, Carlos Miguel; Costa, Waldemar Silva; Sampaio, Francisco José Barcellos (2012). "Development of the human foreskin during the fetal period". Histology and Histopathology. 27 (8): 1041–1045. doi:10.14670/HH-27.1041. ISSN 1699-5848. PMID 22763876.

The complete foreskin was formed only in the fetuses at 18 and 19 WPC, in which the foreskin totally covered the glans.

- Cunha, Gerald R.; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Baskin, Laurence S. (2020). "Development of the human prepuce and its innervation". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 111: 22–40. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2019.10.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6936222. PMID 31654825.

...the earliest stages (8 weeks) of human preputial development to advanced preputial development at 17 weeks of gestation.

- Cunha, Gerald R.; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Baskin, Laurence S. (2020). "Development of the human prepuce and its innervation". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 111: 22–40. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2019.10.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6936222. PMID 31654825.

- Schweigger-Seidel, F. (1866). "Zur Entwickelung des Praeputium". Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin. 37 (2): 219–225. doi:10.1007/bf01935635. ISSN 0945-6317. S2CID 26136414.

- Hunter, Richard H. (1935). "Notes on the Development of the Prepuce". Journal of Anatomy. 70 (Pt 1): 68–75. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1249280. PMID 17104576.

- Glenister, T. W. (1956). "A consideration of the processes involved in the development of the prepuce in man". British Journal of Urology. 28 (3): 243–249. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1956.tb04763.x. ISSN 0007-1331. PMID 13364260.

- Johnson, Franklin P. (1920). "The Later Development of the Urethra in the Male". Journal of Urology. 4 (6): 447–501. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)74157-2. ISSN 0022-5347.

- Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (2020), Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (ed.), "Embryology of Prepuce", Normal and Abnormal Prepuce, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 29–33, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37621-5_4, ISBN 978-3-030-37621-5, S2CID 216479793, retrieved 2022-11-15,

The first indication of the onset of the developmental processes of the prepuce involved the appearance of a raised fold (the preputial fold), just at the coronary sulcus.

- Liu, Xin; Liu, Ge; Shen, Joel; Yue, Aaron; Isaacson, Dylan; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Liaw, Aron; Cunha, Gerald R.; Baskin, Laurence (2018). "Human Glans and Preputial Development". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 103: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2018.08.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6234068. PMID 30245194.

Development of the prepuce is initiated by ~12 weeks with the appearance of a novel structure, the preputial placode, which is a dorsal thickening of the epidermis on the dorsal aspect of the developing glans penis.

- Cunha, Gerald R.; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Baskin, Laurence S. (2020). "Development of the human prepuce and its innervation". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 111: 22–40. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2019.10.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6936222. PMID 31654825.

The process of preputial lamina formation is initiated dorsally or dorsal-laterally in the proximal aspect of the glans at 11 to 12.5 weeks

- Favorito, Luciano Alves; Balassiano, Carlos Miguel; Costa, Waldemar Silva; Sampaio, Francisco José Barcellos (2012). "Development of the human foreskin during the fetal period". Histology and Histopathology. 27 (8): 1041–1045. doi:10.14670/HH-27.1041. ISSN 1699-5848. PMID 22763876.

The glans was partially covered by the foreskin in the fetus at 13 WPC

- Liu, Xin; Liu, Ge; Shen, Joel; Yue, Aaron; Isaacson, Dylan; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Liaw, Aron; Cunha, Gerald R.; Baskin, Laurence (2018). "Human Glans and Preputial Development". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 103: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2018.08.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6234068. PMID 30245194.

From the lateral aspect of the preputial placode the bilateral preputial laminae expand ventrally until the preputial folds (foreskin) cover all of the glans, fusing in the ventral midline at ~16 weeks gestation.

- Liu, Xin; Liu, Ge; Shen, Joel; Yue, Aaron; Isaacson, Dylan; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Liaw, Aron; Cunha, Gerald R.; Baskin, Laurence (2018). "Human Glans and Preputial Development". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 103: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2018.08.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6234068. PMID 30245194.

Formation of the prepuce occurs after formation of the urethra in the penile shaft. The penile raphe within the penile shaft is a manifestation of fusion of the urethral folds within the shaft

- Cunha, Gerald R.; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Baskin, Laurence S. (2020). "Development of the human prepuce and its innervation". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 111: 22–40. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2019.10.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6936222. PMID 31654825.

Examination of the ontogeny of innervation of the glans penis and prepuce reveals the presence of the dorsal nerve of the penis as early as 9 weeks of gestation. Nerve fibers enter the glans penis proximally and extend distally...to eventually reach the distal aspect of the glans and prepuce by 14 to 16 weeks of gestation.

- Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (2020), Fahmy, Mohamed A. Baky (ed.), "Embryology of Prepuce", Normal and Abnormal Prepuce, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 29–33, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37621-5_4, ISBN 978-3-030-37621-5, S2CID 216479793, retrieved 2022-11-15,

Prepuce completely covering and fusing with the glans structure at around twenty-fourth week of gestation.

- Carmack, Adrienne; Milos, Marilyn Fayre (2017). "Catheterization without foreskin retraction". Canadian Family Physician. 63 (3): 218–220. ISSN 0008-350X. PMC 5349724. PMID 28292801.

The foreskin and glans are connected by the balanopreputial lamina, a membrane similar to the synechial membrane that connects the nail bed and the fingernail... This membrane and the small preputial opening prevent retraction in boys with normal physiologic phimosis.

- Liu, Xin; Liu, Ge; Shen, Joel; Yue, Aaron; Isaacson, Dylan; Sinclair, Adrian; Cao, Mei; Liaw, Aron; Cunha, Gerald R.; Baskin, Laurence (2018). "Human Glans and Preputial Development". Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 103: 86–99. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2018.08.002. ISSN 0301-4681. PMC 6234068. PMID 30245194.

At birth the solid preputial lamina is intact and thus "physiologically adherent" to the glans. Thereafter, the preputial lamina will canalize creating the preputial space that "houses" the glans.

- "Newborn male circumcision | Canadian Paediatric Society". cps.ca. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

In the male newborn, the mucosal surfaces of the inner foreskin and glans penis adhere to one another; [...] Until this developmental process is complete, the best descriptor to use is 'nonretractile foreskin' rather than the confusing and perhaps erroneous term 'physiologic phimosis

- Dave, Sumit; Afshar, Kourosh; Braga, Luis H.; Anderson, Peter (2018). "CUA guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (2): E76–E99. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5033. ISSN 1920-1214. PMC 5937400. PMID 29381458.

the incidence of non-retractable physiological phimosis was 50% in grade 1 boys and decreased to 35% in grade 4 and 8% in grade 7 boys

- Lissienko, Katherine (2011-09-13). "How To Care For Your Child's Foreskin". KidsHealth NZ. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- "How to take care of a baby's uncircumcised penis". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- "Care for an Uncircumcised Penis". HealthyChildren.org. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Philadelphia, The Children's Hospital of (2014-08-23). "Care of the Uncircumcised Penis". www.chop.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- "Circumcision of baby boys: Information for parents". caringforkids.cps.ca. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- "Newborn male circumcision | Canadian Paediatric Society". cps.ca. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- McGregor, Thomas B.; Pike, John G.; Leonard, Michael P. (2007). "Pathologic and physiologic phimosis: Approach to the phimotic foreskin". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (3): 445–448. PMC 1949079. PMID 17872680.

most foreskins will become retractile by adulthood.

- Philadelphia, The Children's Hospital of (2014-08-23). "Care of the Uncircumcised Penis". www.chop.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

As long as the foreskin doesn't easily retract, only the outside needs to be cleaned. If the foreskin retracts a little, just clean the exposed area of the glans with water.

- Øster J (April 1968). "Further Fate of the Foreskin: Incidence of Preputial Adhesions, Phimosis, and Smegma among Danish Schoolboys". Arch Dis Child. 43 (228): 200–202. doi:10.1136/adc.43.228.200. PMC 2019851. PMID 5689532.

The production of smegma increases from the age of 12-13, but our actual figures of the incidence of smegma can only be of limited significance, as the boys received regular instruction about preputial hygiene.

- "Smegma: What It Is, Prevention & How To Get Rid Of It". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- Chung, J.; Park, Chang Soo; Lee, Sang Don (2019). "Microbiology of smegma: Prospective comparative control study". Investigative and Clinical Urology. 60 (2): 127–132. doi:10.4111/icu.2019.60.2.127. PMC 6397923. PMID 30838346. S2CID 69175186.

- Dave, Sumit; Afshar, Kourosh; Braga, Luis H.; Anderson, Peter (2018). "CUA guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (2): E76–E99. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5033. ISSN 1920-1214. PMC 5937400. PMID 29381458.

The collection of smegma (a white exudate of skin cells and keratin) separating the prepuce from the glans and repeated reflex erections are the primary mechanisms that lead to resolution of physiological adhesions over time.

- Velazquez, Elsa F.; Bock, Adelaida; Soskin, Ana; Codas, Ricardo; Arbo, Manuel; Cubilla, Antonio L. (2003). "Preputial variability and preferential association of long phimotic foreskins with penile cancer: an anatomic comparative study of types of foreskin in a general population and cancer patients". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 27 (7): 994–998. doi:10.1097/00000478-200307000-00015. ISSN 0147-5185. PMID 12826892. S2CID 34091663.

- Chengzu L (2011). "Health Care for Foreskin Conditions". Epidemiology of Urogenital Diseases. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- Xianze L (2012). Tips on Puberty Health. Beijing: People's Education Press.

- Guochang H (2010). General Surgery. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House.

- College of Physicians; Surgeons of British Columbia (2009). "Circumcision (Infant Male)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- Cox G, Krieger JN, Morris BJ (June 2015). "Histological Correlates of Penile Sexual Sensation: Does Circumcision Make a Difference?". Sexual Medicine. 3 (2): 76–85. doi:10.1002/sm2.67. PMC 4498824. PMID 26185672.

- Paraboschi I, Garriboli M (2020). "Chapter 7: Functions of the Prepuce". In Baky Fahmy, MA (ed.). Normal and Abnormal Prepuce. Springer. pp. 67–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37621-5_7. ISBN 978-3-030-37620-8.

- Schoen EJ (2007). "Chapter 9: Male circumcision". In Kandeel FR (ed.). Male Sexual Dysfunction – Pathophysiology and Treatment. Taylor & Francis. p. 102. ISBN 9781420015089.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision "Technical Report" (2012) addresses sexual function, sensitivity and satisfaction without qualification by age of circumcision. Sadeghi-Nejad et al. "Sexually transmitted diseases and sexual function" (2010) addresses adult circumcision and sexual function. Doyle et al. "The Impact of Male Circumcision on HIV Transmission" (2010) addresses adult circumcision and sexual function. Perera et al. "Safety and efficacy of nontherapeutic male circumcision: a systematic review" (2010) addresses adult circumcision and sexual function and satisfaction.

- Dave S, Afshar K, Braga LH, Anderson P (February 2018). "Canadian Urological Association guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants (full version)". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (2): E76–E99. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5033. PMC 5937400. PMID 29381458.

There is lack of any convincing evidence that neonatal circumcision will impact sexual function or cause a perceptible change in penile sensation in adulthood.

- Shabanzadeh DM, Düring S, Frimodt-Møller C (July 2016). "Male circumcision does not result in inferior perceived male sexual function - a systematic review". Danish Medical Journal (Systematic review). 63 (7). PMID 27399981.

- Friedman B, Khoury J, Petersiel N, Yahalomi T, Paul M, Neuberger A (September 2016). "Pros and cons of circumcision: an evidence-based overview". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 22 (9): 768–774. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.030. PMID 27497811.

- Staff. "Statement on Newborn Male Circumcision". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

Some parents also may worry that circumcision harms a man's sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction. However, current evidence shows that it does not.

- Shezi, Mirriam Hlelisani; Tlou, Boikhutso; Naidoo, Saloshni (February 16, 2023). "Knowledge, attitudes and acceptance of voluntary medical male circumcision among males attending high school in Shiselweni region, Eswatini: a cross sectional study". BMC Public Health. 23 (1): 349. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15228-3. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 9933013. PMID 36797696.

It was interesting to note that the young males in this study had misconceptions about sexual pleasure post male circumcision...

- Todd Sorokan, S; Finlay, Jane; Jefferies, Ann (September 8, 2015). "2015 Policy Statement on Newborn Male Circumcision". Canadian Paediatric Society. 20 (6): 311–320. doi:10.1093/pch/20.6.311. PMC 4578472. PMID 26435672.

...medical studies do not support circumcision as having a negative impact on sexual function or satisfaction in males or their partners.

- World Health Organization; UNAIDS; Jhpiego (December 2009). "Manual for Male Circumcision Under Local Anaesthesia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2012.

...there are many myths about male circumcision that circulate. For example, some people think that circumcision can cause impotence (failure of erection) or reduce sexual pleasure. Others think that circumcision will cure impotence. Let me assure you that none of these is true.

Alt URL Archived 30 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Dave S, Afshar K, Braga LH, Anderson P (February 2018). "Canadian Urological Association guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants (full version)". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (2): E76–E99. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5033. PMC 5937400. PMID 29381458.

- Martin RD (1990). Primate Origins and Evolution: A Phylogenetic Reconstruction. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08565-4.

- Diamond JM (1997). Why Sex is Fun: The Evolution of Human Sexuality. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-465-03126-9.

- Darwin C (1871). The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: Murray. ISBN 978-1-148-75093-4.

- Short RV (1981). "Sexual selection in man and the great apes". In Graham CE (ed.). Reproductive Biology of the Great Apes: Comparative and Biomedical Perspectives. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 9780323149716. Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

- Collier R (November 2011). "Vital or vestigial? The foreskin has its fans and foes". CMAJ. 183 (17): 1963–1964. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4014. PMC 3225416. PMID 22025652.

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN, Klausner JD (March 2017). "CDC's Male Circumcision Recommendations Represent a Key Public Health Measure". Global Health, Science and Practice. 5 (1): 15–27. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00390. PMC 5478224. PMID 28351877.

- Simmons MN, Jones JS (May 2007). "Male genital morphology and function: an evolutionary perspective". The Journal of Urology. 177 (5): 1625–1631. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.011. PMID 17437774.

- Blank, Susan; Brady, Michael; Buerk, Ellen; Carlo, Waldemar; Diekema, Douglas; Freedman, Andrew; Maxwell, Lynne; Wegner, Steven (September 2012). "Male circumcision". Pediatrics. 130 (3): e756–e785. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1990. PMID 22926175. The technical report was published in conjunction with an updated statement of policy on circumcision: Blank, Susan; Brady, Michael; Buerk, Ellen; Carlo, Waldemar; Diekema, Douglas; Freedman, Andrew; Maxwell, Lynne; Wegner, Steven (September 2012). "Circumcision policy statement" (PDF). Pediatrics. 130 (3): 585–586. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1989. PMID 22926180. S2CID 207166111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2017-10-04.

- Birley, H. D.; Walker, M. M.; Luzzi, G. A.; Bell, R.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Byrne, M.; Renton, A. M. (1993). "Clinical features and management of recurrent balanitis; association with atopy and genital washing". Genitourinary Medicine. 69 (5): 400–403. doi:10.1136/sti.69.5.400. ISSN 0266-4348. PMC 1195128. PMID 8244363.

- "Phimosis (tight foreskin)". NHS Choices. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Chi CC, Kirtschig G, Baldo M, Brackenbury F, Lewis F, Wojnarowska F (December 2011). "Topical interventions for genital lichen sclerosus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (12): CD008240. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008240.pub2. PMC 7025763. PMID 22161424.

- Fahmy M (2017). Congenital Anomalies of the Penis – Springer. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-43310-3.

- Van Howe RS, Sorrells MS, Snyder JL, Reiss MD, Milos MF (December 2016). "Letter from Van Howe et al Re: Examining Penile Sensitivity in Neonatally Circumcised and Intact Men Using Quantitative Sensory Testing: J. A. Bossio, C. F. Pukall and S. S. Steele J Urol 2016;195:1848-1853". The Journal of Urology. 196 (6): 1824. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.127. PMID 28181790.

- Szabo R, Short RV (June 2000). "How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?". BMJ. 320 (7249): 1592–1594. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592. PMC 1127372. PMID 10845974.

- Alan Glasper, Edward; Richardson, James; Randall, Duncan (2021). "Promote, Restore, and Stabilise Health Status in Children". A Textbook of Children's and Young People's Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 382. ISBN 9780702065033.

- Cox G, Morris BJ (2012). "Chapter 21: Why Circumcision:From Prehistory to the Twenty-First Century". In Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 243–259. ISBN 978-1-4471-2858-8.

- McClung C, Voelzke B (2012). "Chapter 14: Adult Circumcision". In Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 165–175. ISBN 978-1-4471-2858-8.

- "Policy Statement On Circumcision". Royal Australasian College of Physicians. September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

The Paediatrics and Child Health Division, The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) has prepared this statement on routine circumcision of infants and boys to assist parents who are considering having this procedure undertaken on their male children and for doctors who are asked to advise on or undertake it. After extensive review of the literature the RACP reaffirms that there is no medical indication for routine neonatal circumcision. Circumcision of males has been undertaken for religious and cultural reasons for many thousands of years. It remains an important ritual in some religious and cultural groups.…In recent years there has been evidence of possible health benefits from routine male circumcision. The most important conditions where some benefit may result from circumcision are urinary tract infections, HIV and later cancer of the penis.…The complication rate of neonatal circumcision is reported to be around 1% and includes tenderness, bleeding and unhappy results to the appearance of the penis. Serious complications such as bleeding, septicaemia and may occasionally cause death (1 in 550,000). The possibility that routine circumcision may contravene human rights has been raised because circumcision is performed on a minor and is without proven medical benefit. Whether these legal concerns are valid will be known only if the matter is determined in a court of law. If the operation is to be performed, the medical attendant should ensure this is done by a competent operator, using appropriate anaesthesia and in a safe child-friendly environment. In all cases where parents request a circumcision for their child the medical attendant is obliged to provide accurate information on the risks and benefits of the procedure. Up-to-date, unbiased written material summarizing the evidence should be widely available to parents. Review of the literature in relation to risks and benefits shows there is no evidence of benefit outweighing harm for circumcision as a routine procedure in the neonate.

- Medical Ethics Committee (June 2006). "The law and ethics of male circumcision - guidance for doctors". British Medical Association. Archived from the original on 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- Collier R (December 2011). "Whole again: the practice of foreskin restoration". CMAJ. 183 (18): 2092–2093. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4009. PMC 3255154. PMID 22083672.

- "Paraphimosis : Article by Jong M Choe, MD, FACS". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- Snodgrass WT (2012). "Chapter 15: Foreskin Reconstruction". In Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 177–181. ISBN 978-1-4471-2858-8.

- McKie R (1999-04-04). "Foreskins for Skin Grafts". The Toronto Star.

- "High-Tech Skinny on Skin Grafts". 1999-02-16. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Grand DJ (August 15, 2011). "Skin Grafting". Medscape. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- Amst C, Carey J (July 27, 1998). "Biotech Bodies". www.businessweek.com. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Cowan AL (April 19, 1992). "Wall Street; A Swiss Firm Makes Babies Its Bet". New York Times:Business. Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Hovatta O, Mikkola M, Gertow K, Strömberg AM, Inzunza J, Hreinsson J, et al. (July 2003). "A culture system using human foreskin fibroblasts as feeder cells allows production of human embryonic stem cells". Human Reproduction. 18 (7): 1404–1409. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg290. PMID 12832363.

- Malamut M (14 April 2015). "The 'Baby Foreskin Facial' Is a Real Thing". Boston Magazine.

- Hall, Robert (August 1992). "Epispasm: Circumcision in Reverse". Bible Review. 8 (4): 52–57.

- Hodges FM (2001). "The ideal prepuce in ancient Greece and Rome: male genital aesthetics and their relation to lipodermos, circumcision, foreskin restoration, and the kynodesme". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (3): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. JSTOR 44445662. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193.

- Raveenthiran V (2020). "History of the Prepuce". Normal and Abnormal Prepuce. Springer. pp. 7–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37621-5_2. ISBN 978-3-030-37620-8. S2CID 216446879.

External links

- Infant foreskin care at Kidshealth.org.nz

- "Care for an Uncircumcised Penis". Healthy Children. American Academy of Pediatrics. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Management of foreskin conditions Archived 2014-04-06 at the Wayback Machine – Statement from the British Association of Paediatric Urologists on behalf of the British Association of Paediatric Surgeons and The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists (2007).