Incidental imaging finding

In medical or research imaging, an incidental imaging finding (also called an incidentaloma) is an unanticipated finding which is not related to the original diagnostic inquiry. As with other types of incidental medical findings, they may represent a diagnostic, ethical, and philosophical dilemma because their significance is unclear. While some coincidental findings may lead to beneficial diagnoses, others may lead to overdiagnosis that results in unnecessary testing and treatment, sometimes called the "cascade effect".[1]

Incidental findings are common in imaging. For instance, around 1 in every 3 cardiac MRIs result in an incidental finding.[2] Incidence is similar for chest CT scans (~30%).[2]

As the use of medical imaging increases, the number of incidental findings also increases.

Adrenal

Incidental adrenal masses on imaging are common (0.6 to 1.3% of all abdominal CT). Differential diagnosis include adenoma, myelolipoma, cyst, lipoma, pheochromocytoma, adrenal cancer, metastatic cancer, hyperplasia, and tuberculosis.[3] Some of these lesions are easily identified by radiographic appearance; however, it is often adenoma vs. cancer/metastasis that is most difficult to distinguish. Thus, clinical guidelines have been developed to aid in diagnosis and decision-making.[4] Although adrenal incidentalomas are common, they are not commonly cancerous - less than 1% of all adrenal incidentalomas are malignant.[2]

The first considerations are size and radiographic appearance of the mass. Suspicious adrenal masses or those ≥4 cm are recommended for complete removal by adrenalectomy. Masses <4 cm may also be recommended for removal if they are found to be hormonally active, but are otherwise recommended for observation.[5] All adrenal masses should receive hormonal evaluation. Hormonal evaluation includes:[6]

- 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test

- 24-hour urinary specimen for measurement of fractionated metanephrines and catecholamines

- Blood plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma renin activity, if hypertension is present

On CT scan, benign adenomas typically are of low radiodensity (due to fat content). A radiodensity equal to or below 10 Hounsfield units (HU) is considered diagnostic of an adenoma.[7] An adenoma also shows rapid radiocontrast washout (50% or more of the contrast medium washes out at 10 minutes). If the hormonal evaluation is negative and imaging suggests benign lesion, follow up may be considered. Imaging at 6, 12, and 24 months and repeat hormonal evaluation yearly for 4 years is often recommended,[6] but there exists controversy about harm/benefit of such screening as there is a high subsequent false-positive rate (about 50:1) and overall low incidence of adrenal carcinoma.[8]

Brain

Autopsy series have suggested that pituitary incidentalomas may be quite common. It has been estimated that perhaps 10% of the adult population may harbor such endocrinologically inert lesions.[9] Most of these lesions, especially those which are small, will not grow. However, some form of long-term surveillance has been recommended based on the size and presentation of the lesion.[10] With pituitary adenomas larger than 1cm, a baseline pituitary hormonal function test should be done, including measurements of serum levels of TSH, prolactin, IGF-1 (as a test of growth hormone activity), adrenal function (i.e. 24 hour urine cortisol, dexamethasone suppression test), testosterone in men, and estradiol in amenorrheic women.[11]

Thyroid and parathyroid

Incidental thyroid masses may be found in 9% of patients undergoing bilateral carotid duplex ultrasonography.[12]

Some experts[13] recommend that nodules > 1 cm (unless the TSH is suppressed) or those with ultrasonographic features of malignancy should be biopsied by fine needle aspiration. Computed tomography is inferior to ultrasound for evaluating thyroid nodules.[14] Ultrasonographic markers of malignancy are:[15]

- solid hypoechoic appearance

- irregular or blurred margins

- intranodular vascular spots or pattern

- microcalcifications

Incidental parathyroid masses may be found in 0.1% of patients undergoing bilateral carotid duplex ultrasonography.[12]

The American College of Radiology recommends the following workup for thyroid nodules as incidental imaging findings on CT, MRI or PET-CT:[16]

| Features | Workup |

|---|---|

|

Very likely ultrasonography |

| Multiple nodules | Likely ultrasonography |

| Solitary nodule in person younger than 35 years old |

|

| Solitary nodule in person at least 35 years old |

|

Pulmonary

Studies of whole body screening computed tomography find abnormalities in the lungs of 14% of patients.[17] Clinical practice guidelines by the American College of Chest Physicians advise on the evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule.[18]

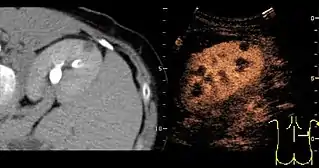

Kidney

Most renal cell carcinomas are now found incidentally.[19] Tumors less than 3 cm in diameter less frequently have aggressive histology.[20]

A CT scan is the first choice modality for workup of solid masses in the kidneys. Nevertheless, hemorrhagic cysts can resemble renal cell carcinomas on CT, but they are easily distinguished with Doppler ultrasonography (Doppler US). In renal cell carcinomas, Doppler US often shows vessels with high velocities caused by neovascularization and arteriovenous shunting. Some renal cell carcinomas are hypovascular and not distinguishable with Doppler US. Therefore, renal tumors without a Doppler signal, which are not obvious simple cysts on US and CT, should be further investigated with contrast-enhanced ultrasound, as this is more sensitive than both Doppler US and CT for the detection of hypovascular tumors.[21]

Spinal

The increasing use of MRI, often during diagnostic work-up for back or lower extremity pain, has led to a significant increase in the number of incidental findings that are most often clinically inconsequential. The most common include:[22]

- vertebral hemangioma

- fibrolipoma (a lipoma with fibrous areas)

- Tarlov cyst

Sometimes normally asymptomatic findings can present with symptoms and these cases when identified cannot then be considered as incidentalomas.

Criticism

The concept of the "incidentaloma" has been criticized, as such lesions do not have much in common other than the history of an incidental identification and the assumption that they are clinically inert. It has been proposed just to say that such lesions have been "incidentally found."[23] The underlying pathology shows no unifying histological concept.

References

- Lumbreras, B; Donat, L; Hernández-Aguado, I (1 April 2010). "Incidental findings in imaging diagnostic tests: a systematic review". The British Journal of Radiology. 83 (988): 276–289. doi:10.1259/bjr/98067945. ISSN 0007-1285. PMC 3473456. PMID 20335439.

- O'Sullivan, JW; Muntinga, T; Grigg, S; Ioannidis, JPA (18 June 2018). "Prevalence and outcomes of incidental imaging findings: Umbrella review". BMJ. 361: k2387. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2387. PMC 6283350. PMID 29914908.

- Cook DM (December 1997). "Adrenal mass". Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 26 (4): 829–52. doi:10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70284-x. PMID 9429862.

- "2009 AACE/AAES Guidelines, Adrenal incidentaloma" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Grumbach MM, Biller BM, Braunstein GD, et al. (2003). "Management of the clinically inapparent adrenal mass ("incidentaloma")". Ann. Intern. Med. 138 (5): 424–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00013. PMID 12614096. S2CID 23454526.

- Young WF (2007). "Clinical practice. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (6): 601–10. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp065470. PMID 17287480.

- Theo Falke and Robin Smithuis. "Adrenals - Differentiating benign from malignant". Radiology Assistant. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Cawood TJ, Hunt PJ, O'Shea D, Cole D, Soule S (October 2009). "Recommended evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas is costly, has high false-positive rates and confers a risk of fatal cancer that is similar to the risk of the adrenal lesion becoming malignant; time for a rethink?". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 161 (4): 513–27. doi:10.1530/EJE-09-0234. PMID 19439510.

- Hall WA, Luciano MG, Doppman JL, Patronas NJ, Oldfield EH (1994). "Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging in normal human volunteers: occult adenomas in the general population". Ann. Intern. Med. 120 (10): 817–20. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-120-10-199405150-00001. PMID 8154641. S2CID 23833253.

- Molitch ME (1997). "Pituitary incidentalomas". Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 26 (4): 725–40. doi:10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70279-6. PMID 9429857.

- Snyder (2021). "Causes, presentation, and evaluation of sellar masses".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Steele SR, Martin MJ, Mullenix PS, Azarow KS, Andersen CA (2005). "The significance of incidental thyroid abnormalities identified during carotid duplex ultrasonography". Archives of Surgery. 140 (10): 981–5. doi:10.1001/archsurg.140.10.981. PMID 16230549.

- Castro MR, Gharib H (2005). "Continuing controversies in the management of thyroid nodules". Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (11): 926–31. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-11-200506070-00011. PMID 15941700. S2CID 41308483.

- Shetty SK, Maher MM, Hahn PF, Halpern EF, Aquino SL (2006). "Significance of incidental thyroid lesions detected on CT: correlation among CT, sonography, and pathology". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 187 (5): 1349–56. doi:10.2214/AJR.05.0468. PMID 17056928.

- Papini E, Guglielmi R, Bianchini A, et al. (2002). "Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and color-Doppler features". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (5): 1941–6. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.5.8504. PMID 11994321.

- Jenny Hoang (5 November 2013). "Reporting of incidental thyroid nodules on CT and MRI". Radiopaedia., citing:

- Hoang, Jenny K.; Langer, Jill E.; Middleton, William D.; Wu, Carol C.; Hammers, Lynwood W.; Cronan, John J.; Tessler, Franklin N.; Grant, Edward G.; Berland, Lincoln L. (2015). "Managing Incidental Thyroid Nodules Detected on Imaging: White Paper of the ACR Incidental Thyroid Findings Committee". Journal of the American College of Radiology. 12 (2): 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2014.09.038. ISSN 1546-1440. PMID 25456025.

- Furtado CD, Aguirre DA, Sirlin CB, et al. (2005). "Whole-body CT screening: spectrum of findings and recommendations in 1192 patients". Radiology. 237 (2): 385–94. doi:10.1148/radiol.2372041741. PMID 16170016.

- Gould MK, Fletcher J, Iannettoni MD, et al. (2007). "Evaluation of Patients With Pulmonary Nodules: When Is It Lung Cancer?: ACCP Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (2nd Edition)". Chest. 132 (3_suppl): 108S–130S. doi:10.1378/chest.07-1353. PMID 17873164.

- Reddan DN, Raj GV, Polascik TJ (2001). "Management of small renal tumors: an overview". Am. J. Med. 110 (7): 558–62. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00650-7. PMID 11343669.

- Remzi M, Ozsoy M, Klingler HC, et al. (2006). "Are small renal tumors harmless? Analysis of histopathological features according to tumors 4 cm or less in diameter". J. Urol. 176 (3): 896–9. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.047. PMID 16890647.

- Content initially copied from: Hansen, Kristoffer; Nielsen, Michael; Ewertsen, Caroline (2015). "Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review". Diagnostics. 6 (1): 2. doi:10.3390/diagnostics6010002. ISSN 2075-4418. PMC 4808817. PMID 26838799. (CC-BY 4.0)

- Park HJ, Jeon YH, Rho MH, et al. (May 2011). "Incidental findings of the lumbar spine at MRI during herniated intervertebral disk disease evaluation". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 196 (5): 1151–5. doi:10.2214/AJR.10.5457. PMID 21512084.

- Mirilas P, Skandalakis JE (2002). "Benign anatomical mistakes: incidentaloma". The American Surgeon. 68 (11): 1026–8. PMID 12455801.