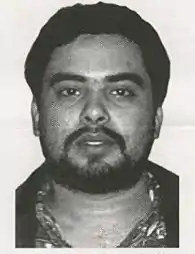

Adán Medrano Rodríguez

Adán Javier Medrano Rodríguez (24 December 1969), also known as El Licenciado (The Attorney), was a Mexican convicted drug lord and former high-ranking member of the Gulf Cartel, a criminal group based in Tamaulipas, Mexico. He joined the cartel during the 1990s, and was a trusted enforcer of former kingpin Osiel Cárdenas Guillén. His roles in the cartel were managing drug shipments from Guatemala to Mexico, supervising murders ordered by Cárdenas, and coordinating cash transfers from the U.S. to Mexico.

Adán Medrano Rodríguez | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Adán Javier Medrano Rodríguez 24 December 1969 |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Drug lord |

| Employer | Gulf Cartel |

| Height | 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) |

| Criminal status |

|

| Notes | |

Wanted by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas for drug trafficking and assault | |

In 1999, Medrano and his associates threatened two U.S. agents at gunpoint in Matamoros after the agents traveled there with an informant to gather intelligence on the cartel's operations. The agents and informant returned to the U.S. unharmed, and the incident triggered a massive manhunt for Medrano and the rest of the cartel leadership. A US$2 million bounty was offered for his capture, and he was charged with a number of crimes. Medrano was arrested in 2002, and sentenced to 44 years in prison in 2006. He was unexpectedly released from prison during the early 2010s.

Early life and career

Medrano was born on 24 December 1969. According to his Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) profile, he is 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m), weighed 140 lb (64 kg), and has brown hair and eyes. Medrano's birthplace and nationality are "unknown". The profile included his Social Security number, and described him as a Hispanic of medium build and complexion and "armed and dangerous".[1]

Medrano joined the Gulf Cartel during the 1990s when Juan García Ábrego was in power. After García Ábrego was arrested in 1996, the cartel experienced internal strife as several factions and leaders vied for control. Medrano was part of a faction which fought other groups headed by cartel leaders Ángel Salvador Gómez Herrera ("El Chava"), Gilberto García Mena ("El June"), and Hugo Baldomero Medina Garza ("El Señor de los Tráilers") for control of the drug corridors in a region in Tamaulipas known as La Frontera Chica. Control of the cartel solidified under Osiel Cárdenas Guillén in 1998[2] and Medrano began working for him.[3] Medrano and Cárdenas met when they worked for the Federal Judicial Police (PJF) in Tamaulipas.[4] Under Cárdenas, Medrano reported to Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez ("El Coss") and Víctor Manuel Vázquez Mireles ("El Meme"). Based in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, he was part of groups known as Sierras and Tangos. Their members used aliases and codes to ensure anonymity.[lower-alpha 1][3] His roles in the cartel were managing death orders from Cárdenas and overseeing drug distribution from Matamoros.[5] He also coordinated cash shipments of drug proceeds from the U.S. to Mexico,[6] and verified the quality and amount of narcotics received from Guatemala to Chiapas, from where it was later sent to northern Mexico.[7]

On 9 November 1999,[8] Medrano and several associates, including Cárdenas, threatened two U.S. agents at gunpoint in Matamoros.[9][10] The agents, who had traveled there with an informant to gather intelligence on the cartel's operations, were intercepted by the Gulf Cartel. Although Cárdenas threatened to kill the agents and informant during the standoff, after a heated discussion they were allowed to return to the U.S. unharmed.[11] The incident led to increased law-enforcement efforts against the Gulf Cartel's leadership.[12] On 14 March 2000, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas (S.D. Tex.) in Brownsville filed a sealed indictment against Medrano for multiple marijuana and cocaine trafficking offenses, a money laundering scheme, and for assaulting the two agents.[13] On 14 December 2000, the U.S. State Department announced a US$2 million bounty for Medrano, Cárdenas and José Manuel Garza Rendón ("La Brocha"), and unsealed the March indictment.[14][15] On 9 April 2002, Medrano was charged again by the S.D. Tex. in a superseding indictment.[13] The U.S. had an open extradition request, based on the Brownsville indictments.[16] In Mexico, Medrano was wanted for drug trafficking, illegal possession of firearms, attempted homicide and organized-crime involvement.[16] His arrest warrant was issued on 18 May 2000 by Judge Olga Sánchez Contreras of a Mexico City court.[17][18]

Medrano was promoted to second-in-command in the cartel after the April 2001 arrest of García Mena.[19][20] He took over drug trafficking in the state of Veracruz, where the cartel bought drug shipments from Colombian drug cartels for distribution.[21] After Garza Rendón surrendered to U.S. authorities at the Texas border on 5 June 2001,[22] Medrano rose higher in the cartel.[16] On 14 January 2002 the Mexican Army arrested Rubén Sauceda Rivera ("El Cacahuate"), one of Medrano's associates in Matamoros,[23][24] and Medrano became a priority target for the Mexican government. Mario Roldán Quirino of the Attorney General's Office (PGR) headed Medrano's investigation.[25] Mexican security forces worked with U.S. law-enforcement agencies, sharing intelligence to find and apprehend Medrano.[26] Although Roldán visited Matamoros in December 2001 and made significant progress in the investigation,[21][25] he was murdered in Mexico City by reported organized-crime figures on 21 February 2002,[27][28] a few months before Medrano was captured.[25]

Arrest and reaction

After months of being tracked,[29] Medrano was arrested by the Mexican Army and the Federal Investigation Agency (AFI) in Matamoros on 27 March 2002.[20] The arrest occurred in the Buena Vista neighborhood at around 4:00 p.m.;[30][31] he was detained while buying ice cream with his son and wife.[20][30] No shots were fired,[32] and Medrano did not resist arrest. Officials said that the non-violent arrest was a result of successful intelligence-gathering; they learned that he was trying to live an apparently-ordinary life in Matamoros, with few luxuries, to avoid attracting attention.[33] However, rumors began that his arrest may have been a handover by the Gulf Cartel and not the result of law-enforcement intelligence. Authorities denied the allegations, confirming their efforts against Medrano and denying speculation that he surrendered.[30][20] The rumors stemmed from the fact that Medrano was arrested without bodyguards and without any shots fired.[lower-alpha 2][30]

At the scene, authorities discovered that Medrano was driving a Suburban without license plates.[34] He had a special-edition, gold-plated .38 handgun and seven cartridges.[35][36] According to Estuardo Mario Bermúdez Molina, former head of the Special Prosecutor's Office for Crimes against Health (FEADS, an anti-narcotics agency of the PGR), several men tried to bribe police officers to release Medrano and the officers called for reinforcements.[30] Police confirmed that several vehicles followed the police car carrying Medrano, but the followers never shot at the police units. Authorities asked for reinforcements while they traveled in a convoy, forming a barricade to protect Medrano's vehicle.[35] The element of surprise delayed any attempts by the Gulf Cartel to release him. When Medrano was in custody at a military installation, a large group of people asked for him. An official did not confirm if they were part of the Gulf Cartel, saying that they did not try to release him.[30] Authorities confirmed that some informants who provided information leading to Medrano's arrest would receive part of the $2 million bounty;[16] law-enforcement personnel, however, were ineligible for the reward.[34]

During the 2000s, the Mexican government arrested a number of other high-ranking alleged organized-crime figures.[37][38] With Medrano's arrest, Mexican President Vicente Fox indicated a strategy shift from previous administrations against drug cartels by targeting several cartels at a time instead of only one.[39][40] Fox's administration was more successful than those of his predecessors, Ernesto Zedillo and Carlos Salinas de Gortari, in high-profile drug arrests.[41] At a press conference, Bermúdez said that Medrano's arrest dealt a "substantial" blow to the Gulf Cartel.[42][43] Authorities were concerned that arrests like Medrano's would trigger infighting among the Gulf Cartel leadership,[44][45] and speculated that the cartel would experience important executive changes. One leader expected to fill Medrano's position was Gregorio Sauceda Gamboa ("El Caramuela"), who was based in Reynosa, Tamaulipas.[5] Investigators also considered Costilla Sánchez and Vázquez Mireles as possible successors.[5][46]

Custody and imprisonment

Medrano was held at a military facility in Matamoros before being transferred to Mexico City for processing.[17] His first hearing was held on 29 March 2002 in front of the judge Alfredo Belmont,[47] and his attorney said that his client would remain silent.[18] In one of his hearings, Medrano told the prosecution he was a legitimate businessman and said that the evidence against him were nonexistent.[48] He asked authorities to immediately release him. The two U.S. agents and their informant, however, testified against Medrano and explained to the prosecution the details of the standoff where Medrano and other Gulf Cartel members threatened them at gunpoint. Medrano's defense claimed that the case against their client did not include information of the death threats against the two U.S. agents or of gun possession.[47]

Medrano was confined at the Reclusorio Oriente, a penitentiary in Mexico City, under the jurisdiction of the district criminal court.[24] Unlike most inmates at the prison, Medrano was under constant supervision.[lower-alpha 3][49] Authorities discussed the possibility of transferring him to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 1 (formerly known as La Palma),[50] a maximum-security prison in Almoloya de Juárez, State of Mexico, because Medrano was considered dangerous.[30] However, the transfer required a ruling by a federal judge.[35] In Reclusorio Oriente, Medrano became close friends with drug lords Luis Eusebio Duque Reyes ("El Duke") and Juan José Quintero Payán.[lower-alpha 4] The alliances worried prison personnel, who believed that they posed a risk to the penitentiary.[51] At Reclusorio Oriente, Medrano and thirty-two other inmates wrote a letter to the government complaining about alleged corruption and abuses in the prison under director Rubén Fernández Lima.[54]

Conviction and release

On 6 October 2003, a federal court in the State of Mexico convicted Medrano of illegal possession of firearms.[55] He was sentenced to six years and three months in prison.[56] Medrano also received a minimum-wage sentence of 87 days, meaning he was ordered to pay N$3,677 (US$2,530 in October 2003) in fines. According to the PGR, Medrano had a pending extradition request from the U.S. government for drug-trafficking and assault charges.[57] On 11 May 2006, a federal judge in Toluca, State of Mexico increased his sentence to 44 years.[58][59] Medrano was found guilty of organized-crime involvement, attempted homicide, and illegal possession of firearms.[60] His drug-trafficking charges were pending resolution at the time of the sentence.[61] In addition to imprisonment, Medrano received a minimum-wage sentence of 350 days.[59]

He remained at Reclusorio Oriente until 14 January 2009, when a federal judge approved his transfer to the Federal Social Readaptation Center No. 4, (also known as "El Rincón"), a maximum-security prison in Tepic, Nayarit. His transfer was coordinated by Mexico City officials and federal agents, who brought him from Reclusorio Oriente to Mexico City International Airport for a flight to Nayarit. Eleven other inmates from Reclusorio Oriente, Reclusorio Norte, and Reclusorio Sur were also transferred to Nayarit by law enforcement.[62] The transfer of Medrano and other high-profile criminals to El Rincón caused an uproar by Nayarit officials because of the criminals' high-profile statuses, which they believed worsen Nayarit's reputation; former Nayarit governor Ney González Sánchez complained about the transfers, which were approved by the federal government without his input.[63]

During his imprisonment, Medrano's defense prevented his extradition to the U.S.[64] Between 2012 and 2014, Medrano and nine other high-profile criminals were unexpectedly released from prison before serving their sentences;[lower-alpha 5] only one was re-arrested and re-imprisoned. In some of the cases, judges ordered releases because of violations of due process, fallacious protected-witness testimony, and arrests made without warrants.[65] The reviews were conducted as a result of Mexico's New Criminal Justice System (Nuevo Sistema de Justicia Penal, or NSJP).[66] The reason for Medrano's release was not specified.[65]

See also

Sources

Footnotes

- His immediate coworkers were Gabriel ("Tango 48"); Arteaga ("Tango 58"); El Viejo Fox, El Mano, El Chuqui; David ("El Davis"); Rubén Sauceda Rivera ("Tango 50"); El Güerco, El Puma; Jorge Esteban Pacheco Rivera ("El Doble Cero"); César Eduardo García Martínez ("Tango 95"); Antonio Galarza ("El Amarillo"), and Galo Gaspar ("El Licenciado Galo").[3]

- The rumors stemmed from the arrests of Tijuana Cartel drug lords Benjamín Arellano Félix and Alcides Ramón Magaña, who were also arrested without bodyguards or gunfire.[30]

- Other prisoners under constant supervision were Argentine national Ricardo Miguel Cavallo and the Juárez Cartel drug lord Juan José Quintero Payán.[49]

- The cited source names Emilio Quintero Payán[51] (Juan José's brother who was killed in 1993),[52][53] but Juan José and Medrano were at Reclusorio Oriente at the same time.[49]

- The other nine were Rafael Caro Quintero of the Guadalajara Cartel; Arturo Hernández González ("El Chaki") of the Juárez Cartel; Ricardo García Urquiza of the Juárez Cartel; José Gil Caro Quintero of the Sinaloa Cartel; Roberto Beltrán Burgos ("El Doctor") of the Sinaloa Cartel; Carlos Rosales Mendoza of La Familia Michoacana; Rogelio González Pizaña of the Gulf Cartel, and Martín Alejandro Beltrán Coronel and Jesús Albino Quintero Meraz of the Sinaloa Cartel.[65]

References

- "Operation Impunity II". Drug Enforcement Administration. December 2000. Archived from the original on 5 July 2003.

- Castillo García, Gustavo; Torres Barbosa, Armando (15 March 2003). "La historia del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 December 2018.

- Réyez, José (31 August 2009). "Las operaciones secretas del cártel del Golfo". Contralinea (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 July 2021.

- Vicenteño, David (29 March 2002). "De tráfico de armas a drogas". Palabra (in Spanish). Saltillo, Coahuila: Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 377437895.

- Ramírez, Juan José (30 March 2002). "Un cártel en reacomodo". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City: Infoshare Communications Inc. ProQuest 310821183.

- Otero, Silvia (11 May 2006). "Sentenciado El Licenciado a 44 años de prisión". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 March 2019.

- "Sentencian a 44 años de cárcel a colaborador de Cárdenas Guillén". El Periódico de México (in Spanish). 11 May 2006. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019.

- Tarricone, Celeste (27 March 2002). "Key Mexican Drug Suspect Arrested". Midland Reporter-Telegram. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019.

- Weiner, Tim (29 March 2002). "Mexico Arrests A Key Figure in Drug Cartel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018.

- Medellín, Alejandro (28 March 2002). "Adán Medrano, una historia criminal". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 November 2018.

- Schiller, Dane (15 March 2010). "DEA agent breaks silence on standoff with cartel". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018.

- Golden, Tim (24 November 1999). "Head to Head in Mexico: D.E.A. Agents And Suspects". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017.

- "United States of America v. Cardenas-Guillen, et al" (PDF). United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas. 10 March 2010. pp. 22–25, 46–53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2019 – via Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

- "$2 Million Reward Offered Leading to the Arrest or Conviction of Drug Traffickers". Drug Enforcement Administration. 14 December 2000. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- Sheridan, Mary Beth (15 December 2000). "U.S. Targets Alleged Mexican Drug Kingpin". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015.

- Tarricone, Celeste (29 March 2002). "Drug trafficking suspect arrested; Mexico: U.S. had offered $2 million reward". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "Cae operador del Cártel del Golfo". El Mexicano (in Spanish). 29 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Vicenteño, David (29 March 2002). "Cae capo de Cártel del Golfo". Mural (in Spanish). Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 373905252.

- Franco, Pilar (10 April 2001). "Army Deals Major Blow to 'Gulf Cartel'". Inter Press Service. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- "Capturan a 'El Licenciado', segundo hombre del Cártel del Golfo". Proceso (in Spanish). 29 March 2002. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018.

- Medellín, Jorge Alejandro (29 March 2002). "Cae otro operador de Osiel Cárdenas". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 January 2019.

- "Alleged Cartel lieutenant surrenders Drugs: Wanted man walks across Pharr bridge and turns himself in". The Brownsville Herald. 7 June 2001. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Detienen al cerebro financiero del cártel del Golfo, Rubén Sauceda Rivera". Proceso (in Spanish). 16 January 2002. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Dávila, Darío (28 March 2002). "Detienen al operador del Cártel del Golfo". La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Vicenteño, David; Ramírez, Juan José (29 March 2002). "Cerca y captura Fiscal al capo Adán Medrano". Mural (in Spanish). Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 374050471.

- Caparini 2006, p. 278.

- Bolaños, Ángel; Castillo, Gustavo; Baltazar, Elia (21 February 2002). "Asesinan a funcionario de FEADS; ejecución del narco, señalan en PGR". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Hernández López, Julio (29 March 2002). "Astillero: Adán Medrano Rodríguez". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 January 2019.

- "Confirma la PGR la detención de Adán Medrano, miembro del cártel del Golfo". Proceso (in Spanish). 28 March 2002. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018.

- Lira Saade, Carmen (29 March 2002). "Detiene la PGR en Matamoros a Adán Javier Medrano, uno de los jefes del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 January 2019.

- "Capturan a capo de cártel del Golfo". El Universal (in Spanish). 28 March 2002. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019.

- Zárate Ruiz 2003, p. 153.

- Domínguez F., José Miguel (29 March 2002). "Capturan a segundo jefe del Cártel del Golfo". Panamá América (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Narcía, Elva (28 March 2002). "Golpe al narcotráfico en México" (in Spanish). BBC Mundo. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017.

- Dávila, Darío (29 March 2002). "Capturan a Adán Medrano y quiebran al cártel del Golfo". La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 November 2018.

- "Síntesis del mundo: golpe al narco". La Nación (in Spanish). 30 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- "Paso a paso el gobierno mexicano asesta duros golpes al narcotráfico". La Hora (in Spanish). 31 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Raat 2004, p. 212.

- "Mexico nabs another drug cartel suspect". New York Times News Service. 29 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- IMEP 2001, p. na.

- Barajas, Abel (30 March 2002). "Gana Fox en golpes al narco". El Norte (in Spanish). Infoshare Communications Inc. ProQuest 315974353.

- Kraul, Chris (29 March 2002). "Mexico Captures No. 2 Leader of Gulf Drug Cartel". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017.

- "'Drug lord' arrested in Mexico". BBC News. 28 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016.

- "Mexico makes big gains in fighting drug cartels". The Baltimore Sun. 31 March 2002. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Astorga, Luis; Shirk, David (22 December 2010). "Drug Trafficking Organizations and Counter-Drug Strategies in the U.S.-Mexican Context" (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. pp. 40–42. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017.

- Medellín, Jorge (28 March 2002). "Medrano tendría ya sucesor en cártel". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 January 2019.

- Gómez, Francisco (29 March 2002). "Asegura El Licenciado ser comerciante". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 March 2019.

- Medellín, Alejandro; Gómez, Francisco (29 March 2002). "Nuevo golpe al Cártel del Golfo; cae otro capo". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 November 2018.

- Fernández, Leticia (22 January 2003). "Prevén benefico el nuevo penal". Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 307069373.

- "El Licenciado sigue aún en Reclusorio Oriente". La Jornada (in Spanish). 2 April 2002. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019.

- López, Yáscara (25 June 2015). "Adjudican a ex recluso amenazas a funcionarios". Reforma (in Spanish). Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 1691027703.

- Cisneros, Jorge (31 October 1999). "Aprehendió la PGR a presunto integrante del cártel de Juárez". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- "Muerto barón mexicano de la coca". El Tiempo (in Spanish). 5 May 1993. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018.

- Badillo, Miguel (24 November 2009). "La PGR es un centro de delincuentes". Zócalo Saltillo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 January 2019.

- Sevilla, Ramón (6 October 2003). "Dan seis años a un operador del capo Osiel". Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Jalisco: Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 374166194.

- "Dictan sentencia a operador del cártel del Golfo". El Universal (in Spanish). 5 October 2003. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019.

- Sevilla, Ramón (6 October 2003). "Condenan a capo a 6 años de prisión". Palabra (in Spanish). Editora El Sol, S.A. de C.V. ProQuest 377347332.

- "Drug lord cohort sentenced". The Denver Post. Associated Press. 11 May 2006. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Torres, Rubén (12 May 2006). "Sentencian a operador de Cártel del Golfo". El Economista (in Spanish). Mexico City. ProQuest 336467039.

- Castillo, Gustavo (12 May 2006). "Pena de 44 años de cárcel a operador del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 January 2019.

- "Sentencian a capo a 44 años de prisión". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). 12 May 2006. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018.

- López, Mae (14 January 2009). "Trasladan a brazo derecho de Osiel Cárdenas al penal de Nayarit". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 May 2012.

- "Crece 'fama' de Nayarit por la cárcel federal de El Rincón". Nayarit En Línea (in Spanish). 20 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- "En las cárceles, poder narco". Proceso (in Spanish). 21 August 2005. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017.

- Barajas, Abel (27 October 2014). "Liberan a 10 capos en 2 años". El Mural (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Monroy, Jorge (5 March 2015). "Los narcos más temidos que han sido liberados". El Economista (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 January 2019.

Bibliography

- Caparini, Marina (2006). Borders and Security Governance: Managing Borders in a Globalised World. LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3037350058.

- IMEP (2001). Política mexicana: Perspectiva política (in Spanish). Instituto Mexicano de Estudios Políticos.

- Raat, William Dirk (2004). Mexico and the United States: Ambivalent Vistas. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820325953.

- Zárate Ruiz, Arturo (2003). La ley de Herodes y la 'guerra' contra las drogas (in Spanish). Plaza y Valdés Editores. ISBN 9707221615.

Further reading

- Deibert, Michael (2014). In the Shadow of Saint Death: The Gulf Cartel and the Price of America's Drug War in Mexico. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1493010653.

- Ravelo, Ricardo (2012). Osiel: Vida y tragedia de un capo (in Spanish). Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-6073107716.