Actinomucor elegans

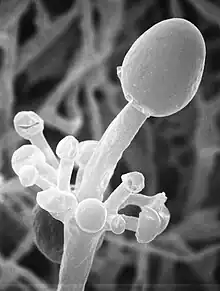

Actinomucor elegans was originally described by Schostakowitsch in Siberia in 1898 and reevaluated by Benjamin and Hesseltine in 1957.[1] Commonly found in soil[2] and used for the commercial production of tofu and other products made by soy fermentation. Its major identifying features are its spine-like projections on the sporangiophore[1] and its ribbon-like hyphal structure when found in the tissue of a host.[2]

| Actinomucor elegans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Actinomucor |

| Species: | A. elegans |

| Binomial name | |

| Actinomucor elegans (Eidam) C.R. Benj. & Hesselt. 1957 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Actinomucor elegans meitauza (Y.K. Shih) R.Y. Zheng & X.Y. Liu 2005 | |

Taxonomy

The Actinomucor genus has many shared similarities with the genus Mucor. The specific differences lie in the branched hyphae of Actinomucor that give rise to rhizoids and sporangiophores. In terms of its differences from other similar genera, the limited growth of hyphae and the variation in the structure of columella and sporangiophores give Actinomucor multiple differentiable characteristics to other genera.[1]

Morphology

Mycelial growths of A. elegans have a high number of rhizoids branching out of each individual growth. On portions of growth that lack opposite rhizoids, aseptate hyphal growths with clear sporangiophores that are found with extreme variability in length and width. These hyphal structures grow out in whorled structures with growth terminating in the development of sporangiophores.[1][2][3][4][5] The sporangia are oval to spherical in shape and 17–50 μm in diameter. The walls of the sporangia possess prominent spine-like projections, which is a major identifier of this specific fungus.[1] The coloration of colonies of this fungi is white to cream-colored with an abundance of aerial mycelium. Cultures allowed to develop for a longer period of time (greater than 48 hours) change to become yellowish to buff color with increased aerial mycelium development and tight interweaving of these mycelia.[1] When this fungus is found in a human host the structure is explained to be similar to the genus Mucor, but with unique ribbon-like hyphal structures and irregular branching and thickness.[2][4][5]

Human pathogen

Identified as an arising human fungal pathogen the recorded instances of mucormycosis due to A. elegans are limited to four cases. The invasion mechanisms found for A. elegans are through spore inhalation[3] or entry from ruptures in the skin.[5] This pathogen is highly-deadly when found in an immunocompromised individual,[4] and can develop into a serious infection for immunocompetent individuals as well.[3] Immunocompromised patients are affected worse by infection due to their immune system being unable to stop the germination of fungal spores resulting in there being no mechanism to slow the colonization once this pathogen is introduced.[4] In all cases involving immunocompromised individuals, the relatively large visible location of necrosis seemed to be the first indicator of an invasion.[1][2][3][5] It is thought that these necrotic areas are indicative of the place on the body in which inoculation occurred.[2] A. elegans as a pathogen is categorized as a mucormycosis-causing fungus, and because of this, the current leading treatment for this type of pathogen is the removal of necrotic tissue in an effort to remove the fungal elements from the body. The severity of infection from A. elegans is due to its propensity for invasion of the vascular system and hematogenous dispersion ultimately leading to necrosis of tissue. To limit the suffering, discomfort, or expiration of a patient infected with this pathogen an early suspicion of this specific fungi needs to be established. Early identification is important as it limits the time for the fungi to colonize the host before doctors can gather infected tissue to isolate and culture the fungi to confirm its presence in the patient. Because of this pathogen’s relative rarity, the time required to correctly identify the pathogen is usually not rapid enough resulting in high mortality rates of individuals infected.[5]

Fermentation of food products

Tofu

Mold fermentation in the production of tofu utilizes A. elegans. Through fermentation, A. elegans breaks down large macromolecules and converts them into simple fatty acids, amino acids, or sugars resulting in increased digestibility for humans. Ultimately increasing the functional and nutritional properties of tofu.[6]

Sufu

Another use of A. elegans is for the fermentation processing of sufu pehtze. A. elegans is specifically proficient for the production because it possesses important enzymes for the fermentation process and results in nutritional improvements of the food. Specific enzymes that add marketable aspects to this product include glutaminase which increases palatability, and α-galactosidase[7] which reduces flatulence in people consuming the product.[8]

Debittering soy protein hydrolysates

Actinomucor elegans is utilized for its debittering ability as well. Protein hydrolysates, such as whey and casein protein mixes all utilize proteolytic enzyme treatment to achieve heightened nutritional value, but paired with these nutritional improvements commonly comes a bitter taste. The bitter taste results from the amount and structure of hydrophobic amino acids formed in peptides. When paired with alcalase, A. elegans results in increased hydrolysis of amino acids in protein hydrolysates. Specifically, this hydrolysis occurs by A. elegans acting as an exopeptidase increasing the rate of hydrolysis resulting in a decrease of bitterness.[9]

Plastic degradation

To combat the white pollution caused by worldwide plastic waste many biodegradable products are now made out of polylactic acids (PLA) or polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate (PBAT). Lipases secreted by A. elegans were found to be the second most proficient at expediting the full breakdown of these compounds. When a coculture of the most proficient dissolver of these compounds Pseudomonas mendocina and the second-most proficient A. elegans it resulted in a substantially higher degradation rate than either fungus could achieve individually. In the observed physical structure of this relationship, it was found that P. mendocina was attached to the mycelia of A. elegans. This synergy resulted in a higher degradation rate because A. elegans possesses a large hyphal network resulting in larger colonization of the molecule, which increased the number of colonization sites for P. mendocina resulting in the superior degrading of the molecule. From a biochemical standpoint, the degradation occurred because the lipases of A. elegans and the proteases of P. mendocina catalyzed the ester bonds of the PLA/PBAT molecules. This finding shows that there is an efficient added degradation mechanism available to be employed if products formed out of PBAT/PLA become more widespread lowering the chances for waste buildup and decreasing the harmful effect of plastics in the environment by having the ability for its full degradation to be done quickly.[10]

References

- Khan, Zia U.; Ahmad, Suhail; Mokaddas, Eiman; Chandy, Rachel; Cano, Josep; Guarro, Josep (2008). "Actinomucor elegans var. kuwaitiensis isolated from the wound of a diabetic patient". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 94 (3): 343–352. doi:10.1007/s10482-008-9251-1. ISSN 0003-6072. PMID 18496764. S2CID 54626956. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- Mahmud, Aneela; Lee, Richard; Munfus-McCray, Delicia; Kwiatkowski, Nicole; Subramanian, Aruna; Neofytos, Dennis; Carroll, Karen; Zhang, Sean X. (16 February 2012). "Actinomucor elegans as an Emerging Cause of Mucormycosis". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 50 (3): 1092–1095. doi:10.1128/jcm.05338-11. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 3295095. PMID 22205785.

- Davel, G., Featherston, P., Fernández Anibal, Abrantes, R., Canteros, C., Rodero, L., Sztern, C., & Perrotta, D. (2001). Maxillary sinusitis caused by actinomucor elegans. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 39(2), 740–742. doi:10.1128/jcm.39.2.740-742.2001

- Dorin, J., D’Aveni, M., Debourgogne, A., Cuenin, M., Guillaso, M., Rivier, A., Gallet, P., Lecoanet, G., & Machouart, M. (2017). Update on Actinomucor elegans , a mucormycete infrequently detected in human specimens: How combined microbiological tools contribute efficiently to a more accurate medical care. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 307(8), 435–442. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.10.010

- Tully, Charla C, et al. “Fatal Actinomucor Elegans Var. Kuwaitiensis Infection Following Combat Trauma.” Journal of Clinical Microbiology, American Society for Microbiology, 1 October 2009, https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/JCM.00797-09 Archived 11 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- Yin, Liqing, et al. “Improvement of the Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Nutritional Quality of Tofu Fermented with Actinomucor Elegans.” ScienceDirect, Elsevier, 20 August 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0023643820310768 Archived 11 June 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- Huang, L., Wang, C., Zhang, Y., Chen, X., Huang, Z., Xing, G., & Dong, M. (2019). Degradation of anti‐nutritional factors and reduction of immunoreactivity of tempeh by co‐fermentation with rhizopus oligosporus rt ‐3 and actinomucor elegans dcy ‐1. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 54(5), 1836–1848. doi:10.1111/ijfs.14085

- Han, B.-Z., Ma, Y., Rombouts, F. M., & Robert Nout, M. J. (2003). Effects of temperature and relative humidity on growth and enzyme production by Actinomucor elegans and Rhizopus oligosporus during sufu Pehtze preparation. Food Chemistry, 81(1), 27–34. doi:10.1016/s0308-8146(02)00347-3

- Li, Li, et al. “Debittering Effect of Actinomucor Elegans Peptidases on Soybean Protein Hydrolysates.” Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2023 Oxford

- Jia, H., Zhang, M., Weng, Y., & Li, C. (2021). Degradation of polylactic acid/polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate by Coculture of Pseudomonas Mendocina and Actinomucor elegans. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 403, 123679. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123679