Adrenal haemorrhage

Adrenal hemorrhage (AH) is acute blood loss from a ruptured vessel of the adrenal glands above the kidneys.

It is a rare, yet potentially fatal event that could be caused by trauma and multiple non-traumatic conditions.[1] Despite the unclear etiology, there are several risk factors of adrenal hemorrhage, including birth trauma, sepsis, and hemorrhagic disorders.[2] Anoxia and sepsis are the most frequent causes at birth, while adrenal insufficiency often manifests in neonates.[3] Adrenal haemorrhage has been reported during COVID-19 infection and following Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination.[4]

According to the degree and rate of hemorrhage,[1] its clinical manifestations can vary widely. The non-specific signs and symptoms in prominent underlying diseases often prevent prompt recognition and proper treatment of the condition, which may result in adrenal crisis, shock, and death.[5] Although the mortality rate varies with the severity of the underlying inductive disease, adrenal hemorrhage is related to 15% of the deaths.[5]

In the US, the incidence rate is reported to be 0.3-1.8% based on unselected cases in autopsy studies.[5] In terms of age group, higher prevalence is found among neonates, with an incidence rate of 0.17% in infant autopsies and 3% in infant abdominal ultrasound examination.[6]

Diagnosis in the early phase is critical, though it is relatively rare due to non-characteristic clinical presentation and laboratory findings.[7] Imaging and laboratory studies are often employed for diagnosis and surveillance. Non-operative management has taken over surgical exploration and has become the main approach to treating both traumatic and non-traumatic adrenal hemorrhage.

Classification

Bilateral and Unilateral

Considering the site of bleeding, adrenal hemorrhage could be classified as unilateral and bilateral. The former type is more frequently reported.[1]

Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage is the condition when bleeding occurs in both adrenal glands, which could be instantly life-threatening. Over half of the bilateral cases are related to acute stress, such as infection, congestive myocardial infarction, complications of pregnancy, surgery or invasive procedure. Other common causes include hemorrhagic diatheses, thromboembolic diseases, blunt trauma, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) therapy. With sepsis, the mortality rate of this condition can reach 90%.[8]

Unilateral adrenal hemorrhage is the condition when bleeding occurs in either one of the adrenal glands, predominantly on the right that accounts for around three-quarters of the cases.[9] It is usually associated with blunt force abdominal trauma, primary adrenal or metastatic tumors, long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and adrenal vein thrombosis. Liver transplantation can occasionally cause unilateral adrenal hemorrhage as well, with 2% occurrence in the right adrenal gland in patients received liver transplantation.

Traumatic and non-traumatic

Adrenal hemorrhage is classified by its cause, traumatic or non-traumatic.

Trauma, either by blunt force or penetration, accounts for 80% of the cases.[10] Up to a quarter of severely injured patients suffer from adrenal hemorrhage.[11] Direct compression of adrenal glands and acute intravenous pressure rise due to compression of the inferior vena cava are the two proposed mechanisms of traumatic adrenal gland injury.[1]

Non-traumatic adrenal hemorrhage is an atypical type, which can be further categorised as acute stress and neonatal stress, anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), anti-coagulation, spontaneous, and tumor-related.

- Acute stress includes stress resulting from overwhelming sepsis, pregnancy, hypotension, and administration of ACTH, which gradually increases blood flow to the adrenal gland and glucocorticoid secretion, and leads to haemorrhage because of the higher pressure within the adrenal glands.[1] The cause of neonatal stress remains undetermined.

- Patients with APS are prone to recurring adrenal vein thrombosis that might cause hemorrhagic infarction of the adrenal gland,[1] making it a major risk factor of adrenal hemorrhage.

- Using anti-coagulant like heparin is also major cause of non-traumatic adrenal hemorrhage. For instance, heparin could lead to adrenal hemorrhage by potentiating the bleeding risk in patients with acute illness or inducing thrombocytopenia that causes thrombosis of the central adrenal vein.[12]

- The spontaneous type is an uncommon postoperative complication with subtle clinical findings,[13] which has higher occurrence in patients subjected to severe stress and may occur without potential inductive conditions.[13]

- In the cases with underlying tumors, benign lesions including adrenal cyst and myelolipoma bigger than 10 cm may spontaneously bleed into the adrenal gland or retroperitoneum. Massive bleeding from a primary adrenal tumor could be fatal in up to half of the reported cases, which are most resulted from pheochromocytoma.[14]

Pathophysiology

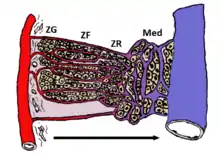

Adrenal gland is vulnerable to hemorrhage due to its special vascular supply. It has rich blood supply via 50 to 60 small arterial branches from three adrenal arteries. The branches then form a sub-capsular plexus within the adrenal cortex, which drains into medullary sinusoids through relatively fewer venules and flows into a single vein, creating a potential “vascular dam”.[15] The limited venous drainage builds the blood flow resistance and adrenal venous pressure, resulting in the hemorrhage into the gland.[1]

Under physiological stress, ACTH and catecholamine secretion increases, which further promotes adrenal arterial blood flow. Increased catecholamine level constricts the venules and enhances platelet aggregation, which may induce adrenal vein thrombosis. The synergistical effect builds up pressure within the venous sinusoids, predisposing to adrenal gland congestion and venous stasis.[5][16]

While the elevated intravascular pressure increases vascular wall tension proportionally, hemorrhage occurs when the tension within the thin adrenal venous walls exceeds their tolerance.[16] Under traumatic situations, direct compression between the spine and the abdominal organs cushioning adrenal glands, such as spleen and liver, could result in hemorrhage by increasing the intravascular pressure or cause vessel rupture directly.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Nonspecific pain is the most consistent symptom, with over 65% occurrence in published cases.[5] Meanwhile, fever happens most frequently, presenting in 50-70% of patients with adrenal hemorrhage.[5] Other symptoms of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage include adrenal insufficiency, tachycardia (as reported in 40-50% patients in early phases, can develop into shock),[5]hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, pre-renal azotemia, acidosis and positive ACTH stimulation test.[5][8] These symptoms can also be present in other adrenal abnormalities and are difficult to be differentiated from underlying conditions resulting in adrenal insufficiency. For unilateral adrenal hemorrhage, it does not show biochemically significant conditions.[8]

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies

Laboratory test findings are non-specific. Identification of adrenal hemorrhage cannot rely on laboratory findings alone.

Several signs of adrenal hemorrhage can be observed through blood tests. At least 4% decrease in hematocrit (i.e. volume of erythrocytes to total blood volume ratio), and a minimum of 2g/dL decrease in hemoglobin are observed in around half of the patients with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.[5] Leukocytosis is a frequently occurring condition, which may be related to the predisposing condition.[5]

Imaging

Pre-mortem diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage relies mainly on cross-sectional imaging, namely computed tomography (CT) scanning, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Adrenal hemorrhage could be detected by showing non-specific enlargement and hemorrhage into one or both adrenal glands in images.

CT scanning is the most common imaging test screening for adrenal hemorrhage. Its rising availability has facilitated pre-mortem diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage that is featured by a round or oval mass at the adrenal gland.[1]

Appearance of adrenal hematomas are in large number, but with low similarity.[8] Some of the patterns are distinct in adrenal hemorrhage while the other are undifferentiated from other adrenal abnormalities, such as adrenal neoplasm, adrenocortical carcinomas, and pheochromocytomas.[8] Hematomas have solid adrenal nodules, size of which are comparable to soft tissue and diminish over time. Partially solid and partially cystic lesions can present in many adrenal abnormalities. Compared to neoplasm, hematomas show higher density in pre-contrast scans with solid components tending to locate peripherally while fluid locating centrally.[8]

Retroperitoneal ill-defined soft tissue stranding is developed in around 90% of traumatic adrenal hemorrhage cases due to infiltration of blood through the retroperitoneal fat. Diffuse thickening of adrenal glands bilaterally can be observed.[16]

Adrenal hematomas with active hemorrhage are the most critical pattern to recognize. It is a rare condition, yet emergent embolization is required.[8]

Abdominal ultrasound examination serves as an effective non-invasive diagnostic tool for adrenal hemorrhage. Because of the non-exposure to ionizing radiation and a relatively high neonatal adrenal gland size to body size ratio that is sufficient for examination, ultrasound would be the preference for newborn patients.[17] An adrenal hemorrhage appears as a mass superior to the fetal kidneys.[9] The time-dependent variation of echogenicity patterning (i.e. echotexture) and hematoma size of its sequential sonographic appearance helps indicate the stage of hemorrhage.[14] In the early stage, hematoma of the adrenal gland appears solid with diffuse or heterogenous echogenicity, the ability to return a signal in the ultrasound examination.[1] As the lesion liquefies, a hypoechoic centre is developed. At last, the lesion would become entirely anechoic, with or without septations. Color Doppler could be used to confirm the absence of associated intrinsic vascularity of the lesion at different stages. Besides, the adrenal hematoma might calcify during the resolution phase, and the retroperitoneal calcifications are often peripheral and look egg-shaped.[5]

Other methods are adopted as the patients grow because the imaging of adrenal gland would become more difficult with ultrasound.

MRI is the most sensitive and specific method for adrenal hemorrhage diagnosis.[18] On MRI, haemorrhages could appear as different signals in the acute, subacute and chronic stages, which facilitates the surveillance of adrenal hemorrhage aging. In the acute stage, which is within the first week after onset, the adrenal hematomas appear isointense or slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images, and notably hypointense on T2-weighted images relative to liver.[1] This is resulted from the high concentration of intracellular deoxyhemoglobin that leads to preferential T2 proton relaxation enhancement.[14]

Progressing to the subacute stage, the following six weeks, hemoglobin oxidizes upon aging. This produces methemoglobin whose paramagnetic effect results in hematomas appearing hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images.[14]

In the chronic stage, the periphery of adrenal hematoma gradually becomes hyperintense, leaving a hypointense rim on T1- and T2-weighted images due to the hemosiderin deposition and development of a fibrous capsule.[14]

Management

In most literature, surgery is frequently adopted among the cases involving trauma-associated adrenal hemorrhage. It treats the hemorrhage by adrenal repair or adrenalectomy, depending on the extent of injury, the viability of residual adrenal tissue, the status of contralateral adrenal gland, and the stability of the patient.[1] Adrenal repair included closing the adrenal capsule with running non-absorbable suture, and placing interrupted mattress sutures when needed.[1] Adrenalectomy could be either unilateral or bilateral, the surgical removal of namely one or both adrenal glands.

Non-operative management can treat most of the adrenal haemorrhage cases nowadays,[1] both traumatic and non-traumatic. A larger proportion of patients have been successfully cured with surveillance while more reports suggested that surgical intervention is not needed.[19] Some adrenal injured trauma patients with absence of continuous bleeding are suggested to take non-operative management, when there is no other indication for abdominal exploration.[20] Supportive care, serial hematocrit measurement, and administration of blood transfusions upon needs constitute the non-operative management.[1]

Timely steroid replacement is a non-operative treatment targeting bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, which is crucial for survival.[8] Intravenous hydrocortisone and fluid resuscitation with normal saline are also preferred regarding this type.[21] For patients with suspected acute, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, administration of glucocorticoids is suggested to prevent or alleviate acute adrenal insufficiency.[5]

Follow-up surveillance by serial CT scanning and MRI also plays a critical role in adrenal hemorrhage non-operative management. By assessing the resolution and size of hematoma to track the temporal evolution of an adrenal hemorrhage, the benign adrenal hematoma could be differentiated from a pre-existing mass lesion that requires surgical removal.[1]

See also

References

- Simon DR, Palese MA (January 2009). "Clinical update on the management of adrenal hemorrhage". Current Urology Reports. 10 (1): 78–83. doi:10.1007/s11934-009-0014-y. PMID 19116100. S2CID 19336379.

- Donovan BO, Ramji F, Frimberger D, Kropp BP (2010-01-01). "Chapter 54: Neonatal Urologic Emergencies". In Gearhart JP, Rink RC, Mouriquand PD (eds.). Pediatric Urology (Second ed.). W.B. Saunders. pp. 709–719. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-3204-5.00054-2. ISBN 978-1-4160-3204-5. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Gleason CA, Juul SE (21 November 2017). Avery's diseases of the newborn (Tenth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 978-0-323-40172-2. OCLC 1013816550.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Elhassan, Yasir S.; Iqbal, Fizzah; Arlt, Wiebke; Baldeweg, Stephanie E.; Levy, Miles; Stewart, Paul M.; Wass, John; Pavord, Sue; Aled Rees, D.; Ronchi, Cristina L. (5 February 2023). "COVID‐19‐related adrenal haemorrhage: Multicentre UK experience and systematic review of the literature". Clinical Endocrinology. 98 (6): 766–778. doi:10.1111/cen.14881. ISSN 0300-0664. PMID 36710422. S2CID 256387753.

- Tritos NA (Oct 2018). "Adrenal Hemorrhage". Medscape. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Qureshi UA, Ahmad N, Rasool A, Choh S (October 2009). "Neonatal adrenal hemorrhage presenting as late onset neonatal jaundice". Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons. 14 (4): 221–3. doi:10.4103/0971-9261.59607. PMC 2858887. PMID 20419026.

- Di Serafino M, Severino R, Coppola V, Gioioso M, Rocca R, Lisanti F, Scarano E (September 2017). "Nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage: the adrenal stress". Radiology Case Reports. 12 (3): 483–487. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2017.03.020. PMC 5551907. PMID 28828107.

- Sacerdote MG, Johnson PT, Fishman EK (January 2012). "CT of the adrenal gland: the many faces of adrenal hemorrhage". Emergency Radiology. 19 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1007/s10140-011-0989-9. PMID 22037994. S2CID 26811560.

- Goel A, Weerakkody Y. "Fetal Adrenal Haemorrhage". Radiopaedia. Radiopaedia Org. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Mayo-Smith WW, Boland GW, Noto RB, Lee MJ (2001-07-01). "State-of-the-art adrenal imaging". Radiographics. 21 (4): 995–1012. doi:10.1148/radiographics.21.4.g01jl21995. PMID 11452074.

- Dewbury K, Rutherford EE (2011-01-01), Allan PL, Baxter GM, Weston MJ (eds.), "CHAPTER 33 - Adrenals", Clinical Ultrasound (Third Edition), Churchill Livingstone, pp. 632–642, ISBN 978-0-7020-3131-1, retrieved 2020-04-06

- Kurtz LE, Yang S (June 2007). "Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage associated with heparin induced thrombocytopenia". American Journal of Hematology. 82 (6): 493–4. doi:10.1002/ajh.20884. PMID 17266058.

- Clark OH (August 1975). "Postoperative adrenal hemorrhage". Annals of Surgery. 182 (2): 124–9. doi:10.1097/00000658-197508000-00007. PMC 1343829. PMID 1211987.

- Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Ernst RD, Takahashi N, Roubidoux MA, Goldman SM, et al. (1999-07-01). "Imaging of nontraumatic hemorrhage of the adrenal gland". Radiographics. 19 (4): 949–63. doi:10.1148/radiographics.19.4.g99jl13949. PMID 10464802.

- Rao RH, Vagnucci AH, Amico JA (February 1989). "Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage: early recognition and treatment". Annals of Internal Medicine. 110 (3): 227–35. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-110-3-227. PMID 2643380.

- Tan GX, Sutherland T (February 2016). "Adrenal congestion preceding adrenal hemorrhage on CT imaging: a case series". Abdominal Radiology. 41 (2): 303–10. doi:10.1007/s00261-015-0575-9. PMID 26867912. S2CID 10117657.

- Sarnaik AP, Sanfilippo DJ, Slovis TL (1988). "Ultrasound diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage in meningococcemia". Pediatric Radiology. 18 (5): 427–8. doi:10.1007/BF02388056. PMID 3050849. S2CID 32310555.

- Sayit AT, Sayit E, Gunbey HP, Aslan K (February 2017). "Imaging of unilateral adrenal hemorrhages in patients after blunt abdominal trauma: Report of two cases". Chinese Journal of Traumatology = Zhonghua Chuang Shang Za Zhi. 20 (1): 52–55. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.05.002. PMC 5343102. PMID 28196654.

- Chen KT, Lin TY, Foo NP, Lin HJ, Guo HR (May 2007). "Traumatic adrenal haematoma: a condition rarely recognised in the emergency department". Injury. 38 (5): 584–7. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2007.01.009. PMID 17472794.

- Udobi KF, Childs EW (September 2001). "Adrenal crisis after traumatic bilateral adrenal hemorrhage". The Journal of Trauma. 51 (3): 597–600. doi:10.1097/00005373-200109000-00036. PMID 11535920.

- Fatima Z, Tariq U, Khan A, Sohail MS, Sheikh AB, Bhatti SI, Munawar K (June 2018). "A Rare Case of Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage". Cureus. 10 (6): e2830. doi:10.7759/cureus.2830. PMC 6101466. PMID 30131923.