Acute coronary syndrome

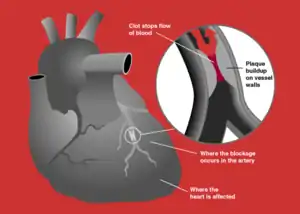

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a syndrome (a set of signs and symptoms) due to decreased blood flow in the coronary arteries such that part of the heart muscle is unable to function properly or dies.[1] The most common symptom is centrally located pressure-like chest pain, often radiating to the left shoulder[2] or angle of the jaw, and associated with nausea and sweating. Many people with acute coronary syndromes present with symptoms other than chest pain, particularly women, older people, and people with diabetes mellitus.[3]

| Acute coronary syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Blockage of a coronary artery | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

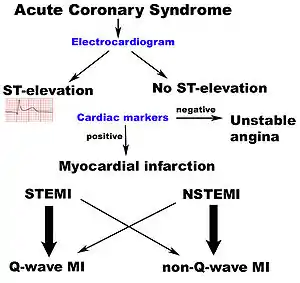

Acute coronary syndrome is subdivided in three scenarios depending primarily on the presence of electrocardiogram (ECG) changes and blood test results (a change in cardiac biomarkers such as troponin levels:[4] ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or unstable angina.[5] STEMI is characterised by complete blockage of a coronary artery resulting in necrosis of part of the heart muscle indicated by ST elevation on ECG, NSTEMI is characterised by a partially blocked coronary artery resulting in necrosis of part of the heart muscle that may be indicated by ECG changes, and unstable angina is characterised by ischemia of the heart muscle that does not result in cell injury or necrosis.[6][7]

ACS should be distinguished from stable angina, which develops during physical activity or stress and resolves at rest. In contrast with stable angina, unstable angina occurs suddenly, often at rest or with minimal exertion, or at lesser degrees of exertion than the individual's previous angina ("crescendo angina"). New-onset angina is also considered unstable angina, since it suggests a new problem in a coronary artery.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of the acute coronary syndromes are similar.[8] The cardinal symptom of critically decreased blood flow to the heart is chest pain, experienced as tightness, pressure, or burning.[9] Localisation is most commonly around or over the chest and may radiate or be located to the arm, shoulder, neck, back, upper abdomen, or jaw.[9] This may be associated with sweating, nausea, or shortness of breath.[8][9] Previously, the word "atypical" was used to describe chest pain not typically heart-related, however this word is not recommended and has been replaced by "noncardiac" to describe chest pain that indicate a low likelihood of heart-related pain.[9]

In unstable angina, symptoms may appear on rest or on minimal exertion.[6] The symptoms can last longer than those in stable angina, can be resistant to rest or medicine, and can get worse over time.[8][10]

Though ACS is usually associated with coronary thrombosis, it can also be associated with cocaine use.[11] Chest pain with features characteristic of cardiac origin (angina) can also be precipitated by profound anemia, brady- or tachycardia (excessively slow or rapid heart rate), low or high blood pressure, severe aortic valve stenosis (narrowing of the valve at the beginning of the aorta), pulmonary artery hypertension and a number of other conditions.[12]

Pathophysiology

In those who have ACS, atheroma rupture is most commonly found 60% when compared to atheroma erosion (30%), thus causes the formation of thrombus which block the coronary arteries. Plaque rupture is responsible for 60% in ST elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) while plaque erosion is responsible for 30% of the STEMI and vice versa for Non ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). In plaque rupture, the content of the plaque is lipid rich, collagen poor, with abundant inflammation which is macrophage predominant, and covered with a thin fibrous cap. Meanwhile, in plaque erosion, the plaque is rich with extracellular matrix, proteoglycan, glycoaminoglycan, but without fibrous caps, no inflammatory cells, and no large lipid core. After the coronary arteries are unblocked, there is a risk of reperfusion injury due spreading inflammatory mediators throughout the body. Investigations is still underway on the role of cyclophilin D in reducing the reperfusion injury.[13]

Other, less common, causes of acute coronary syndrome include spontaneous coronary artery dissection,[14] ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA), and myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA).[15]

Diagnosis

Electrocardiogram

In the setting of acute chest pain, the electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) is the investigation that most reliably distinguishes between various causes.[17] The ECG should be done as early as practicable, including in the ambulance if possible.[18] ECG changes indicating acute heart damage include: ST elevation, new left bundle branch block and ST depression amongst others. The absence of ECG changes does not immediately distinguish between unstable angina and NSTEMI.[6]

Blood tests

Change in levels of cardiac biomarkers, such as troponin I and troponin T, are indicative of myocardial infarction including both STEMI and NSTEMI, however their levels are not affected in unstable angina.[6]

Prediction scores

A combination of cardiac biomarkers and risk scores, such as HEART score and TIMI score, can help assess the possibility of myocardial infarction in the emergency setting.[19][13]

Prevention

Acute coronary syndrome often reflects a degree of damage to the coronaries by atherosclerosis. Primary prevention of atherosclerosis is controlling the risk factors: healthy eating, exercise, treatment for hypertension and diabetes, avoiding smoking and controlling cholesterol levels; in patients with significant risk factors, aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. Secondary prevention is discussed in myocardial infarction.[20]

After a ban on smoking in all enclosed public places was introduced in Scotland in March 2006, there was a 17% reduction in hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome. 67% of the decrease occurred in non-smokers.[21]

Treatment

People with presumed ACS are typically treated with aspirin, clopidogrel or ticagrelor, nitroglycerin, and if the chest discomfort persists morphine.[22] Other analgesics such as nitrous oxide are of unknown benefit.[22] Angiography is recommended in those who have either new ST elevation or a new left or right bundle branch block on their ECG.[1] Unless the person has low oxygen levels additional oxygen does not appear to be useful.[23]

STEMI

If the ECG confirms changes suggestive of myocardial infarction (ST elevation in specific leads, a new left bundle branch block or a true posterior MI pattern), thrombolytics may be administered or percutaneous coronary intervention may be performed. In the former, medication is injected that stimulates fibrinolysis, destroying blood clots obstructing the coronary arteries . In the latter, a flexible catheter is passed via the femoral or radial artery and advanced to the heart to identify blockages in the coronary arteries. When occlusions are found, they can be intervened upon mechanically with angioplasty and usually stent deployment if a lesion, termed the culprit lesion, is thought to be causing myocardial damage. Data suggest that rapid triage, transfer and treatment is essential.[24] The time frame for door-to-needle thrombolytic administration according to American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines should be within 30 minutes, whereas the door-to-balloon percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) time should be less than 90 minutes. It was found that thrombolysis is more likely to be delivered within the established ACC guidelines among patients with STEMI as compared to PCI according to a 2009 case control study.[25]

NSTEMI and NSTE-ACS

If the ECG does not show typical changes consistent with STEMI, the term "non-ST segment elevation ACS" (NSTE-ACS) may be used and encompasses "non-ST elevation MI" (NSTEMI) and unstable angina.

The accepted management of unstable angina and acute coronary syndrome is therefore empirical treatment with aspirin, a second platelet inhibitor such as clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor, and heparin (usually a low-molecular weight heparin), with intravenous nitroglycerin and opioids if the pain persists. The heparin-like drug known as fondaparinux appears to be better than enoxaparin.[26]

If there is no evidence of ST segment elevation on the electrocardiogram, delaying urgent angioplasty until the next morning is not inferior to doing so immediately.[27] Using statins in the first 14 days after ACS reduces the risk of further ACS.[28]

Cocaine-associated ACS should be managed in a manner similar to other patients with acute coronary syndrome except beta blockers should not be used and benzodiazepines should be administered early.[29]

Prognosis

Prediction scores

The TIMI risk score can identify high risk patients in non-ST segment elevation MI ACS[30] and has been independently validated.[31][32]

Based on a global registry of 102,341 patients, the GRACE risk score estimates in-hospital, 6 months, 1 year, and 3-year mortality risk after a heart attack.[33] It takes into account clinical (blood pressure, heart rate, EKG findings) and medical history.[33]

Biomarkers

The aim of prognostic markers is to reflect different components of pathophysiology of ACS. For example:

- Natriuretic peptide – both B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP can be applied to predict the risk of death and heart failure following ACS.

- Monocyte chemo attractive protein (MCP)-1 – has been shown in a number of studies to identify patients with a higher risk of adverse outcomes after ACS.

Coronary CT angiography combined with troponin levels is also helpful to triage those who are susceptible to ACS. F-fluoride positron emission tomography is also helpful in identifying those with high risk, lipid-rich coronary plaques.[13]

Day of admission

Studies have shown that for ACS patients, weekend admission is associated with higher mortality and lower utilization of invasive cardiac procedures, and those who did undergo these interventions had higher rates of mortality and complications than their weekday counterparts. This data leads to the possible conclusion that access to diagnostic/interventional procedures may be contingent upon the day of admission, which may impact mortality.[34][35] This phenomenon is described as weekend effect.

See also

- Allergic acute coronary syndrome (Kounis syndrome)

References

- Amsterdam, E. A.; Wenger, N. K.; Brindis, R. G.; Casey, D. E.; Ganiats, T. G.; Holmes, D. R.; Jaffe, A. S.; Jneid, H.; Kelly, R. F.; Kontos, M. C.; Levine, G. N.; Liebson, P. R.; Mukherjee, D.; Peterson, E. D.; Sabatine, M. S.; Smalling, R. W.; Zieman, S. J. (23 September 2014). "2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 130 (25): e344–e426. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. PMID 25249585.

- Goodacre S, Pett P, Arnold J, Chawla A, Hollingsworth J, Roe D, Crowder S, Mann C, Pitcher D, Brett C (November 2009). "Clinical diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome in patients with chest pain and a normal or non-diagnostic electrocardiogram". Emergency Medicine Journal. 26 (12): 866–870. doi:10.1136/emj.2008.064428. PMID 19934131. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017.

- Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ (June 2000). "Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, and Mortality among Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Presenting Without Chest Pain". JAMA. 283 (24): 3223–3229, vi. doi:10.1001/jama.283.24.3223. PMID 10866870.

- Grech ED, Ramsdale DR (June 2003). "Acute coronary syndrome: unstable angina and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction". BMJ. 326 (7401): 1259–61. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1259. PMC 1126130. PMID 12791748.

- Torres M, Moayedi S (May 2007). "Evaluation of the acutely dyspneic elderly patient". Clin. Geriatr. Med. 23 (2): 307–25, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2007.01.007. PMID 17462519.

- Collet, Jean-Philippe; Thiele, Holger; Barbato, Emanuele; Barthélémy, Olivier; Bauersachs, Johann; et al. (7 April 2021). "2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation". European Heart Journal. 42 (14): 1289–1367. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. ISSN 1522-9645. PMID 32860058.

Unstable angina is defined as myocardial ischaemia at rest or on minimal exertion in the absence of acute cardiomyocyte injury/necrosis. [...] Compared with NSTEMI patients, individuals with unstable angina do not experience acute cardiomyocyte injury/necrosis.

- Barthélémy, Olivier; Jobs, Alexander; Meliga, Emanuele; et al. (7 April 2021). "Questions and answers on workup diagnosis and risk stratification: a companion document of the 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation". European Heart Journal. 42 (14): 1379–1386. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa602. ISSN 1522-9645. PMC 8026278. PMID 32860030.

NSTEMI is characterized by ischaemic symptoms associated with acute cardiomyocyte injury (=rise and/or fall in cardiac troponin T/I), while ischaemic symptoms at rest (or minimal effort) in the absence of acute cardiomyocyte injury define unstable angina. This translates into an increased risk of death in NSTEMI patients, while unstable angina patients are at relatively low short-term risk of death.

- "Acute Coronary Syndromes (Heart Attack; Myocardial Infarction; Unstable Angina) - Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Gulati, Martha; Levy, Phillip D.; Mukherjee, Debabrata; Amsterdam, Ezra; Bhatt, Deepak L.; et al. (30 November 2021). "2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 144 (22): e368–e454. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 34709879.

- "Unstable Angina".

- Achar SA, Kundu S, Norcross WA (2005). "Diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome". Am Fam Physician. 72 (1): 119–26. PMID 16035692. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007.

- "Chest Pain in the Emergency Department: Differential Diagnosis". The Cardiology Advisor. 20 January 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Eisen, Alon; Giugliano, Robert P; Braunwald, Eugene (20 July 2016). "Updates on acute coronary syndrome: A review". JAMA Cardiology. 1 (16): 718–730. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2049. PMID 27438381.

- Franke, Kyle B; Wong, Dennis TL; Baumann, Angus; Nicholls, Stephen J; Gulati, Rajiv; Psaltis, Peter J (4 April 2019). "Current state-of-play in spontaneous coronary artery dissection". Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. 9 (3): 281–298. doi:10.21037/cdt.2019.04.03. PMC 6603494. PMID 31275818.

- Tamis-Holland, JE (27 March 2019). "Diagnosis and Management of MINOCA Patients". Circulation. 139 (18): 891–908. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000670. PMID 30913893.

- Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP (2000). "Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction". J Am Coll Cardiol. 36 (3): 959–69. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. PMID 10987628.

- Chun AA, McGee SR (2004). "Bedside diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review". Am. J. Med. 117 (5): 334–43. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.021. PMID 15336583.

- Neumar, RW; Shuster, M; Callaway, CW; Gent, LM; Atkins, DL; Bhanji, F; Brooks, SC; de Caen, AR; Donnino, MW; Ferrer, JM; Kleinman, ME; Kronick, SL; Lavonas, EJ; Link, MS; Mancini, ME; Morrison, LJ; O'Connor, RE; Samson, RA; Schexnayder, SM; Singletary, EM; Sinz, EH; Travers, AH; Wyckoff, MH; Hazinski, MF (3 November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315–67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

- Fanaroff, Alexander C.; Rymer, Jennifer A.; Goldstein, Sarah A.; Simel, David L.; Newby, L. Kristin (10 November 2015). "Does This Patient With Chest Pain Have Acute Coronary Syndrome?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review". JAMA. 314 (18): 1955–1965. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12735. ISSN 1538-3598. PMID 26547467.

- Grundy, Scott M.; Stone, Neil J.; Bailey, Alison L.; Beam, Craig; Birtcher, Kim K.; Blumenthal, Roger S.; Braun, Lynne T.; de Ferranti, Sarah; Faiella-Tommasino, Joseph; Forman, Daniel E.; Goldberg, Ronald; Heidenreich, Paul A.; Hlatky, Mark A.; Jones, Daniel W.; Lloyd-Jones, Donald (25 June 2019). "2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 73 (24): 3168–3209. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.002. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 30423391.

- Pell JP, Haw S, Cobbe S, et al. (2008). "Smoke-free Legislation and Hospitalizations for Acute Coronary Syndrome" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (5): 482–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0706740. hdl:1893/16659. PMID 18669427.

- O'Connor RE, Brady W, Brooks SC, et al. (November 2010). "Part 10: acute coronary syndromes: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S787–817. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971028. PMID 20956226.

- Neumar, RW; Shuster, M; Callaway, CW; Gent, LM; Atkins, DL; Bhanji, F; Brooks, SC; de Caen, AR; Donnino, MW; Ferrer, JM; Kleinman, ME; Kronick, SL; Lavonas, EJ; Link, MS; Mancini, ME; Morrison, LJ; O'Connor, RE; Samson, RA; Schexnayder, SM; Singletary, EM; Sinz, EH; Travers, AH; Wyckoff, MH; Hazinski, MF (3 November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315–67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

- Blankenship JC, Skelding KA (2008). "Rapid Triage, Transfer, and Treatment with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction". Acute Coronary Syndromes. 9 (2): 59–65. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.

- Janda, SP; Tan, N (2009). "Thrombolysis versus primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation myocardial infarctions at Chilliwack General Hospital". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 25 (11): e382–4. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70165-5. PMC 2776568. PMID 19898701.

- Bundhun, PK; Shaik, M; Yuan, J (8 May 2017). "Choosing between Enoxaparin and Fondaparinux for the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 17 (1): 116. doi:10.1186/s12872-017-0552-z. PMC 5422952. PMID 28482804.

- Montalescot G, Cayla G, Collet JP, Elhadad S, Beygui F, Le Breton H, et al. (2009). "Immediate vs delayed intervention for acute coronary syndromes: a randomized clinical trial". JAMA. 302 (9): 947–54. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1267. PMID 19724041.

- Vale, N; Nordmann, AJ; Schwartz, GG; de Lemos, J; Colivicchi, F; den Hartog, F; Ostadal, P; Macin, SM; Liem, AH; Mills, EJ; Bhatnagar, N; Bucher, HC; Briel, M (1 September 2014). "Statins for acute coronary syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD006870. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006870.pub3. PMID 25178118.

- McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. (April 2008). "Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology". Circulation. 117 (14): 1897–907. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188950. PMID 18347214.

- Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. (2000). "The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making". JAMA. 284 (7): 835–42. doi:10.1001/jama.284.7.835. PMID 10938172.

- Pollack CV, Sites FD, Shofer FS, Sease KL, Hollander JE (2006). "Application of the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome to an unselected emergency department chest pain population". Academic Emergency Medicine. 13 (1): 13–8. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.031. PMID 16365321.

- Chase M, Robey JL, Zogby KE, Sease KL, Shofer FS, Hollander JE (2006). "Prospective validation of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Risk Score in the emergency department chest pain population". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 48 (3): 252–9. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.032. PMID 16934646.

- Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Van de Werf F, Avezum A, Goodman SG, Flather MD, Anderson FA Jr, Granger CB (2006). "Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE)". BMJ. 333 (7578): 1091. doi:10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55. PMC 1661748. PMID 17032691.

- Khoshchehreh M, Groves EM, Tehrani D, Amin A, Patel PM, Malik S (2016). "Changes in mortality on weekend versus weekday admissions for Acute Coronary Syndrome in the United States over the past decade". Int J Cardiol. 210: 164–172. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.087. PMC 4801736. PMID 26950171.

- Kostis W.J.; Demissie K.; Marcella S.W.; Shao Y.-H.; Wilson A.C.; Moreyra A.E. (2007). "Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction". N Engl J Med. 356 (11): 1099–1109. doi:10.1056/nejmoa063355. PMID 17360988.