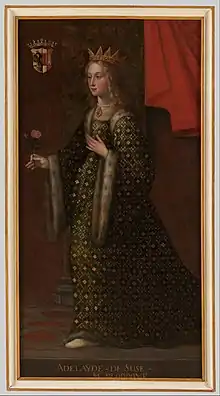

Adelaide of Susa

Adelaide of Turin (also Adelheid, Adelais, or Adeline; c. 1014/1020 – 19 December 1091)[1] was the countess of part of the March of Ivrea and the marchioness of Turin in Northwestern Italy from 1034 to her death. She was the last of the Arduinici.[2] She is sometimes compared to her second cousin and close contemporary, Matilda of Tuscany.[3]

Adelaide of Turin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1014/1020 Turin |

| Died | 19 December 1091 |

| Buried | Parochial church of Canischio (uncertain) |

| Noble family | Arduinici |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Issue | |

| Father | Ulric Manfred II of Turin |

| Mother | Bertha of Milan |

Biography

Early life

Born in Turin to Ulric Manfred II of Turin and Bertha of Milan around 1014/1020, Adelaide's early life is not well known.[4][5] Adelaide had two younger sisters, Immilla and Bertha. She may also have had a brother, whose name is not known, who predeceased her father.[6] Thus, upon Ulric Manfred II's death (in December 1033 or 1034), Adelaide inherited the bulk of her father's property.[7] This included property in the counties of Turin (especially in the Susa Valley), Auriate, and Asti. Adelaide also inherited property, but probably not comital authority, in the counties of Albenga, Alba, Bredulo and Ventimiglia.[8] It is likely that Adelaide's mother, Bertha, briefly acted as regent for Adelaide after Ulric Manfred's death.

Marriages

Since the margravial title primarily had a military purpose at the time, it was not considered a suitable position for a woman. Emperor Conrad II therefore arranged a marriage between Adelaide and his stepson, Herman IV, in 1036 or 1037. Herman was then invested as margrave of Turin.[9] However, in 1038, Herman died of the plague while fighting for Conrad II in Naples.

Adelaide remarried in order to secure her vast possessions. Probably in 1041, and certainly before 19 January 1042, Adelaide married Henry, Marquess of Montferrat.[10] Henry died around 1045 leaving Adelaide a widow for the second time. Immediately, a third marriage was undertaken, this time to Otto of Savoy (1046).[5] Adelaide had three sons with Otto: Peter I, Amadeus II, and Otto. They also had two daughters: Bertha, who married Henry IV of Germany, and Adelaide, who married Rudolf of Rheinfelden (who later opposed Henry as King of Germany).

Widowhood and rule

After the death of her husband Otto, c.1057/60, Adelaide ruled the march of Turin and the county of Savoy alongside her sons Peter and Amadeus.

It is sometimes said that Adelaide abandoned Turin as the capital and began to reside permanently at Susa. This is incorrect. Adelaide is documented far more frequently at the margravial palace in Turin than anywhere else.[11]

In 1070 Adelaide captured and burned the city of Asti, which had rebelled against her.[12]

Relationship with empire

In 1069 Henry IV tried to repudiate Adelaide's daughter, Bertha,[13] causing Adelaide's relationship with the imperial family to cool. However, through Bertha's intervention, Henry received Adelaide's support when he came to Italy to submit to Pope Gregory VII and Matilda of Tuscany at Canossa. In return for allowing him to travel through her lands, Henry gave Adelaide Bugey.[14] Adelaide and her son Amadeus then accompanied Henry IV and Bertha to Canossa, where Adelaide acted as mediator, alongside Matilda and Albert Azzo II, Margrave of Milan, among others.[15] Bishop Benzo of Alba sent several letters to Adelaide between 1080 and 1082 encouraging her to support Henry IV in the Italian wars which formed part of the Investiture Controversy.[16] Following this, Adelaide's dealings with Henry IV became closer. She offered to mediate between him and Matilda of Tuscany, and may even have joined him on campaign in southern Italy in 1084.[17]

Relationship with the Church

Adelaide made many donations to monasteries in the march of Turin. In 1064 she founded the monastery of Santa Maria at Pinerolo.[18]

Adelaide received letters from many of the leading churchmen of the day, including Pope Alexander II, Peter Damian,[19] and Pope Gregory VII.[16] These letters indicate that Adelaide sometimes supported Gregorian reform, but that at other times she did not. Peter Damian (writing in 1064) and Gregory VII (writing in 1073), relied upon Adelaide to enforce clerical celibacy and protect the monasteries of Fruttuaria and San Michele della Chiusa. By contrast, Alexander II (writing c.1066/7) reproached Adelaide for her dealings with Guido da Velate the simoniac Archbishop of Milan.

Death

Adelaide died in December 1091.[20] According to a later legend, she was buried in the parochial church of Canischio (Canisculum) in a small village on the Cuorgnè in the Valle dell'Orco, where she had supposedly been living incognito for twenty-two years before her death.[21] The medieval historian Charles William Previté-Orton called this story "absurd".[22] In the cathedral of Susa, in a niche in the wall, there is a statue of walnut wood, beneath a bronze veneer, representing Adelaide genuflecting in prayer. Above it is the inscription: Questa è Adelaide, cui l'istessa Roma Cole, e primo d'Ausonia onor la noma.[23]

Family and children

Due to a late Austrian source, Adelaide and Herman IV, Duke of Swabia are sometimes mistakenly said to have had children together.[24] This was not the case. Herman was on campaign for much of his short marriage to Adelaide and he died without heirs.[25] Nor did Adelaide have children with her second husband, Henry.

Adelaide and Otto of Savoy had five children:

- Peter I of Savoy (c. 1048 – 1078), married Agnes, daughter of William VII, Duke of Aquitaine.[26]

- Amadeus II of Savoy (c. 1050 – 1080)

- Otto[27]

- Bertha of Savoy (1051 – 1087), married Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, June 1066.[26]

- Adelaide of Savoy, married Rudolf von Rheinfelden[26]

Legacy

Adelaide is a featured figure on Judy Chicago's installation piece The Dinner Party, being represented as one of the 999 names on the Heritage Floor.[28][29] She is affiliated with the place setting of Eleanor of Aquitaine.[30]

References

- Previte-Orton, p250 note7; 19 December~Bernold, 25 December~Necrol. S. Solutoris etc. Turin

- Pennington, Reina (2003). Amazons to Fighter Pilots: An Autobiographical Dictionary of Military Women. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 3. ISBN 0313327076.

- See e.g. Fumagalli, 'Adelaide e Matilde'; Goez, 'Ein neuer Typ der europäischen Fürstin'; Sergi, 'Matilde di Canossa e Adelaide di Torino'

- Boyd 1943, p. 14.

- Dunbar, Agnes Baillie Cunninghame (1904). A Dictionary of Saintly Women. Bell.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 154, 187

- Sergi, I confini del potere, p. 81

- On the property inherited by Adelaide, see Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 154f., 188, 208, 217 and 231f.

- Hellmann, Grafen, p. 13

- Merlone, 'Prosopografia aleramica,' p. 580.

- Sergi, 'I poli del potere'.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 228f.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 232f; Creber, Alison (22 April 2019). "Breaking Up Is Hard To Do: Dissolving Royal and Noble Marriages in Eleventh-Century Germany". German History. 37 (2): 149–171. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghy108. ISSN 0266-3554..

- Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 237f.

- Creber, ‘Women at Canossa'; Hellmann, Grafen, pp. 24f

- For English translations of these letters, see Epistolae: Medieval Women's Latin Letters Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. For discussion, see: Creber, ‘The Princely Woman and the Emperor'.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 248f.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, p. 162

- Creber, 'Mirrors for Margraves'.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, p. 250.

- Chronicon Abbatiae Fructuariensis, in G. Calligaris, ed., Un’antica cronaca piemontese inedita (Turin, 1889), pp. 132f.

- Previté-Orton, Early History, pp. 250–251.

- Casalis, Goffredo, ed. (1850). Dizionario geografico-storico-statistico-commerciale degli stati del Redi Sardegna (in Italian). G. Maspers.

- On this see E. Hlawitschka, 'Zur Abstammung Richwaras, der Gemahlin Herzog Bertholds I. von Zähringen,' Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins, 154 (2006), 1–20

- Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln, I.1, table 84

- Previte-Orton, p.231.

- Otto is sometimes said to be Bishop Otto III of Asti (r.c.1080-c.1088), but this identification is uncertain. See L. Vergano, Storia di Asti, part I. (Asti, 1951)

- Chicago, 121.

- "Adelaide of Susa". Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor: Adelaide of Susa. Brooklyn Museum. 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- "Adelaide of Susa". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

Sources

- Boyd, Catherine Evangeline (1943). A Cistercian Nunnery in Mediaeval Italy: The Story of Rifreddo in Saluzzo, 1220-1300. Harvard University Press.

- H. Bresslau, Jahrbücher des Deutschen Reichs unter Konrad II., 2 vols. (1884), accessible online at: archive.org

- Chicago, Judy. The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation. London: Merrell (2007). ISBN 1-85894-370-1

- F. Cognasso, 'Adelaide' in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani- Volume 1 (1960)

- A. Creber, 'Breaking Up Is Hard To Do: Dissolving Royal and Noble Marriages in Eleventh-Century Germany', German History 37:2 (2018), pp. 149–171.

- A. Creber, ‘The Princely Woman and the Emperor: Imagery of Female Rule in Benzo of Alba’s Ad Heinricum IV,’ Royal Studies Journal 5:2 (2018), 7-26.

- A. Creber, ‘Women at Canossa. The Role of Elite Women in the Reconciliation between Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV of Germany (January 1077),’ Storicamente 13 (2017), article no. 13, pp. 1–44.

- A. Creber, 'Mirrors for Margraves: Peter Damian's Different Models for Male and Female Rulers,’ Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques, 42:1 (2016), 8-20.

- V. Fumagalli, 'Adelaide e Matilde, due protagoniste del potere medievale,’ in La contessa Adelaide e la società del secolo XI, a special edition of Segusium 32 (1992), 243-257

- E. Goez, 'Ein neuer Typ der europäischen Fürstin im 11. und frühen 12.Jahrhundert?’ in B. Schneidmüller and S. Weinfurter, eds., Salisches Kaisertum und neues Europa. Die Zeit Heinrichs IV. und Heinrichs V. (Darmstadt, 2007), pp. 161–193.

- S. Hellmann, Die Grafen von Savoyen und das Reich: bis zum Ende der staufischen Periode (Innsbruck, 1900), accessible online (but without page numbers) at: Genealogie Mittelalter

- R. Merlone, 'Prosopografia aleramica (secolo X e prima metà dell'XI),' Bollettino storico-bibliografico subalpino, LXXXI, (1983), 451-585.

- C.W. Previté-Orton, The Early History of the House of Savoy (1000–1233) (Cambridge, 1912), accessible online at: archive.org

- D. Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten (Marburg, 1978).

- G. Sergi, 'I poli del potere pubblico e dell'orientamento signorile degli Arduinici: Torino e Susa, in La contessa Adelaide e la società del secolo XI, a special edition of Segusium 32 (1992), pp. 61–76

- G. Sergi, I confini del potere. Marche e signorie fra due regni medievali (1995).

- G. Sergi, 'Matilde di Canossa e Adelaide di Torino: contatti, confronti, valutazioni tipologiche,’ in Matilde di Canossa e il suo tempo. Atti del XXI congresso internazionale di studio Sull’alto Medioevo (Spoleto, 2016), pp. 57–74.

External links

- Women's Biography: Adelaide of Turin and Susa (Brief biography of Adelaide, plus English translations of letters to Adelaide, and legal documents issued by Adelaide)

- Adelheid von Turin, Herzogin von Schwaben, Markgräfin von Turin, Gräfin von Savoyen

- Henry Gardiner Adams, ed. (1857). "Adelaide". A Cyclopaedia of Female Biography: 8. Wikidata Q115297411.